In the wake of the Black Sox scandal, in which players of the Chicago White Sox were accused of fixing the 1919 World Series, baseball was in need of a leader who could regain the public’s faith in the game.

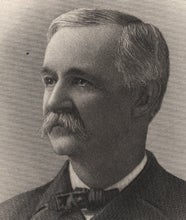

“We want a man as chairman who will rule with an iron hand,” said National League President John Heydler. “Baseball has lacked a hand like that for years. It needs it now worse than ever. Therefore, it is our object to appoint a big man to lead the new commission.”

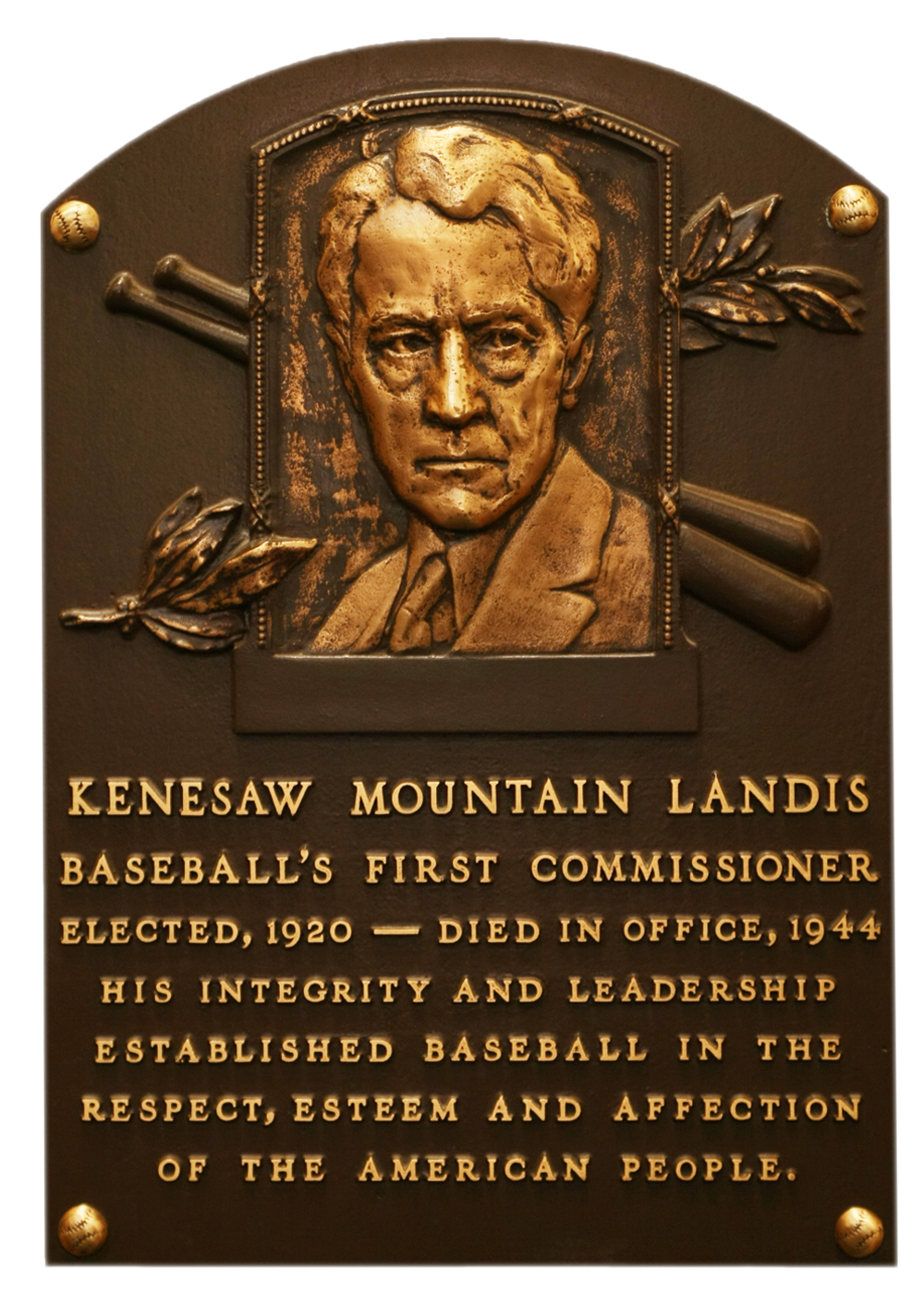

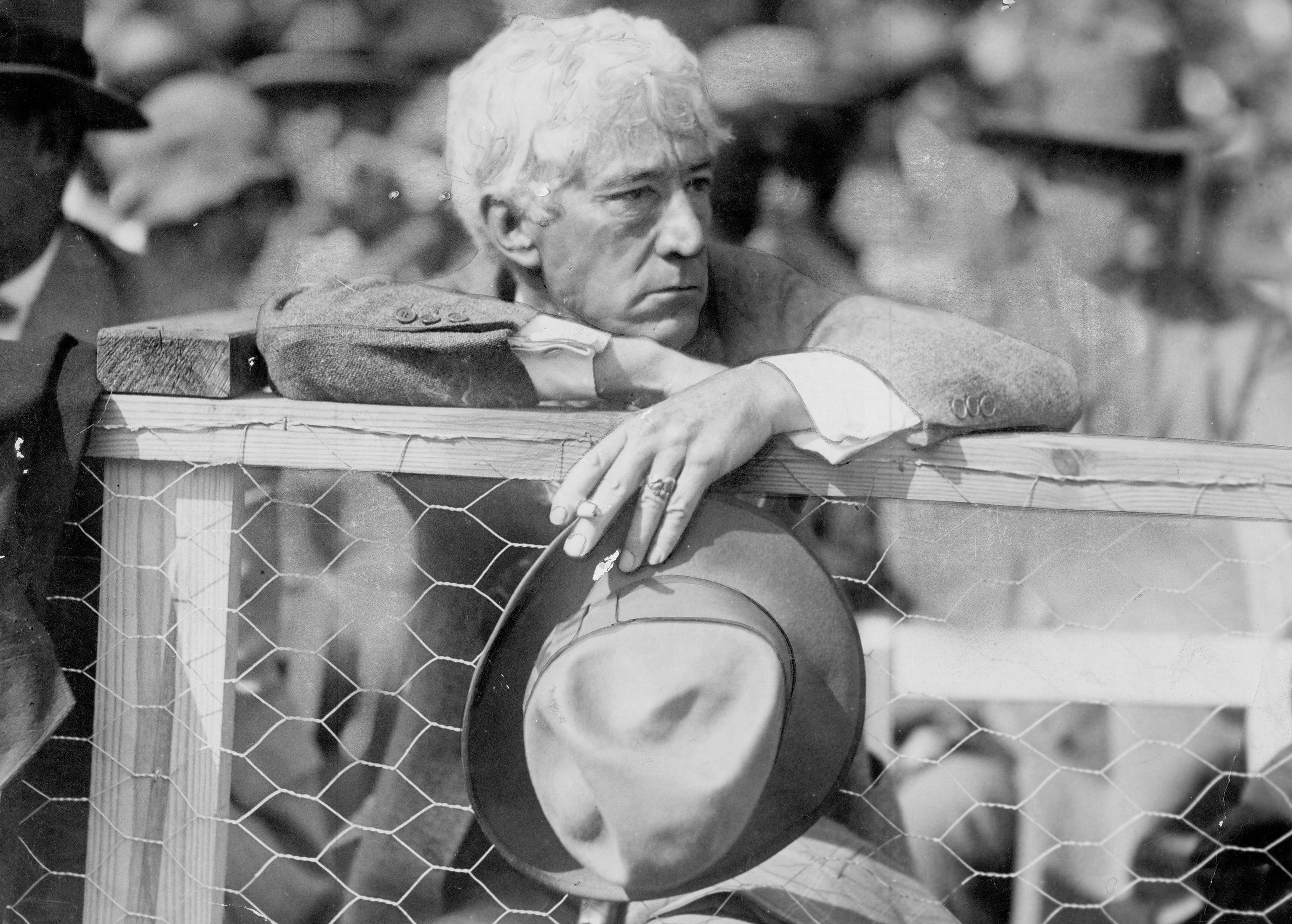

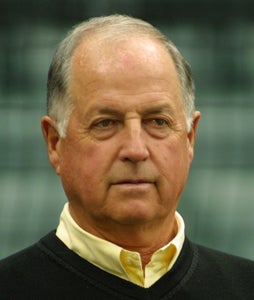

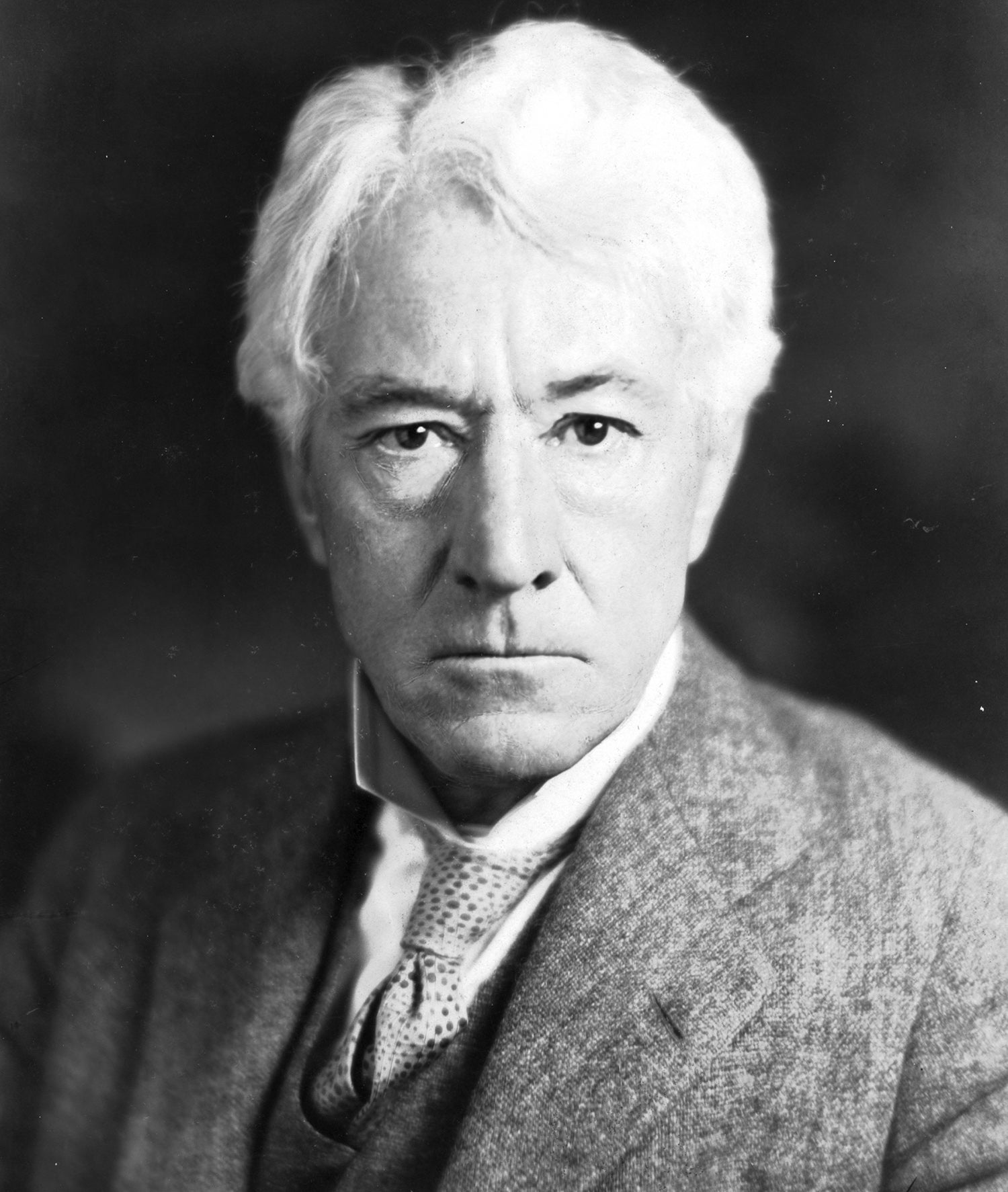

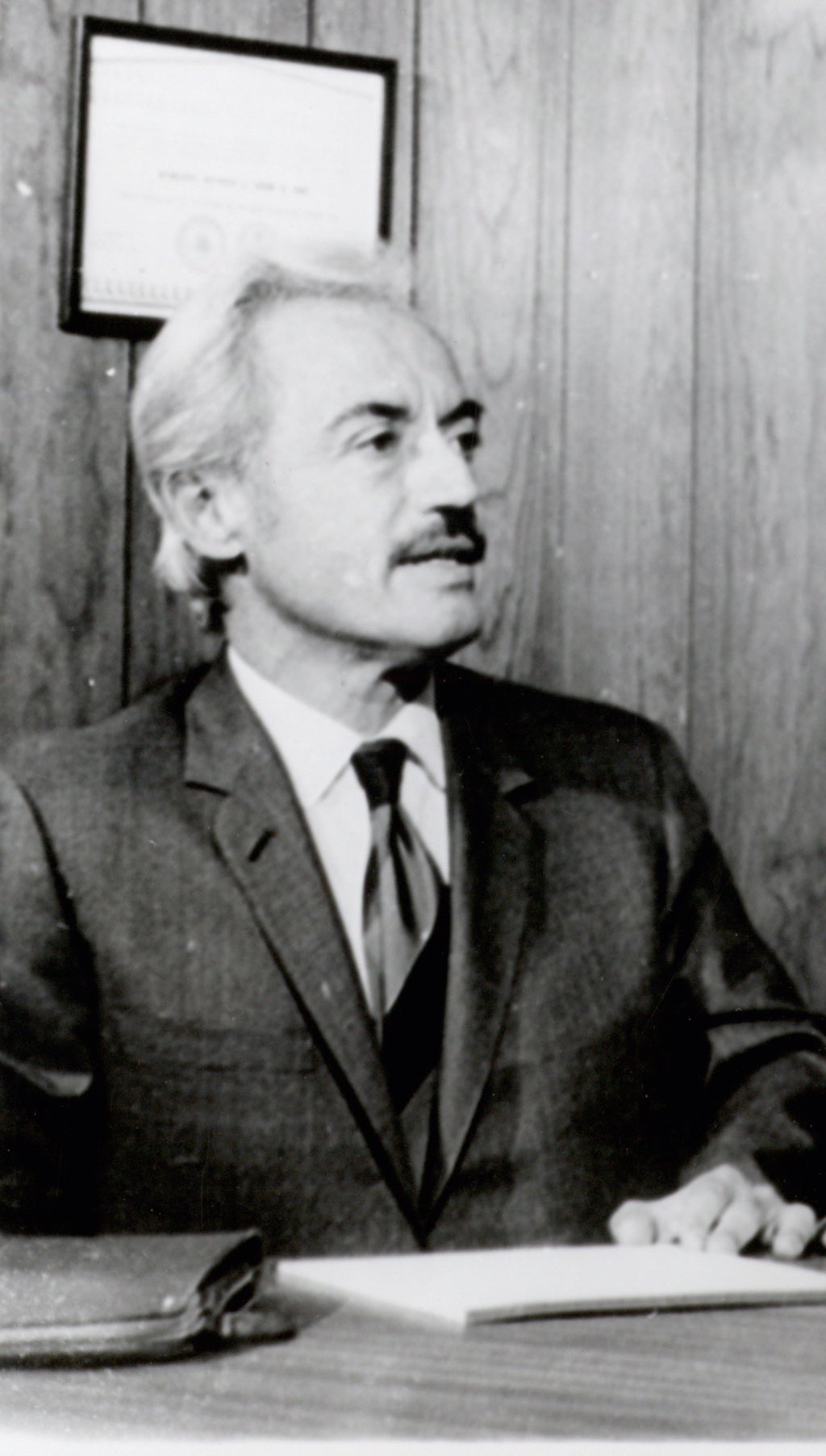

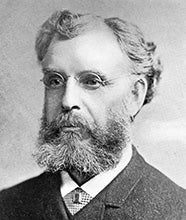

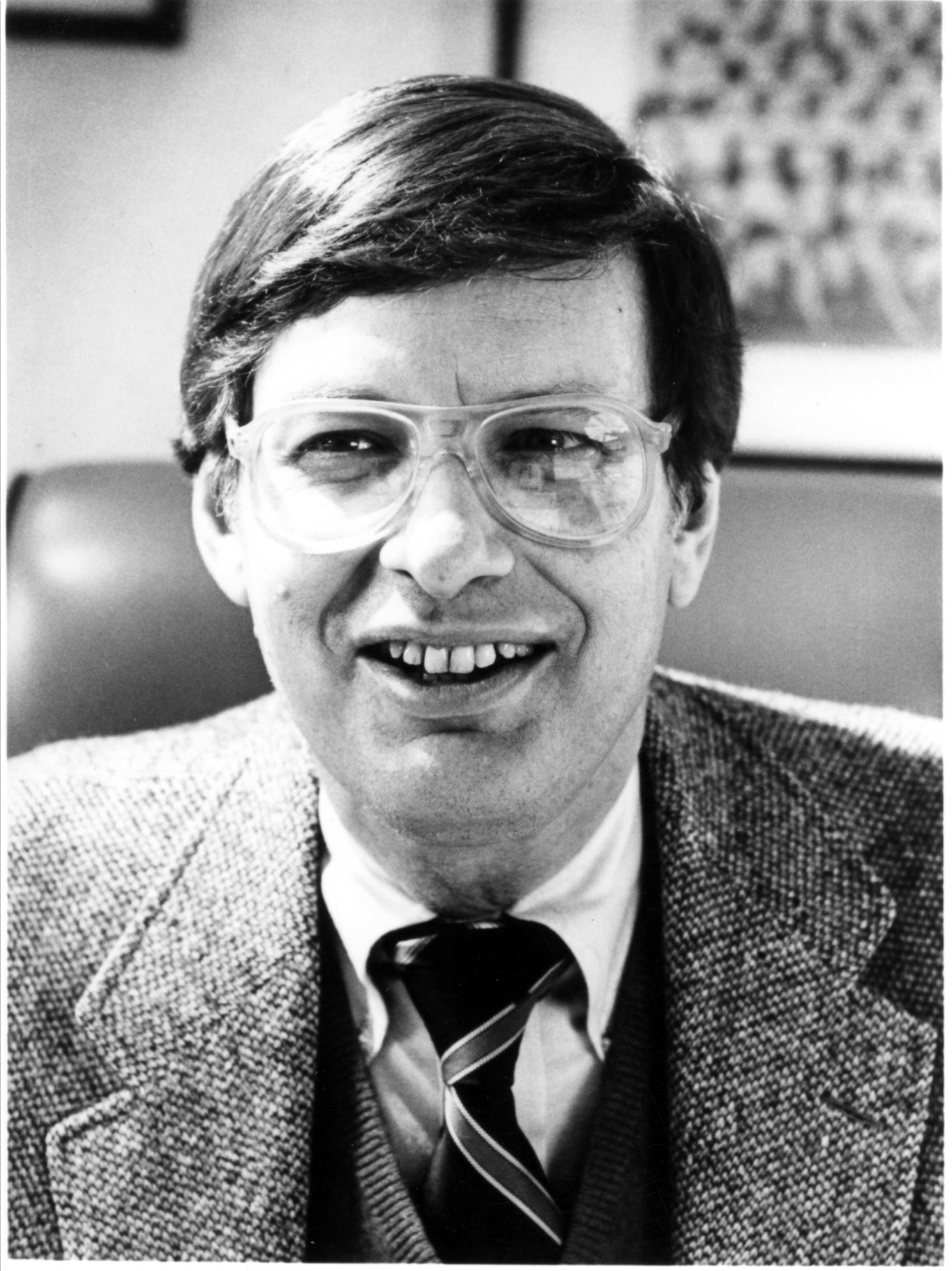

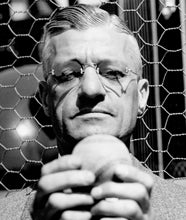

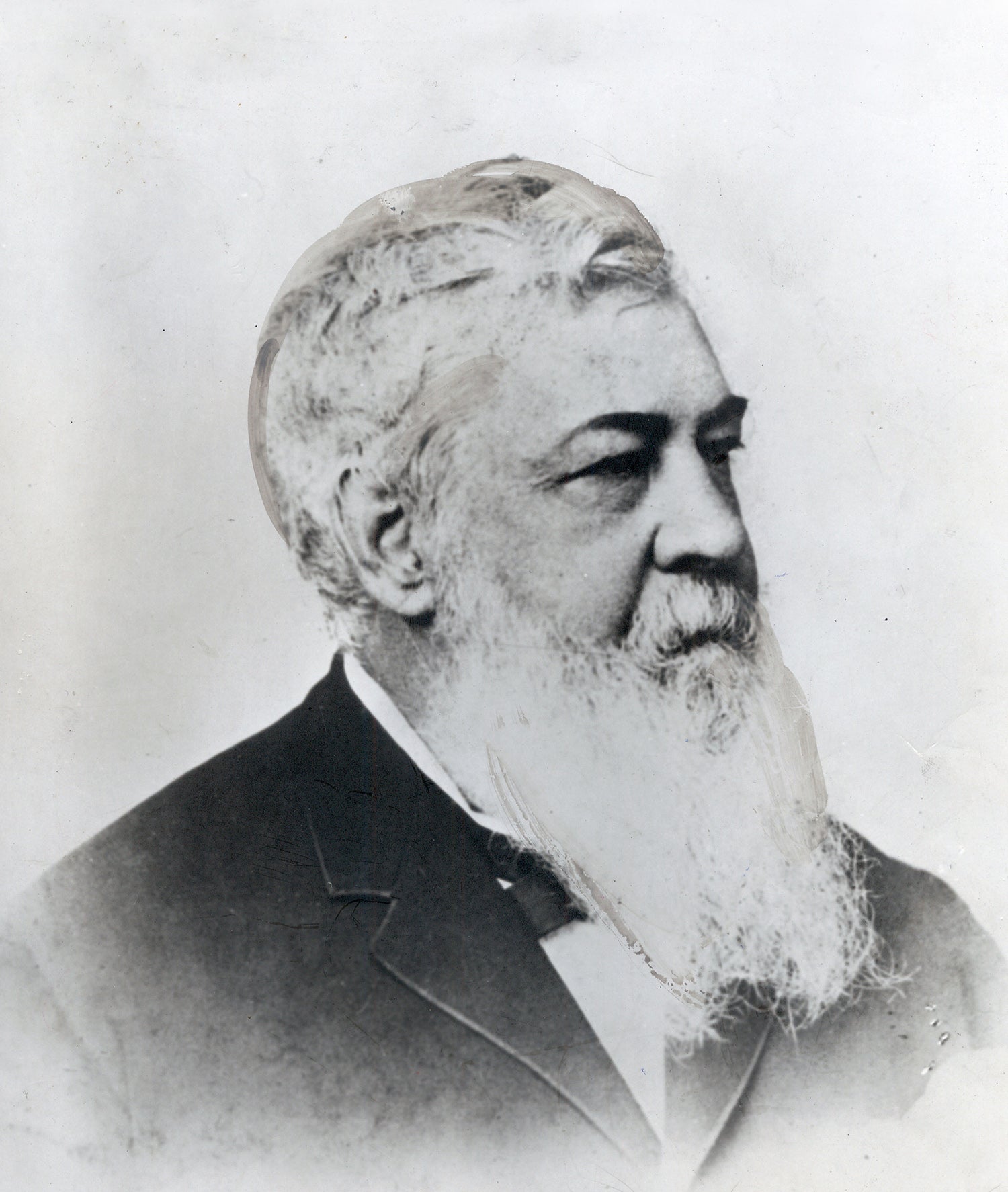

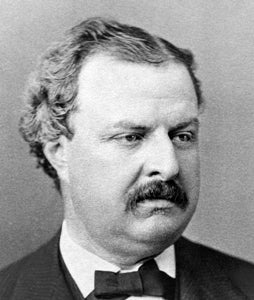

Heydler and his fellow executives got all that and more when they appointed baseball’s first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, in 1920.

Formerly a federal judge who had built a reputation for fighting corporations, Landis exercised his power as commissioner frequently and to the fullest extent, beginning with the Black Sox scandal. In his first major act as commissioner, Landis banned eight White Sox players from baseball for life for their involvement with New York gambler Arnold Rothstein – maintaining the ruling even after they were acquitted in a Chicago trial.

“Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player that entertains proposals or promises to throw a game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever again play professional baseball," Landis decreed.

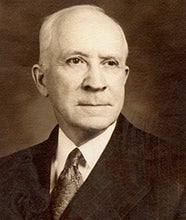

Over the next several years, Landis made it his foremost task to rid baseball of the crooks and gamblers who had crept into the game. He banned a total of 18 players, along with Phillies president William D. Cox, indefinitely for varying levels of involvement with gambling.

“Before 1920 if one player approached another player to throw a contest, there was a very good chance he would not be informed upon,” wrote Landis biographer David Pietrusza. “Now, there was an excellent chance he would be turned in.”

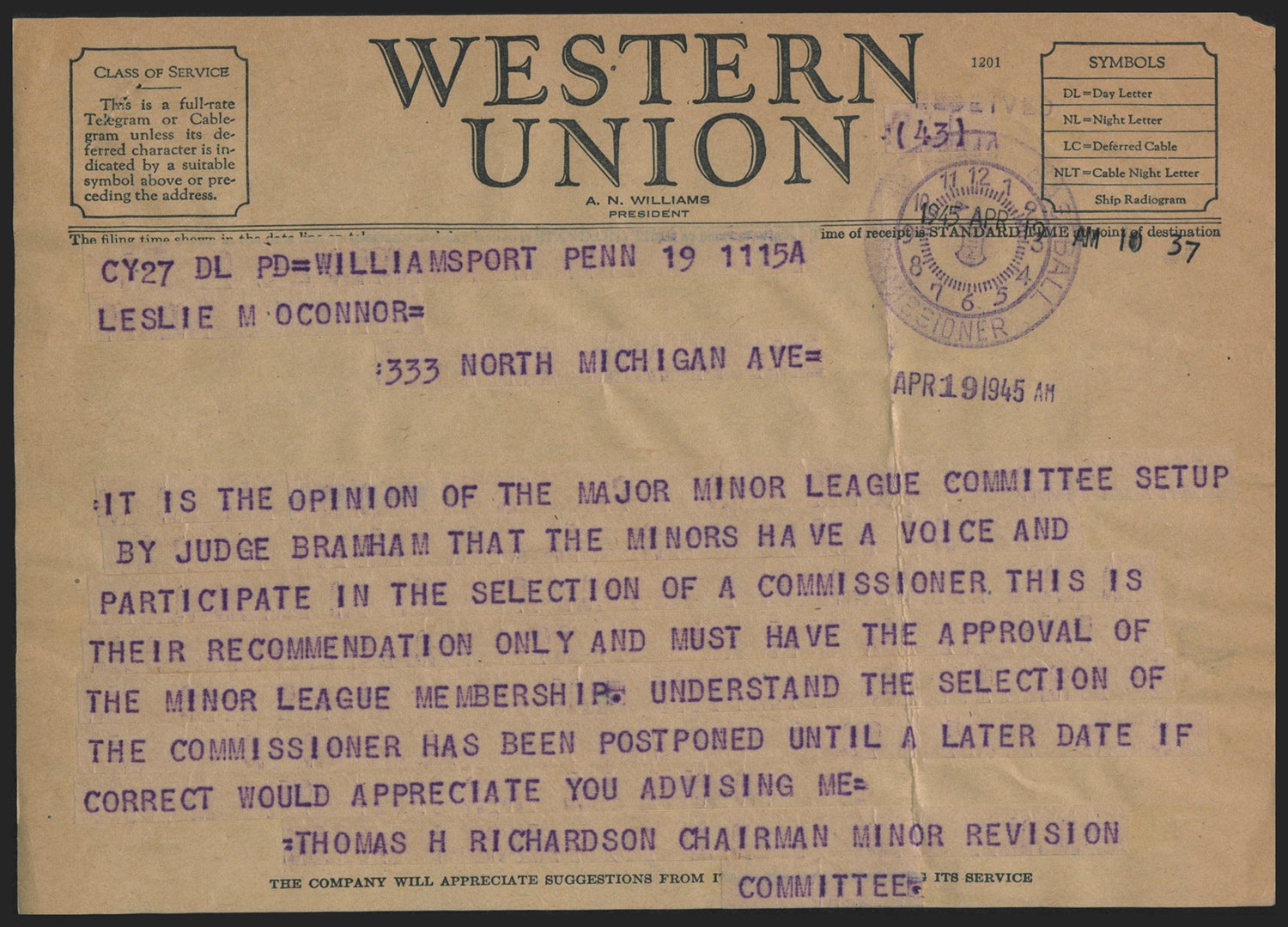

While Landis finished sweeping the bad seeds from the game, he turned his attention to opening up opportunities for up and coming players. Up until the 1920s, baseball’s minor leagues operated separately from the major leagues, and minor league players were not always allowed to move up. Landis demanded that all minor leagues become associated with the major league draft, and then subsequently demanded that major league clubs disclose all transactions within their farm systems. The new rule prevented teams from concealing prospects and ultimately denying them a path to the majors.

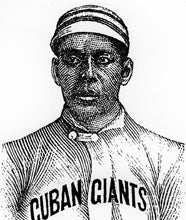

Despite his successes, Landis played a role in helping perpetuate a segregated game. He argued there were no rules preventing owners from signing Black players, stating, “Negroes are not barred from organized baseball by the commissioner…there is no rule in organized baseball prohibiting their participation and never has been to my knowledge.” Yet, he did nothing to encourage change, absolving himself of responsibility by stating that signing Black players was the business of club owners, while the commissioner’s job was to interpret and enforce the rules. As the most powerful person in baseball, Landis had the greatest ability to effect change, but his lack of overt action in promoting integration gave tacit approval to maintaining the status quo of a segregated system.

Though critics called him ruthless, there is no question that Landis' post-Black Sox scandal work restored dignity and respect to baseball. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in a special vote soon after his death on Nov. 25, 1944.