- Home

- Our Stories

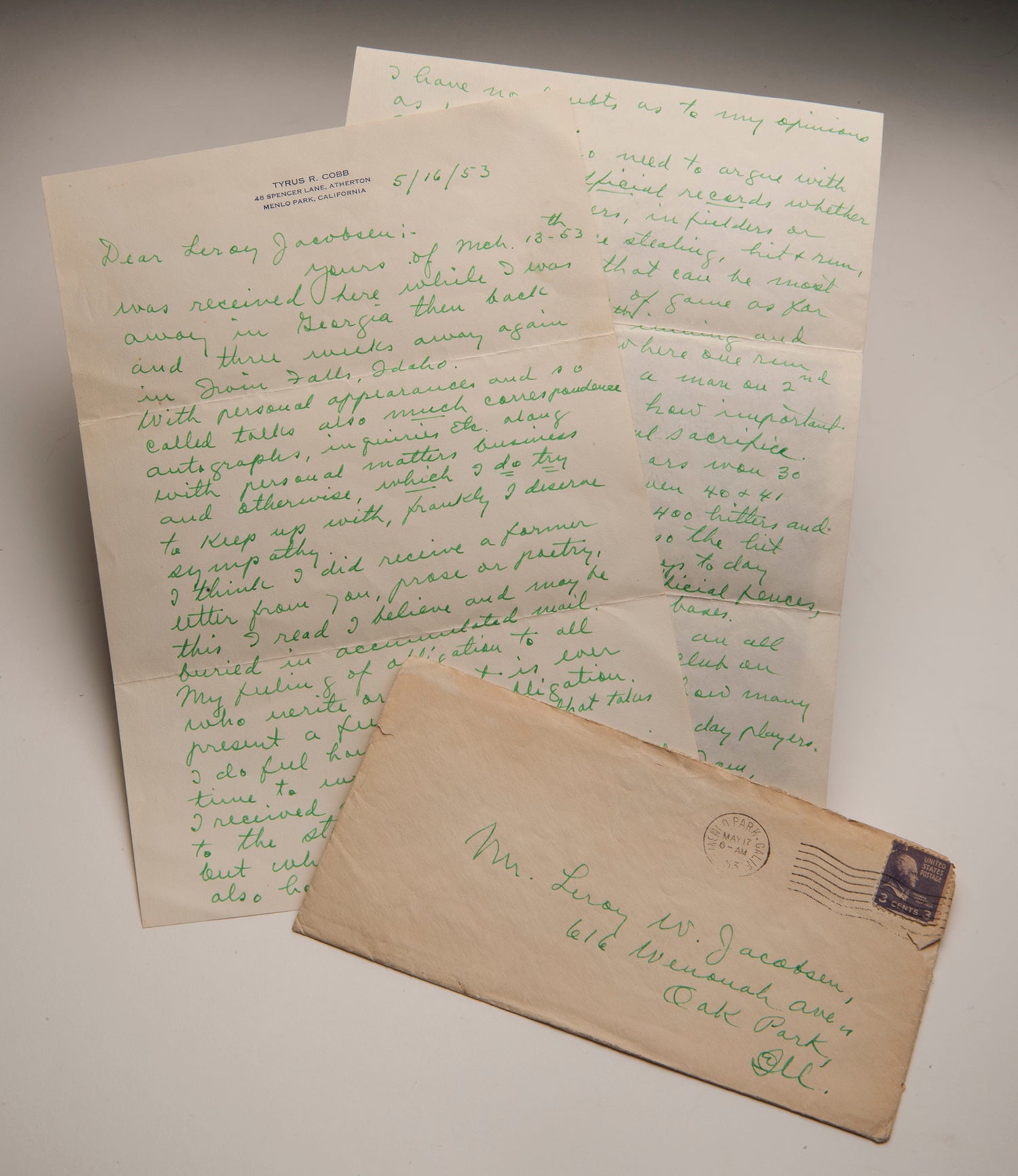

- Correspondence preserves timeline of search for Landis’ successor

Correspondence preserves timeline of search for Landis’ successor

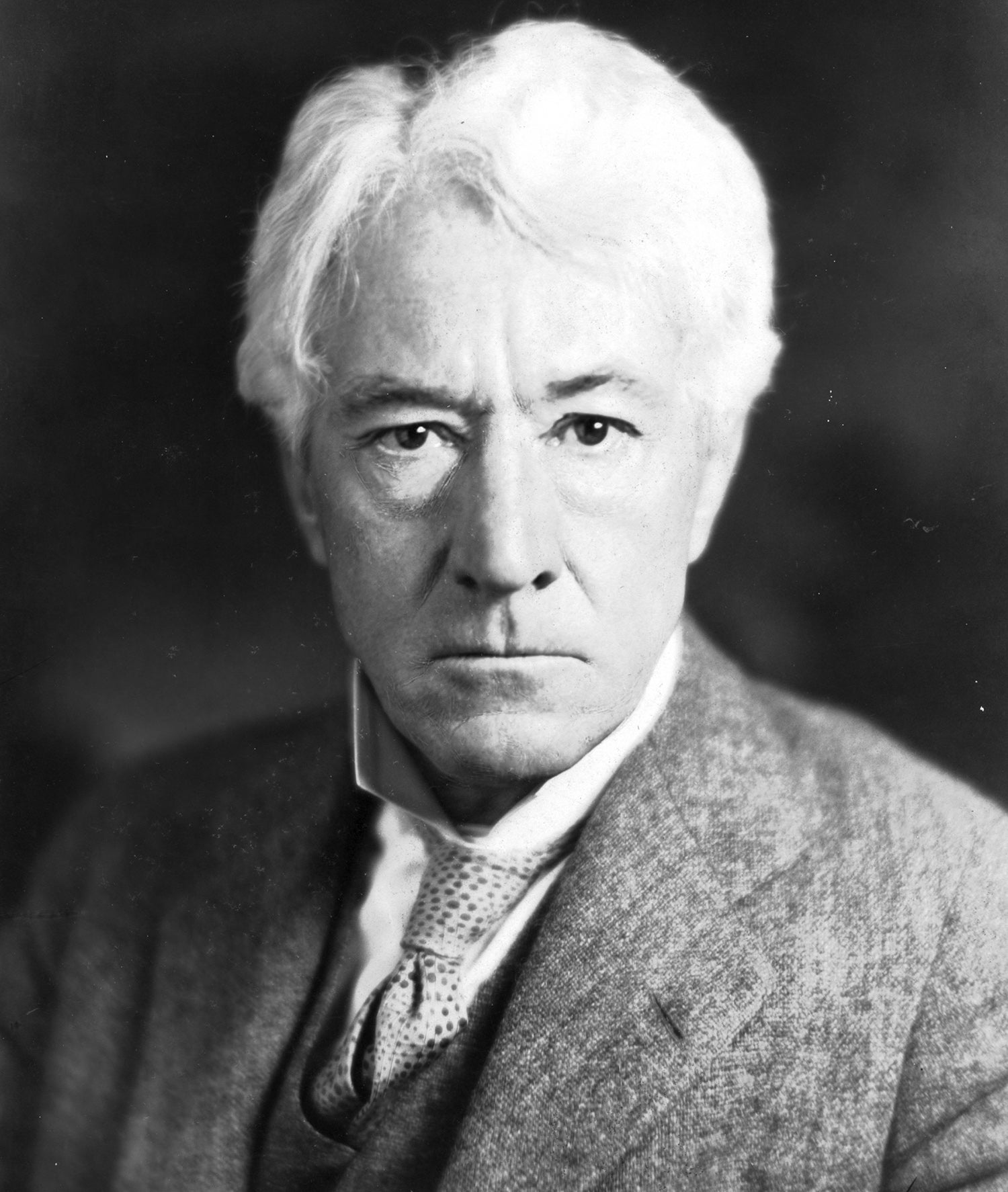

Named the first commissioner of baseball and given a mandate to clean up a game which had seen a spate of corrupt activity – most notably the Black Sox Scandal – Kenesaw Mountain Landis was the only head of the game many had ever known when he passed away on Nov. 25, 1944.

A little more than one week prior to his passing, he had been voted an additional seven-year term to serve as commissioner.

His tenure was a checkered one. While he received the “green light” to allow baseball to persist through World War II, removed known and alleged cheaters from the game and was a strong advocate for the All-Star Game (introduced in 1933), Landis is often criticized for his indifference toward admitting African Americans into organized baseball, essentially letting the owners maintain the status quo. Landis also – unsuccessfully – tried to quash the development of farm systems throughout baseball.

Yet, pros and cons aside, Landis was fondly remembered at his death, and his tenure as baseball commissioner would surely be tough act for anyone to follow.

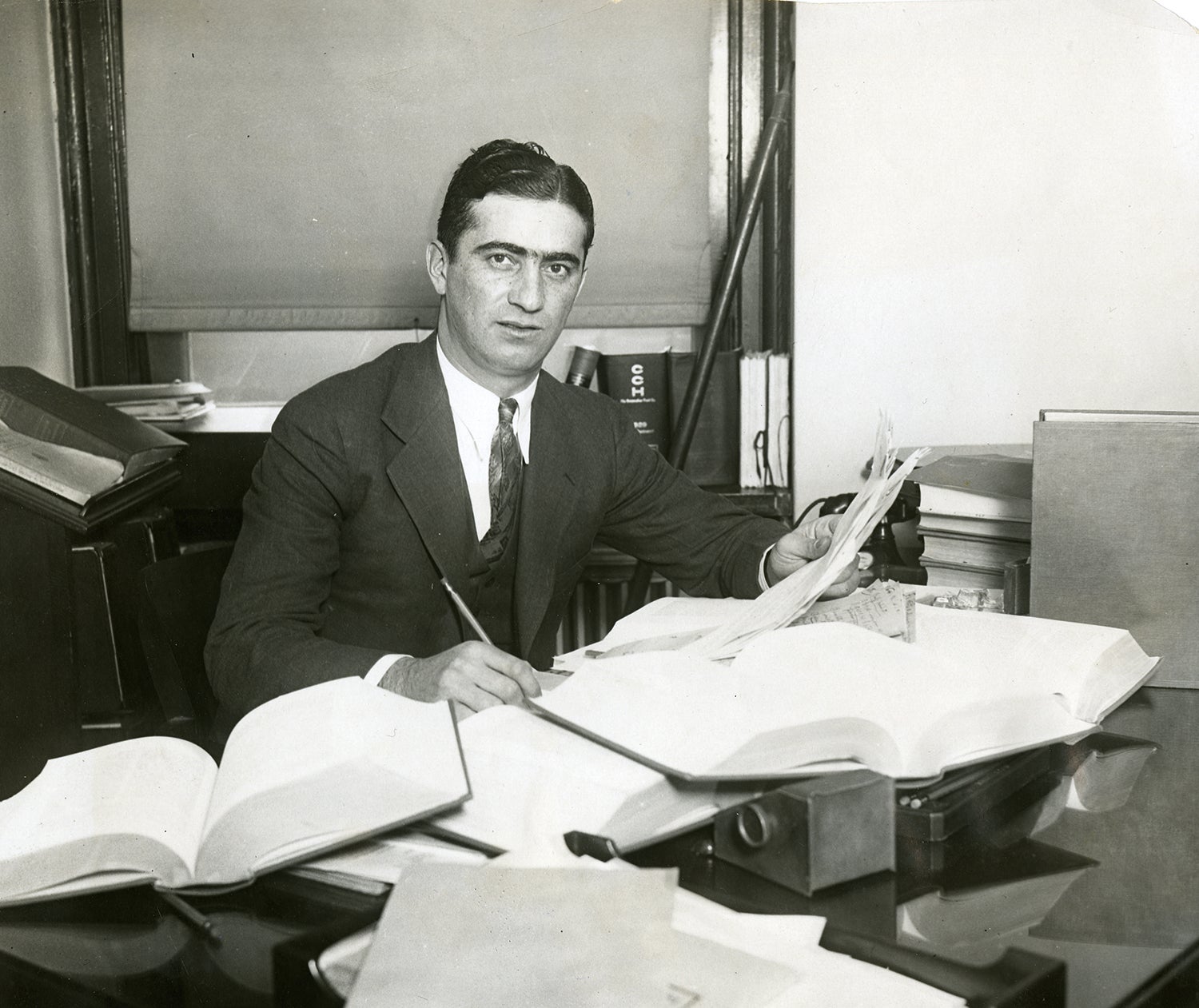

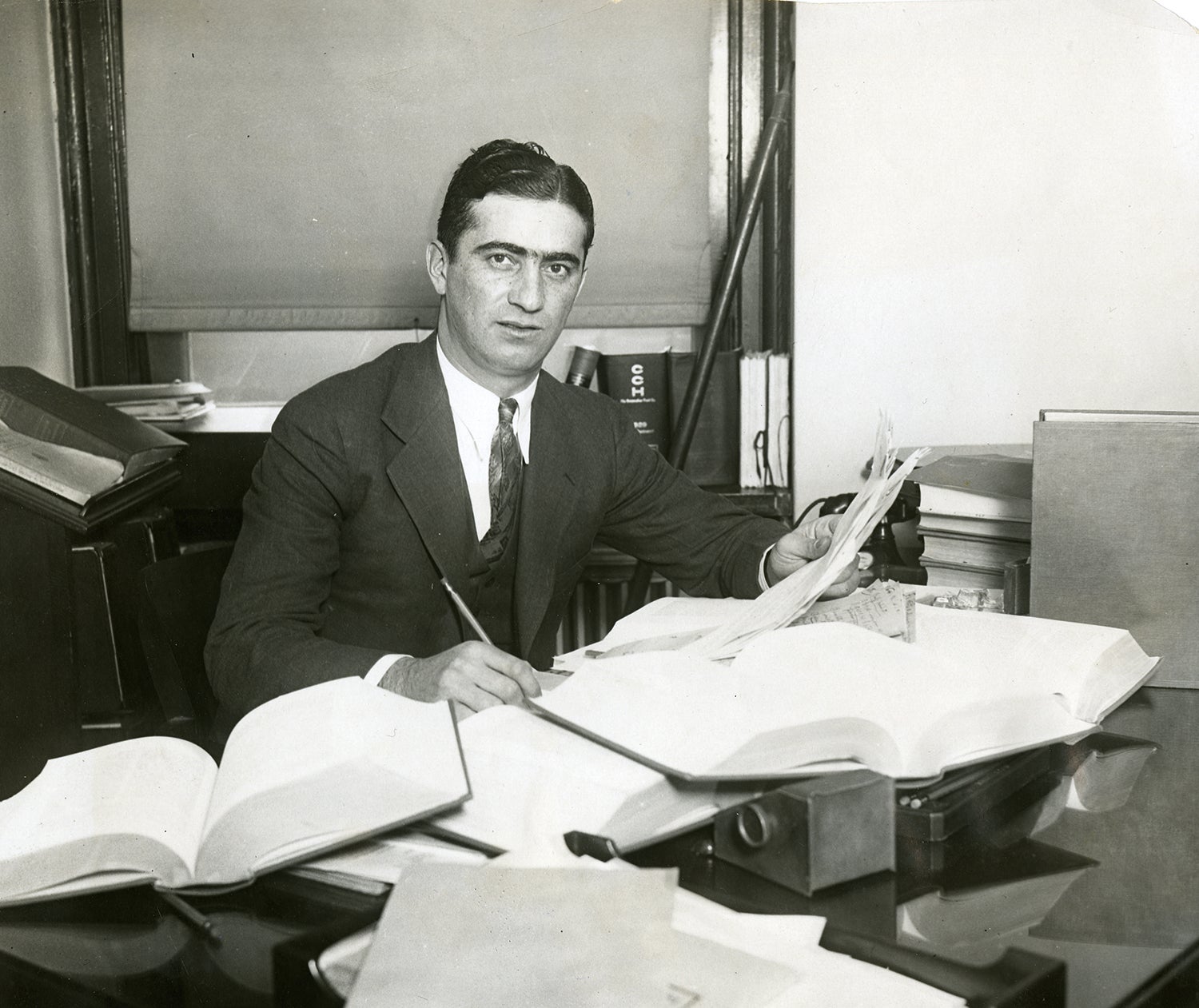

So it was that the task of locating a new commissioner would fall upon Leslie O’Connor. O’Connor had been Landis’ trusted assistant from 1921 through Landis’ passing, and it was his turn to become the torchbearer for baseball, albeit temporarily until such time when a new commissioner was appointed.

A recent acquisition of letters by the Baseball Hall of Fame Library shows that some individuals did not even wait until Landis had died to throw one’s hat in the ring for commissioner.

William F.E. Sullivan of New York was one such individual.

In a letter dated Oct. 18, 1944, a little more than a month before Landis died, Sullivan notes he read a newspaper article about Landis seeking his successor. Though he claims “a tremendous group of friends in the majors,” Sullivan maintains that he “never show[s] any partiality.”

In addition to his having owned a semi-professional baseball club, having been an umpire, and being a well-regarded businessman as credentials worthy of consideration, Sullivan also cites being a “world wide traveler,” living in or “traveling to every state in the union, and to all known parts of the globe” as reasons why Landis should choose him. Sullivan also insisted he would need one year to learn the ropes, or else he would refund his year’s salary.

There is no indication of Landis’ reaction to this piece of correspondence; he had recently been hospitalized in Chicago, forcing him to miss the World Series for the first time during his tenure as commissioner.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Within weeks of Landis’ death, the suggestions began arriving in O’Connor’s mailbox. On Dec. 13, 1944, Cleo W. Templeton, president of the Chicago-based American Brush Corporation, wrote to O’Connor, offering the name of Judge George E.Q. Johnson. Johnson had been nominated to become a federal judge but is best known as the U.S. Attorney who won a conviction on Al Capone for tax evasion.

Frank Quinn, executive secretary and director of the Texas State Parks Board, had another jurist in mind. He nominated John Donelson Martin, Sr., a member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Judge Martin offered more baseball experience than Judge Johnson, as he had served as president of the minor league Southern Association from 1919 into 1938. Quinn thought he was “doing each of you and baseball in general a great favor” by suggesting Martin for the post.

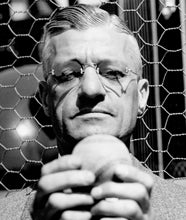

The directors of the Pacific Coast League also offered one of their own in Clarence “Pants” Rowland. In a telegram sent to O’Connor, who then forwarded the message to league presidents William Harridge and Ford Frick, the PCL directors nominated Rowland, whom they deemed “thoroughly conversant with baseball from every angle … and familiar with baseball problems from coast to coast.”

Rowland, who had little professional playing experience, made his mark as a minor league manager before being tapped by Charlie Comiskey as the Chicago White Sox’s pilot for 1915. He led the club to a World Series title in 1917 but was fired after a sixth-place finish the next season. After working for the Chicago Cubs, Rowland found a home with Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League, being named the top minor league executive by the Sporting News in 1943. He was the loop’s president when the PCL directors offered his name for consideration. Not chosen for commissioner, Rowland remained with the PCL through the 1954 season before returning to the Cubs, where he stayed until his death in 1969.

Another submission, from Harold Koch, a furniture store manager in Indianapolis, was for that of Harry Geisel. Geisel had not long before retired from an 18-year career as an umpire for the American League. He had spent several seasons as a minor league arbiter before reaching the big leagues. Also not picked to succeed Landis, Geisel would instead become athletic director for the Indiana Boys School.

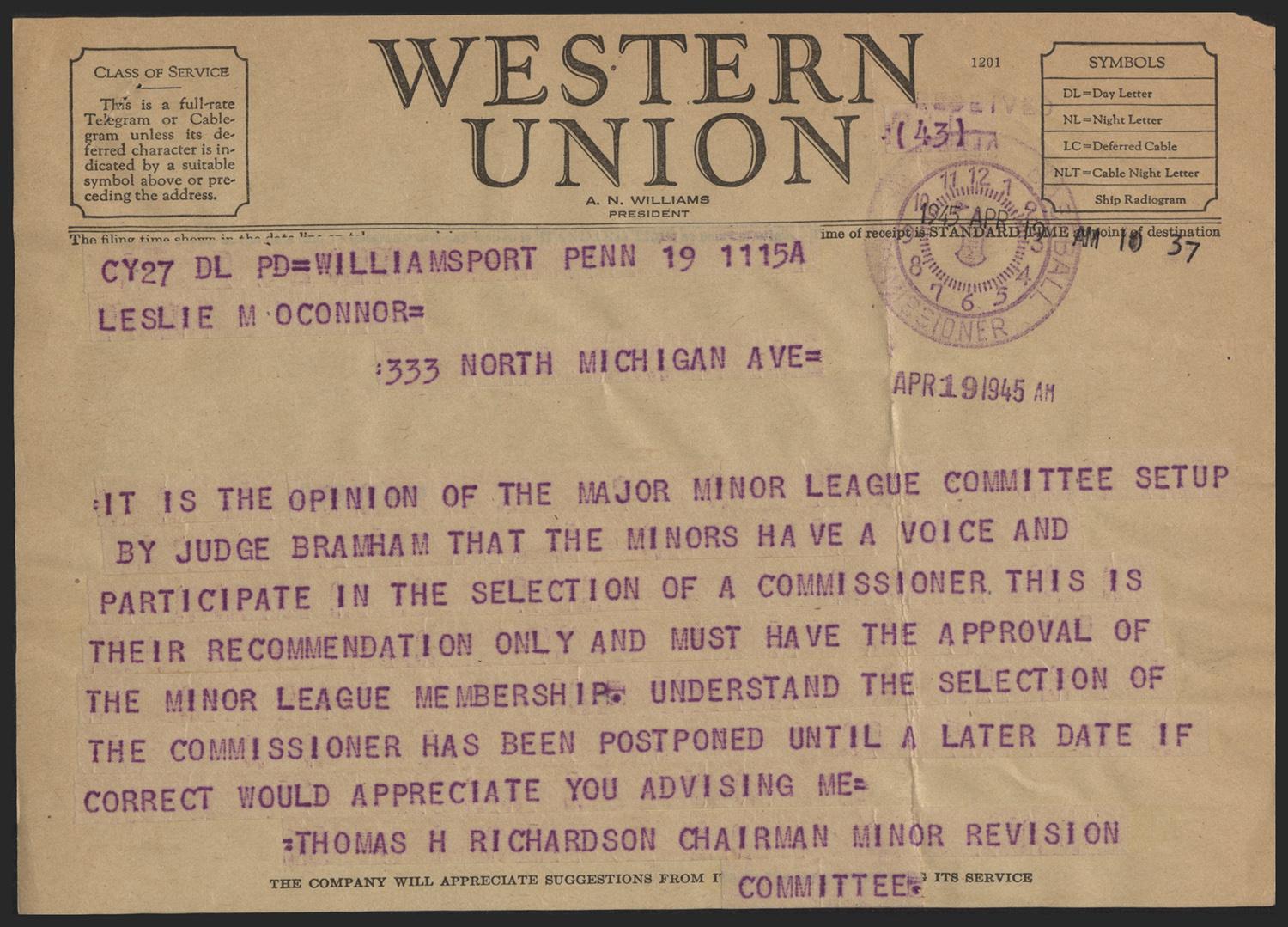

This Western Union telegram, dated April 19, 1945, is from Thomas H. Richardson to Kenesaw Mountain Landis' assistant, Leslie O'Connor. In it, Richardson advocates for an increase in participation by the minor leagues in selecting the next Commissioner of Baseball. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Though many individuals from across the country offered their picks for the next commissioner, the chairman from the minor league revision committee, Thomas Richardson, reached out to O’Connor to make sure that they had a role in the selection process. O’Connor assured him that the proposed meeting on April 24 was still in place.

James Delay, a municipal court judge from Roxbury, Mass., apparently reached out to O’Connor seeking a different position. Delay offered his life summary and said being “Assistant Commissioner of Baseball” is something he has “often dreamed of … and how much [he] would like to hold it.”

Perhaps shattering his dreams, O’Connor told Delay “there is no office of ‘Assistant Commissioner of Baseball’ and there never has been any suggestion of the establishment of such an office.” O’Connor goes on to tell Delay to reach out to Frick and Harridge should he wish to apply for commissioner.

Such a response encouraged someone to remark “Good old courteous Leslie!!!” on the letter.

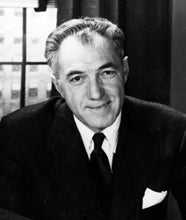

On April 24, 1945, when baseball’s owners convened in Cleveland to pick the new commissioner, none of the above submissions fell under consideration. After much discussion, the commissioner’s job ultimately went to Albert “Happy” Chandler, a U.S. Senator from – and former governor of – Kentucky. Chandler delayed his start as commissioner in order to remain in the Senate until he had the opportunity to cast votes on important legislation.

Though his term as commissioner expired in 1952, Chandler sought and failed to receive contract extensions in 1950 and 1951. He later chose to resign, effective July 15, 1951.

Matt Rothenberg was the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#Shortstops: Jimmy Dugan had it all wrong

#Shortstops: Moe Berg’s life in baseball

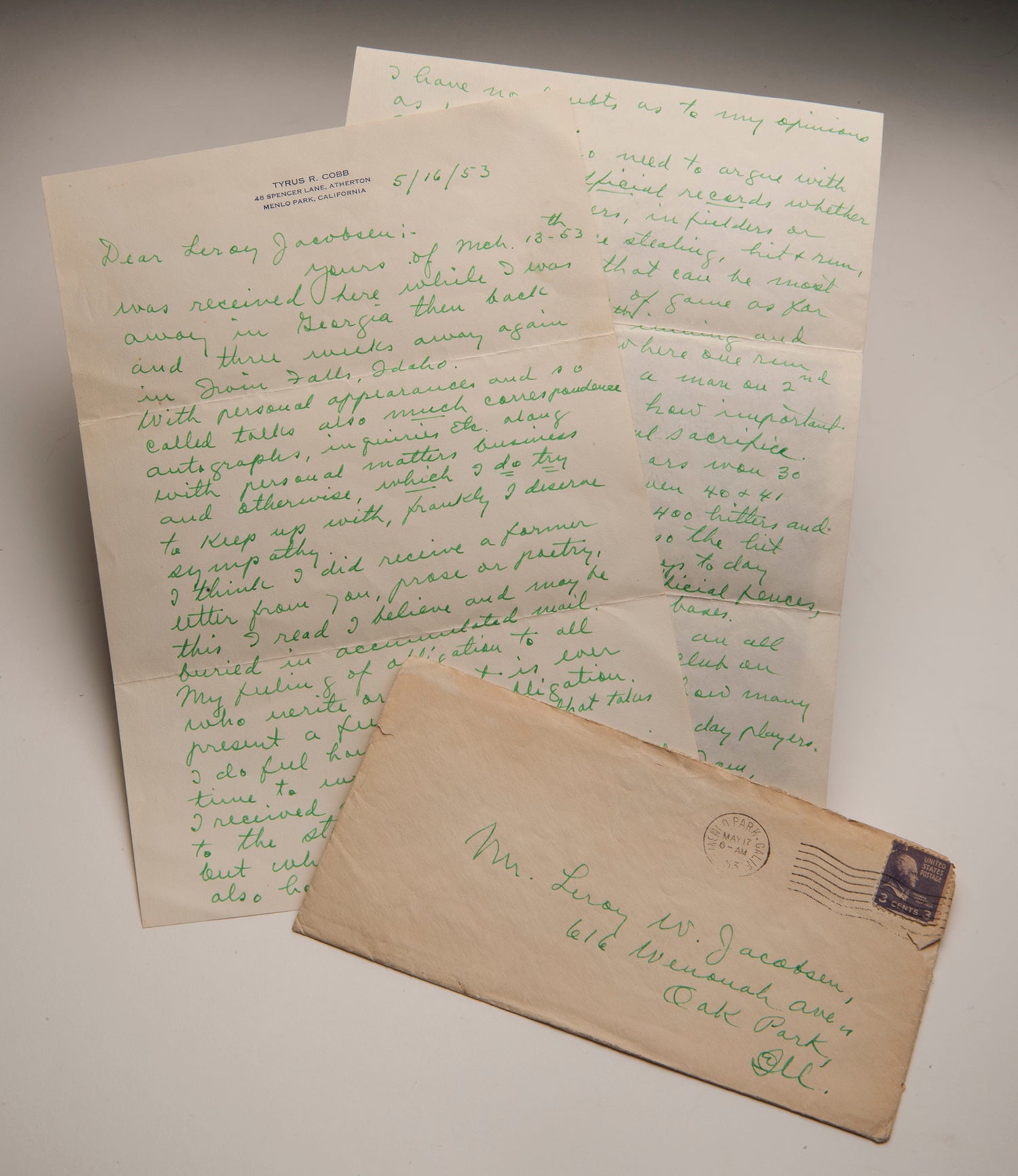

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

#Shortstops: Jimmy Dugan had it all wrong

#Shortstops: Moe Berg’s life in baseball