- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Moe Berg’s life in baseball

#Shortstops: Moe Berg’s life in baseball

While a recent beer advertising campaign may have co-opted the phrase “the most interesting man in the world,” the moniker certainly could have applied to longtime big league catcher Moe Berg.

Berg was a journeyman backstop for 15 seasons, ending his playing career in 1939 after stints with the Brooklyn Robins, Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox.

But what made this native of Newark, N.J. unique was his off-the-field endeavors, such as being Ivy League educated, understanding multiple languages, a voracious appetite for reading multiple newspapers every day, earning a law degree during his playing days, and his performance as a decorated spy during World War II. There was even talk of George Clooney portraying him in a movie.

The learned linguist signed with Brooklyn as an infielder after graduating from Princeton University magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages in 1923, turning down more prestigious offers in academia and business.

Moe Berg signed with the Brooklyn Robins as an infielder after graduating from Princeton University magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages in 1923, turning down more prestigious offers in academia and business. “I would rather be a ballplayer than a bank president or a judge,” Berg would explain. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

“I would rather be a ballplayer than a bank president or a judge,” Berg would explain.

Berg’s first big league season in 1923 was spent mainly as a shortstop before injuries in 1927 forced him to transition into a catcher, a position he remained at for the rest of his career.

“Moe Berg was as smart a ballplayer as ever come along,” said Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel. “Knew the legs wouldn’t cooperate in the infield and when the catching job opened he grabs a mask and puts it on and there he was. Guy never caught in his life and then goes behind the plate like Mickey Cochrane. Now that’s somethin’. But, I’ll tell ya again, nobody ever knew his life’s history. I call him the mystery catcher. Strangest fellah who ever put on a uniform.”

Berg spent the winter after his first pro season taking classes at the Sorbonne in Paris, then later attended Columbia University law school during his off-seasons, graduating with a law degree in 1928 and earning admission to the New York Bar Association later that year.

The acclaimed athlete-scholar’s best season came in 1929 when he caught 106 games for the White Sox and batted .287, but spent most of his career as a well-respected backup. His lifetime batting average was .243 and he hit a mere six home runs.

Buck Crouse, a former White Sox teammate and fellow catcher, once gently chided his friend: “Moe, I don’t care how many of them college degrees you got. They ain’t learned you to hit that curveball no better than me.”

“Yeah, I know, and he can’t hit in any of them” teammate Dave “Sheriff” Harris once famously remarked after being informed that Berg spoke seven languages.

Erudite and witty, Berg was philosophical when it came to his place in the game.

“I have met many men in the major league who excel over me in ways that I envy,” Berg once said. “Because I speak a few languages does not place my abilities over theirs. The joy of baseball is that a man must stand on his two feet and face his opponents. Philology (language knowledge) cannot assist me in fielding a grounder flawlessly or help when I’m at the plate, the bases are loaded, and my team is behind.”

Though more noted for his headwork than his footwork, the 6-foot-1 and powerfully built Berg was a slow runner but considered a fine catcher with a strong arm who had the ability to handle pitchers. In fact, he set an American League record by catching in 117 consecutive games, from 1931 to 1934, without making an error (a record that would last 12 years).

Today, a Spalding catcher's mask belonging to Berg that he used in the 1930s is part of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s permanent collection.

“Moe was really something in the bullpen,” said a former teammate. “We’d all sit around and listen to him discuss the Greeks, the Romans, the Japanese, anything. Hell, we didn’t know what he was talking about, but it sure sounded good.”

One of Berg’s former managers explained Berg’s important role this way: “He’s just as necessary to our team as if he were out there catching 154 games. Don’t forget that when he’s not behind the plate he’s in the bullpen schooling those young pitchers for relief work. He steadies the young pitchers and catchers and peps up the vets.”

Berg proved his fine intellect to a national audience when he appeared a number of times on the popular radio program “Information Please.”

“Moe Berg,” said John Kieran, a New York Times sports columnist and fellow panelist on “Information Please,” “is the smartest fellow I’ve ever met.”

Proving himself a talented writer, baseball’s foremost man of letters penned a highly regarded piece for the September 1941 issue of Atlantic Monthly entitled “Pitchers and Catchers.”

“The catcher works in harmony with the pitcher and dovetails his own judgment with the pitcher’s stuff,” wrote Berg, in an excerpt from his piece. “He finds out quickly the pitcher’s best ball and calls for it in the spots where it would be most effective. He knows whether a hitter is in a slump or dangerous enough to walk intentionally. He tries to keep the pitcher ahead of the hitter. If he succeeds, the pitcher is in a more advantageous position to work on the hitter with his assortment of pitches. “But if the pitcher is in a hole – a two and nothing, three and one, or three and two count – he knows that the hitter is ready to hit. The next pitch may decide the ballgame. The pitcher tries not to pitch a ‘cripple’ – that is, tries not to give the hitter the ball he hits best. “Taking the physical as well as the psychological factors into consideration, the pitcher must at times give even the best hitter his best pitch under the circumstances. He pitches hard, lets the law of averages do its work, and never second-guesses himself. The pitcher throws a fastball through the heart of the plate, and the hitter, surprised, may even take it. The obvious pitch may be the most strategic one.”

After a few seasons as a coach with the Red Sox, newspapers across the country in January 1942 shared the news that Berg would be leaving the team in order to accept a government job as a goodwill ambassador with Nelson Rockefeller, the coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, in Central and South America where his ability to speak Spanish and Portuguese could be utilized best.

It was in this newfound role that Berg made a radio plea to the Japanese people in their own language on Feb. 23, 1942, 11 weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, warning them that they had been betrayed by their leaders. Berg had become fluent in the Japanese language during baseball trips to the country in 1932 and 1934.

“You have outraged us and every other nation in the world with the exception of two – two that are tainted with blood – Germany and Italy – they welcome you as friends. But your temporary victories will bring you only misery,” Berg pleaded. “You cannot win this war. We and the 20 other republics of America are unified – we are united. Your leaders have betrayed you.

“After the war, a nation will have to be watched to prove its right to be partners among the civilized. We were patient and took much abuse. We humbly made many concessions – we tried to remain friends. Believe me when I tell you that you cannot win this war. I am speaking to you as a friend of the Japanese people, and tell you to take the reins now. Your warlords are not telling you the truth. The people of the United States and the people of Japan can be friends as they were in the past. It is up to you.”

By August 1943, Berg was recruited to join the Office of Strategic Services – the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency – as an undercover agent. Stationed in Europe, he was tasked with, among other responsibilities, trying to determine Germany’s development of an atomic bomb.

“Moe was absolutely ideal for undercover work. Not by design; just by nature,” said Michael Burke, a fellow OSS agent and later owner of the Yankees. “One, because of his physical attributes. He could go anyplace without fear. He had stamina. Also, he had a gift for languages. In addition, he had an alert, quick mind that could adapt itself into any new or strange subject and make him comfortable quickly.

“He was immensely involved intellectually and active in international affairs through reading and travel. He had the capacity to be at home in Italy or France or London or Bucharest. He was on familiar ground in all those places,” Burke added. “He also possessed a great capacity for being able to live comfortably alone, and could do this for a long period of time. The life of an agent sometimes is a lonely one and some people aren’t suited for that.”

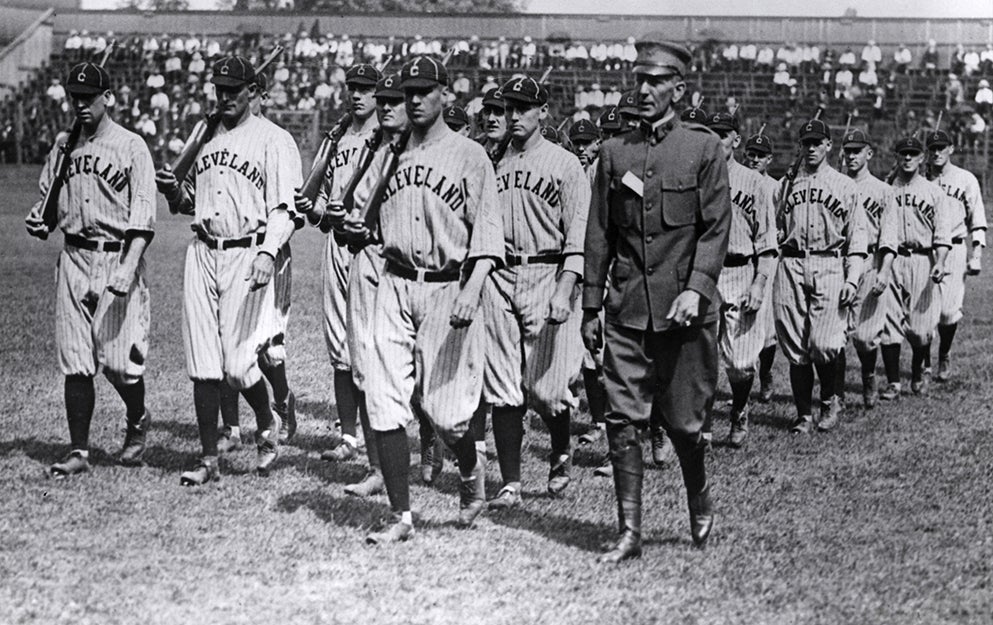

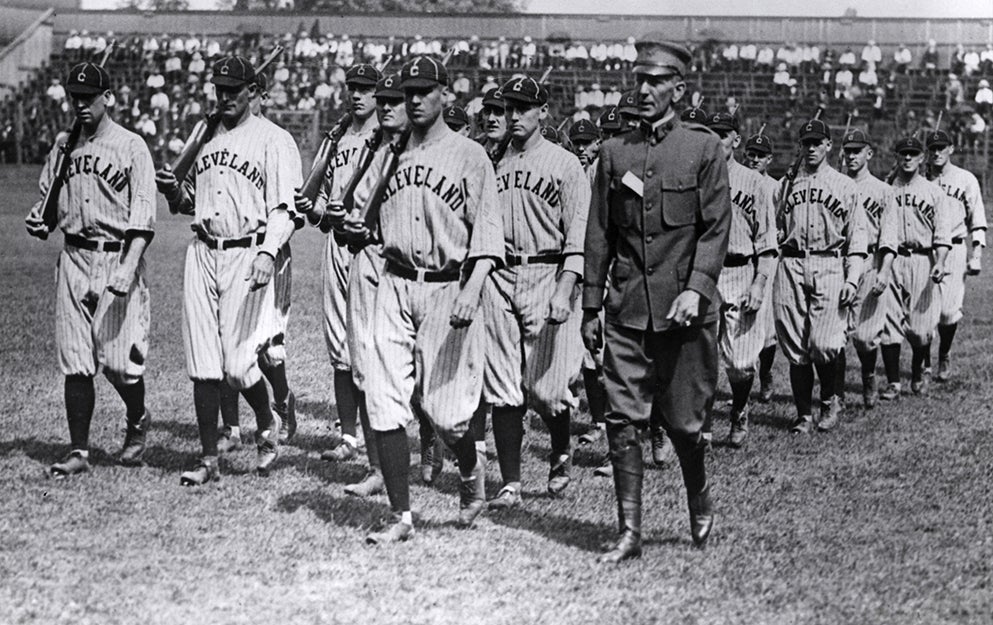

While serving under Nelson Rockefeller as a goodwill ambassador, Moe Berg made a radio plea to the Japanese people in their own language on Feb. 23, 1942, 11 weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, warning them that they had been betrayed by their leaders. He had become fluent in Japanese during baseball trips to the country in 1932 and 1934. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Berg would later be awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given to civilians during wartime, but he refused it. After he died, his sister, Ethel, claimed the award, which she later donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame. “Mr. Morris Berg, United States Civilian, rendered exceptionally meritorious service of high value to the war effort from April 1944 to January 1946,” reads the Medal of Freedom citation. “In a position of responsibility in the European Theater, he exhibited analytical abilities and a keen planning mind. He inspired both respect and constant high level of endeavor on the part of his subordinates which enabled his section to produce studies and analysis vital to the mounting of American operations.” After WWII, Berg spent his last few decades seemingly adrift, his life revolving around reading and baseball. Minutes before he died at the age of 70 on May 29, 1972, he reportedly turned to a nurse and spoke his last words: “How did the Mets do today?” It was a few years later that Dr. Samuel Berg began corresponding with the Baseball Hall of Fame about possibly donating artifacts from his brother Moe’s career. In a letter dated Oct. 26, 1977, Dr. Berg wrote to Hall of Fame Director Howard Talbot: “Approaching what is considered old age, I must expect the inevitable. Before that time, I plan on disposing of my possessions in the most favorable way. Among these are personal items used by my brother when playing under the name of Moe Berg. He never attained Hall of Fame stature, but he certainly attained eminence that casts credit on the game he played over a period of 17 years. When a motion picture of his activities on and off the diamond is made, which is inevitable, the game of baseball will gain very favorable publicity.” Dr. Berg, who passed away in 1990 at the age of 92, proved prophetic, as it was announced in April 2016 that actor Paul Rudd is set to star in The Catcher Was a Spy, based on the 1994 Berg biography written by Nicholas Dawidoff. Clooney was attached to the starring role in different studio’s incarnation years earlier. Talbot would later respond to Dr. Berg on July 13, 1978, thanking him for a number of donations, which included: A uniform from the 1934 Japan baseball tour; a Senators jersey, pants and cap; two Brooklyn caps; one White Sox cap; one catcher’s mask; one cup protector; one ceramic ashtray from the 1934 Japan baseball tour; one Moe Berg signature bat. “In my prejudiced opinion, Moe has not been appreciated enough by the baseball fraternity,” Dr. Berg wrote in a final missive to Talbot on July 26, 1978. “You should know that Judge Landis remarked, after Moe appeared three times on ‘Information Please’ and a few years after the Black Sox scandal, ‘Moe, you have done more to restore the good name of baseball than any other player,’ or words to that effect.”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Hall of Fame Veterans

Hall to Honor Curt Flood’s Legacy, World War II Players during Awards Presentation at HOF Weekend

Hall of Fame Veterans