- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Commissioner Landis’ letter sparked a historic response from FDR

#Shortstops: Commissioner Landis’ letter sparked a historic response from FDR

Curators are a curious lot. Asking questions is in their nature. Such was the case when Hall of Fame Curator of History and Research, John Odell, had the chance to work with the famous Green Light Letter.

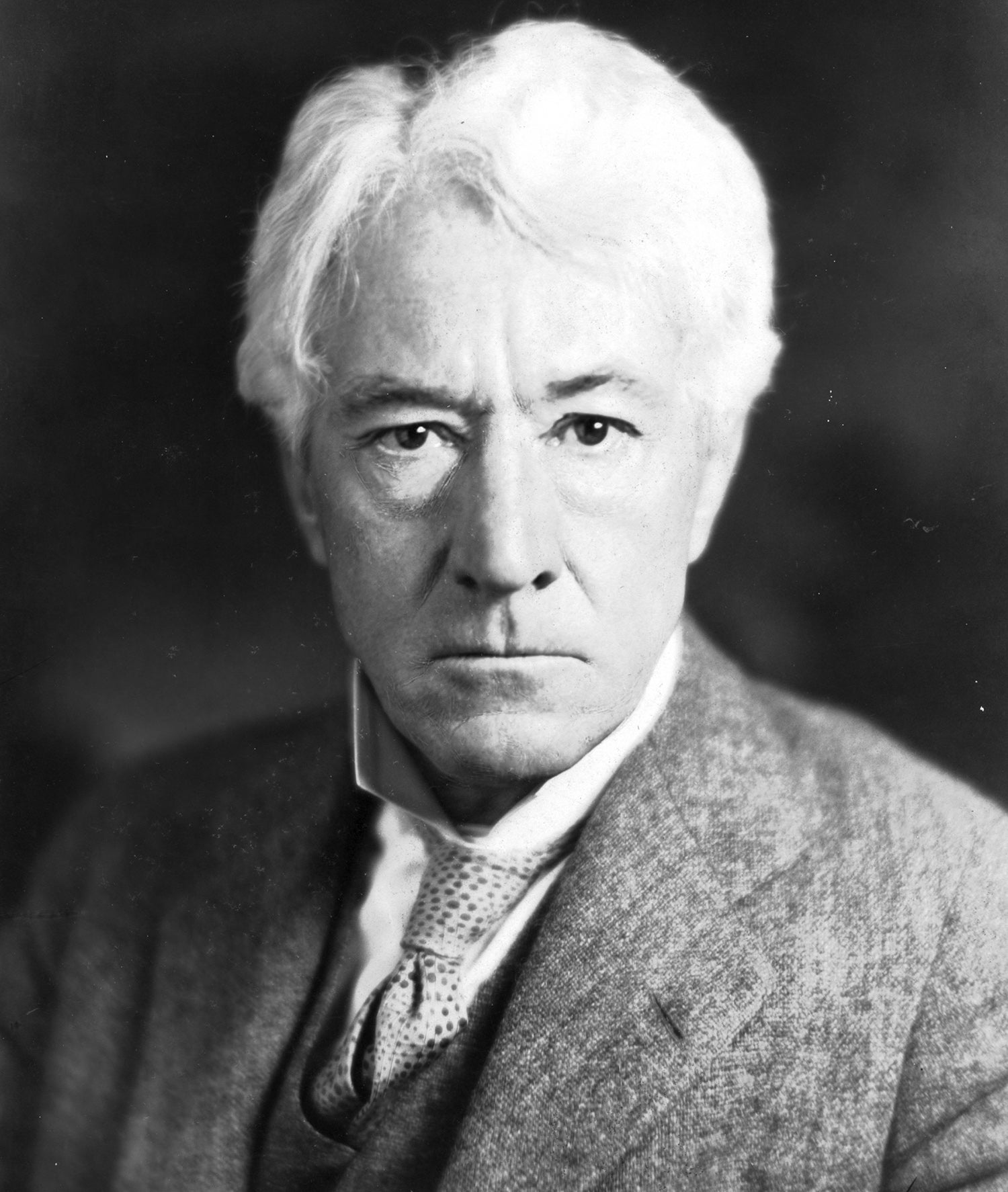

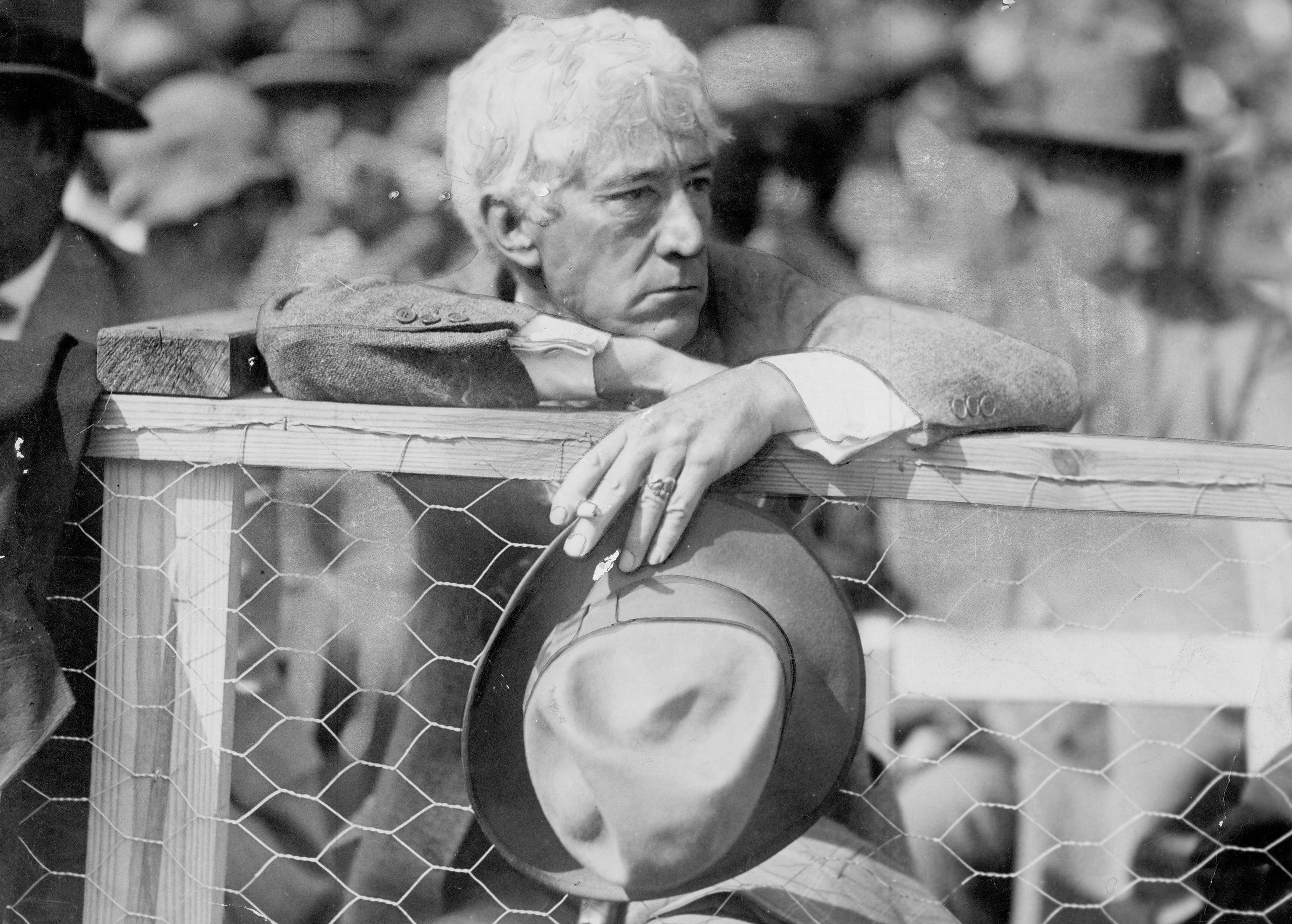

This is the document, sent by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Commissioner of Baseball Kenesaw Landis in the dark days following the attack on Pearl Harbor, which provided baseball with FDR’s personal support to continue as the nation entered World War II.

Odell had previously worked as Collections Manager at the United States Senate and was very familiar with the machinations of government paperwork. As he read the letter it occurred to him that Roosevelt was not sending an unsolicited document, but he was responding to an inquiry. If this was the Green Light Letter, was there a letter of inquiry from Landis, and if so, where was it?

Fortunately, under the direction of the National Records and Archives Administration (NARA), the United States has an active program in place to preserve the documents of the executive branch. Roosevelt’s archive is housed at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, N.Y. Having discerned the likelihood of a letter from Landis to Roosevelt, Odell contacted the archivists overseeing this collection. They quickly confirmed that such a letter existed and were pleased to provide copies for review. Americans are fortunate to have a dedicated staff of archivists and librarians working across the nation to ensure that our documented heritage is saved for future generations to study and enjoy.

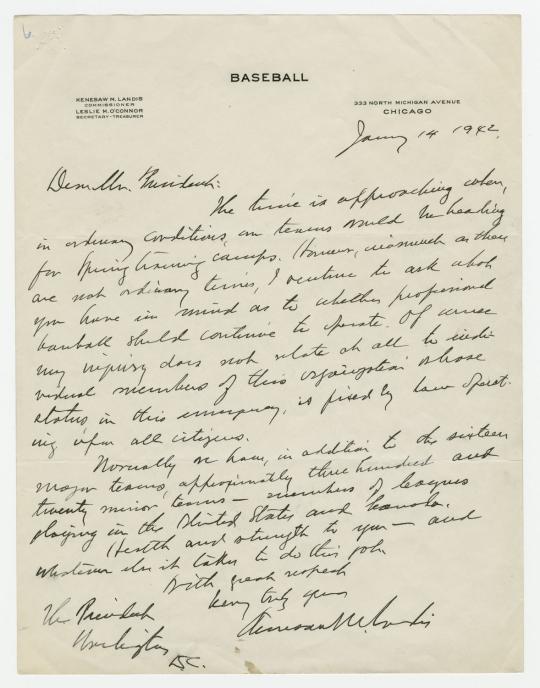

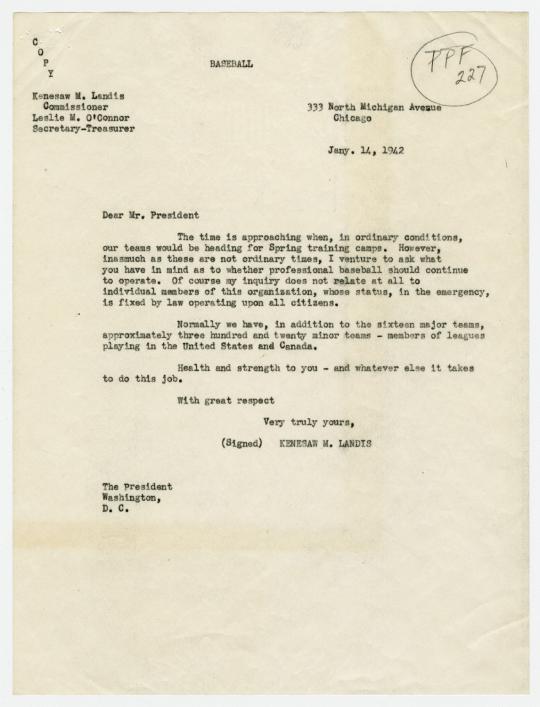

Odell designated the Landis inquiry as the “Red Light Letter,” because the crux of the communication hinged on this query, “…inasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether baseball should continue to operate.”

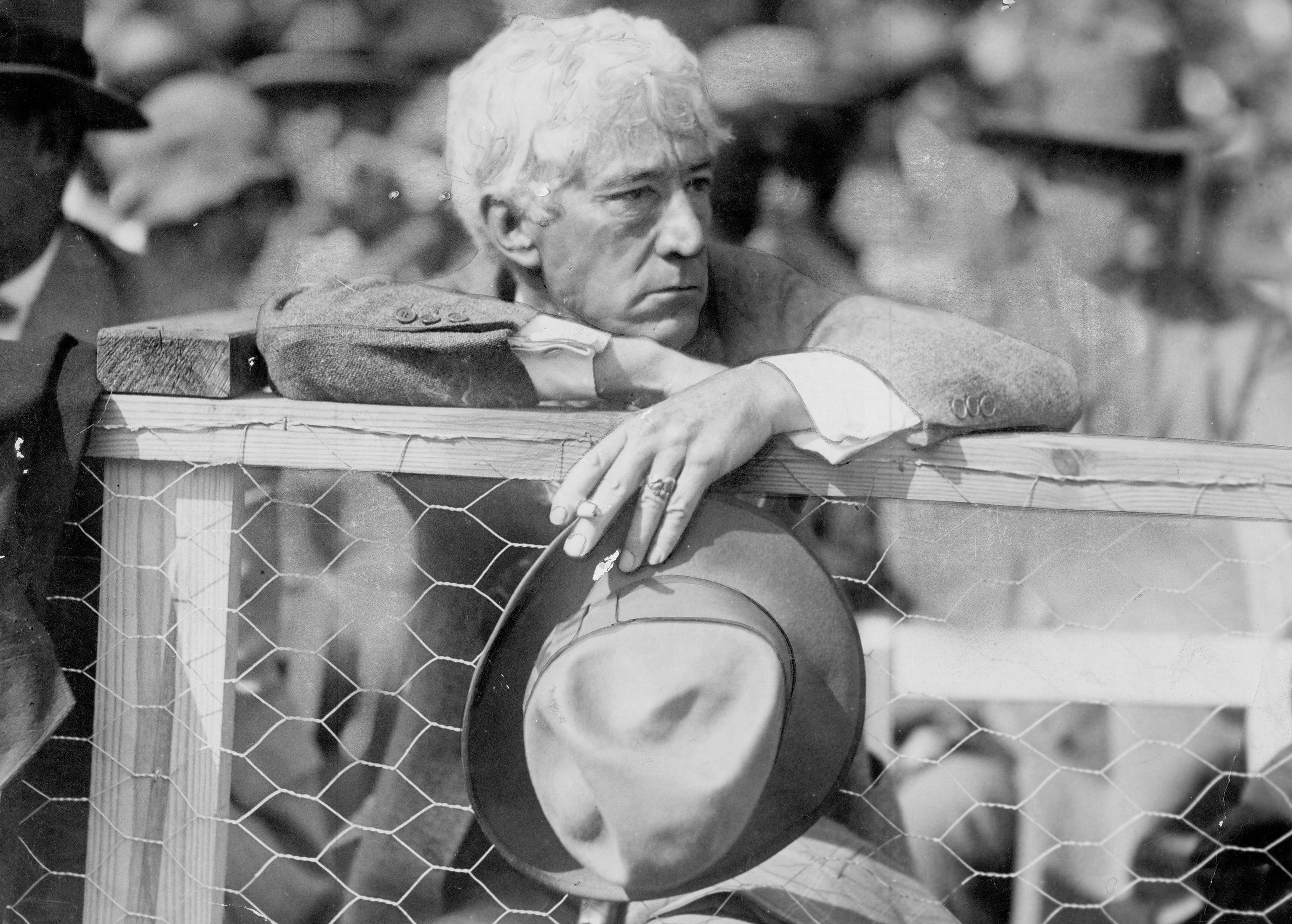

The letter was dated Jan. 14, 1942, just five weeks after Pearl Harbor. Landis acknowledges that many of the young men playing will be moving into military service, saying, “Of course, my inquiry does not relate at all to the individual members of this organization, whose status, in the emergency, is fixed by law operating upon all citizens.”

This is an important sentence as it makes clear that baseball is not asking that players be exempted from service-related duties, and thus confirms the patriotic support of a nation at war. The Commissioner is simply asking if the game should continue with whatever resources they can muster. Many ball players, including future Hall of Famers Bob Feller and Hank Greenberg had already set aside their baseball careers to enter military service, and more would soon follow. By 1945, over 500 major leaguers, 4,000 minor league players, and 230 Negro leagues players would serve their nation, in all theaters of the war.

According to Odell, there were two things which surprised him in this exchange. First, as Landis operated with a very small support staff, his original letter to the President was handwritten, not typed. Not known for his penmanship, the letter was transcribed by the White House staff on a typewriter before being placed on FDR’s desk. This would allow Roosevelt to quickly read the letter and not get bogged down by Landis’ scribble.

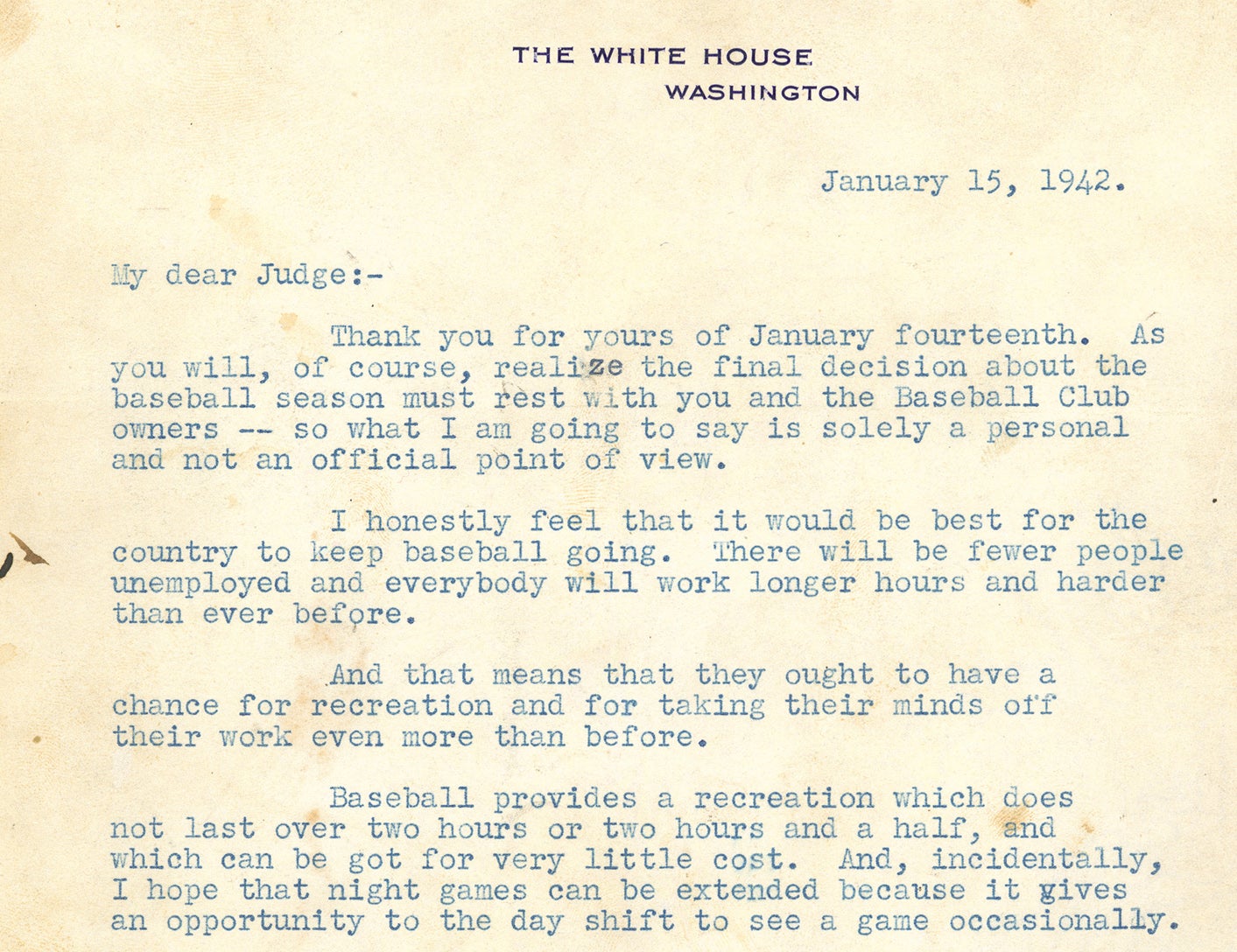

The second surprise is the speed with which the exchange occurred. Landis’ letter is dated Jan. 14 and Roosevelt’s response is dated Jan. 15. With the President trying to lead an unprepared nation into a global conflict, his hours were precious, yet he found time to respond immediately. Odell even refers to the “wonderful prose” that FDR used in his letter. It is not just a quick reply, but a thoughtfully composed letter which encourages Landis to continue with the next baseball season.

Said Roosevelt, “I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before.” The President also agrees that many players will be lost to military service, saying, “As to the players themselves, I know you agree with me that individual players who are of active military or naval age should go, without question, into the services.”

FDR then concludes the letter stating, “Here is another way of looking at it – if 300 teams use 5,000 or 6,000 players, these players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20,000,000 of their fellow citizens – and that in my judgment is thoroughly worthwhile.”

The length of the response and its thoughtful language clearly show that Roosevelt considered baseball to have an important place in our culture, something worthy of his valuable time. Even during a major crisis, using a diminished resource base, baseball should continue for all to enjoy. Despite all the time and energy needed to lead a nation preparing for a global conflict, he felt it necessary to prepare letter which spelled out why baseball would be important to the citizens of a nation at war.

Thus, with the help from the FDR Library, Odell was able to pull all the pieces of the story together, giving us a chance to share it with everyone.

“One of the neat little pleasures we have at the Baseball Hall of Fame,” Odell said, “is to have access to the resources to close the loops of history.”

Jim Gates is the Librarian Emeritus at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

Team Tours of Japan bridged cultural gap following World War II

Commissioner Landis frees 74 Cardinals farmhands

#GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

Team Tours of Japan bridged cultural gap following World War II