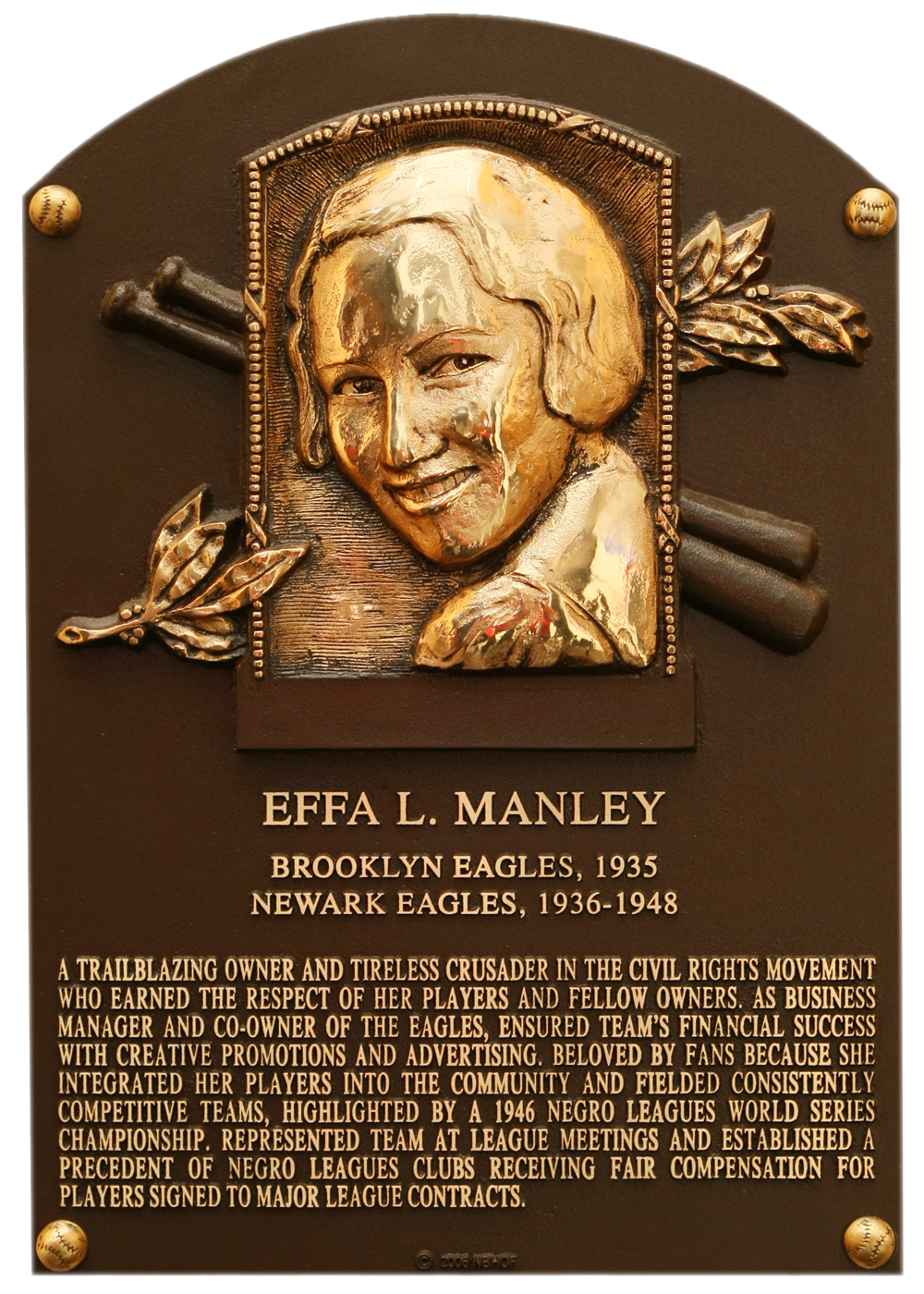

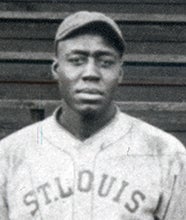

As a businesswoman in a primarily man’s world, Effa Manley wanted to be a winner. Though the only woman among an industry of male owners, Manley got her wish in 1946, when the Newark Eagles, owned by her and her husband Abe, won the Negro League World Series, defeating the Kansas City Monarchs.

Her career is a testament to her commitment to baseball and civil rights – and to her vision and dedication to creating respect for Negro Leagues baseball.

Born on March 27, 1897, Manley grew up in Philadelphia, but her commitment to the game and civil rights began when she moved to New York following high school. Often found at Yankee Stadium watching Babe Ruth, Manley dedicated her time to local social organizations and causes. For example, in 1935 she walked the picket line in a successful campaign to get local businesses to hire African-American employees, a “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign.

While attending one of the World Series games in 1932, Manley met her future husband, Abe. Nearly 15 years her senior, Abe had already established his reputation in the local community as a baseball man. Together they forged a partnership that resulted in the rapid rise to fame of the Newark Eagles, a team they owned from 1935 (moved from Brooklyn to Newark in 1936) until she sold the club to a group of investors in 1948.

Her position as co-owner of the Eagles included handling contracts and travel schedules for the Eagles, and she quickly gained recognition across the league for her ability to promote the team. Fellow owner Cumberland Posey remarked that the league could learn something from Manley’s keen sense of promotion. Manley also displayed personal care for the team’s players on and off the field, assisting them with jobs, serving as godparents to some and purchasing a $15,000 bus for the team’s travel – always working to get players the best available accommodations on the road.

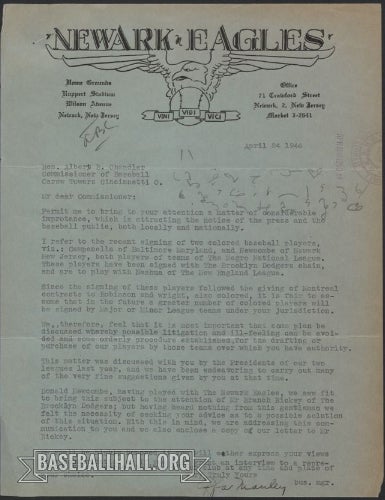

Perhaps Manley’s greatest contribution as an owner would come in her final years with the Eagles. Following Branch Rickey’s signing of Jackie Robinson from the Negro Leagues to play Major League Baseball, Manley fought for compensation for team owners and recognition of the Negro Leagues contracts. A few months following Robinson’s entry into the major leagues in 1947, Manley and the Negro Leagues received compensation for Larry Doby, the first African American to play in the American League, thereby establishing a precedent for player compensation. The move showed the legitimacy of the Negro Leagues, giving the teams a measure of respectability never before seen from the majors.

Throughout her ownership, Manley pushed the envelope to develop a better league, emerging as a leading voice among Negro Leagues owners.

“Mrs. Manley knows a few things about baseball and most of the men club owners could take a few tips from her. She is a good business woman,” wrote Chicago Defender reporter Fay Young in December 1943.

Manley also used her position with the club to promote a variety of causes and benefits. The team invited soldiers during World War II to Eagles games for free. The club hosted benefits for causes such as the Harlem Fight for Freedom Committee and the Newark Community Hospital. One of the benefit games featured a “Stop Lynching” theme, with ticket takers collecting donations and wearing sashes to promote the cause.

The Eagles boasted a number of excellent players during Manley’s tenure as owner, and their success culminated with the 1946 Negro League World Series triumph. The great Eagles rosters included future Hall of Famers Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Biz Mackey, Mule Suttles and Willie Wells.

Off the field, Manley was a well-known civil rights advocate, frequently leveraging the Eagles’ influence to promote charitable causes, equality boycotts, anti-lynching activism, and social services for Black servicemen during World War II.

Manley’s personal connection with race was complicated. Her light-skinned (and possibly mixed-race) mother was married to a Black man, but Manley’s biological father was white. Regardless of her racial background, Manley claimed the Black community as her own and always embraced it.

Following her ownership tenure, Manley co-authored a book on black baseball with Leon Hardwick, and she donated her scrapbook chronicling her time as owner to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. She also wrote letters lobbying for Negro Leaguers to be admitted into Cooperstown.

Manley passed away on April 16, 1981. She became the first woman elected to the Hall of Fame in 2006.