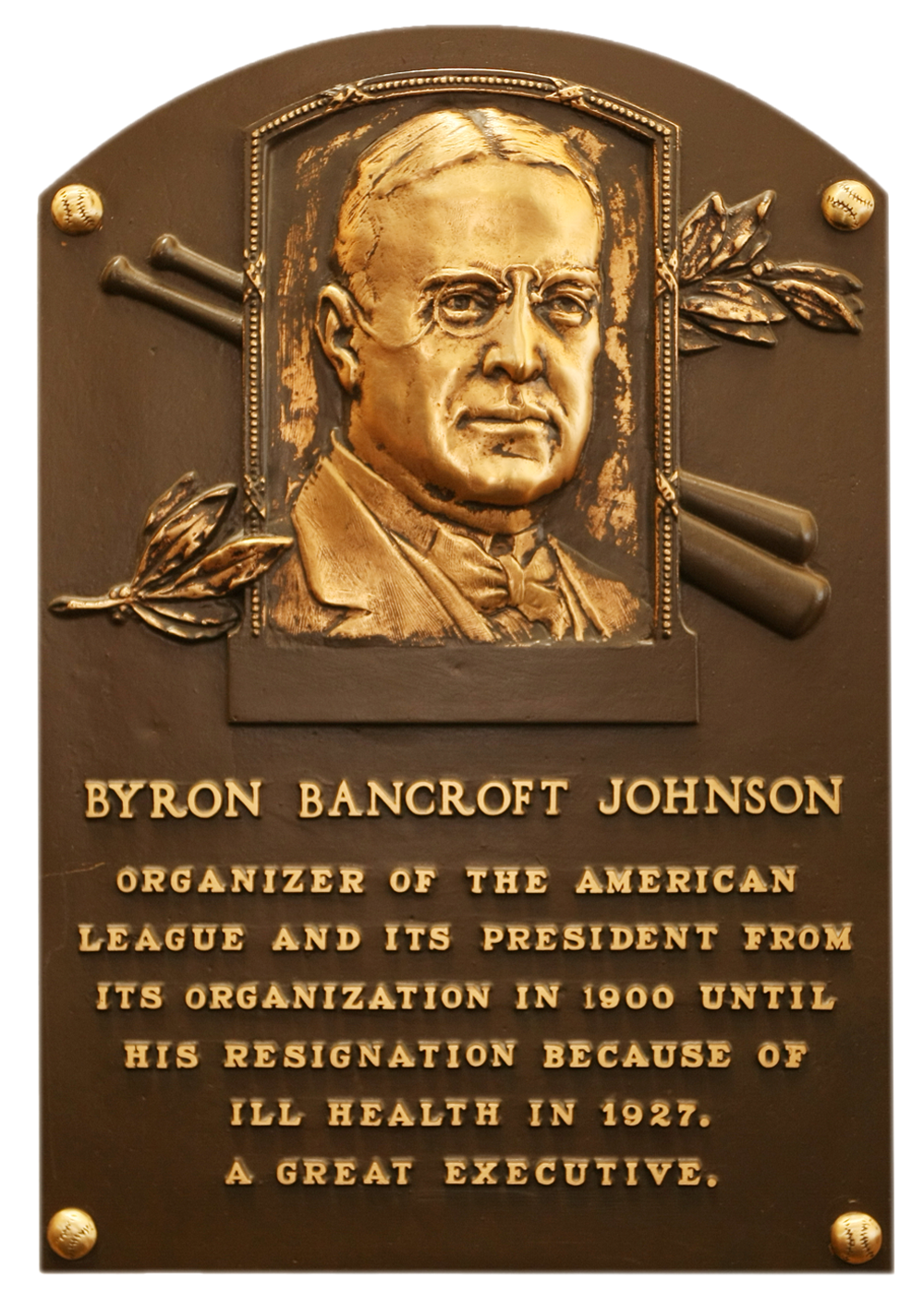

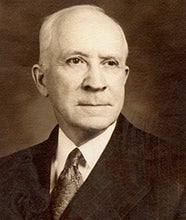

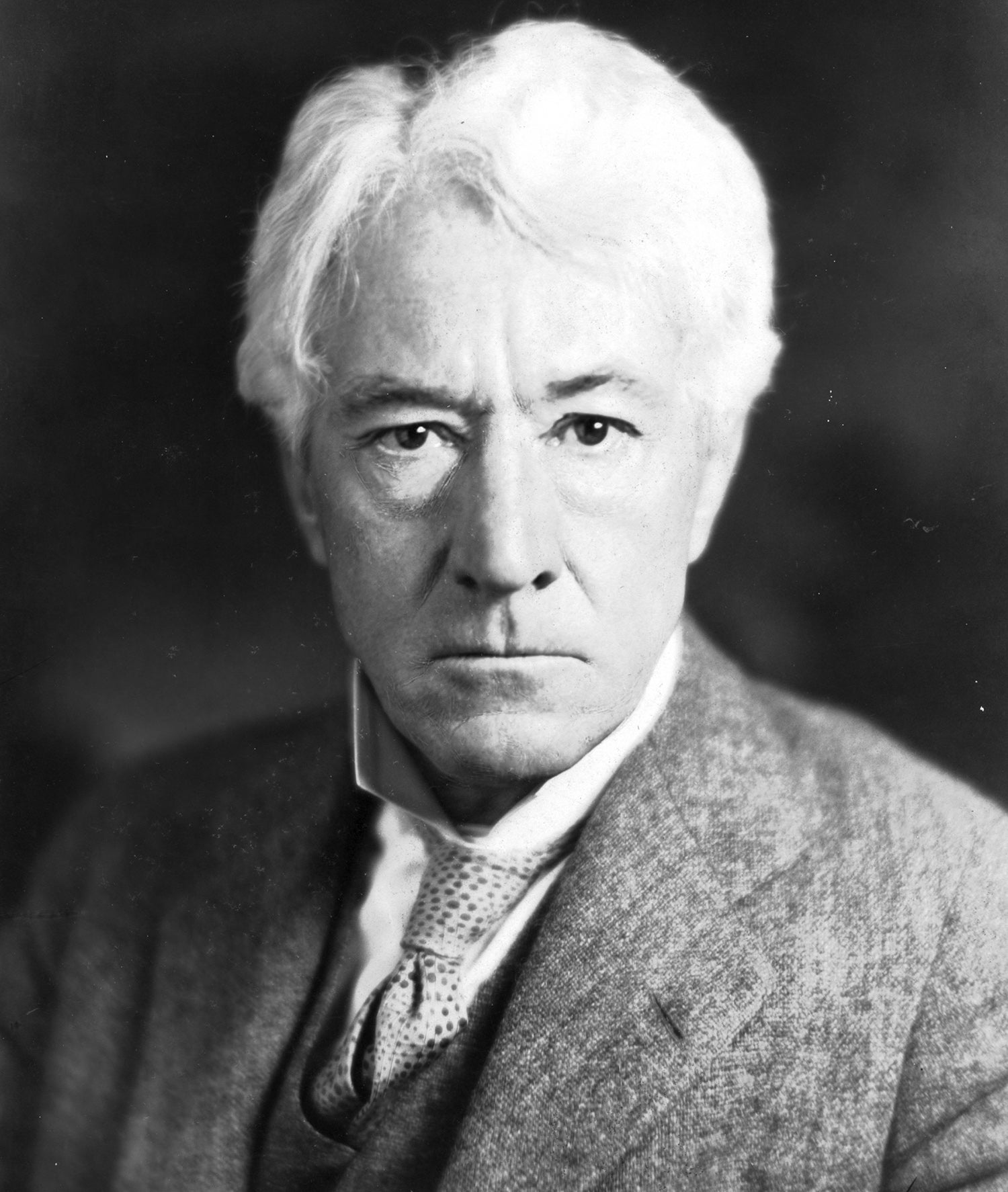

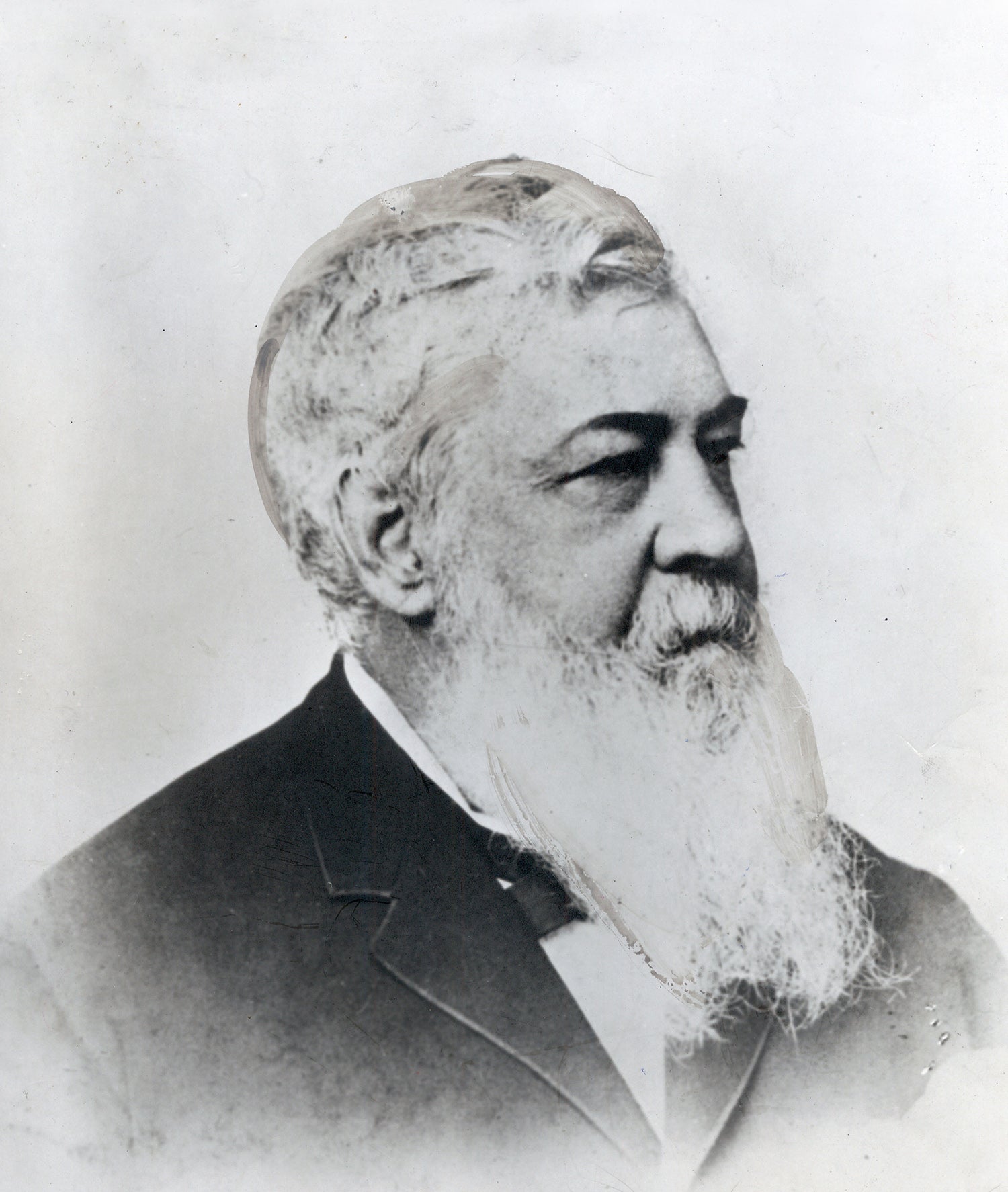

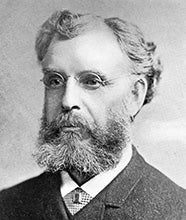

An ambitious, driven leader, American League founder Ban Johnson was baseball’s most influential executive for more than a quarter of a century.

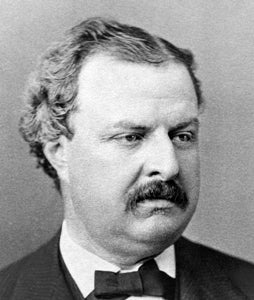

Johnson was a sportswriter for the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette in the early 1890s who became an outspoken critic of the rowdy atmosphere in the National League. He also decried Cincinnati Red Stockings owner John T. Brush for being too interested in turning profits and acting as a “representative of interests best divorced from baseball.”

In 1894, Red Stockings manager and future Hall of Famer Charles Comiskey urged Johnson to take over as president of the faltering Western League. Johnson obliged and set to work in transforming the minor league into a moral example for baseball.

The new president staunchly supported his umpires and encouraged them to eliminate rough-and-tumble play from the field. He also fined and suspended players who used foul language. Soon, the Western League was seen as both a family-friendly league and the best-run circuit in the game.

“No odds were too great for Ban Johnson to face,” said pitcher Ed Brandt. “The bigger they were, the better he liked them.”

In 1900, Johnson renamed the loop the “American League” and placed franchises in Cleveland and Chicago. The following year, Johnson’s AL claimed major league status, setting itself up for a direct confrontation with the firmly established National League.

The turn of the 20th century saw a fierce competition ensue between the National League and the new “Junior Circuit,” and Johnson’s league found nearly instantaneous success as the counterpart to the NL. American League teams were able to raid National League rosters with offers of better pay, recruiting nearly 100 players. Furthermore, the combination of star players and clean play helped the AL trounce the NL in attendance during its first two seasons. In 1903, the AL’s Boston Americans defeated the NL’s Pittsburgh Pirates in the first modern-day World Series.

Desperate to establish peace, the NL formed a “National Agreement” with Johnson that officially recognized the AL as a second major league. The agreement also set up a three-man National Commission to run Major League Baseball, and Johnson was soon acknowledged as its undisputed leader.

“Ban Johnson succeeded in establishing his American League as an equal rival of the National,” said baseball historian Lee Allen. “That crowning success elevated baseball to a high level of public acceptance and forced the birth of the modern game. For a half century, there would not be a single change of franchises. Baseball would grow up.”

Under Johnson’s leadership, baseball’s attendance numbers soared and the game rose to prominence as America’s National Pastime. Johnson banned liquor from all major league parks, cracked down on violent players and continued to upgrade the umpiring staff.

"A good umpire is the umpire you don't even notice,” Johnson said. “He's there all afternoon but when the game is over, you don't even remember his name.”

After the Black Sox scandal broke in 1920, team owners appointed Kennesaw Mountain Landis to have lone authority as baseball’s first commissioner. Though the iron-willed Johnson continually clashed with the equally headstrong Landis, he continued to serve on baseball’s National Commission until his resignation in 1927.

"They say the lion was getting old, that his roar had become a mumble; it may be so,” wrote the Sporting News. “But never, maybe, will be heard again such a voice. The roar that struck terror to evil doers, in high estate or low, and thrilled to new encouragement those who had ideals and the vision Ban Johnson had."

Hall of Fame executive Branch Rickey would go on to say that Johnson’s “contribution to the game is not closely equaled by any other single person or group of persons.”

Johnson passed away on March 28, 1931. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1937.