Foster’s strategy defined Negro Leagues

So have you heard the one about the team that laid down 11 consecutive bunts in a game? That sounds like something out of the playbook of an old school manager like Gene Mauch or Billy Martin. Mauch, in particular, loved to call for the sacrifice bunt, even early in games. Doing so 11 times in a row might have given him an unusual degree of satisfaction bordering on delight.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

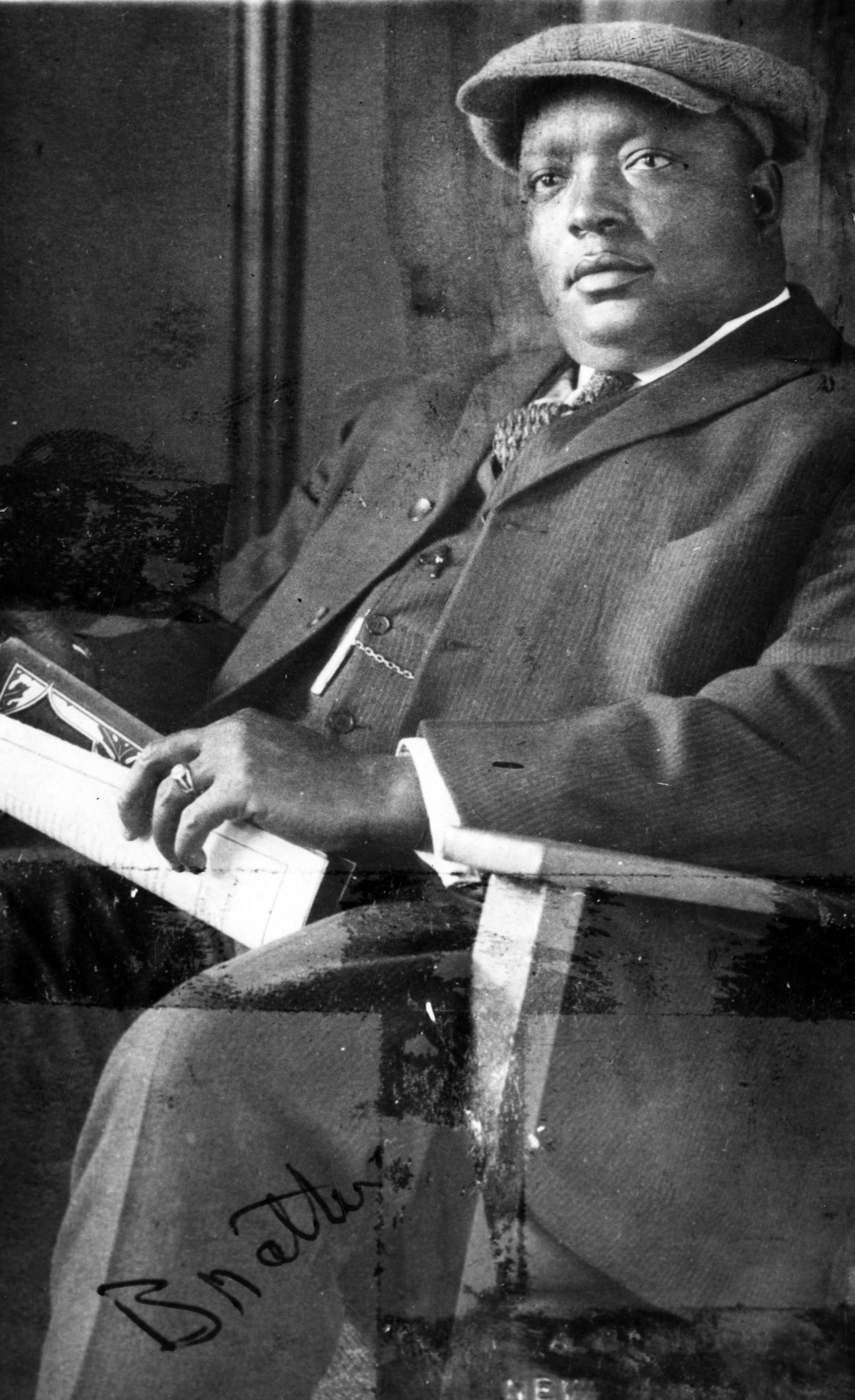

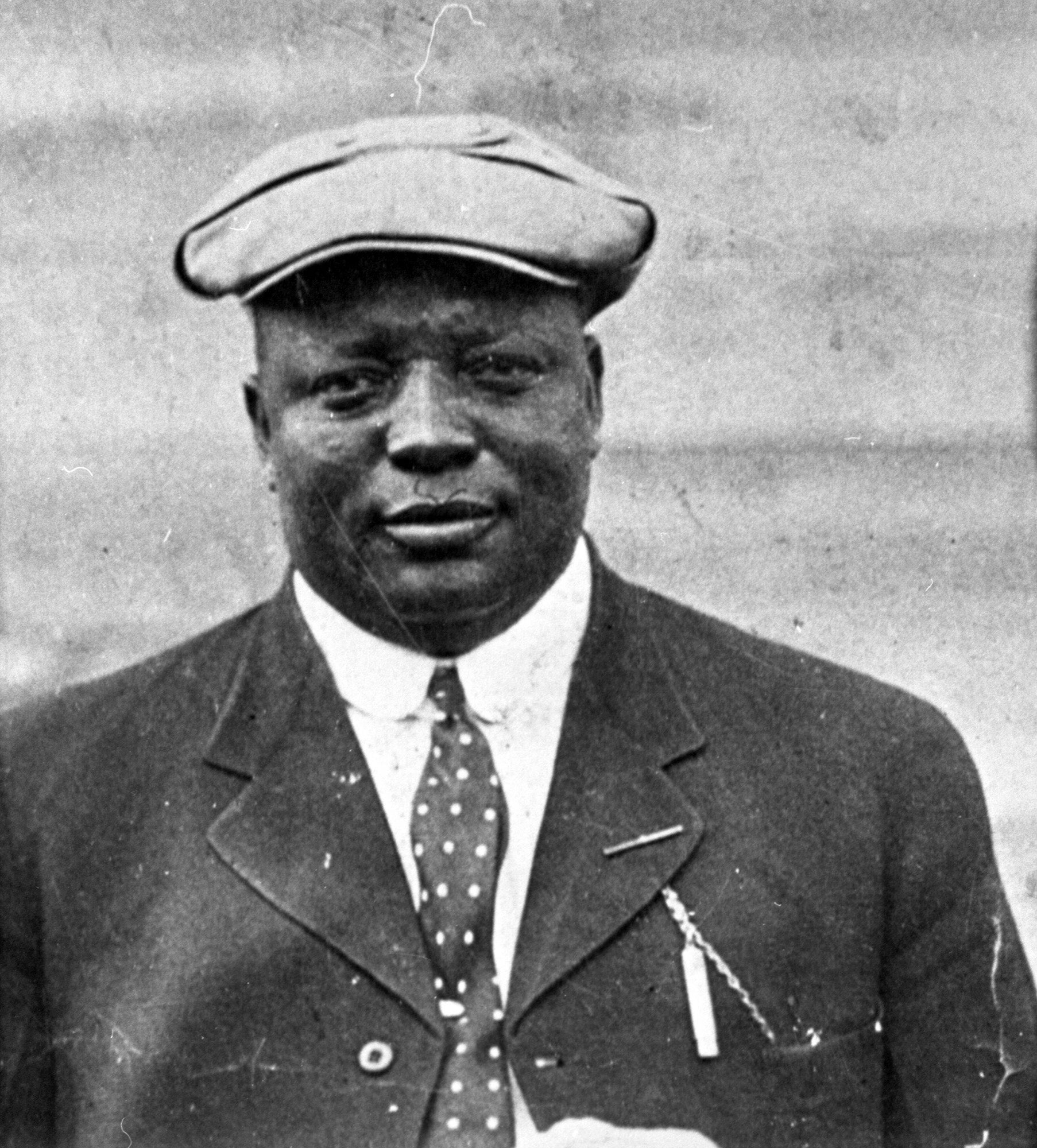

Well, Mauch never did orchestrate such a bunting marathon. Nor did Martin. As a matter of fact, it’s not exactly certain that the cascade of 11 straight bunts ever did occur, but it does appear that something close to it took place in a Negro Leagues game more than a century ago. And it was all done under the direction of Hall of Famer Rube Foster, the founder of the Negro Leagues who was managing the Chicago American Giants at the time.

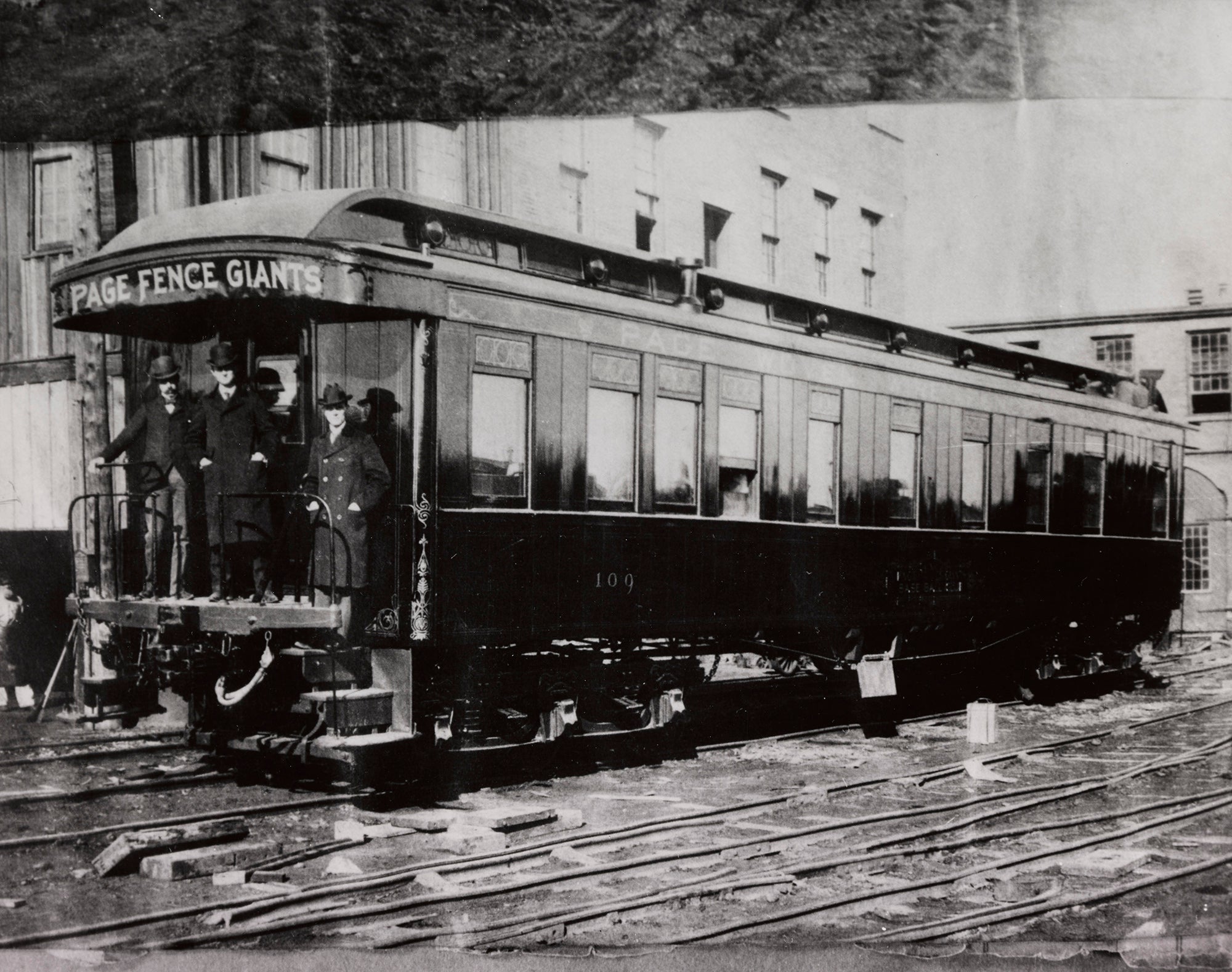

In the meantime, darkness was descending on Washington Park. Like all of the Negro Leagues ballparks at the time, the stadium had no lights at all. (Night baseball would not come to the Negro Leagues until the 1930s, when the Kansas City Monarchs spearheaded the innovation.) With the score still tied at the end of regulation, the umpires ruled that it was too dark to continue play. The arbiters called the game, declaring it a tie at 18-18, thus infuriating the fans at Washington Park.

Foster would not accept the excuse that great hitters did not need to learn how to bunt; it was a skill that was regarded as mandatory, without exception. In order to ensure that his hitters mastered the art of bunting, Foster used a special bunting drill, in which each player had to place a bunt into Foster’s hat, regardless of where it was placed on the field.

Simply put, Foster believed that bunting led to winning games. That’s exactly what happened in that 1921 game against Indianapolis. Regardless of the exact number of bunts the American Giants executed that day, it’s safe to say that nothing like this will happen in today’s game – or in the foreseeable future. In an age when statistical analysis tends to frown upon the benefits of the sacrifice bunt, the idea of a bunting extravaganza would seem far-fetched. The closest occurrence to it can be found in a game in 2015, when the Arizona Diamondbacks went a little bunt-happy and laid down three consecutive bunts. But that’s still well short of what Rube Foster and his Chicago American Giants did over 100 years ago.

To the chagrin of some, the almighty bunt will likely never be so exalted again.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum