Page Fence Giants succeeded on and off the field

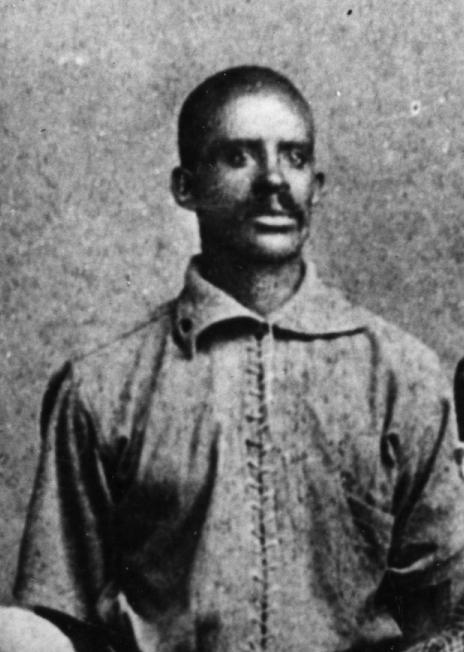

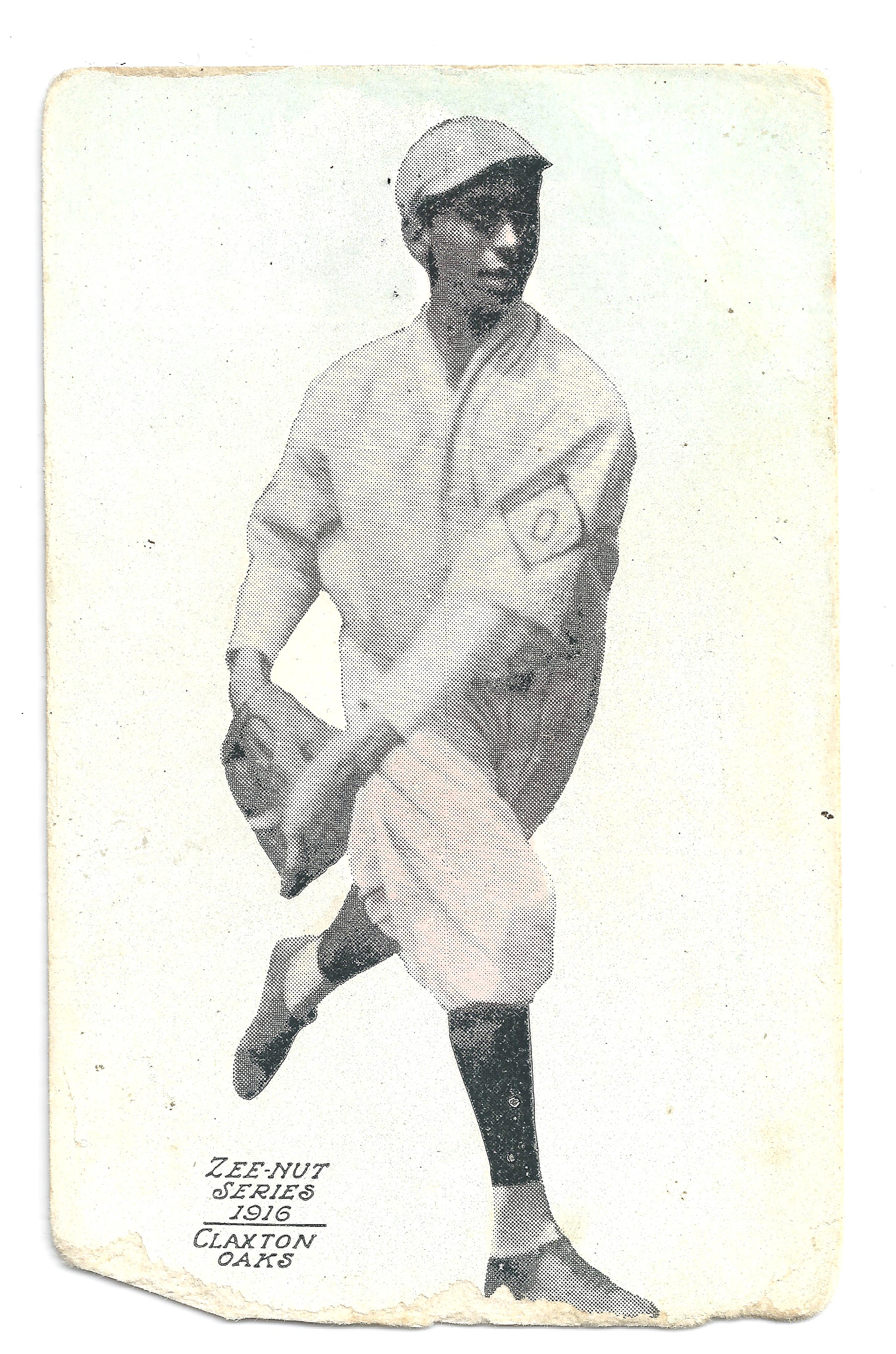

In 2022, Bud Fowler earned election and induction to the Hall of Fame. Though he never appeared in what would officially be regarded as a major league game, his long career as a dominant player stands high among his accomplishments.

Another aspect of his career also merits praise: his leadership and vision in forming a team with the unusual name of the Page Fence Giants.

In 1894, Fowler was playing for an integrated and unaffiliated minor league team in Findlay, Ohio. An intelligent, well-organized and driven man, Fowler wanted to create something more notable and impactful in Findlay: a team consisting of Black stars that he planned to call the Findlay Colored Western Giants.

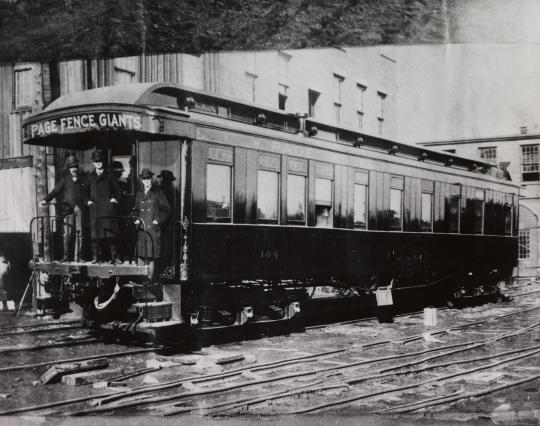

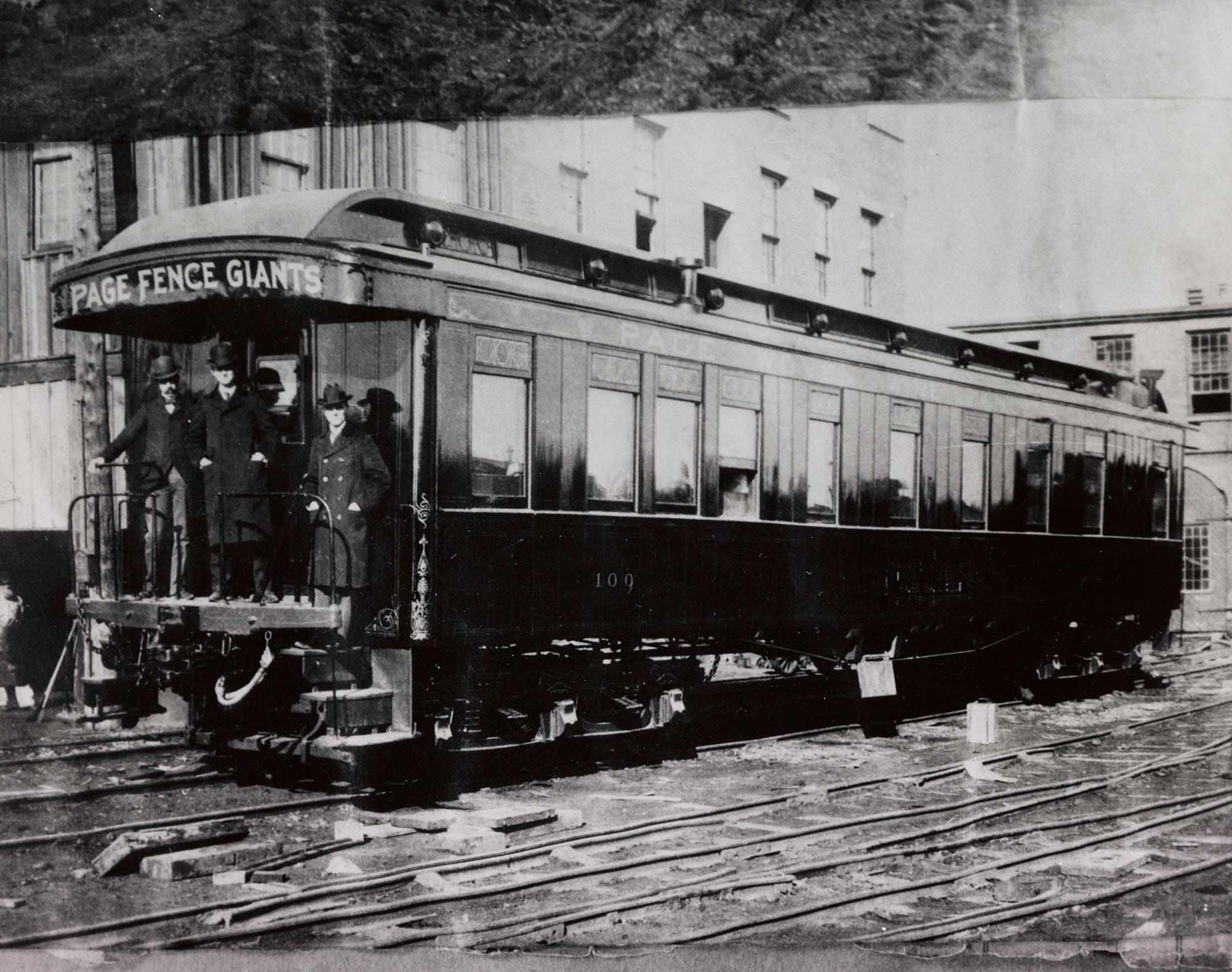

Fowler sought some help from his lone Black teammate in Findlay, shortstop Grant “Home Run” Johnson. Fowler wanted Johnson, a native of Findlay and a college-educated player, to join him on the new team. Their vision was to create an all-Black team that would travel the country in a luxurious private railcar while taking part in street parades prior to each of their games.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Giants generated enough interest to draw an average crowd of 1,500 fans per game that season. While that might not sound like a large turnout, it’s worth noting that the Giants often played in smaller towns with modest populations, as opposed to large-city venues. With decent crowd support, the team was able to turn a profit, though Page reportedly did not pocket the money. Satisfied with the Giants as a promotional vehicle for his fence company, Page instead put the money back into the team. He paid the players at a rate similar to other Black barnstorming teams. According to Black baseball historian Larry Hogan in his book, Shades of Glory, the Giants players were paid anywhere from $75 to $100 per month, commensurate with what other top Black players of the era were receiving.

Sadly, the Giants also faced difficult moments during their first season. Giants management disputed the outcomes of some of their losses, claiming that unfair calls by biased umpires had directly affected the course of the game. And then there was the horrific tragedy that involved one of the Giants’ players. During a June game in Hastings, Mich., center fielder Gus Brooks collapsed on the field. He was then taken to a hotel, where he died a few hours later. Brooks, a standout defensive center fielder, was only 23 years old.

Brooks’ death marred a tumultuous season for the Giants. The midseason departure of Fowler also created difficulty for a team that had come to rely not only on his playing skills, but also his ability to organize, lead, and promote the team.

Even with Fowler’s early withdrawal, the Giants remained a viable franchise for a period of four seasons. They also remained a dominant team, winning a remarkable 143 games in 1896, and then following up with 129 and 107-win seasons. The 1897 season included a mind-numbing 82-game winning streak.

As with many Black ballclubs, the Giants’ run came to an end because of financial difficulties, and not because of any lack of playing ability. Forced to dissolve in 1898, the franchise was then moved to Chicago in 1899, when the team became known as the Chicago Columbia Giants.

Ultimately, the Page Fence Giants lasted for only the four seasons. Yet, their impact as a dominant black franchise in the era before the formation of the Negro Leagues, coupled with their ability to entertain fans with parades, on-field stunts, and quirky gimmicks, made them a national sensation— – and a vital and fascinating part of Black baseball history.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum