- Home

- Our Stories

- Card Corner: 1979 Topps Don Stanhouse

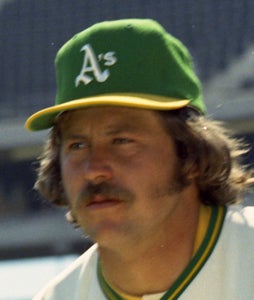

Card Corner: 1979 Topps Don Stanhouse

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As George Costanza once said to Elaine on an episode of Seinfeld, “Let me tell you something, no one walks into a beauty parlor and says, ‘Give me the Larry Fine!’ ”

For those who don’t remember, Larry Fine was one of the members of the “Three Stooges” comedy troupe. He had an unusual hair style to say the least, with bushy, curly hair on the sides, and a smaller coiffeur of hair on top of his head. He often looked like he hadn’t run his hair through a comb in days. It was not attractive - some would call it unsightly - but it did lend itself well to the zany comedic exploits of the Stooges.

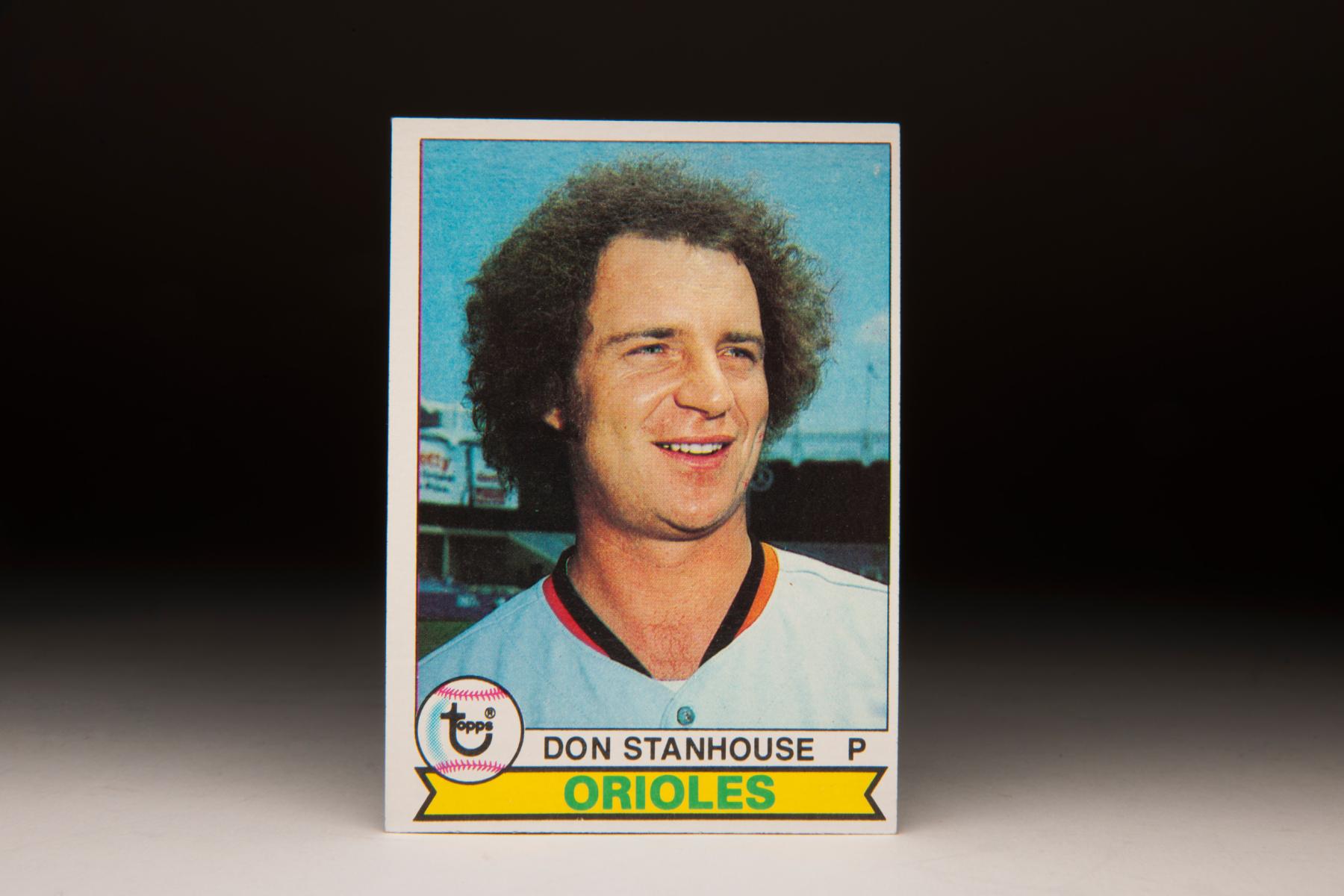

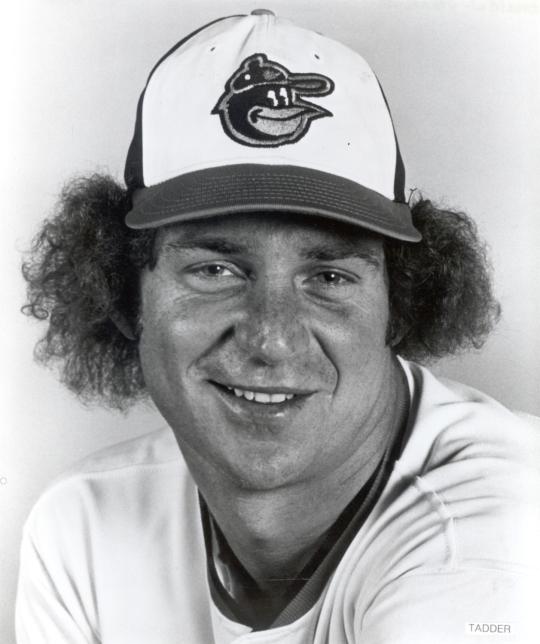

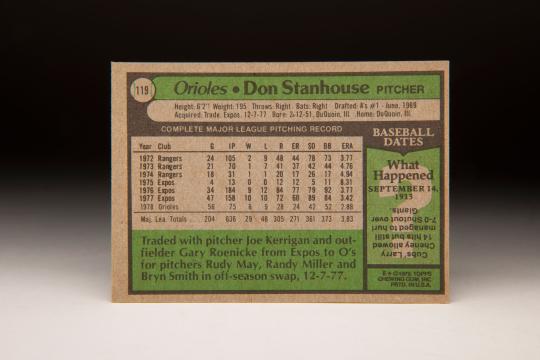

Larry Fine’s memorable hair came to mind the other day when I looked at Don Stanhouse’s 1979 Topps card. I had seen this card dozens of times before, but never made the connection to Fine until now. Don Stanhouse, with that fully permed hair blown out on either side of his head, looks a little bit like the famed comedian who helped make the Three Stooges Hollywood legends.

Perms and Afros were common among ballplayers in the late 1970s. Just ask Jose Cardenal, Oscar Gamble, Ross Grimsley or Bake McBride. Yet most of those hairstyles lacked the goofiness of the Stanhouse hair. Their Topps cards usually covered up their hair - or at least part of it - with a cap or a helmet. But that is not the case with the Stanhouse card. Whether intentionally or not, Topps photographed Stanhouse without a cap, so that we could appreciate his hairdo in all of its glory. That hairdo looked ready made for a 1970s appearance on Saturday Night Live or Second City TV. And it’s appropriate that Stanhouse would wear a hairstyle reminiscent of the Three Stooges, given his own wild tendencies, colorful sayings, and generally offbeat sense of humor.

“I’m not the prettiest guy in the world,” Stanhouse told the Associated Press in 1979. “But I’m not Igor either. I’m pretty on the inside. When they took X-Rays of my head, they found flowers.”

Such quotations provide insight into the wacky world of Don Stanhouse. His professional career began a bit more sanely (and with straighter hair) in 1969, when the Oakland A’s drafted him as a third baseman. During his first minor league season, the A’s approached Stanhouse about switching positions and becoming a pitcher. He was at hesitant at first, but his minor league manager, Hall of Famer Billy Herman, explained that he could make the major leagues much faster as a pitcher than as a position player. Once Stanhouse heard that line of reasoning, he agreed to the switch.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Sure enough, Stanhouse seemed primed and ready to make the Oakland roster by the spring of 1972, only three years after being drafted. The A’s already had a veteran quartet of starters in Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, Ken Holtzman and Blue Moon Odom, but they needed a fifth starter. When Blue decided to hold out during the spring, the A’s suddenly had a need for two starters. Stanhouse believed he would be one of the two.

It didn’t happen. Late in Spring Training, A’s owner Charlie Finley, a man who loved to add brand-name players to his roster, arranged to make a trade with the Texas Rangers. The deal brought onetime 31-game winner Denny McLain to Oakland, at the cost of two young pitchers in the organization, right-hander Jim Panther and Stanhouse himself. Just like that, Stanhouse was gone, never to wear the green and gold of the A’s in an actual major league game.

The Rangers needed pitching more than the A’s, so Texas included Stanhouse on its Opening Day roster. The 1972 season opened late because of the player strike, delaying Stanhouse’s major league debut until April 19. Stanhouse pitched well that day, striking out nine Chicago White Sox while allowing only one run in six and two/thirds innings. Powered by a live fastball, he earned his first big league victory.

Remarkably, Stanhouse would win only one more game that season. He pitched respectably, to the tune of a 3.78 ERA, but the Rangers played poorly behind him. In fact, the Rangers played poorly behind most of their pitchers. As a team, Texas won only 54 games. So Stanhouse’s record of 2-9 was more than understandable.

In 1973, Stanhouse started the season poorly, losing five decisions and watching his ERA rise above 4.00. Rangers manager Whitey Herzog demoted Stanhouse to the bullpen, but he continued to struggle. With a tendency to walk more batters than he struck out, he was an especially bad fit for late-inning relief.

While with the Rangers, Stanhouse began to foster his reputation for mischief and offbeat behavior. Herzog once criticized Stanhouse for spending too much time on the mound staring at women in the stands rather than concentrating on the hitter in the batter’s box. After recording his first major league save, Stanhouse boarded the team flight, which the Rangers shared with other travelers. Stanhouse began to stalk the aisles, signing napkins and stuffing them into the shirts of some of the other passengers, who had no idea who he was or why he was signing autographs.

Later in 1973, the Rangers demoted Stanhouse to Triple-A Spokane. During one of Spokane’s flights, Stanhouse and one of his minor league teammates were forced to leave the plane during a stopover. Stanhouse had done nothing wrong, but had merely defended his teammate, who had exchanged words with a stewardess. Not fully understanding what had happened, the Rangers became upset with Stanhouse and refused to bring him up in September when the rosters expanded.

Despite a growing anti-establishment reputation, the Rangers brought him back to Texas in 1974 and made him a full-time reliever. His control improved a bit, but his ERA and his overall performance did not. After the season, the Rangers packaged Stanhouse with infielder Pete Mackanin, and sent the pair to the Montreal Expos for veteran outfielder Willie Davis.

To his surprise, Stanhouse did not make Montreal’s Opening Day roster in 1975. Instead he started the season at Triple-A. The Expos brought him up in midseason, but he pitched so poorly that it was evident something was wrong. Determining that Stanhouse was hurt, the Expos placed him on the disabled list, ending his season after only four big league appearances.

Returning to health in 1976, Stanhouse fought his way into the Expos’ starting rotation. Despite walking more batters than he struck out, he pitched creditably for the Expos and won nine games, an impressive total for a last-place team. The following season, he started the season in the rotation, only to have new manager Dick Williams move him into a relief role in midsummer. Stanhouse wasn’t thrilled by the decision, but he blossomed in the bullpen. Pitching 31 games in relief, Stanhouse spun an ERA of 1.52 and saved 10 games. He appeared to be the Expos’ closer for the foreseeable future.

Unfortunately, Stanhouse’s off-the-field antics did not thrill his manager. Also, he wanted more money from the Expos. When contract negotiations hit a snafu, the Expos decided to include him in a major wintertime deal with the Baltimore Orioles. The trade sent Stanhouse, right-hander Joe Kerrigan and outfielder Gary Roenicke to Baltimore for three pitchers, including veteran lefty Rudy May and prospect Bryn Smith.

The Orioles hoped the addition of Stanhouse would address their bullpen needs. Tim Stoddard and Tippy Martinez endured slow starts to the 1978 season, but Stanhouse stood out. Despite a continuing habit of walking batters, Stanhouse closed down his share of games in the ninth inning, emerging as manager Earl Weaver’s new relief ace.

While with Baltimore, Stanhouse solidified his reputation as one of the game’s free spirits. “Look at him,” Orioles catcher Rick Dempsey told the Chicago Sun-Times. “He only wears black clothes, everything in his house is black, his car is black. He’s even got a damned stuffed gorilla over his locker that’s black. (He) wants to be a mortician.” Stanhouse also had a strange habit of pretending to fall asleep on the mound, which annoyed a few hitters and umpires along the way.

It didn’t take long for one of Stanhouse’s Orioles teammates to come up with a nickname for the flaky right-hander. Left-hander Mike Flanagan began calling the reliever “Stan the Man Unusual.” The nickname stuck like glue - gorilla glue to be more appropriate.

Even on the mound, Stanhouse could be adventurous. Although he saved 24 games for the Orioles in 1978, the most saves ever recorded by a reliever under Weaver, he often walked a tightrope in the late innings. In 74 innings, he walked 52 batters. Stanhouse claimed it wasn’t a case of intentional wildness, but rather a case of not wanting to give in to the hitter. “I know I have too many walks for a relief pitcher and I know the reason I walk so many,” Stanhouse told Orioles beat writer Jim Henneman of the Baltimore Sun. “It’s because I won’t throw [over] the middle of the plate. It’s just the way I pitch.”

That way drove Weaver to distraction. Known for smoking cigarettes during games, Weaver increased his tobacco consumption whenever Stanhouse entered games. Weaver told reporters that he came up with a new nickname for Stanhouse: “Full Pack.” That’s because he sometimes smoked a full pack of cigarettes during one of Stanhouse’s walk-filled appearances.

Despite the nervousness that accompanied his relief outings, Stanhouse remained effective in the closer’s role in 1979. In fact, he made the All-Star team and helped the Orioles win the American League East title.

Stanhouse did not pitch as well in the postseason. In Game 2 of the World Series against the Pirates, he took the loss, giving up the deciding run on Manny Sanguillen’s pinch-hit single. Like the rest of the Orioles, Stanhouse came away disappointed, as Baltimore allowed a three-games-to-one lead to fritter away, resulting in a Game 7 loss to Pittsburgh.

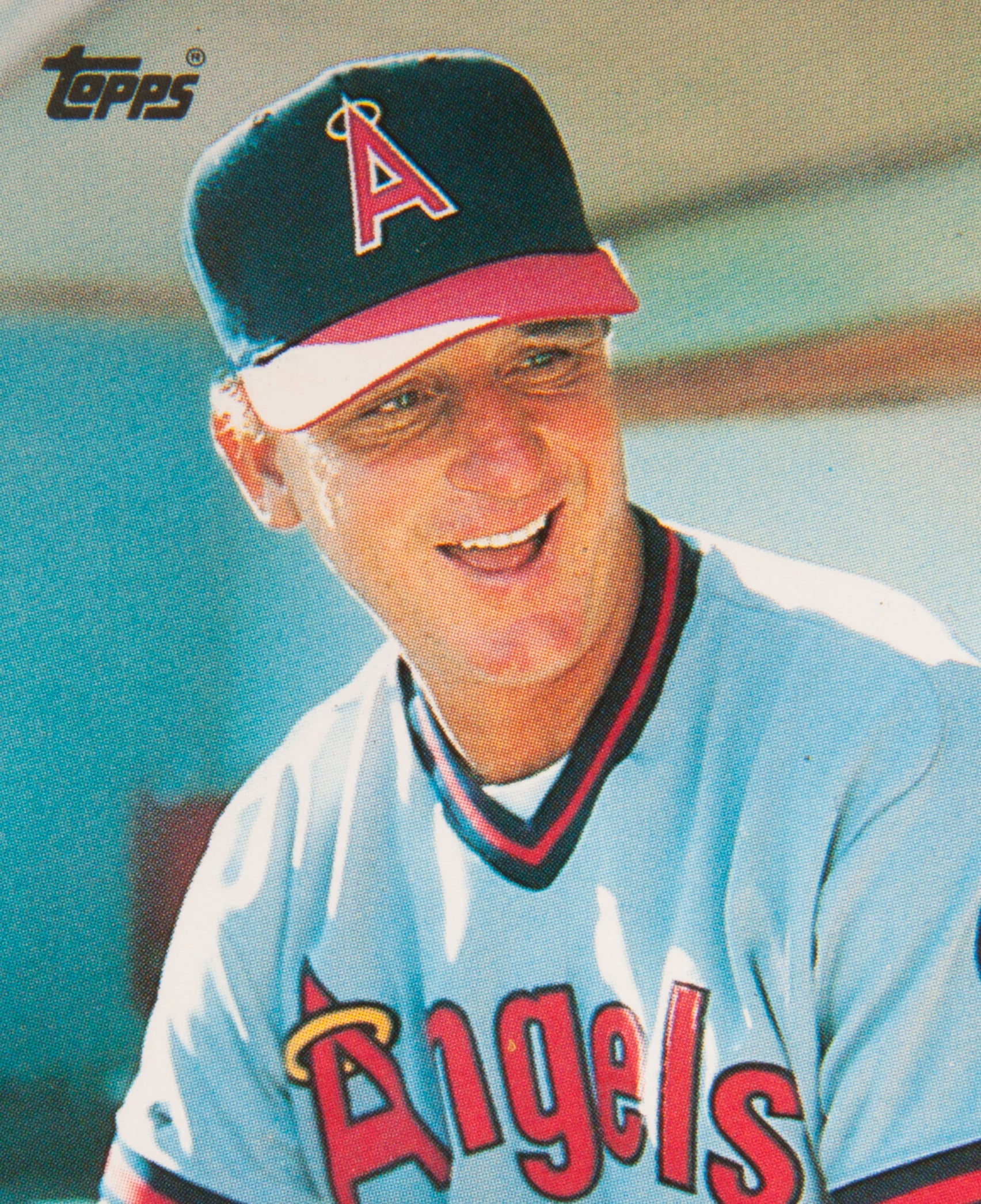

That winter, Stanhouse became a free agent. The Orioles, who tended not to be aggressive in signing their own free agents, watched idly as the Los Angeles Dodgers offered Stanhouse a five-year contract worth just over $2 million. Stan the Man Unusual took the offer.

While the money was great, Stanhouse’s stay in Los Angeles would become nightmarish. In 1980, he pitched in only four games before going down with the first of several arm injuries. He would return to action three months later, but was ineffective. As the season continued, Stanhouse lost his closer’s role to young left-hander Steve Howe.

Injuries to his shoulder and back so affected Stanhouse that the Dodgers released him the following spring. He spent 1981 out of baseball; that fall must have been especially cruel, as he was forced to watch from home while the Dodgers won the World Series.

Stanhouse found work the following spring, after the Orioles invited him to Spring Training. It didn’t take long for Stanhouse to pitch with his usual lack of precision. In his very first spring outing, he allowed a walk and a single and nearly walked another batter before wiggling out of trouble. “I could hear Earl shouting from the dugout when I threw two balls to the first hitter,” Stanhouse told the Sporting News.

In spite of such histrionics, Stanhouse made the team and received a standing ovation in his return to Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. But for the most part, he pitched poorly throughout the summer. With his ERA bloated to 5.40, Stanhouse received his release after the season. In 1983, he attempted a minor league comeback as a player/coach with the Hawaii Islanders, but never made it back to the big leagues.

His playing career over, Stanhouse turned to investment banking, where he became highly successful. He eventually formed his own business, proudly wearing a suit to work each day. Somehow, though, being a button-down businessman doesn’t seem to fit the usual profile of Stanhouse. After all, how many investment bankers have the nickname of Stan the Man Unusual?

In all likelihood, there is just one.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

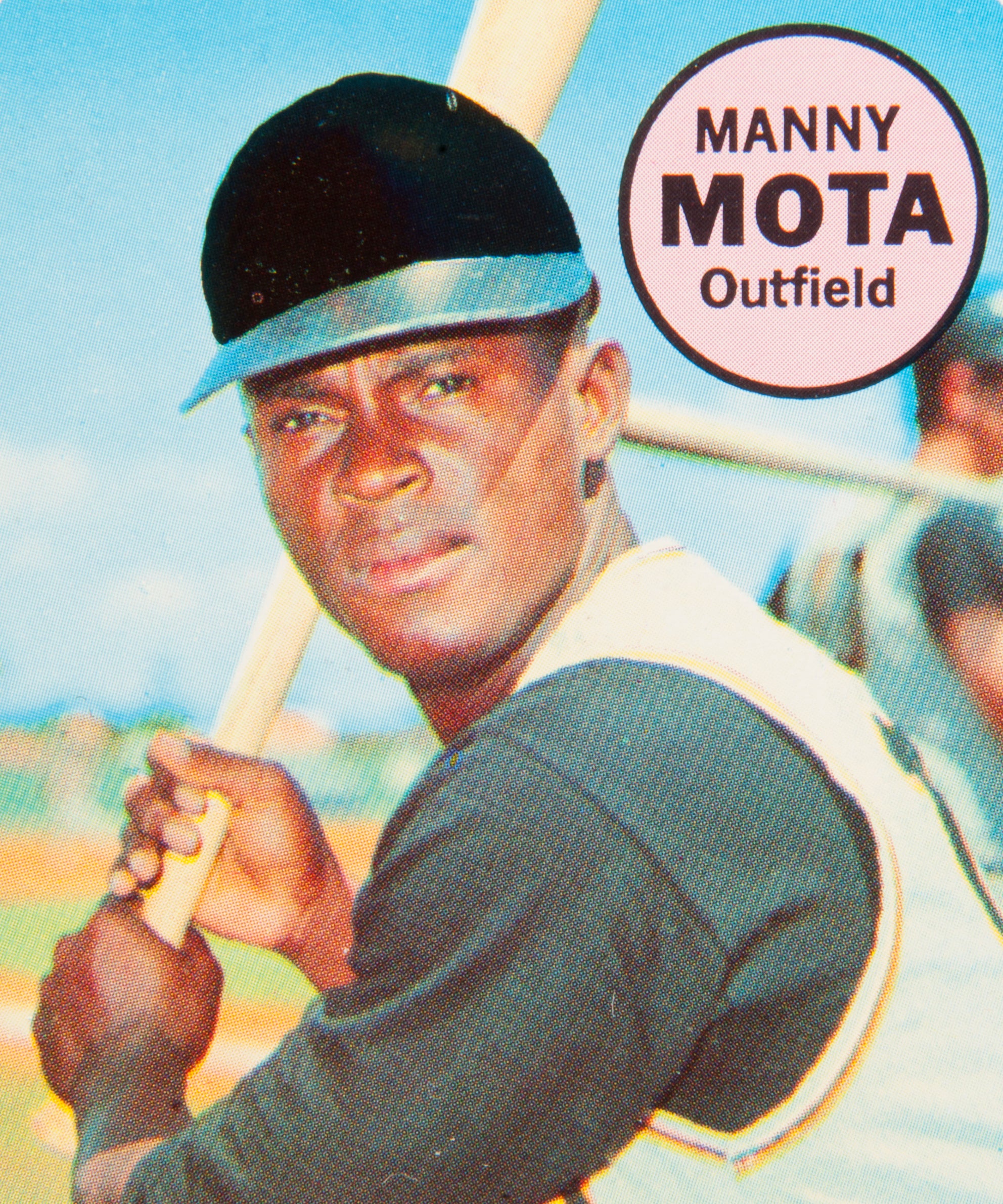

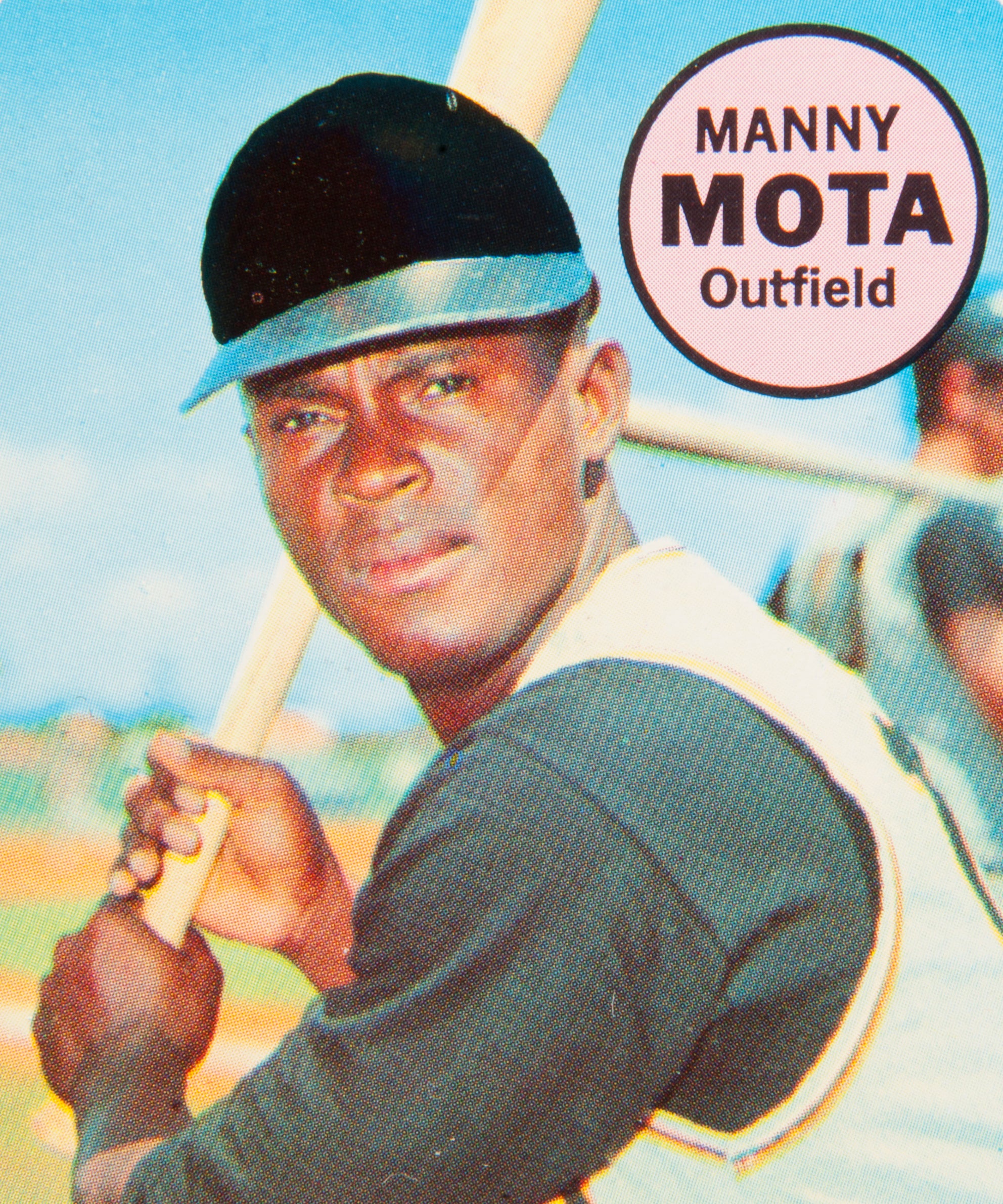

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

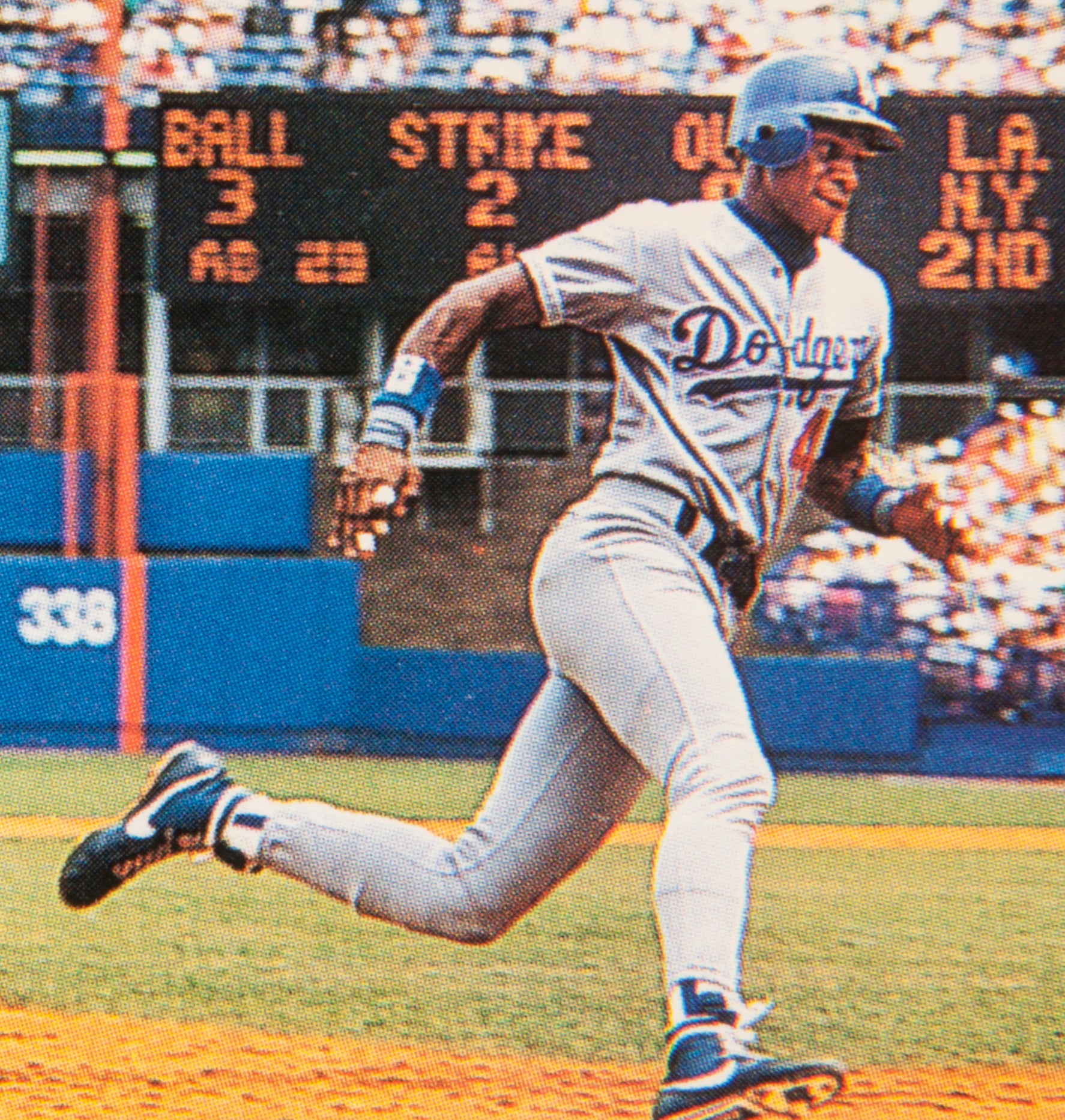

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

Related Stories

Henry Aaron hits home run No. 715

Rogers, I’ve Got Your Number – 8? 6? 7? 5? 3? Oh, 9!

Unforgettable Weekend begins with Classic Clinic

Mrs. America and the AAGPBL

1940 Hall of Fame Game

The Babe of Fenway

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

Dave Winfield signs with hometown Minnesota Twins

Vin Scully came to Cooperstown in 1951

All-Stars Abound Memorial Day Weekend at Baseball Hall of Fame Classic

01.01.2023