- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

One of the funniest movies ever made is the 1980 hit, Airplane!, which made Leslie Nielsen a comedic star and successfully parodied (if not downright mocked) the Airport films that became so popular during the 1970s. The film’s plot has nothing to do with baseball, but the movie does make a short and not so subtle reference to the game. In fact, the movie mentions two ballplayers of some note amidst all of the midair madness.

As troubled pilot Ted Striker (played so well by veteran actor Robert Hays) takes control of the damaged airplane, he tries to concentrate on handling his newfound emergency but starts to hear his own voice in his head. One of Striker’s voices sounds like a public address announcer from a major league ballpark as he makes the following irrelevant announcement. “Now batting for Pedro Borbon… Manny Mota… Mota… Mota.” The strange announcement, which is so random and out of place that it is downright funny, produces a memorable moment of comedy while also demonstrating Striker’s crumbling mental state.

Mota and Borbon were not Hall of Famers, and not even stars really. But they were good players with long careers who carved out enough of a niche that most adult moviegoers would know who they were. Of course, the nitpickers will point out that Mota and Borbon were never teammates in the major leagues, so it would have been impossible for one to pinch-hit for another. (To be totally accurate, Mota and Borbon were teammates in the Dominican Winter League one year, but then why would the Dominican PA announcer have been speaking in English?) Perhaps the fact checkers for Airplane did not do their homework. Or more likely, they considered the small factual error irrelevant in a film that did not take itself seriously. Or perhaps they made the mistake intentionally, for effect. None of that should matter. What should matter is that Mota and Borbon were good enough to take their place in popular culture.

Borbon was a durable relief pitcher and colorful character who was nicknamed “Dracula” and claimed “rooster fighting” as one of his hobbies. A key member of Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine” in the mid-1970s, he died from cancer in 2012. Mota, while not as colorful, managed to play 20 seasons over the span of three different decades, first as a platoon player and then as a pinch-hitter extraordinaire. In some ways, the Manny Mota-type of player has disappeared from today’s game. Pinch-hitting has become a lost art, while veteran backup outfielders have become a scarce commodity now that teams carry so few bench players, instead preferring to have seven and eight-man bullpens.

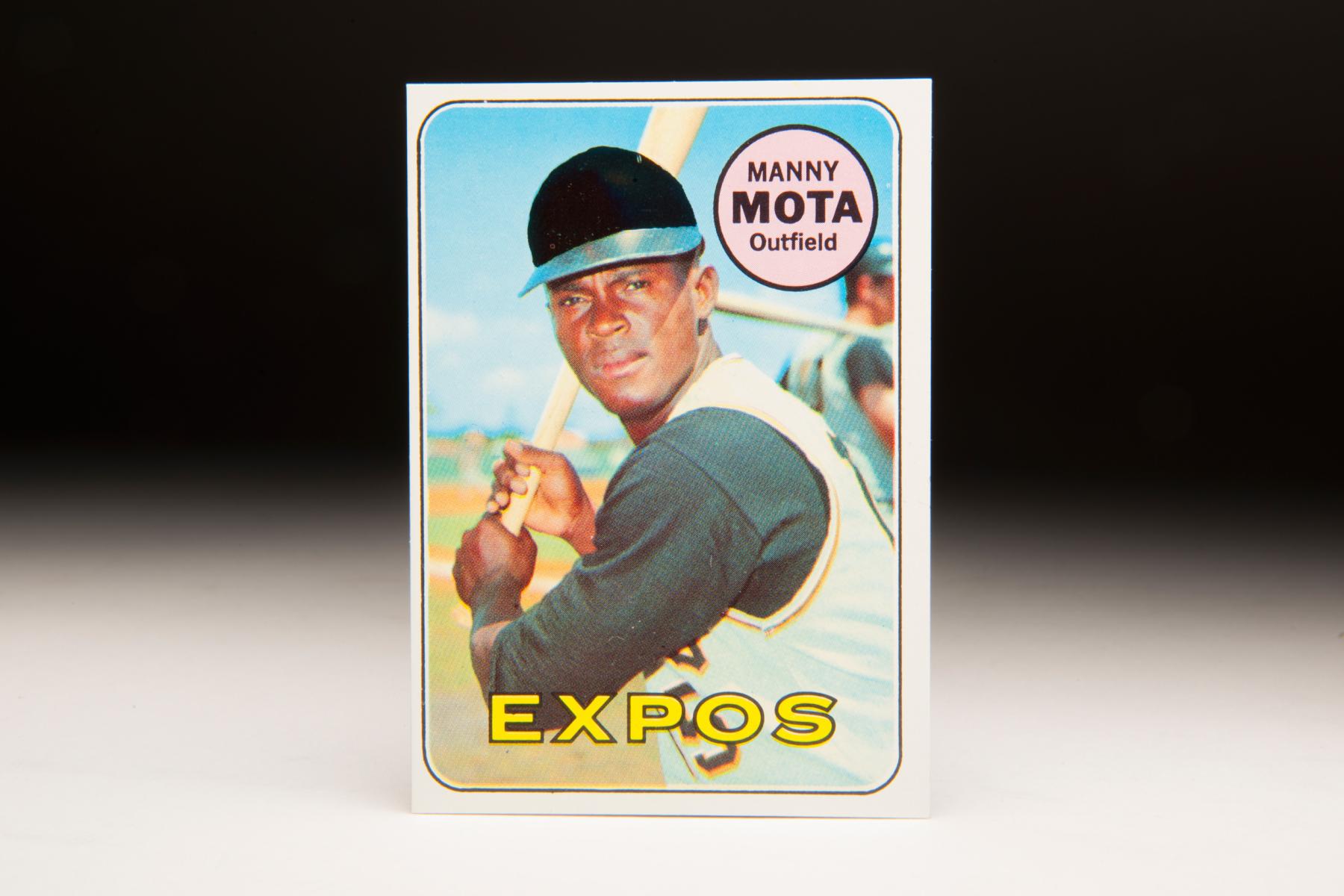

Manny Mota was also part of one of the more interesting baseball cards issued in 1969. By then, Mota was technically property of the expansion Montreal Expos. Like all of the other Expos, he was not shown in his Montreal uniform on his ’69 Topps card. The Expos did not begin their first spring training until February of 1969. In most cases, Topps took photographs of players from the previous season, which would have been 1968. At that point, the Expos did not exist.

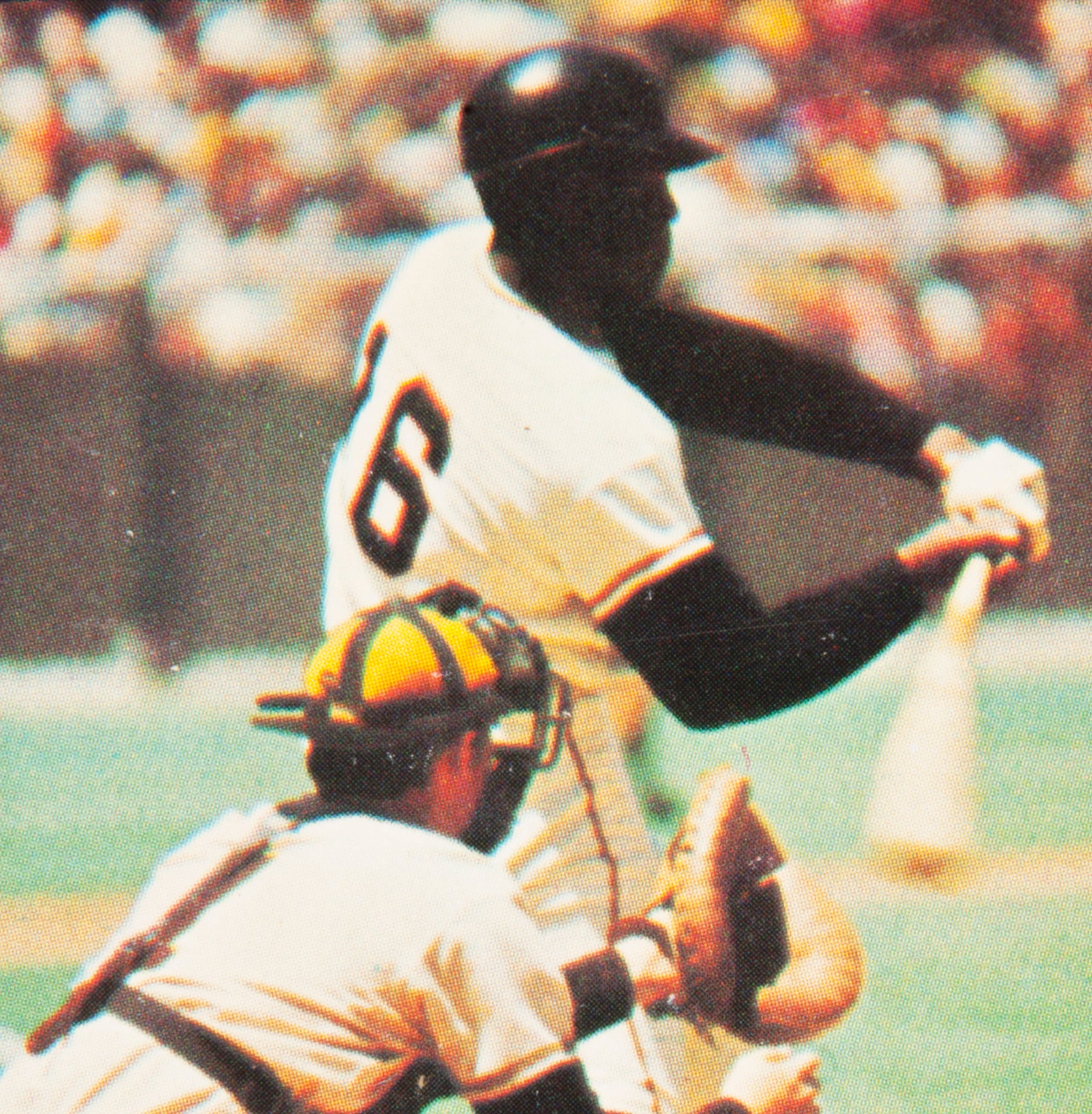

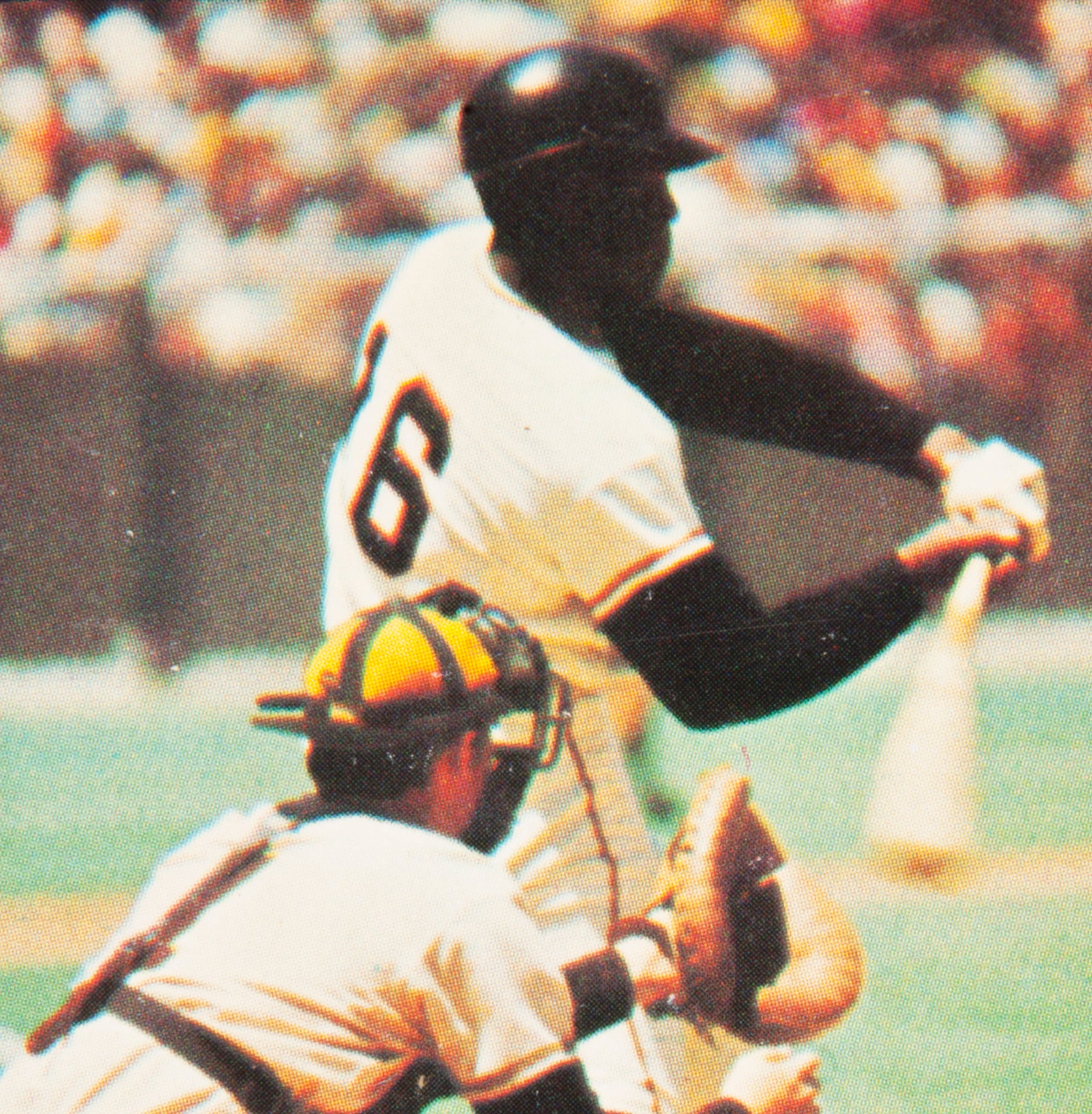

To add to the complications, the Major League Baseball Players Association instructed its members not to pose for Topps photographs during the spring of 1968. This was part of an effort to pressure Topps into increasing its level of compensation to the players. So this photo was not even from the 1968 season; it would have to be from 1967 or even prior to that. Not only did Topps have to resort to showing Mota wearing the uniform of his old team, the Pittsburgh Pirates, but the company also lacked photographs of him without a helmet. So the Pirates’ logo had to be blacked out, giving the helmet a strange logo-less appearance. The black that Topps used in its airbrushing was much darker than the Pirates’ shade of black, giving the helmet an even stranger two-tone appearance. It looks less like a batting helmet and more like a horseback riding helmet used by a jockey.

Signed out of the Dominican Republic as an amateur free agent in the late 1950s, Mota made his major league debut for the San Francisco Giants in 1962. The Giants loved his bat and speed, but they didn’t like his lack of power. They also had a ton of young outfielders in their system. After the season, the Giants dealt Mota to the Houston Colt .45s, a recent expansion team, for infielder Joey Amalfitano. It should have been a one-sided deal for Houston, but Mota would never actually appear in a game for the Colts. Just before Opening Day in 1963, Houston foolishly traded Mota to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Howie Goss.

After starting the season at Triple-A Columbus, Mota earned a midseason call up to Pittsburgh. He platooned with left-handed hitting outfielders Jerry Lynch and Bill Virdon, while also filling in at third base and second base. Mota’s ability to reach base, his defensive skills in the outfield, and his versatility made him a keeper in Pittsburgh.

Mota had virtually no power, but he could hit line drives seemingly at will. By 1966 and ‘67, he became an offensive force, posting averages of .332 and .321, respectively. With most other teams, Mota would have played every day, but he found himself blocked by the talented outfield trio of Willie Stargell, Matty Alou and Roberto Clemente. So Mota made the best of the situation by becoming the game’s best fourth outfielder. Mota benefited from the hitting instruction of manager Harry “The Hat” Walker, who emphasized the importance of hitting line drives and ground balls. Mota also became friendly with Clemente, a veteran player who understood the difficulties that a young Latino faced in trying to make the transition to life in the United States.

The Pirates would have loved to keep Mota in the role of fourth outfielder, but baseball’s expansion blueprint, which called for four new teams in 1969, threw a wrench into their plan. Unable to protect Mota from the expansion draft, the Pirates lost him to the Montreal Expos. The Expos thought so much of Mota that they made the 30-year-old outfielder their first pick in the expansion draft.

Over his first 31 games with the Expos, Mota batted .315. But there were some problems. He did not drive in a single run through his first 97 plate appearances. He continued to show virtually no power. Even more significantly, he was already 31, years from being considered a prospect. For a team looking for young building blocks, a player like Mota didn’t fit.

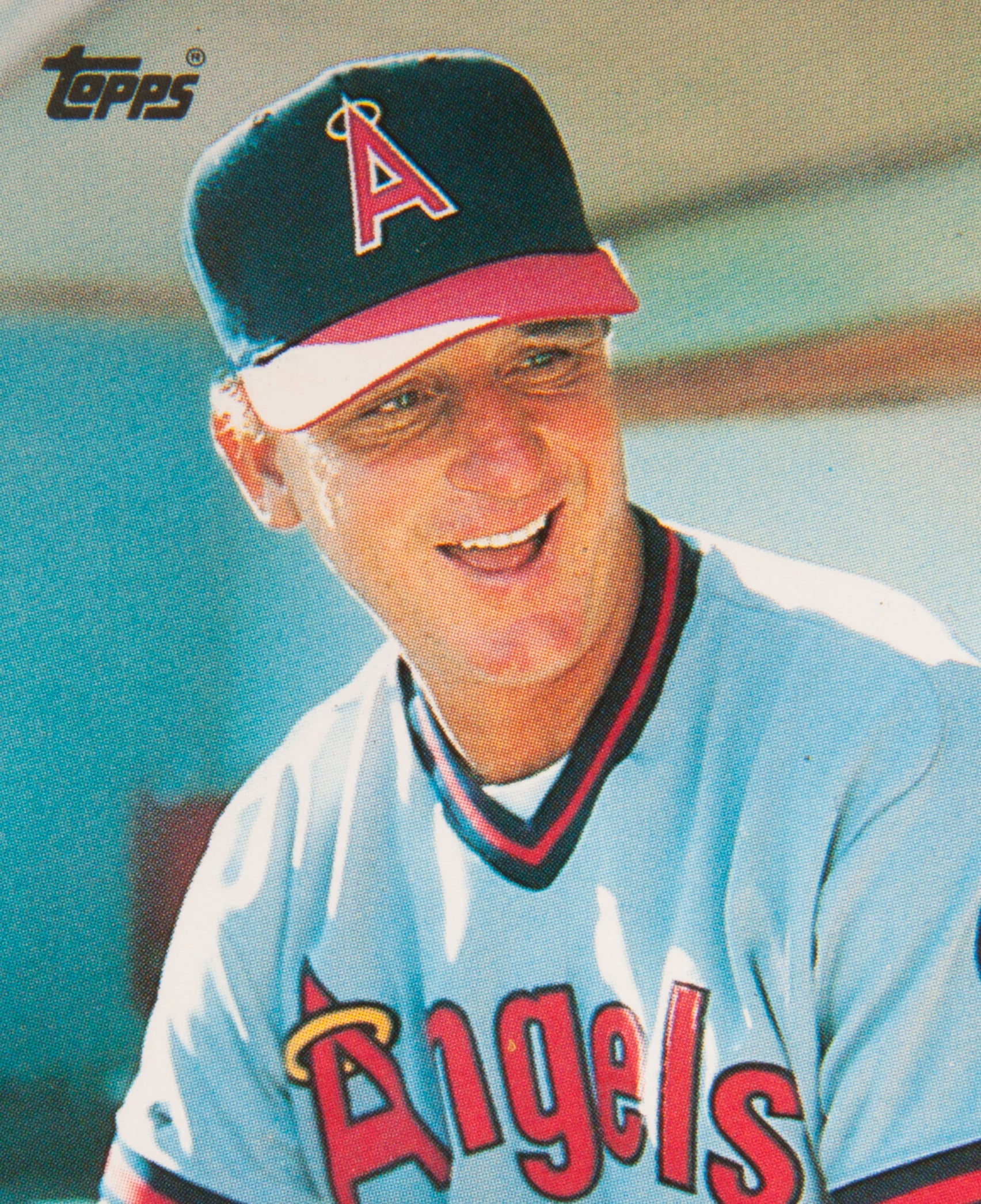

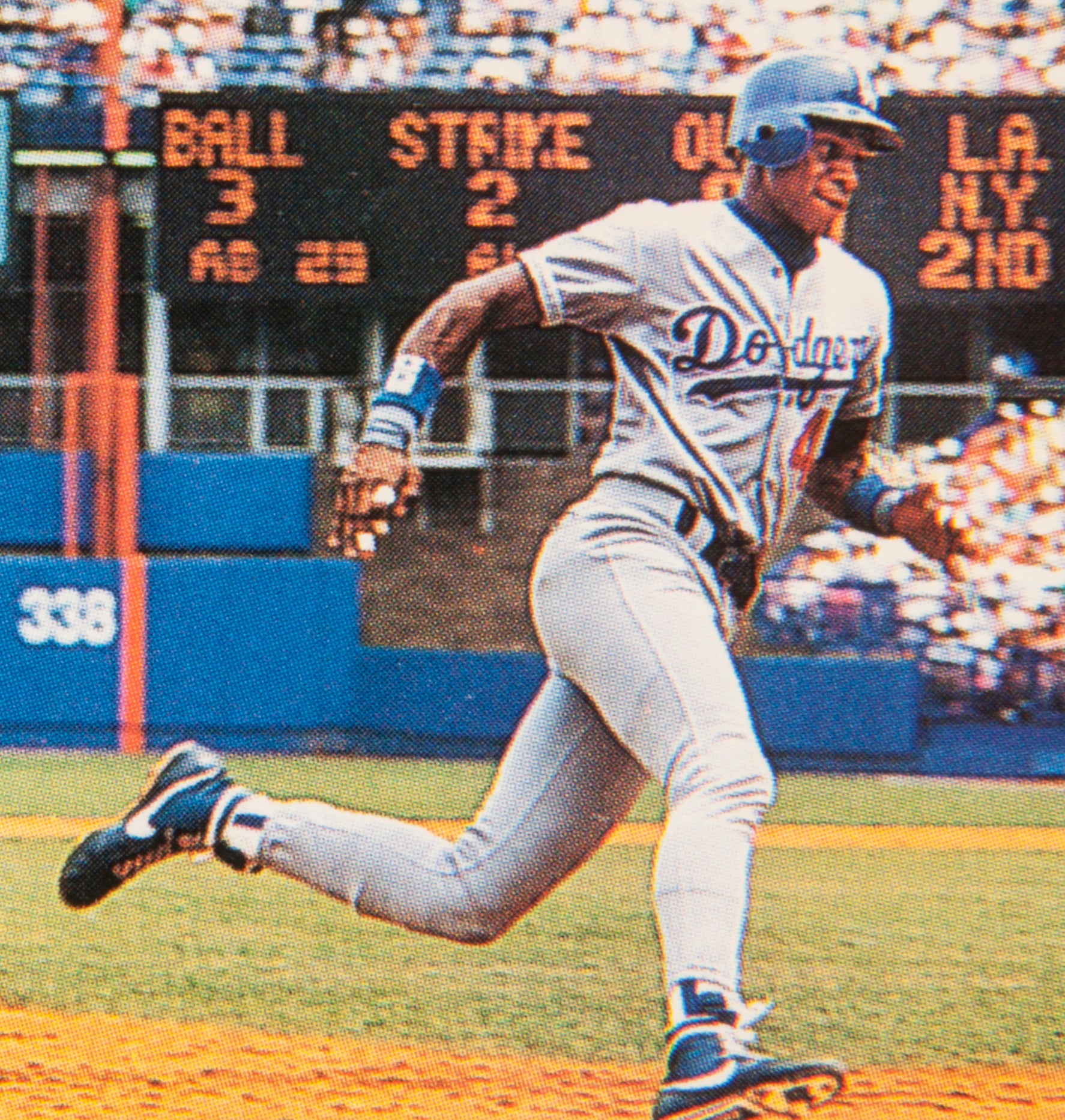

With the June 15 trading deadline fast approaching, the Expos knew they needed to make a move. Only four days before the deadline, the Expos pulled the trigger on a deal, sending Mota and another veteran, Maury Wills, to the Dodgers for first baseman/outfielder Ron Fairly and utility infielder Paul Popovich.

Fairly would give the Expos some power, but Mota would give the Dodgers something more. Mota and the Dodgers began an association that would last the better part of 40 years, including time as a player and coach. During his first four seasons with the Dodgers, Mota hit better than .300 as a platoon outfielder and pinch-hitter.

In 1972, Mota batted .324 in a part-time role and delivered so many key hits that the National League beat writers actually gave him some consideration in the league’s MVP voting. The following year, Mota played so well over the first half that Cincinnati Reds manager Sparky Anderson named him as a backup outfielder on the All-Star team. It would represent the only All-Star selection of his long career.

In 1974, the Dodgers turned toward a youth movement and reduced Mota’s playing time, making him almost exclusively a pinch-hitter. Rather than complain, Mota turned pinch-hitting into an art form. Over a span of six seasons, Mota became the game’s most proficient pinch-hitter, making the most of his small sample of playing time. He batted no lower than .265 during that span of seasons, while turning in averages of .303, .357, and .395.

Mota made the most of his at-bats. In 1977, he accumulated only 50 plate appearances. But in those appearances, he reached base 52 percent of the time and slugged .500. If there were an All-Star game for pinch-hitters, Mota would have been the headlining player.

As a hitter, Mota showed an uncanny ability to put wood on the ball. He rarely swung and missed. He could handle the high pitch better than most. He also showed the ability to take inside fastballs, and inside-out them as line drives into right-center field. Simply put, there was no easy way to get Mota out, even as he aged into his late thirties and early forties.

In 1979, Mota showed little indication of slowing down, as he batted .357 in 42 at-bats. Surprisingly, the Dodgers released him after the season, but did bring him back as their batting coach. Then, in September of 1980, they reactivated him as a player, allowing him to appear in his third decade as a major leaguer. He delivered three hits in seven pinch-hit at-bats, still showing the touch at age 42.

Mota would come to bat one more time (in 1982) before finally calling it quits. With his retirement as a player official, the Dodgers retained him on their coaching staff. In fact, Mota would total 33 seasons as a Dodger coach, the second longest running tenure as a coach with one team, behind only the legendary Nick Altrock. Mota’s upbeat personality played a part in his longevity, allowing him to relate to players from different generations. So too did his ability to communicate in both English and Spanish, giving him an advantage over many other instructors.

Even though Mota is retired from any formal role with the major leagues, he remains active. He and his wife, Margarita, run the Manny Mota International Foundation, an organization that helps underprivileged youngsters and their families in both the United States and the Dominican Republic. The ageless Mota runs free baseball clinics for the kids, continuing his unofficial role as one of the game’s genuine goodwill ambassadors.

Decades after Airplane! added to his fame, Manny Mota is still pinch-hitting for others.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk Featured in Nov. 7 Voices of the Game event as Museum Unveils Whole New Ballgame Exhibit

Henry Aaron hits home run No. 715

Aaron, Robinson elected to Hall of Fame

Hot Corner: Former All-Star Don Wert visits Cooperstown

1946 Hall of Fame Game

Griffey Jr., Piazza elected to Hall of Fame

Mrs. America and the AAGPBL

Vin Scully’s 2016 Dodgers Media Guide puts a 67-year long career into perspective

Nolan Ryan pitches third no-hitter of his career

34th Annual Otesaga Hotel Seniors Open Begins as Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers Tees Up Pro-Am

01.01.2023