- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1989 Topps Doug Rader

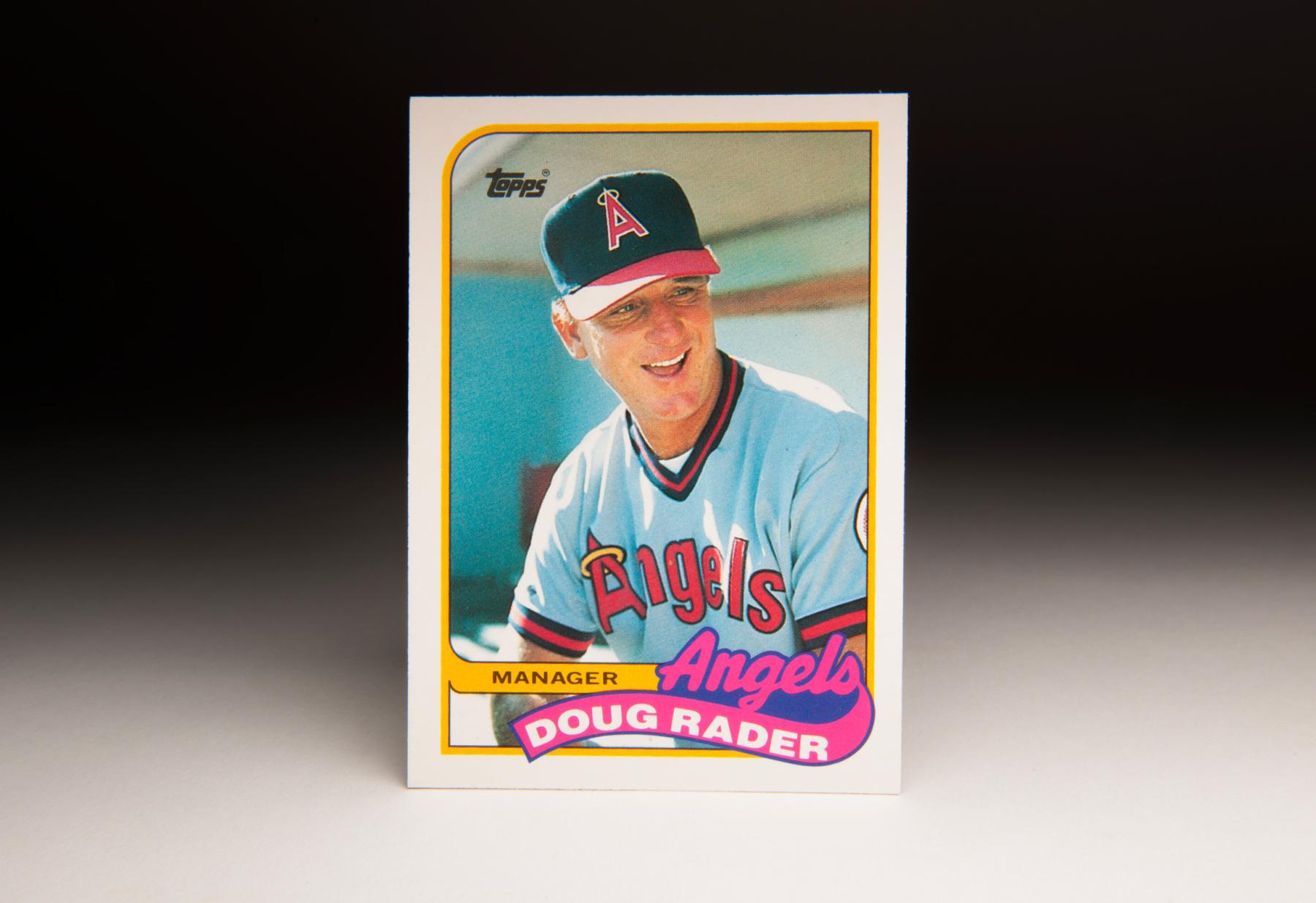

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Doug Rader

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Under ordinary circumstances, managerial cards are not the most thrilling to collect. Who wants to see a card of an older gentleman in his fifties or sixties, usually a retired player, when you can have cards of actual breathing players?

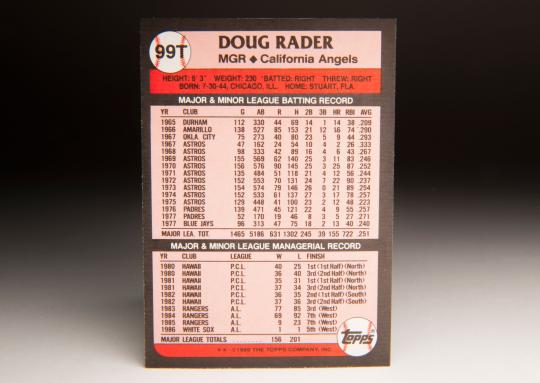

Well, Doug Rader’s 1989 card is not particularly ordinary. First, a check of the back of the card reveals not only Rader’s managerial record, but his statistics as a ballplayer. Rader was a fine player, a Gold Glove-caliber third baseman who hit with some power, particularly in his days with the Houston Astros. When you can hit a significant number of home runs despite playing half of your games in the cavernous Astrodome, you’ve done something notable.

The back of the card also shows us that it is part of Topps’ 1989 Traded set, proving even managers could get the “traded” or updated treatment. The Angels’ manager at the end of 1988, Moose Stubing, replaced the fired Cookie Rojas in the final two weeks of the season and served eight games as interim manager. Unbelievably, Stubing lost all eight games he managed. (Moose never again managed in the major leagues, so he remained without a managerial win - leaving him as the manager with the most losses without a win whose career started after 1900.) During the winter, the Angels announced that Rader had been hired to replace Stubing. Topps had already produced a Stubing card by that point, so the company did not get around to producing a Rader card until it came out with its patented Traded set in the middle of the 1989 season.

The expression on Rader’s face is also not typical of a managerial card. Most managers appear serious, even concerned, or perhaps downright angry (for those who remember Billy Martin’s 1972 Topps card). But Rader was not a prototypical manager. We see him laughing in the California Angels’ dugout, chuckling at the words or actions of some unknown player or coach standing next to him. This could very well have been a photo taken during Spring Training, a time of year when even managers feel more relaxed or at ease. Or, it could have been in the middle of one of the Angels’ regular season road trips. Either way, it’s an appropriate pose for Rader, a man who enjoyed telling and hearing jokes, playing pranks on teammates, making fun of owners, and doing strange things that most managers (or even players) would not dare to do.

Given Rader’s behavior as a player, it’s remarkable that he ever became a manager. Shortly after making his debut with the Houston Astros in 1967, he established himself as the clown of the clubhouse. By 1968, when Nate Colbert joined the Astros, Rader had become a full-blown prankster. “When we were with the Astros, he and one of the guys, another player on the team, went down to the pet store,” Colbert recalled. “That’s when it was legal to own alligators. And they bought three alligators, baby alligators. They waited until we were all in the shower, and they let them loose in the shower, down in Cocoa, Fla. We were trying to climb the walls, these little baby alligators all around us.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The following year, Rader’s on-the-field play caught up to the level of his reputation for hijinks and pranking. A jokester off the field, he played the game with a level of fire and brimstone rarely seen in other players, earning him the nickname of “Red Rooster” (especially fitting because of his curly red hair). Appearing in 155 games, Rader took hold of the third base job, where he played excellent defense, and showed occasional power at the plate with 11 home runs.

Rader played even better in 1970, hitting a career-high 25 home runs and winning the first of five consecutive Gold Glove Awards. Rader’s performance throughout the early 1970s earned him respect across the major leagues. Often overshadowed by third basemen like Brooks Robinson, Ron Santo and Joe Torre, Rader became a second-tier star at the hot corner; he was never quite good enough to make the All-Star team but far better than many players at the position.

The 1970 season also brought additional notoriety in the form of Jim Bouton’s newly published book, Ball Four. The book recounted Bouton’s 1969 season, including his late-season trade to Houston. Bouton wrote extensively about Rader and his penchant for off-color humor and wisecracking. Prior to the publication of the book, most of Rader’s antics had been kept quiet, confined to the Astros’ clubhouse. Bouton’s book outed Rader as one of the game’s biggest characters.

Rader also liked to torment some of his more squeamish teammates. One of them was Astros outfielder Jesus Alou, who was known for having a weak stomach. Rader, who often chewed gum, would wait for Alou to look at him. Immediately removing the gum from his mouth, Rader placed it inside of his nose, nauseating Alou to no end.

In 1974, Rader pulled off one of his most memorable stunts as an offshoot of the famed Ray Kroc public address fiasco. As the Padres were hosting their home opener against Rader’s Astros on April 9, Kroc lost his patience with his young team, which he had just purchased during the off season. The rookie owner stormed into the public address announcer’s booth, seized the microphone and unleashed a brief rant against his players. “I’ve never seen such stupid ballplaying in my life,” Kroc raged into the mic. Padres fans, along with many of the Padres players, and even some of the Astros, were left angry and embarrassed.

After the game, Rader took a few shots at Kroc. “He thinks he’s in a sales convention dealing with a bunch of short order cooks. That’s not the way to go about getting a winner. Somebody ought to sit him down and straighten him out.”

Padres general manager Buzzie Bavasi soon heard about Rader’s remarks, and rather than becoming annoyed with The Rooster, he decided to make a promotion out of the situation. The next time the Astros came to San Diego Stadium, the Padres hosted “Short Order Cooks Night” at the ballpark. Bavasi stipulated that any fans coming to the ballpark wearing a chef’s hat would receive free admission to the ballpark.

As the Astros’ captain, Rader decided to add his own personal touch to the promotion. “Doug Rader… loosened it up by going out and exchanging lineup cards while wearing some kind of chef hat on or an apron or something,” said Johnny Grubb, an outfielder with the Padres at the time. “He kind of loosened the atmosphere and made it a little bit looser in the clubhouse.” Rader added a spatula and a skillet to his ensemble, allowing the lineup card to slip off the skillet into the umpire’s hands.

Rader’s antics were well received in San Diego, and perhaps played a role in a future transaction. After a down season with Houston in 1975, caused partially by the pounding that his feet took on the Astrodome turf, the Astros decided to make Rader available in a trade. They received an inquiry from Bavasi, who was looking for a veteran third baseman to shore up San Diego’s infield defense. Bavasi surrendered two young right-handed pitchers, Larry Hardy and Joe McIntosh, in a deal for Rader.

Still only 31 years old, Rader became San Diego’s everyday third baseman. He also managed to quit smoking, a habit that had plagued him throughout his playing career. He played well for a season and a half with the Padres, but with the team floundering near the cellar in the National League West, he again became trade bait. In the middle of 1977, the Padres traded him to the expansion Toronto Blue Jays, who were looking for a veteran right-handed batter to handle the DH role.

Rader hit well for the Blue Jays over the balance of the season, but became victim to Toronto’s youth movement in the spring of 1978. Released late in the spring, Rader was out of work. Unable to find a job elsewhere, he called it quits.

Not wanting to leave the game, Rader turned to minor league managing, accepting an offer to skipper the Padres’ Triple-A affiliate, the Hawaii Islanders. The decision surprised some, given Rader’s predilection for playing pranks and taking on the role of class clown. But those antics masked an intelligence along with a burning desire to win.

By the winter of 1982, Rader found himself back in the big leagues - as the newly appointed manager of the Texas Rangers. At his opening press conference, he admitted that the new job “scares the hell out of me.”

Rader would manage the Rangers for two and a half years, but without much success. A 9-23 start to the 1985 season doomed him, along with a clubhouse full of bickering players, resulted in his firing. He then joined the Chicago White Sox as a coach, briefly managing them on an interim basis, before finding work as the Angels’ manager prior to 1989. Rader’s first season in California went beautifully; he guided the team to a surprising record of 91-71 and a respectable third-place finish in the American League West.

Unfortunately, Rader could not sustain the success. The Angels dipped below .500 in 1990. When they continued to hover near the break-even mark in 1991, the Angels fired him in midseason, replacing him with Buck Rodgers.

Though he was only 46 years old, Rader would never manage again. He did become the first hitting coach in the history of the Florida Marlins, but decided to step down only two seasons later and announced his retirement from the game.

As a manager, Rader never fulfilled the expectations that some had created for him. Noted baseball writer Bill James once wrote that Rader had all of the requisite abilities to be a great manager - toughness, knowledge of the game, and a sense of humor - but his managerial record never reflected those attributes.

Some critics say that Rader was too much of a jokester to be a great manager. I tend to doubt that. More likely, he just didn’t have the talent in Texas or California, and didn’t have the fortune of managing any teams that had realistic goals of being a championship contender.

Whatever the reason, Rader’s managerial career should not be regarded as too much of a blemish on his career. He was a fine player and a man who seemingly had a ball playing the game, all while treating his teammates to a memorable sideshow. The game is meant to be fun; Rader and his mates sure had fun along the way.

Baseball needs more people like Doug Rader - not fewer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

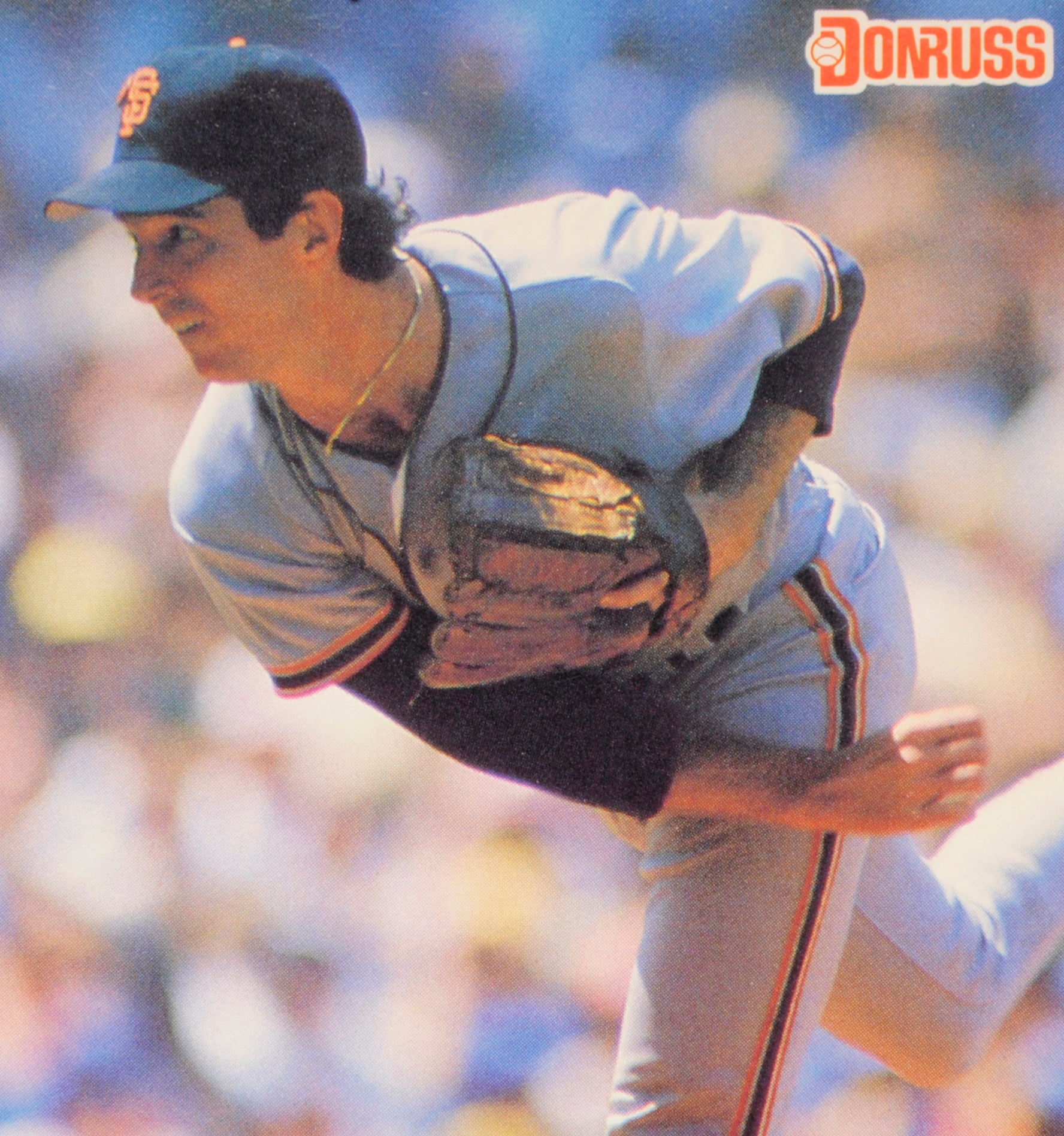

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Kaat

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Kaat

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

1968 Hall of Fame Game

Wade Boggs, Ryne Sandberg elected to Hall of Fame by BBWAA

#ShortStops: The Sultan of Southpaw Shutouts

The Wizard thrills fans as Hall of Fame Weekend begins with PLAY Ball

Baseball Writers’ Association of America 2016 Hall of Fame Ballot Announced

Rare Christy Mathewson bat added to Hall of Fame collection

53 Hall of Famers Scheduled to Return to Cooperstown for July 24-27 Hall of Fame Weekend

01.01.2023