Why did the major leagues ignore the light-skinned Cuban, during a period when Latins Dolf Luque, Mike González, and Armando Marsans all went to the big time? He was a little lighter than I am, but he had real rough hair.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Cristóbal Torriente Bests the Bambino

#GoingDeep: Cristóbal Torriente Bests the Bambino

He was widely known as a franchise-type player, the sort of singular talent who could lead a team to victory in a myriad of ways. A powerfully built outfielder with a left-handed bat that could reach any fence in any park, he had a flare for the extravagant and for racking up mind-boggling statistics.

He was as iconic as he was unforgettable.

“A tremendous guy. Big left-handed hitter, played the outfield,” Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch once said of him.

“He did everything well, he fielded like a natural, threw in perfect form, he covered as much field as could be covered,” said his former teammate, Martín Dihigo. “As for batting, he went [from] being good to being something extraordinary.”

The sports editors of the Pittsburgh Courier called him a “prodigious hitter, a rifle-armed thrower, and a tower of strength on the defense.”

Babe Ruth? Mel Ott? No.

His name was Cristóbal Torriente.

Torriente, a hard-hitting center fielder who heralded from Cienfuegos, Cuba, was one of the first Cuban baseball stars to play in the United States. A founding member of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame’s first class of 1939, Torriente was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, by a Special Committee on the Negro Leagues.

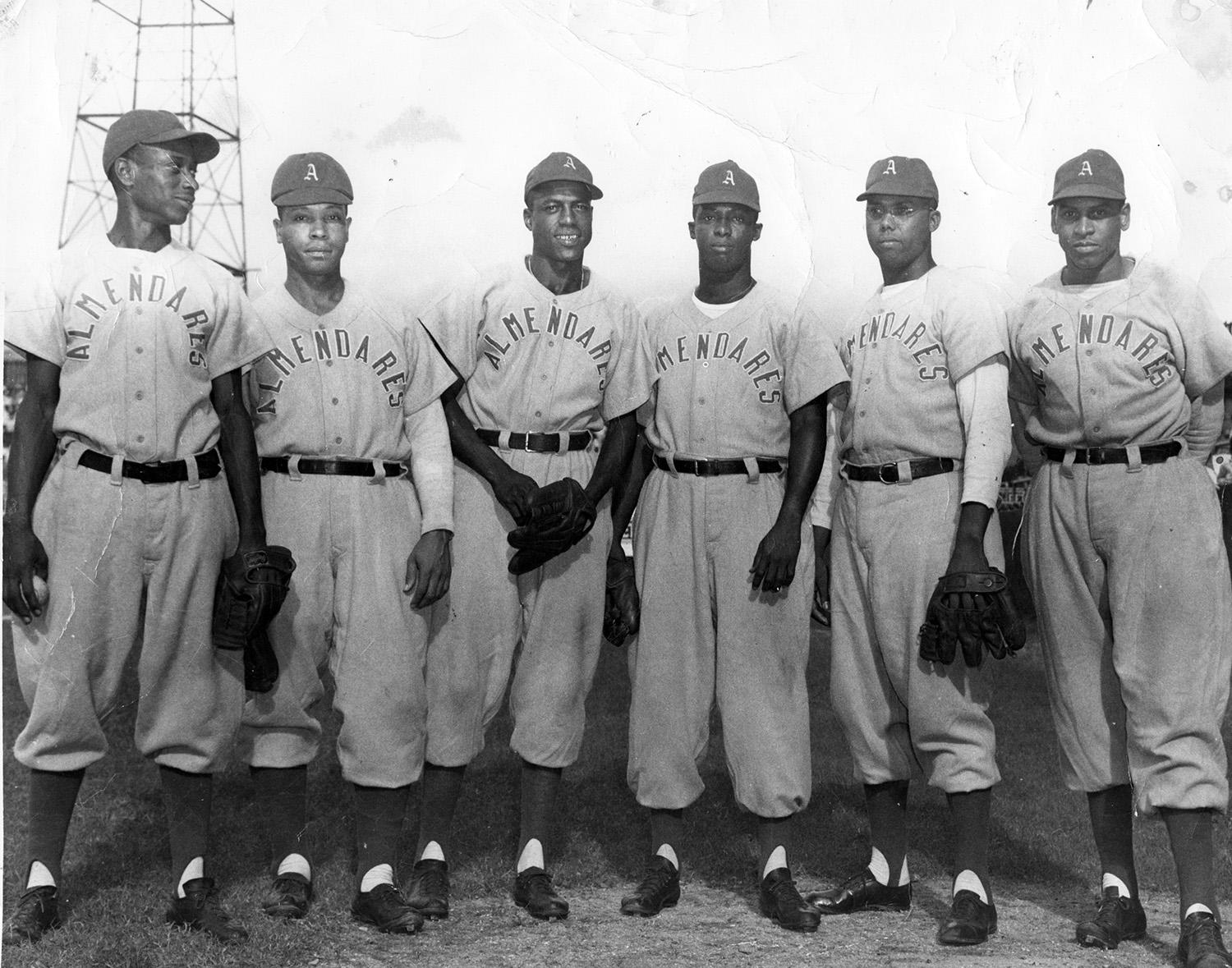

For a player who was proclaimed to be the “Babe Ruth of Cuba,” his fame would only go as far as the Negro Leagues – until the Great Bambino himself came to Torriente’s homeland, under the promise of $1,000 per exhibition game, to play against the Havana Reds and Cristóbal’s Almendares Blues. In a game which has gone down in Cuban baseball lore as a David and Goliath story of sorts, Torriente upstaged Ruth on his home soil, bursting onto the baseball scene and capturing the attention of fans worldwide.

But years before Ruth ever set foot in Cuba, Torriente was rapidly developing as a coveted young player. While there isn’t much in the written record about Torriente’s baseball upbringing, it is widely believed that he started playing at an early age for the sugar mill baseball teams in the Cienfuegos area.

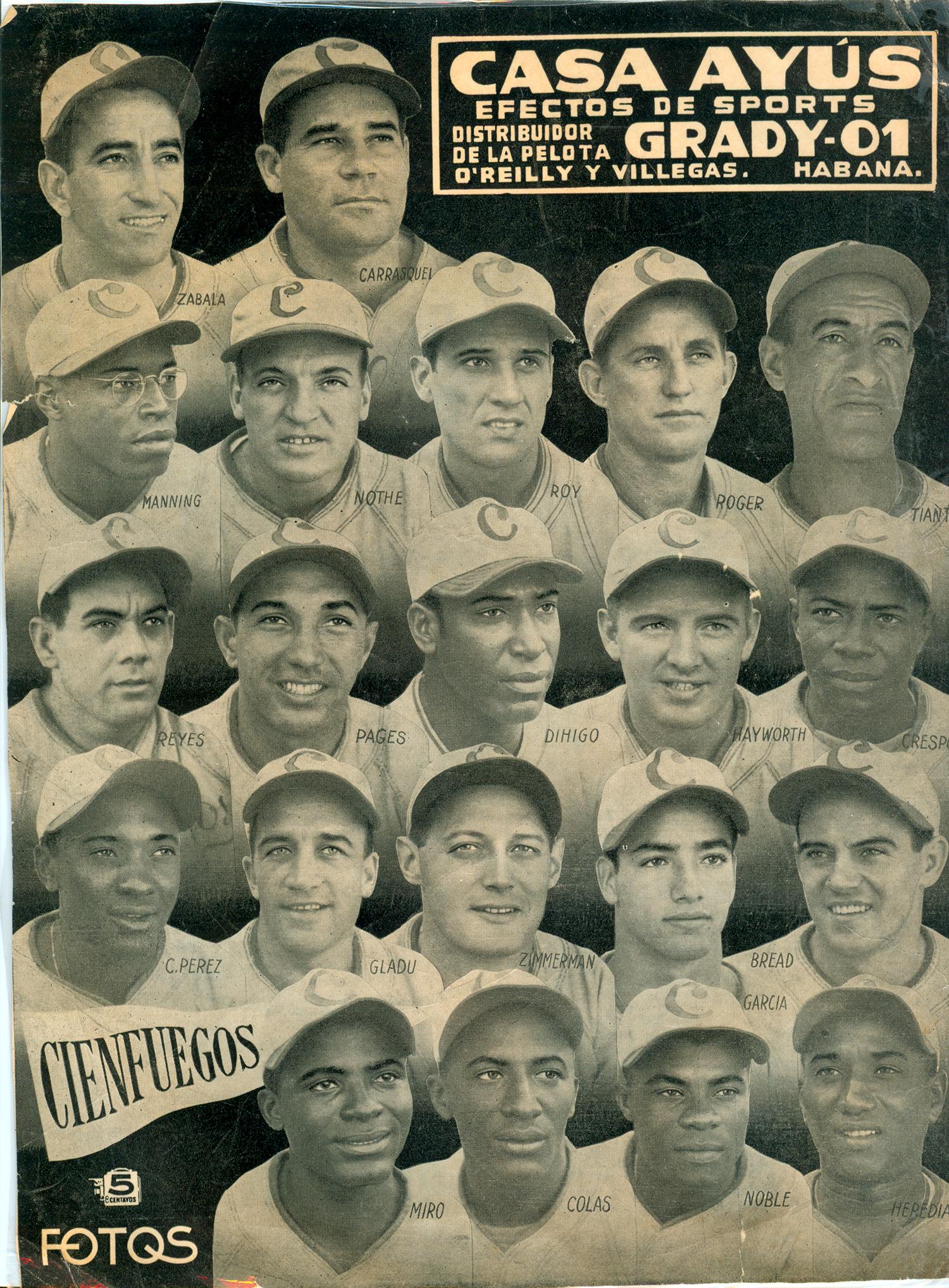

Cristóbal Torriente heralded from the town of Cienfuegos, which was famous for breeding future baseball stars. Cienfuegos was a sugar mill town and had teams associated with the mills which would compete against each other. Above is an advertisement for one of those teams, now in the Hall of Fame's collection. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

“The important thing about the Cienfuegos area, was that the sugar industry was made for baseball,” explained Roberto González Echevarría, a professor of Hispanic and Comparative Literature at Yale University, and author of The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. “The sugar mills developed smaller company towns, and these small company towns around the sugar mills had baseball teams that competed against each other. He probably got his start there. Cuban blacks could only get their start in sugar league baseball and in the amateur leagues.”

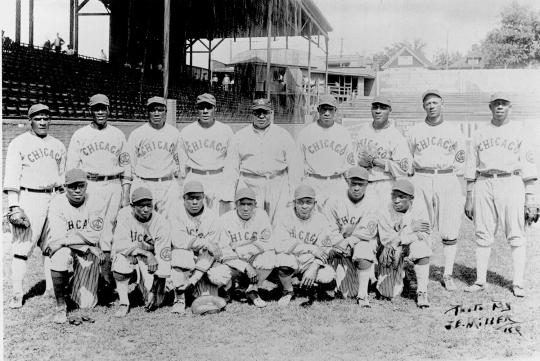

After his tenure in Cienfuegos, Torriente would begin his pro career with the Cuban Stars, in 1913. He'd play for them until 1916, when he briefly joined the Kansas City Monarchs. His career took off soon after that, when he began playing under Hall of Fame manager Rube Foster with the Chicago American Giants – the powerhouse of the Negro National League. Torriente was so highly touted and anticipated that fellow Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston was relocated from center field to left upon the Cuban’s arrival. The "Babe Ruth of Cuba" would help the Giants capture their first three Negro National League pennants, from 1920 to 1922.

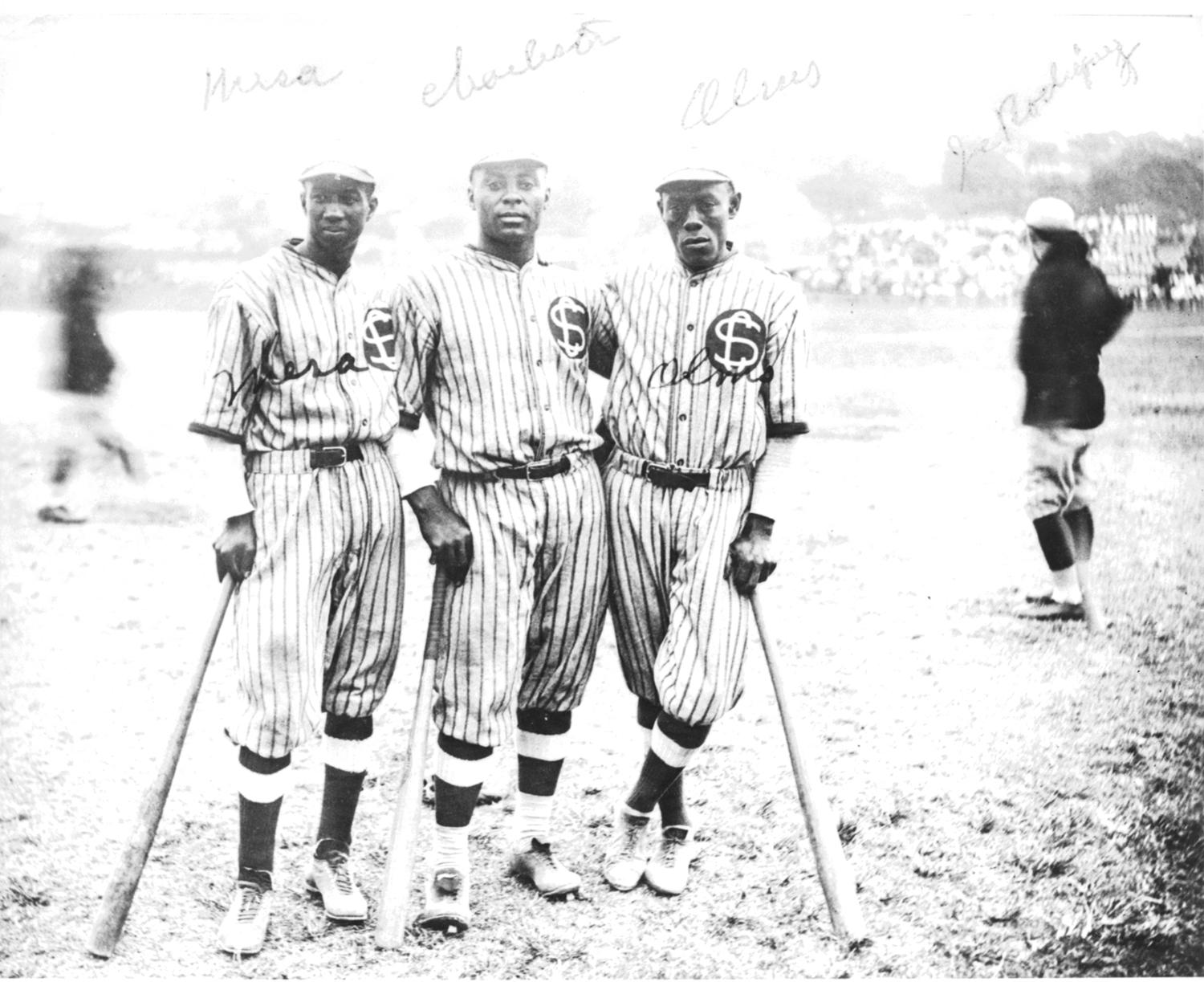

It was common for players to travel to Cuba to play winter ball with various teams, including the Cuban Stars, with whom Cristóbal Torriente began his baseball career with in 1913. Pictured above, are Pablo Mesa, Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston and Alejandro Olms, at Almendares Park in Havana. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

During his 17 seasons in the Negro Leagues, Torriente moved around quite a bit, as was characteristic of the time. After his six year stint with the Chicago American Giants, he returned for another year with the Kansas City Monarchs, a year with the Detroit Stars, and a year with the Cleveland Cubs. During that span, he compiled a .331 batting average, and hit as high as .432 in 1920 – the year in which he won the league’s batting title. Stacked up against other Negro Leaguers, he ranks 11th all-time in RBI with 309, 12th in slugging percentage with .517 and 16th in total bases, with 1,055.

He could even perform on the mound, posting a pitching record of 16-5 during his career in the Negro Leagues.

“Torriente batted cleanup for Rube [Foster] through 1925, but he was much more than a power hitter,” an unnamed scout in the Ashland Collection wrote. “Unlike Louis Santop, Mule Suttles, and Heavy Johnson, all top sluggers of that era, Torriente was also a master at bunting, base running and defense.”

A five-tool player, Torriente could dominate the game with his bat, his arm, his legs and his glove, but was unfortunately playing at the wrong time. Prejudices of the era were alive and well, and prevented the Afro-Cuban Torriente from advancing to the big leagues, even though other white Cubans of the time,did.

“Why did the major leagues ignore the light-skinned Cuban, during a period when Latins Dolf Luque, Mike González, and Armando Marsans all went to the big time?” a scout named “Gardner” hypothetically asked in a report from the Ashland Collection. “He would have went up there, but he had real bad hair. He was a little lighter than I am, but he had real rough hair. He would have been alright if his hair had been better.”

It meant that a man who had drawn comparisons to Ruth and other standout talents was relegated to the Negro Leagues for the entirety of his career – a fact that made a 17-day stretch in the fall of 1920 perhaps the most memorable time in his career.

That fall, the New York Giants played a series of exhibition games against the Havana Reds and the Almendares Blues. The brainchild of the ever-economical mind of Abel Linares, the owner of Almendares, the games were a huge attraction in baseball-crazed Cuba. Torriente, playing winter ball for the Blues at the time, had a chance to play against the Babe.

While Ruth wasn’t a member of the New York Giants, he was interested in making an ‘easy’ $20,000. And Linares was interested in drawing a big crowd.

“Linares searched his mind for the most compelling (way) to promote an exhibition that a year earlier had been reduced to second billing by a soccer match that received special attention because it was supported financially by Spain,” says Yuyo Ruíz in The Bambino Visits Cuba. “The soccer match was held in the afternoon, while Linares was forced to stage his exhibition in the morning. To make up for that, Linares, who had developed a knack for giving Cuban fans what they wanted, knew he had to do something special. So he approached the game’s biggest star, George Herman “Babe” Ruth, and ultimately convinced him to come to Cuba.”

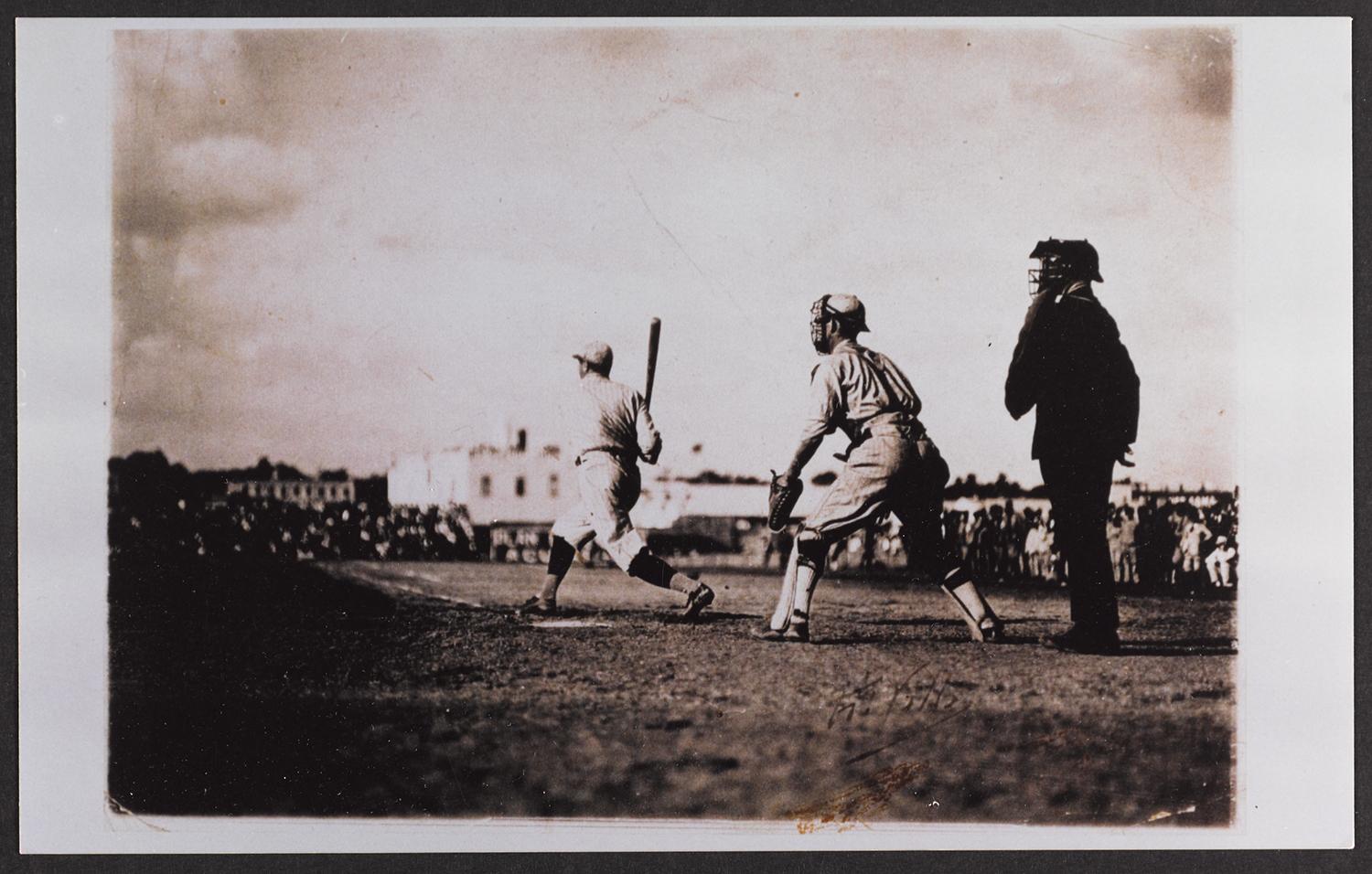

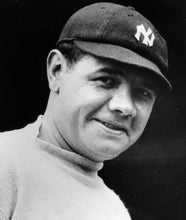

One of the many images in the Museum's collection depicts Babe Ruth batting in Havana, Cuba, at the same exhibition game Torriente played in on Nov. 6, 1920.

However, Ruth didn’t travel alone. Lured by the money Linares was offering, the New York Giants went down to Cuba in mid-October, led by manager John McGraw and then assistant manager Johnny Evers. While the entire team didn’t make the trek – the Giants were quite short on starting pitching, a factor which would not play out in their favor when facing Torriente, in particular – about a dozen of them did. Ruth would arrive in late October, accompanied by his then-wife Helen, and would stay for a number of weeks.

Already an iconic player who had just come off of a historic 54-home run season, Ruth’s arrival was proclaimed far and wide, in both American and Cuban newspapers.

He did everything well, he fielded like a natural, threw in perfect form, he covered as much field as could be covered. As for batting, he went [from] being good to being something extraordinary.

“Babe Ruth is playing winter ball in Cuba,” read the Daily Illinois. “Reports have it that boats going from the U.S. to Havana are putting on armor plates to escape being torpedoed by stray homers.”

“[Ruth’s] feats were touted in the papers,” González Echevarría said. “But Cuban baseball was not home run centered. Black baseball was very prudent, very tactical. At this time, Cuba was enjoying an economic bonanza because of the post-World War I period, and the prices of sugar had gone up. And so, they could afford for an American team to come and play.”

Because Cuban baseball was more driven by small-ball style of play, bombastic hitters like Babe Ruth and Cristóbal Torriente were exciting and different. Expecting to see a show, people paid high ticket prices set by Linares – high enough to pay off the $20,000 that would eventually make its way into Ruth’s pocket.

With high standards awaiting him, Ruth arrived at Almendares Park on Oct. 31, to play in his first exhibition game of the tour. He singled and tripled, but hit no home runs. Varying newspaper accounts from the time list his home run total as somewhere between zero and three during his time in Havana, a disappointment for fans who had expected to see the home run king.

But the real shock came on Nov. 6, Ruth’s third game on Torriente’s turf. Because the roster was limited, John McGraw opted to put in George “High-Pockets” Kelly as a starting pitcher, even though Kelly traditionally played first base. Cristóbal reportedly smacked a two-run homer to left-center field, and came back for more in the third with another solo round tripper.

“I was down in Havana in 1920 with Babe Ruth and about 12 of the New York Giants,” Frankie Frisch recalled. “That’s over 50 years ago, but I can still recall Torriente. I think I was playing third base at that time, and he hit a ground ball by me, and you know that’s one of those things – look in the glove, it might be there. But it wasn’t in my glove. It dug a hole about a foot deep on its way to left field. And I’m glad I wasn’t in front of it!”

El Día newspaper, based out of Cuba, confirmed this account, with a prideful one of their own.

“Yesterday Cristóbal Torriente elevated himself to the greatest heights of glory and popularity,” the editors wrote of their new-found hero. “His hitting will enter Cuban baseball history as one of its most brilliant pages. Almendares' potent weapon is responsible for the fame that Cuba fans now share and who now better understand his ability to hit a baseball.”

And for all of the praise Torriente received, Ruth was receiving criticism for not living up to his end of the bargain.

The Evening World published a story entitled “Babe Ruth Returns Here From Almost Homerunless Junket on Cuban Soil”, explaining that “the funny part of the trip to Cuba was that Babe was not able to live right up to the handle of his reputation as a home run hitter. Down there, natives were led to believe that Babe could knock out a homer whenever he wanted to, but three home runs during the entire stay in Cuba was all that was accomplished.”

A couple of weeks later, the same paper took it one step further, singling Torriente out as well. “[Babe Ruth] didn’t make a single home run in the fifteen games, though he batted .500 on the trip. Torriente, the ”Black Babe Ruth” on the other hand, hit three home runs in one game last week, and in a fourth trip to the plate made a two-bagger.”

According to the Cuban newspaper El Diario de la Marina, fans started to boo Ruth when he stepped up to the plate, frustrated that they weren’t getting what they had originally paid to see.

By the fifth inning, the Bambino decided to take matters into his own hands, and stepped onto the mound. In a dramatic match-up between a world-famous slugger and a rising star, Torriente drilled a line drive to left field for a two-run double. He would finish the game with three home runs and six RBI in five at-bats, while Ruth would go hitless.

Although the New York Giants would narrowly defeat the Almendares Blues in the series, 5-games-to-4, the Blues would take that game in an 11-4 win, led by the offensive prowess of their own Bambino.

Feeling pride in their hometown hero, the Cuban fans threw money onto the field for Torriente, as a way of showing their admiration. Some, newspapers reported, even went as far as throwing cigars and gold watches. But what Torriente received in money that day was far exceeded by the high compliments he would earn from all who had witnessed the game.

Regardless of what the media was printing and how the fans were reacting, Torriente insisted his feat was small when sized up against those of the Great Bambino.

“In summary, Torriente recovered quite a bit of change and 300 cigars,” reported the Cuban newspaper Horacio Roqueta. “Interviewed by journalists over his three home run performance, he said it was purely an accident: ‘Ask the Bambino what he does every day.’”

While these sensationalized newspaper articles gave varying descriptions of the game, a similar message seemed to ring true in most accounts – Cuba had found its Bambino, a hard-hitting slugger that it could tout as its own. Yet it’s important to note that today’s historians have presented conflicting opinions on the level of competition during these games.

Echevarría, for instance, is of the mindset that this almost-mythical performance by Torriente could be accounted for by a number of factors, like the dearth of starting pitchers the Giants had to choose from.

“It became an iconic game, although it was really not a serious game,” explained Echevarría in a phone interview. “It was an exhibition game. And so the Cubans wanted to best the Americans at anything they could, and were very proud of the fact that [Torriente] had bested Babe Ruth.”

Even El Diario de La Marina questioned the legitimacy of the game, comparing it to batting practice -- “resulto una practica al bate del club almendares” – and implying that certain players might have been drunk during the game.

Jorge S. Figueredo, a historian who specializes in Cuban baseball, insists in his brief essay November 4, 1920: The Day Torriente Outclassed Ruth, that the myth is not only true but was an important part of Cuban history. “…he had the most unforgettable game of his career and surely one of the most memorable games in the history of Cuban baseball as he outclassed the incomparable Babe Ruth.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Competition level aside, it was clear that by the end of his time in Cuba, the Bambino was ready to get back to his normal self.

The day after he returned to the United States, the Tulsa Daily World published a photo of Ruth grinning, with a caption below it which read “Mr. George Ruth, known in ball-dom as Babe or the Bambino, returned yesterday from Cuba, radiating ambition and declaring he will establish a mark of 75 home runs next season.”

Whether or not Torriente’s acclaimed performance ignited a competitive spark in Ruth is up for debate. But what can’t be denied is the lasting impact Torriente’s performance would have on Cuban history.

In the image of Ruth in the Hall of Fame’s Digital Archive Project, he is captured mid-swing. Although the background of the photo is blurry, the enormous dimensions of Almendares Park, lined with palm trees in the background to give it a tropical flair, are visible. As Ruth swings, it seems as if every spectator in the park is as still as the photo itself. Time is put on hold, as the world waits to see the Bambino they have heard about from far and wide.

Cristóbal Torriente, of course, did not have the fabled career that Babe Ruth did, as segregation-era baseball sadly did not make that an option. But for at least one game, he upstaged the great Bambino and gave a glimpse, amid the palm trees surrounding Almendares Park, of the power and talent that would one day make him a Hall of Famer.

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

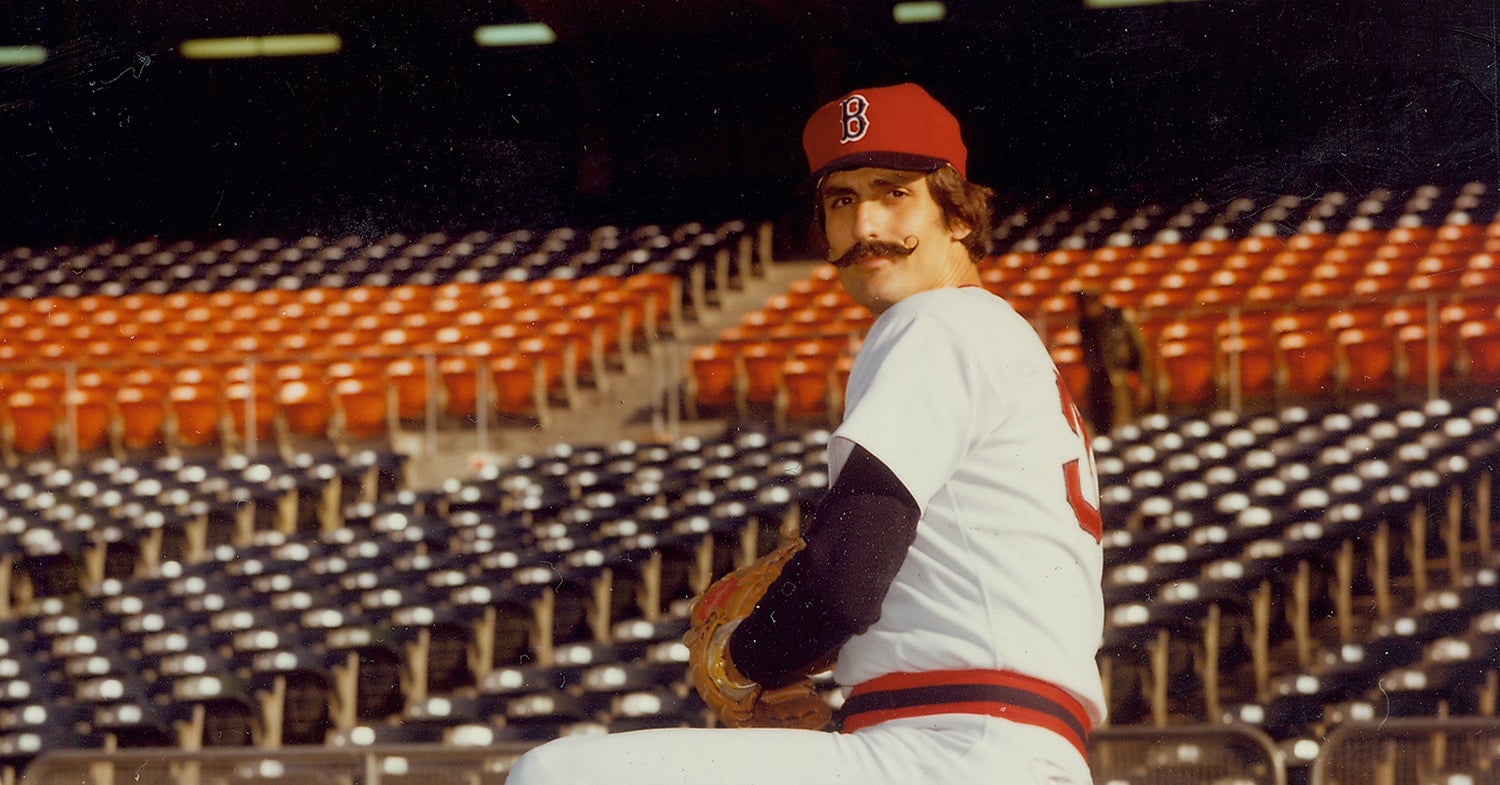

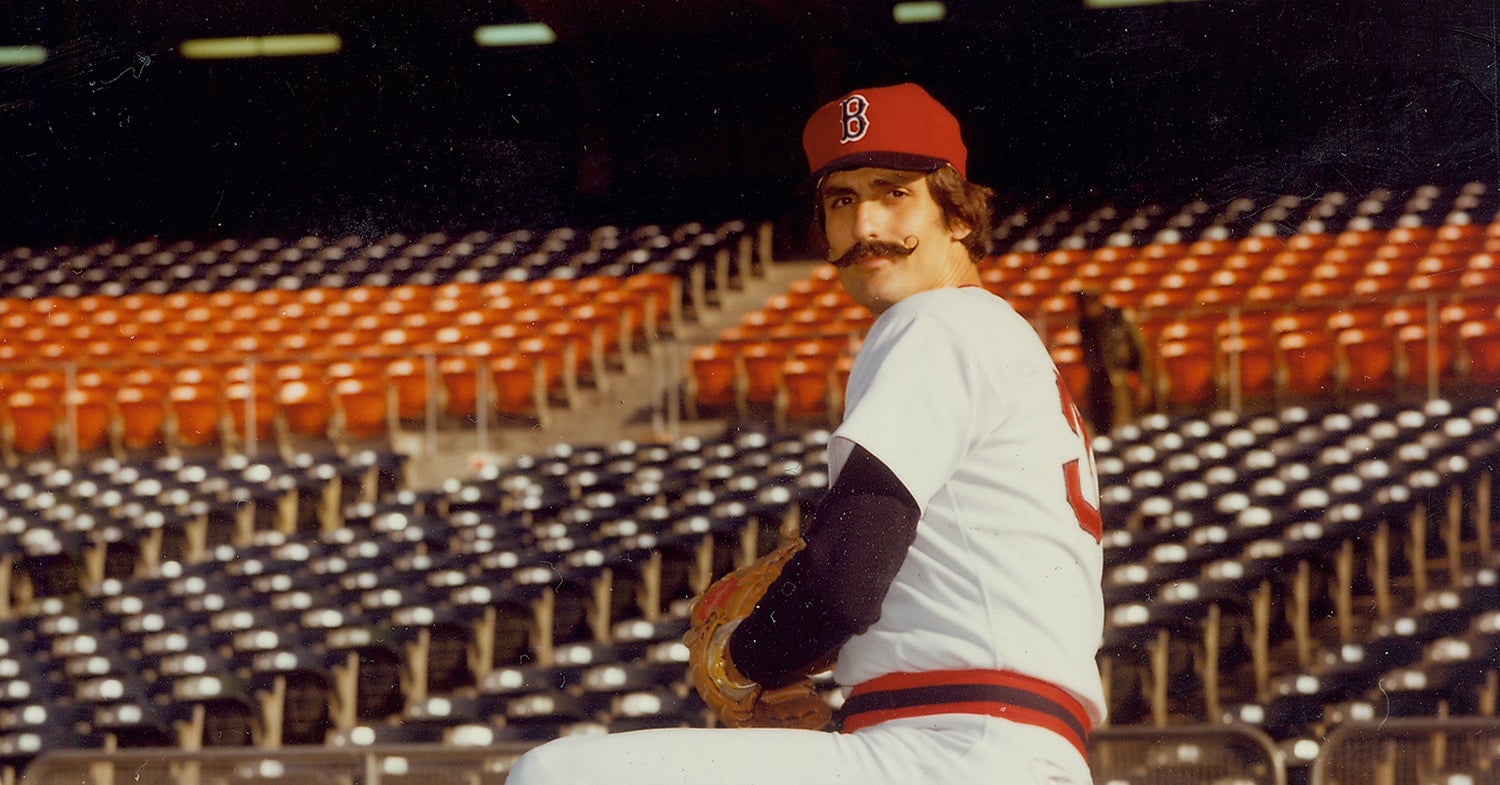

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

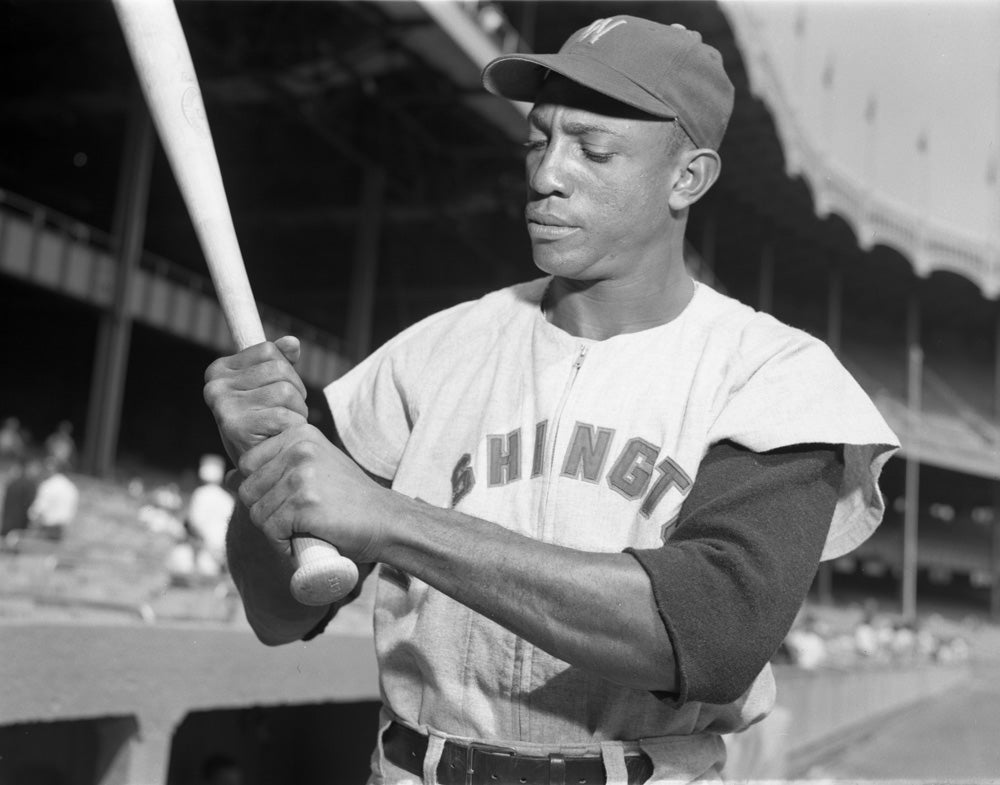

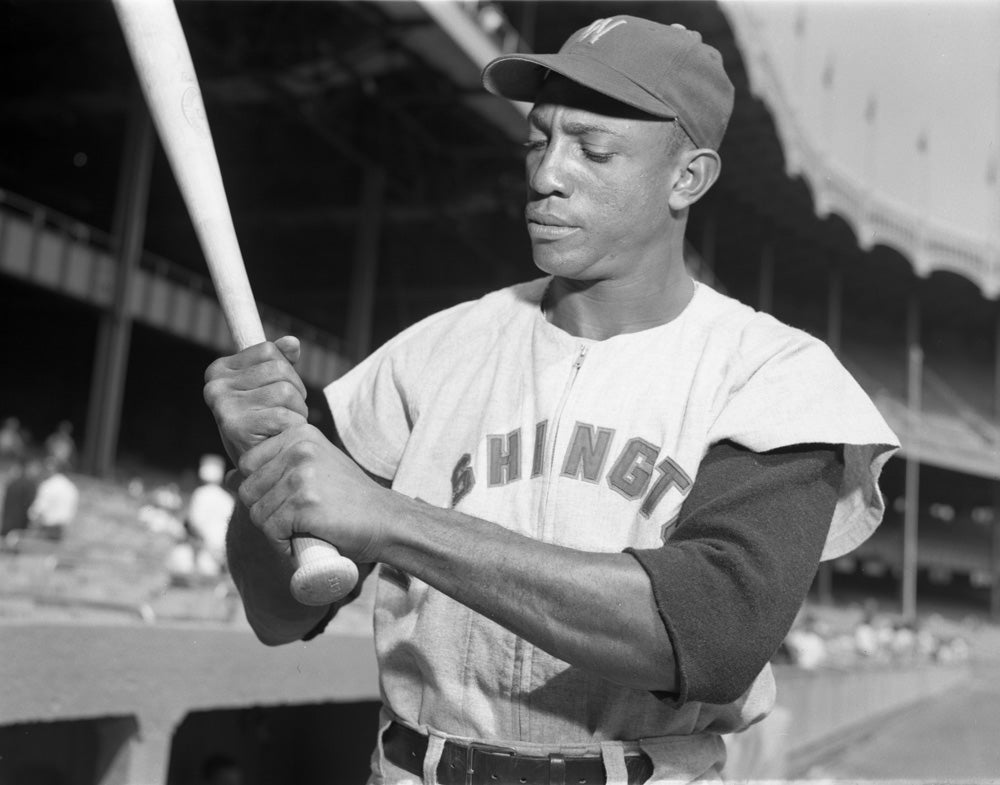

#GoingDeep: Carlos Paula, the man who integrated the Washington Senators

Rollie Fingers’ three days with the Red Sox

#GoingDeep: Carlos Paula, the man who integrated the Washington Senators

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Zisk’s Star Trident Comeback

Gary Herrmann - A King in Queen City

Just the Ticket for Cobb

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

The Holy Ball: Sparky and the Pope

From the Field to the Front Office

Red Sox trade Cy Young to Cleveland

1950 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr01d

01.01.2023

53 Hall of Famers Scheduled to Return to Cooperstown for July 24-27 Hall of Fame Weekend

01.01.2023