- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I’ve always liked Ken Phelps.

First, he was a player who persevered, despite being forced to spend too much time in the minor leagues when he should have been playing first base or serving as a DH for a major league team. Never giving up, he finally received his first significant chance at major league playing time with the Seattle Mariners at the age of 28. Second, Phelps would become immortalized on one of my favorite television shows, Seinfeld. (Much more on that later.) And third, Phelps just looked like a good, old-fashioned ballplayer, straight out of central casting for a movie like The Natural or even Bull Durham.

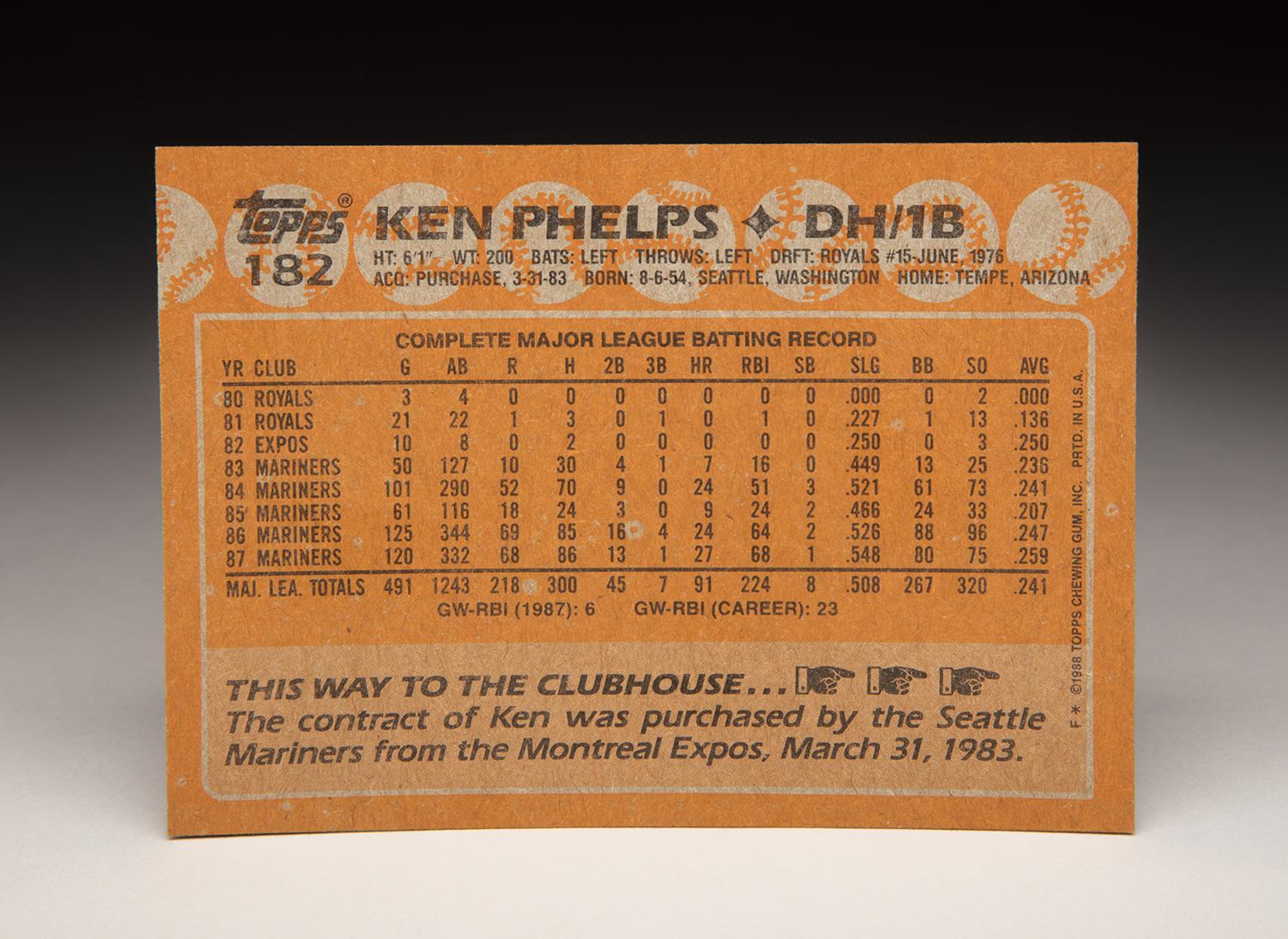

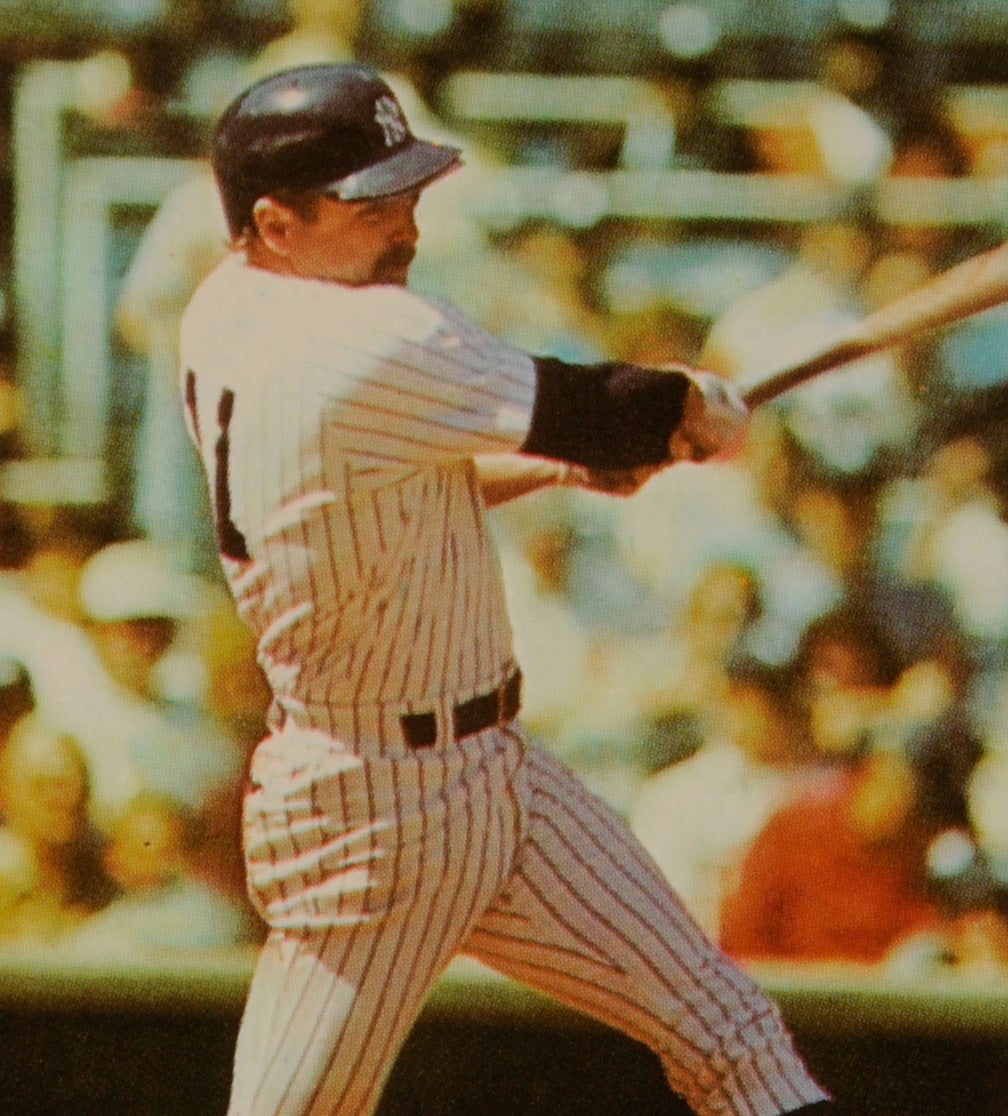

Let’s take a look at his card from 1988, a set with a simple design but plenty of action photography. This action shot shows Phelps at the plate, as he is getting ready to slide his left hand toward the handle of the bat. Phelps makes a good old-fashioned impression by wearing his stirrups and his pants properly, the way that they were meant to be worn, so that we can see the light blue stocking colors of the Seattle Mariners. On top of that, Phelps has the kind of bushy mustache and brawny physique (including a pair of Popeye forearms) that made him look like one of the rough-and-tumble players of the 19th century.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

If Phelps had shown up in John McGraw’s office looking like this, the Hall of Fame manager might have signed him on the spot – based on his rugged appearance alone.

As a developing baseball fan in the 1980s, I used to read Bill James’ annual Baseball Abstract, which were written with color and insight. “Digger” Phelps was a favorite of James, a player who should have been brought to the major leaguers sooner, but didn’t seem to appeal to the scouts. Lacking the lean, tapered look of some of the better athletes of the 1980s, Phelps didn’t run well and wasn’t particularly adept at playing first base. He also struck out too often, which would not have mattered much in today’s game, but was still considered a major shortcoming in the 1970s and 80s.

Talent evaluators seemed to minimize the two things that Phelps did very well: He hit lots of home runs and drew tons of walks. With a keen batting eye, Phelps rarely swung at pitches outside of the strike zone. When he wasn’t hitting a moonshot toward the gaps, he was taking a leisurely stroll to first base, making the walk an art form and himself into an unheralded on-base machine.

After being selected by the Kansas City Royals in the 15th round of the 1976 draft, Phelps worked his way gradually through the farm system. He finally earned his first taste of Kansas City in 1980, picking up a grand total of four at-bats. The following year, he received another cup of coffee, receiving only slightly more playing time: 22 at-bats in 21 games.

As a first baseman-DH, Phelps found himself blocked in Kansas City, where the Royals already had the lefty swinging Willie Mays Aikens at first base and veteran Hal McRae at DH. There was simply nowhere for Phelps to go within the organization. So in January of 1982, the inevitable took place: a trade. The Royals sent Phelps to the Montreal Expos in a one-for-one deal for veteran reliever Grant Jackson.

Unfortunately, the Expos already had a terrific first baseman in Al Oliver, who was about to embark on a season in which he hit .331 with 22 home runs. To make matters worse, the Expos, as a National League team, had no DH. So Phelps spent most of another wasted season at Triple-A, where he blasted 46 home runs. In September, he finally received a call-up to Montreal, where he played in a scant 10 games and came to the plate only nine times. Phelps was fast forging a career as the “Dead End Kid.”

Phelps repeatedly asked the Expos to trade him to a team that had more of a need for a first baseman or a DH. Thankfully, the Expos filled that request in the spring of 1983. Toward the end of Spring Training, the Expos mercifully sold Phelps to the Mariners, who were not as well stocked at first base as the Expos and who had the luxury of using the DH.

In his first year with Seattle, Phelps appeared in 50 games, which didn’t make him a regular but represented a vast improvement over his earlier situations in Kansas City or Montreal. Then came the breakthrough of 1984, the kind of season that the Phelps followers believed he was capable of delivering. Totaling 290 at-bats as a DH and first baseman, mostly against right-handed pitching, Digger belted 24 home runs and slugged .578. Prorated over a full season, Phelps would have hit roughly 45 to 50 home runs.

That performance launched an extremely productive stretch of seasons for Phelps in Seattle. From 1984 to 1988, Phelps slugged at least .521 or better each year, with the exception of a lost 1985. He didn’t strike out as often as most power hitters (never fanning as much as 100 times in any season), and over a three-year span, he drew more walks than strikeouts. He especially enjoyed playing for Hall of Fame manager Dick Williams, who took over the helm of the Mariners in the middle of 1986.

With the Mariners headed toward a last place finish in 1988 and looking to make their team younger and more athletic, they put Phelps on the block in the middle of the season. For much of the first half of the season, trade rumors swirled around Phelps, with many of the rumors centering on the New York Yankees. In fact, the Yankees had talked about acquiring Phelps for three years, starting in 1985. Owner George Steinbrenner became obsessed with acquiring Phelps, whose hitting approach also drew raves from scouts. With his left-handed power, the Yankees thought that Phelps could become a monster at Yankee Stadium.

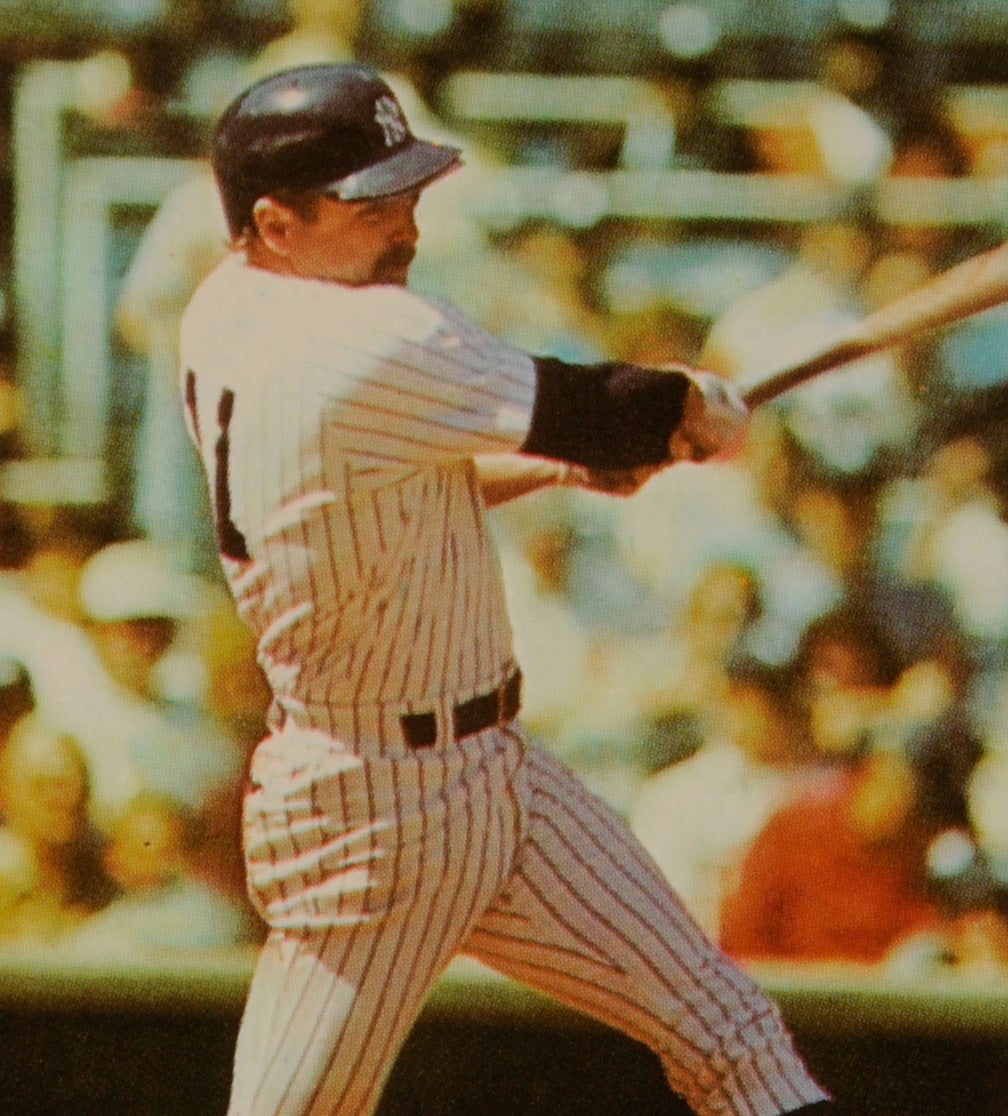

After weeks of rumors, a trade finally became reality. On July 21, the Yankees completed a major deal with the Mariners, sending outfield prospect Jay Buhner and two lesser prospects to Seattle for Phelps. As a result, Phelps’ 1988 Topps card quickly became outdated, but Topps wouldn’t show him in his new Yankee colors until the new 1989 set hit stores in February.

Having read so much about Phelps in the Baseball Abstract, I was thrilled about the trade for the Yankees. I also had some doubts about Buhner, the primary player the Yankees sent to the Mariners. While Buhner was a top prospect, he also had several holes in his swing, which tended to run long and carried too much of an uppercut. Buhner also struck out at an alarming rate, and as a right-handed hitter, appeared to be a bad fit for the Death Valley dimensions of Yankee Stadium.

On paper, the deal looked terrific to me, but my hopes at becoming a great talent evaluator would soon be dashed. The trade did not work out as planned. The Yankees tried to use Phelps as a DH against right-handers, allowing them to alternate days off for talented but aging right-handed hitters like Jack Clark and Dave Winfield, but Yankees manager Lou Piniella could never seem to figure out how to get Phelps into the lineup more often. The irregular playing time left Phelps frustrated. “I just sit here and scratch my head and wonder what they have in store for me,” Phelps told the New York Post in August. “I wonder how I fit in.”

From late July through the end of the season, Phelps played in 45 games and accumulated only 127 plate appearances. Phelps hit well in those games, pounding out 10 home runs to the tune of a .551 slugging percentage, but Yankee fans often booed him because they considered him an unwanted outsider. Frankly, Phelps should have played every day, but the presence of Clark, Winfield and several other premier talents made that difficult. As it was, the Yankees finished a disappointing fifth in the American League East pennant race.

The situation only worsened in 1989. Phelps went from being a productive hitter to a slumping slugger. Now 34, he suddenly looked old, unable to catch up to high-octane fastballs. He also struggled with the dimensions of the old Yankee Stadium. With his power gravitating toward left-center and right-center field, Phelps lacked the kind of pull-hitting swing that a lefty needed to take full advantage of the Stadium’s short field porch.

Phelps also became involved with a mild controversy in 1989. During the spring, it became known that Phelps, who had been a vocal clubhouse leader with the Mariners, had complained to the Yankee coaches about the amount of drinking that he saw on the team’s flights in 1988. Having played for the Mariners, who did not allow alcohol on any of their team flights, Phelps felt the presence of so much alcohol on the Yankee flights created a potentially ugly situation. In response to the complaints, Lou Piniella banned all use of hard liquor on the team plane. Some of the veteran Yankees resented

Phelps for indirectly causing the change in team policy.

More importantly, Phelps lost his job as the Yankees’ principal DH by midseason. With Phelps struggling and the Yankees well out of contention, the team made a move in August, sending Phelps to the Oakland A’s for a minor league left-hander named Scott Holcomb. Just like that, the Ken Phelps Era had come to an end in the Bronx.

In the meantime, Buhner developed into a near-star in Seattle, becoming a productive power hitter with a cannon arm that played well in the old Kingdome. He would remain an effective right fielder through the 2000 season, before injuries finally caught up with him in 2001, forcing his retirement. Of all the ill-conceived trades that the Yankees made in the 1980s, this turned out to be one of the worst.

I feel bad that Yankee fans never really saw the real Ken Phelps. If they had witnessed the player who had mashed right-handed pitching during the mid-1980s, they would have been left with a far different impression. That version of Phelps could hit and get on base, as one of the most quietly productive players of the decade.

In moving on to Oakland, Phelps became a bench player and part-time DH. He struggled with the A’s, with perhaps his only highlight in 1990 coming in a game against his former team, the Mariners. Phelps hit a pinch-hit home run in the ninth inning to break up Brian Holman’s bid at a perfect game on April 20. That turned out to be the final home run of Phelps’ career.

Shortly thereafter, the A’s sold Phelps to the Cleveland Indians. He didn’t hit much for the Indians, soon drawing his release. In 1991, Phelps tried to make a comeback with the Giants’ organization, but played only seven games for Triple-A Phoenix before the Firebirds released him. Just like that, he was done, another cruel example of how quickly a baseball career can come to an end. Other than a one-year stint as a broadcaster, Phelps left the game completely, becoming almost virtually forgotten by fans and followers of the game.

But the folks at Seinfeld did not forget. On Jan. 25, 1996, the episode titled “The Caddy” aired on NBC for the first time. George Steinbrenner, voiced by Larry David, shows up at the home of George Costanza’s parents to inform them that their son has died. In response to the news, the unhinged character of Frank Costanza (played so brilliantly by comedic icon Jerry Stiller), frenetically exclaims, “What the hell did you trade Jay Buhner for? He had over 30 home runs and 100 RBIs last year. He’s got a rocket for an arm. You don’t know what you’re doing!”

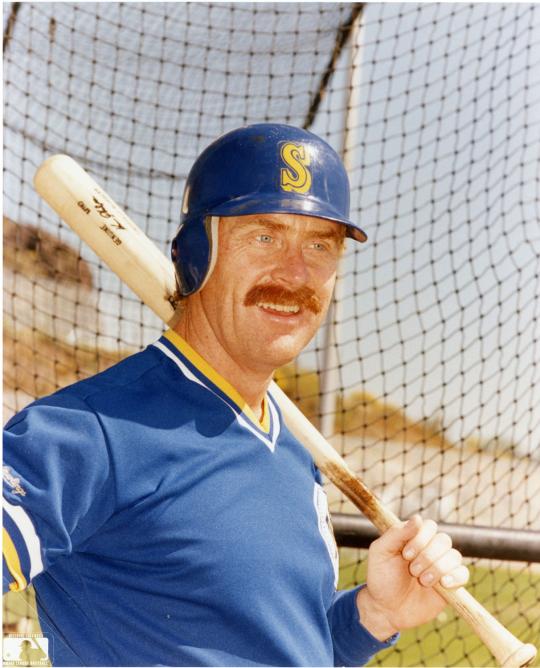

Ken Phelps played for the Seattle Mariners from 1983-1988. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

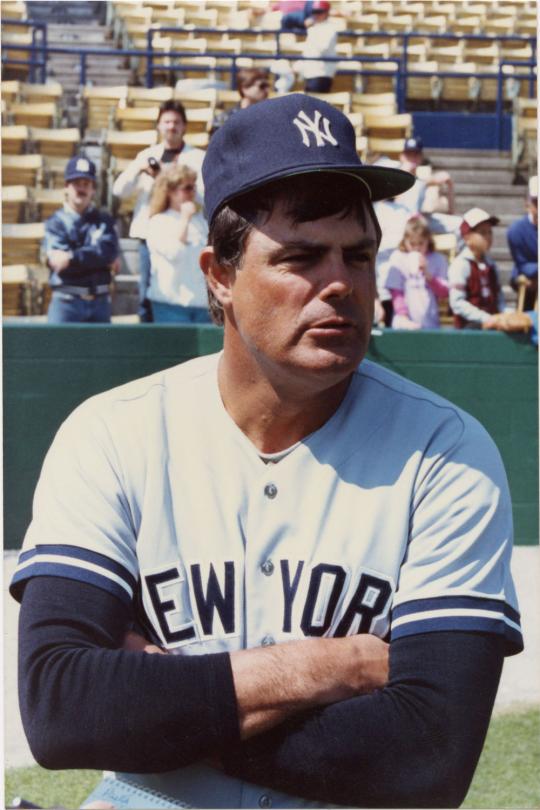

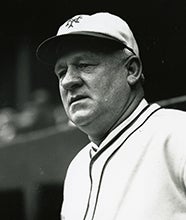

The New York Yankees tried to use Ken Phelps as a designated hitter against right-handers, but manager Lou Piniella (pictured above) had a difficult time incorporating Phelps into the lineup. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

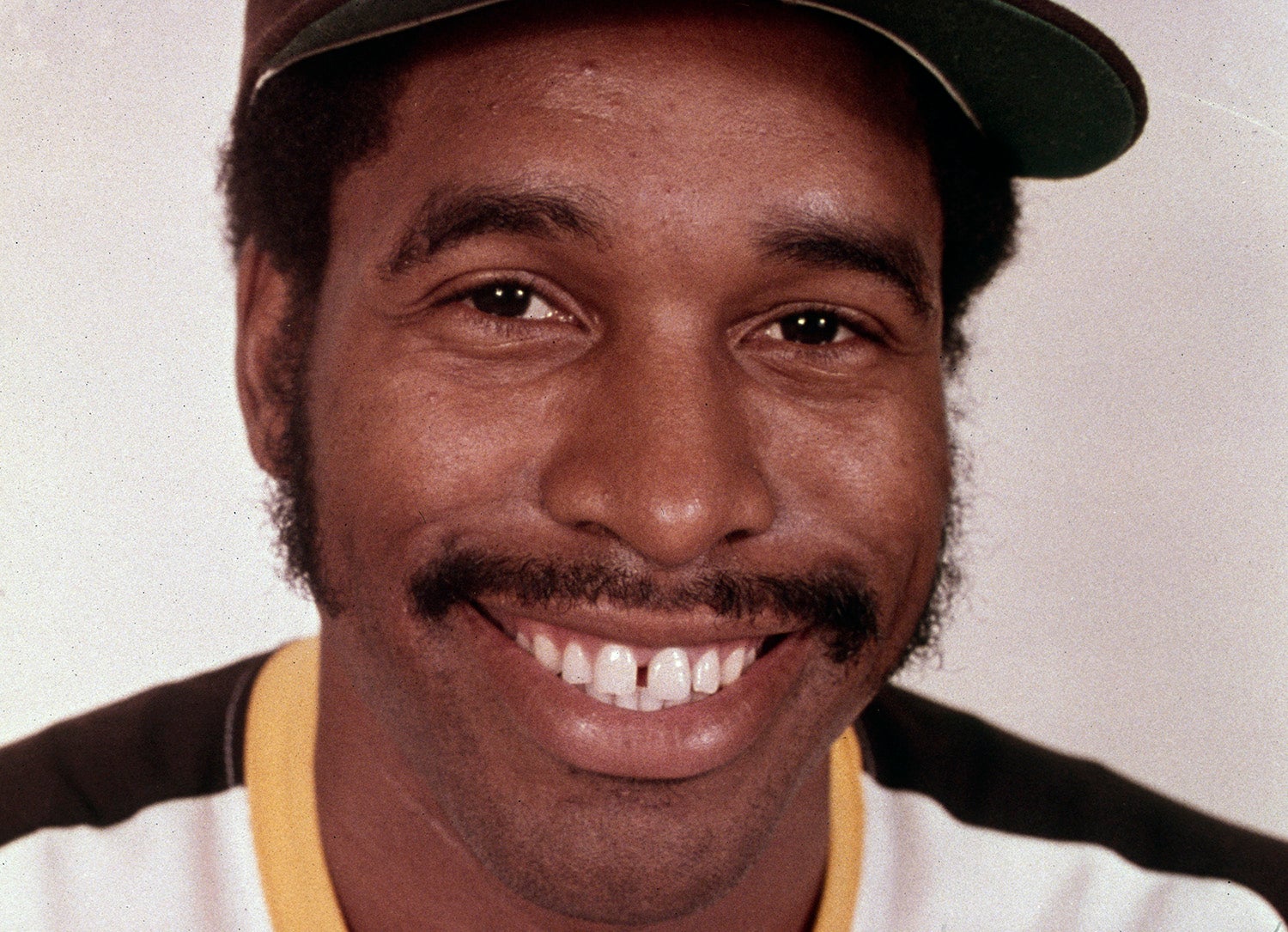

When he was on the Mariners, Ken Phelps played for Hall of Fame manager Dick Williams, who took the helm in 1986. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

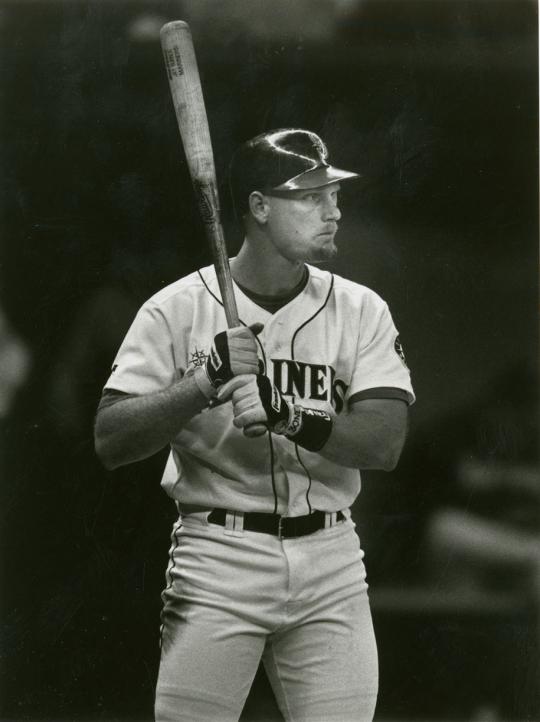

On July 21, 1988, the New York Yankees completed a major deal with the Seattle Mariners, sending outfield prospect Jay Buhner (pictured above) and two other prospects to Seattle for Ken Phelps. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In rapid-fire delivery, Steinbrenner responds, “Well, Buhner was a good prospect, no question about it. But my baseball people loved Ken Phelps’ bat. They kept saying Ken Phelps, Ken Phelps!”

For baseball fans, both Mariners and Yankees alike, the exchange between The Boss and Frank hit home. To his credit, the easygoing Phelps has remained a good sport about the Seinfeld episode. In fact, in 2015 he and Buhner reunited at the Mariners’ Spring Training camp in Peoria, Ariz., where they both enjoyed a robust laugh over the Seinfeld parody.

“It’s nice to be remembered for something,” a smiling Phelps told reporters that day.

This fan of Phelps remembers him for a lot more, including his perseverance and professionalism. But I must admit that the Seinfeld reference completes the picture beautifully. As long as that episode continues to air in reruns, Ken Phelps has no chance of ever being forgotten again.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

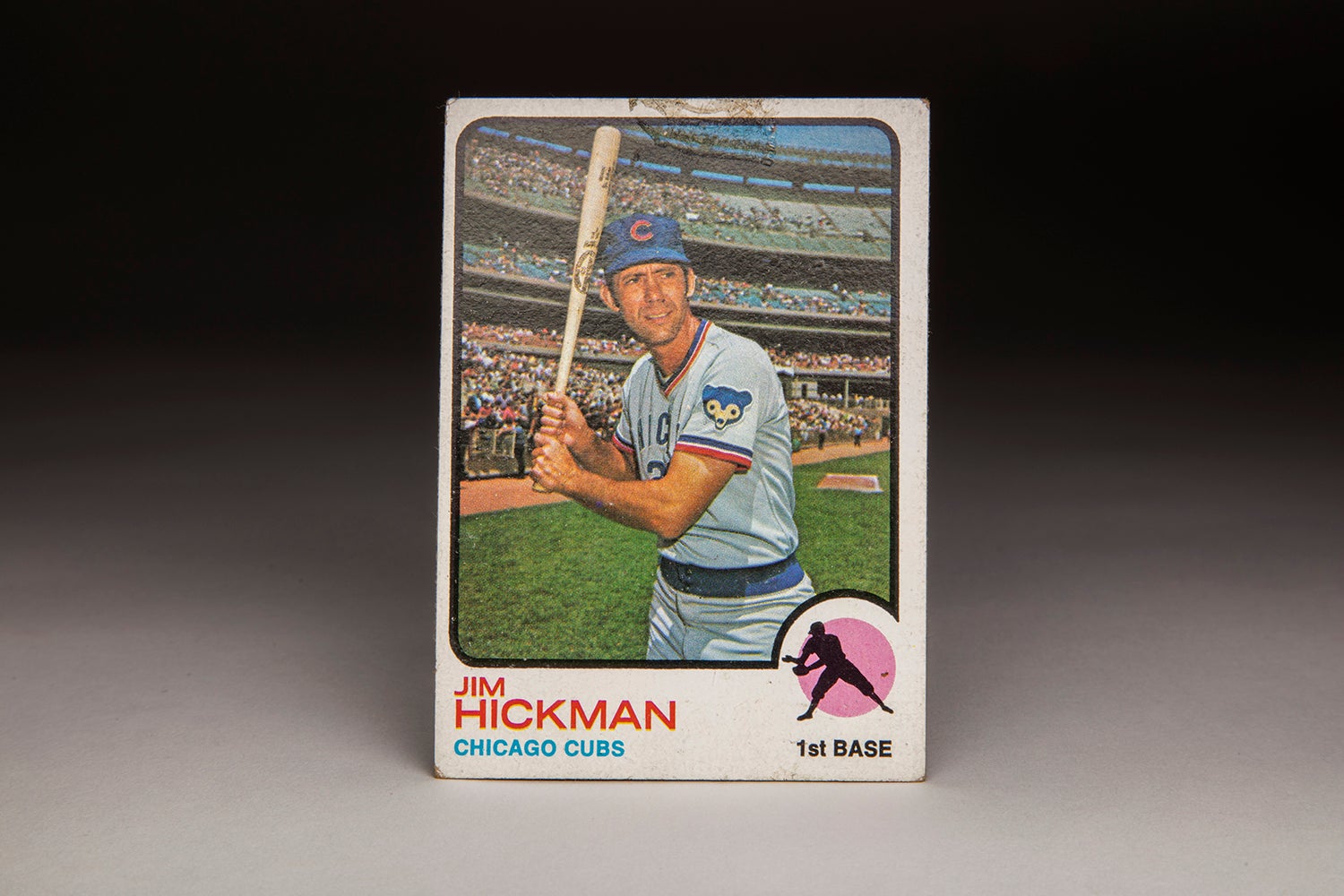

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

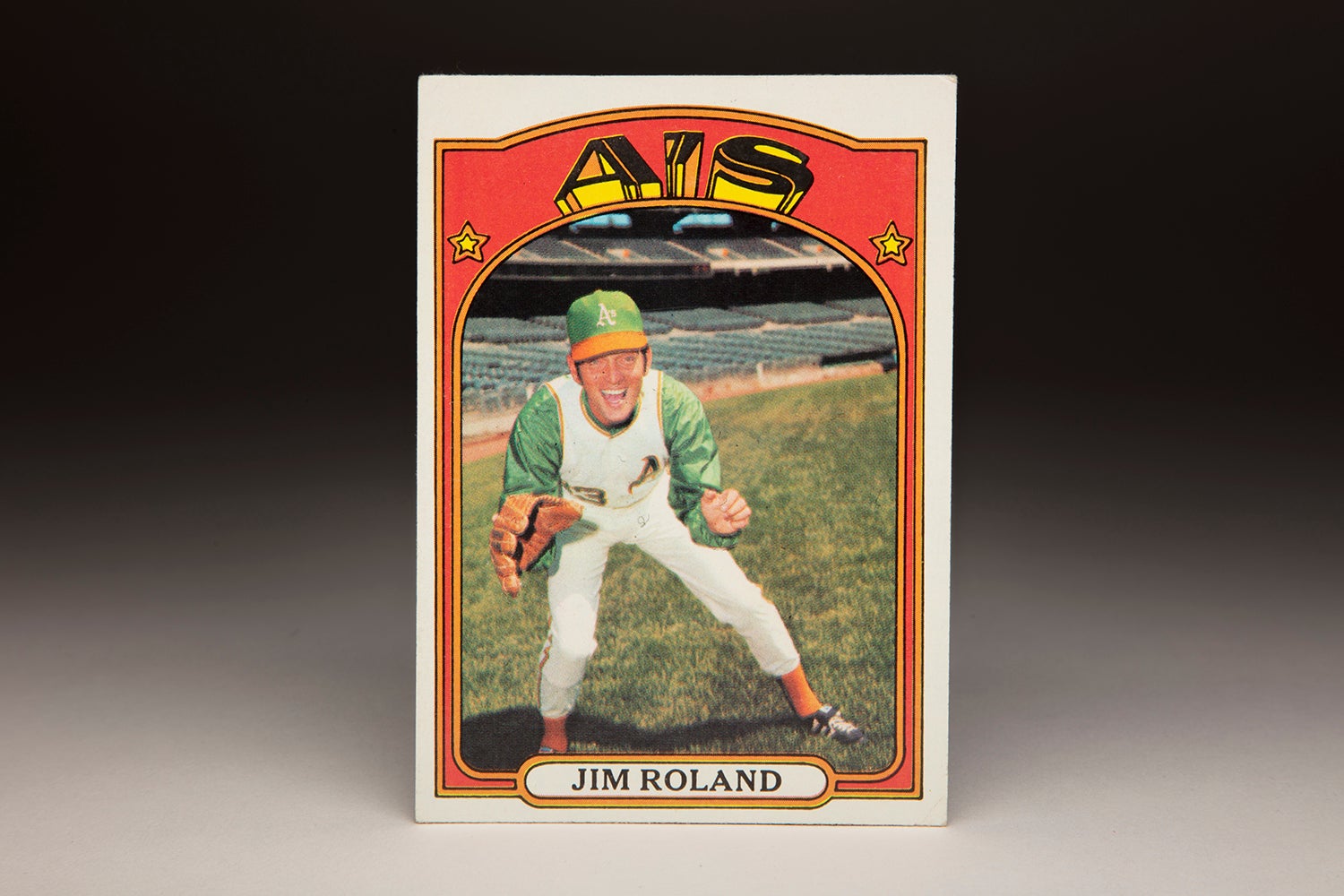

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jim Roland

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jim Roland

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#PopUps: Meb's First Pitch

A ticket fix

Griffey, Piazza honored by Hall election

1960 Hall of Fame Game

Relive Inductees’ Hall of Fame Weekend Journey at Legends of the Game Roundtable Event

Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson born

Lou Gehrig hits four consecutive home runs

Astrodome barely contains Mike Schmidt’s blast

Bobby Doerr Becomes Oldest Hall of Famer

01.01.2023