- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

For many years, the New York Yankees emphasized defensive play with their shortstops. First, there was Gene “Stick” Michael, followed by Fred “Chicken” Stanley, and then Bucky Dent.

It’s hard to believe now, but prior to Dent’s historic home run against the Boston Red Sox in the 1978 American League East playoff, he wasn’t among the most well-known Yankees.

Although Dent was reliable defensively, he had ordinary range and rarely made spectacular plays. He was also a relatively light hitter. But he fit into the context of what the Yankees needed and wanted: A fine fielding shortstop who could make the routine plays.

For most of the latter half of the 1970s, a contingent of Yankee fans wanted the team to replace Dent with one man: Toby Harrah. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner shared that same dream, because every summer, newspapers in New York City and Westchester County reported rumors that the team was working on a deal for Harrah. At the time, Harrah was the starting shortstop for the Texas Rangers.

Some people regarded Toby Harrah as a subpar defensive shortstop, but some Yankees fans grew excited about the other side of Harrah’s game: His ability to hit. He reached the 20-home run mark three times with the Rangers, usually hit .260 or better, annually achieved double figures in stolen bases, and drew a ton of walks.

Harrah had come a long way in just a few seasons with the Rangers. When he had made his major league debut, the Rangers were still the Washington Senators, and Harrah was a scrawny 160-pound, light-hitting middle infielder. But by the middle of the 1970s, he had evolved into a strong 180-pounder who could more than hold his own against American League pitching.

Harrah represented a rare breed in 1970s baseball: An American League shortstop who could hit and hit with power. Keep in mind that Hall of Famer Robin Yount had not yet entered his prime, Alan Trammell wouldn’t arrive in Detroit until 1978 (and even then he was only 20), and Hall of Famer Cal Ripken, Jr.s’ debut remained several years away. Most AL shortstops fell into the one-dimensional category of all-field and little-hit, including the likes of Mark “The Blade” Belanger, Dave Chalk, Frank Duffy, and Tom Veryzer. Compared to those light hitters, Harrah looked like an Adonis in the batter’s box.

Even though the Rangers moved Harrah from shortstop to third base in 1977, largely because of knocks against his range and reliability, Harrah seemed to have enough athletic ability to make the switch back. As long as Harrah could play shortstop reasonably well – you know, better than Bobby Murcer once did – Yankee fans were going to be satisfied. There existed a hope that Steinbrenner and the Yankees’ general manager at the time (Gabe Paul, followed by Al Rosen) would do whatever they could to get that deal done.

Harrah was also a likeable player. Ever since he had joined the Senators, he had forged a reputation as one of the game’s wholesome characters. He answered questions from reporters by addressing them as “sir.” He used words like “golly” and “gee,” in stark contrast to the usual profanity that flowed in major league clubhouses.

Harrah also brought a toughness to the playing field. He hardly ever took days off. “I was the type of player who would do anything to beat you,” Harrah once told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Hit behind the runner, steal a base, break up a double play, play every day. I wanted to win in the worst way.”

Given all of these attributes, the plan to bring Harrah to New York sounded good. Considering the depth of the Yankees’ pitching staff, giving up a second-tier pitcher in addition to Dent seemed doable. There was just one problem. The Rangers had to agree to the deal, too. They wanted more than Dent and a secondary pitcher. They negotiated with the Yankees off and on, with Harrah’s name periodically being mentioned in rumors, but the two sides could not reach the appropriate compromise. After the 1978 season, the Rangers finally received an offer they couldn’t refuse. Only it didn’t come from the Yankees. Instead, the Rangers found a trading partner in the Cleveland Indians, who agreed to give up All-Star third baseman Buddy Bell in return for Harrah.

Harrah spent five mostly productive seasons with the Indians. By the early 1980s, Yankee fans had already forgotten about Harrah, who had entrenched himself as a durable and productive player in Cleveland. It was time to move on. The dream had ended.

In February of 1984, with the Yankees collecting infielders in a strangely obsessive way, the team announced a surprising trade. The deal sent reliever George Frazier and minor league speedster Otis Nixon to the Indians for Harrah. By then, Harrah was no longer a shortstop; he had long since been converted to third base. He was no longer an All-Star either, with his home run production falling off from 25 to nine in his final season with Cleveland. At 34, Harrah looked well past his prime.

Lots of folks didn’t understand the trade. The Yankees already had Graig Nettles and Roy Smalley available to play third. Nettles eventually vacated the premises, mostly because of the controversial contents of his tell-all book, Balls.

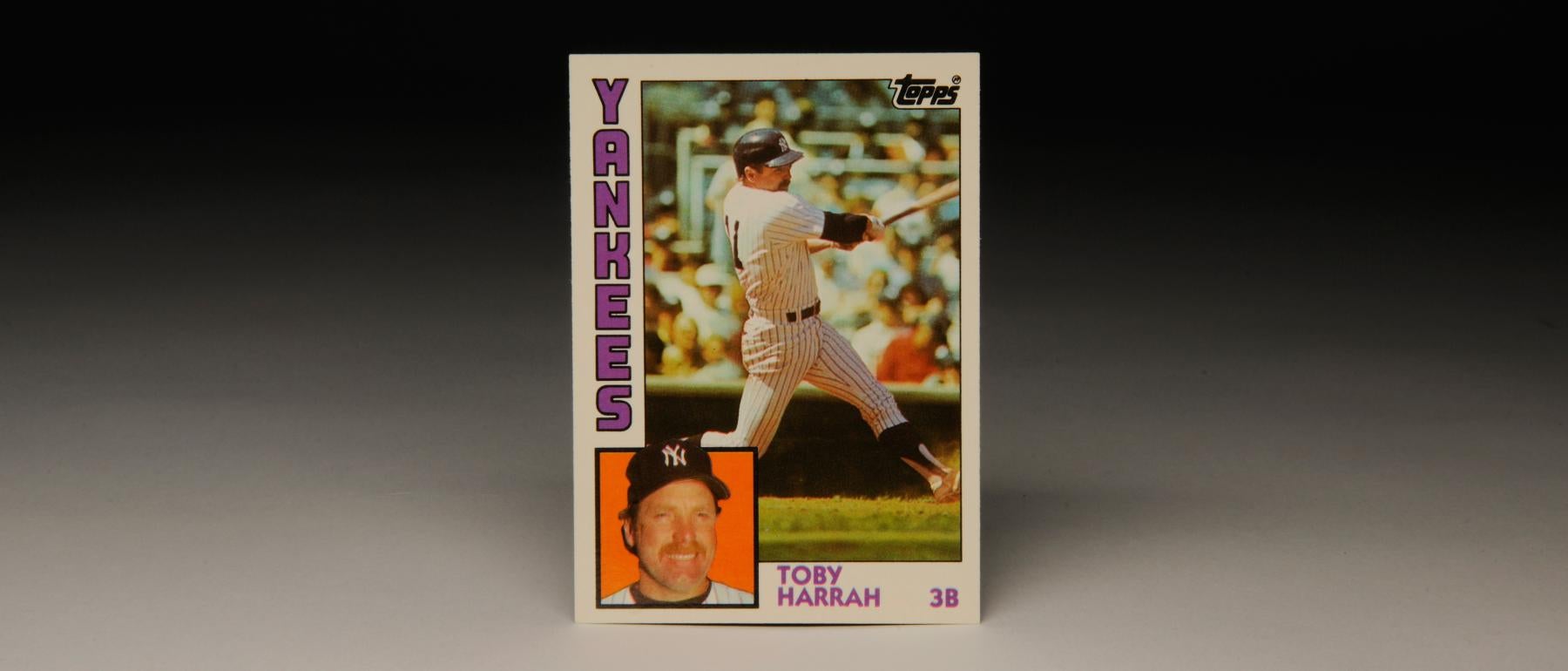

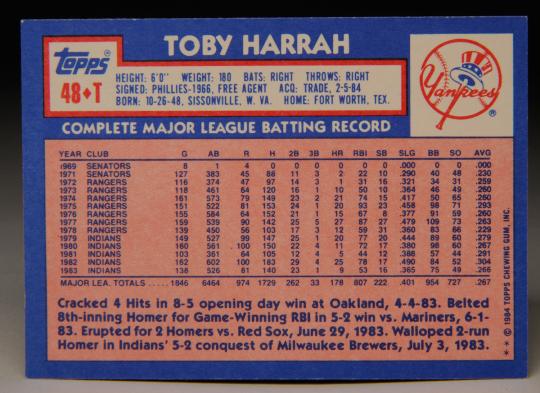

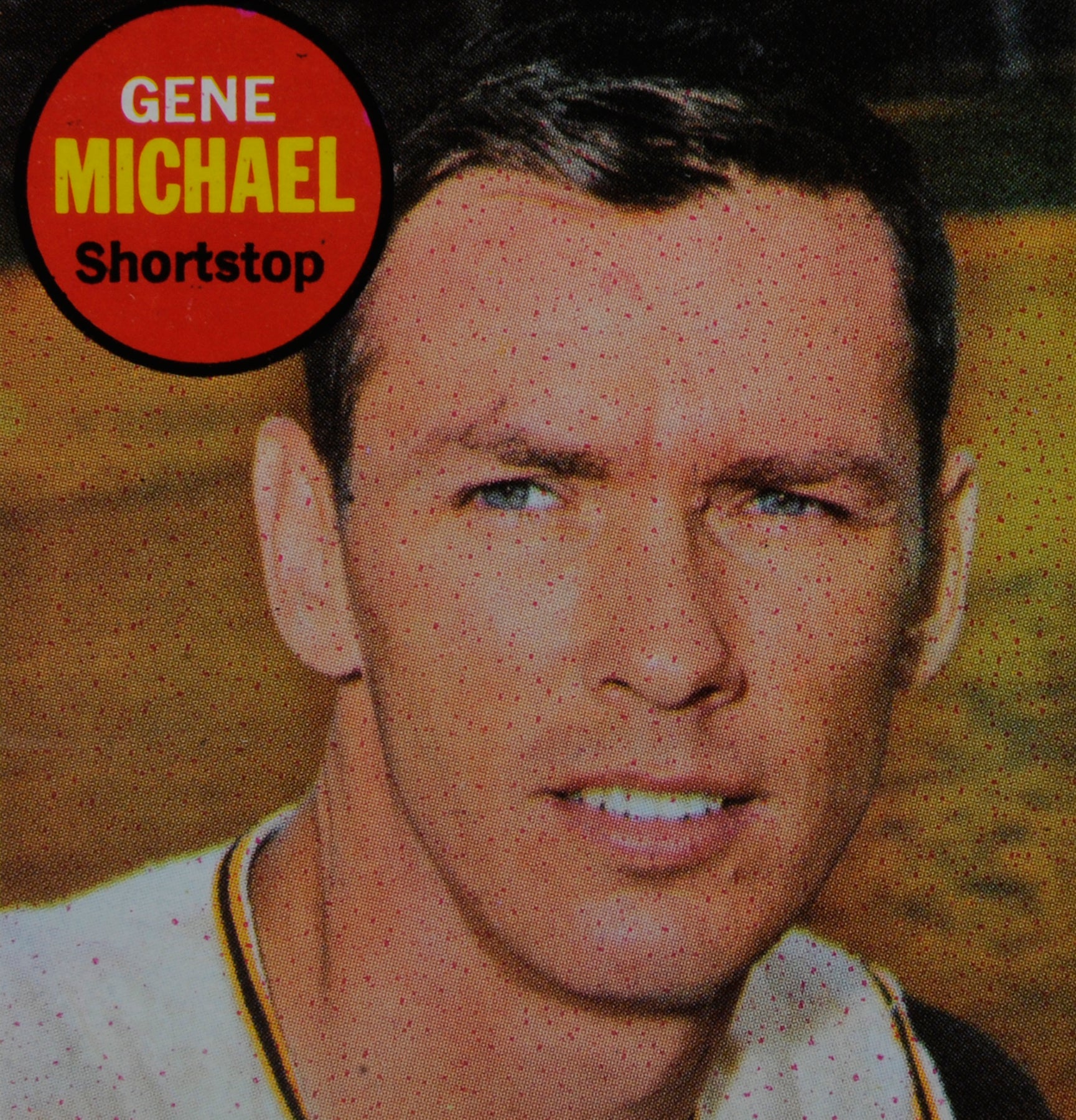

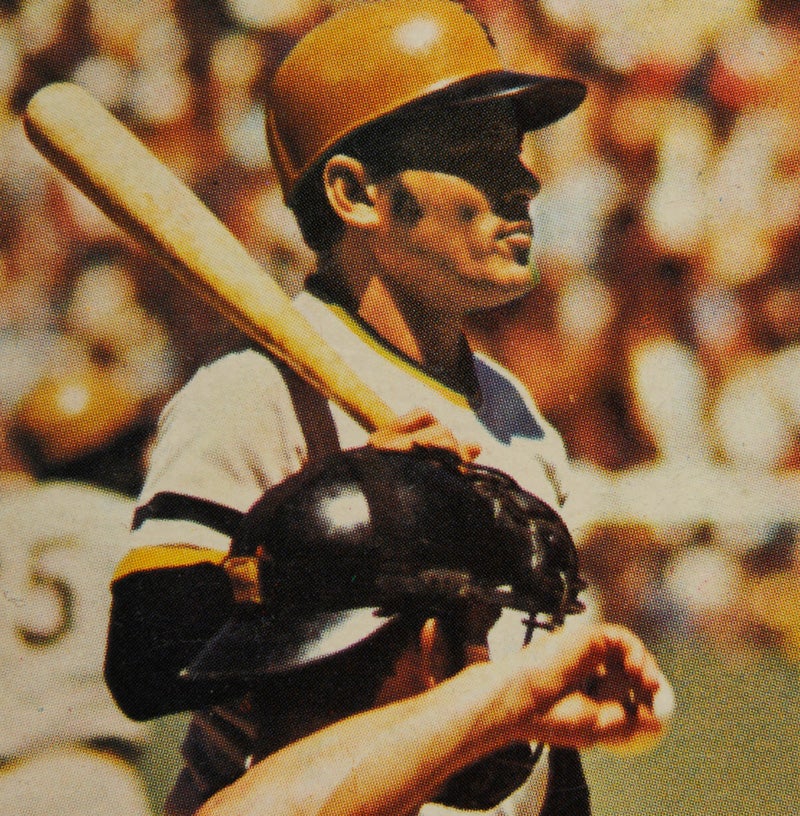

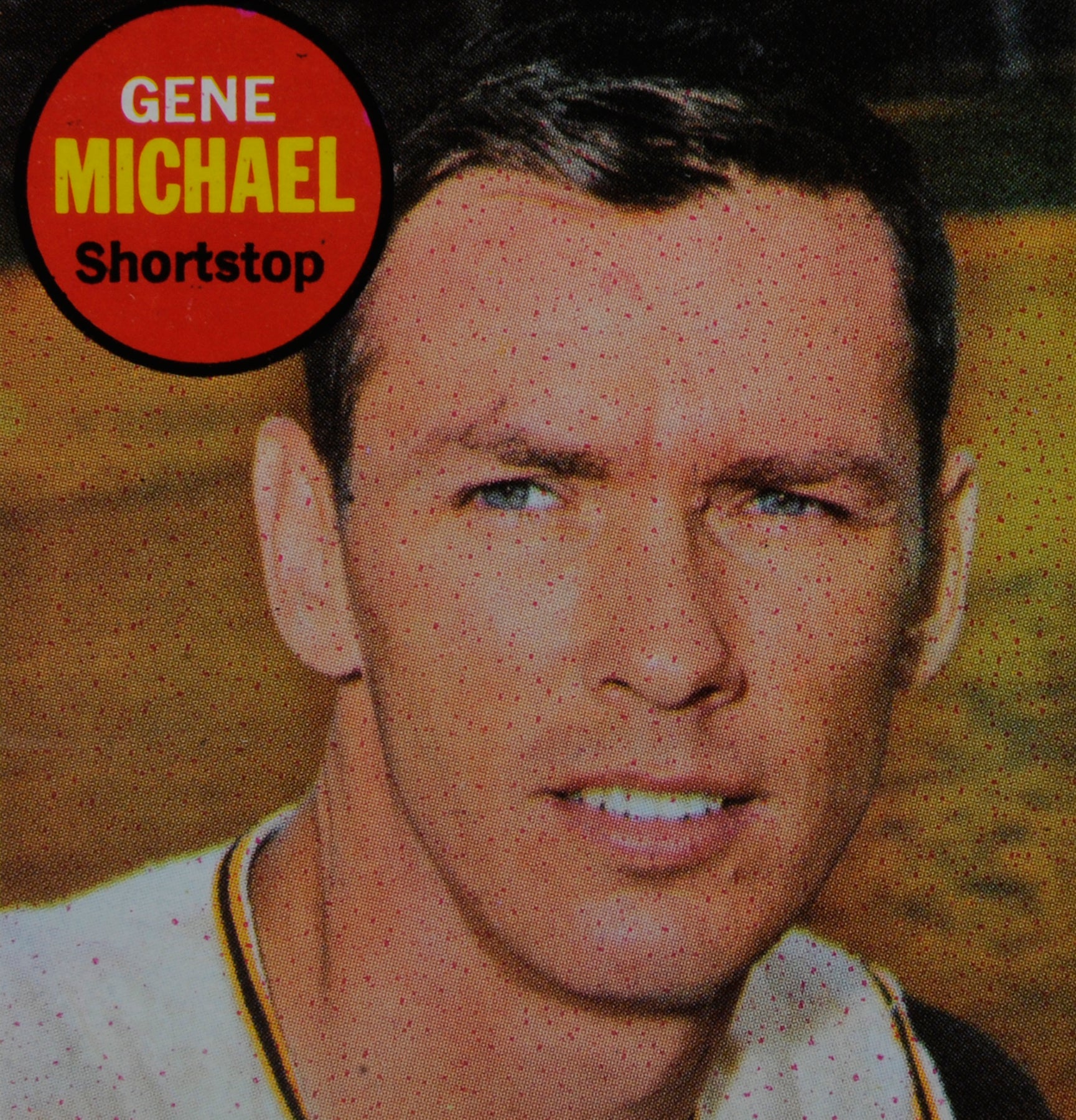

Still, it was exciting to hear that Harrah had finally become a Yankee. It was also thrilling to see his 1984 Topps Traded card. Earlier in the spring, Topps had released its regular issue card of the bearded Harrah, showing him playing third base for the Indians. By the middle of the summer, Topps had released its 132-card Traded set, which included Harrah with his newest team. Now, for the first time ever, a Topps card actually depicted Harrah playing for the Yankees.

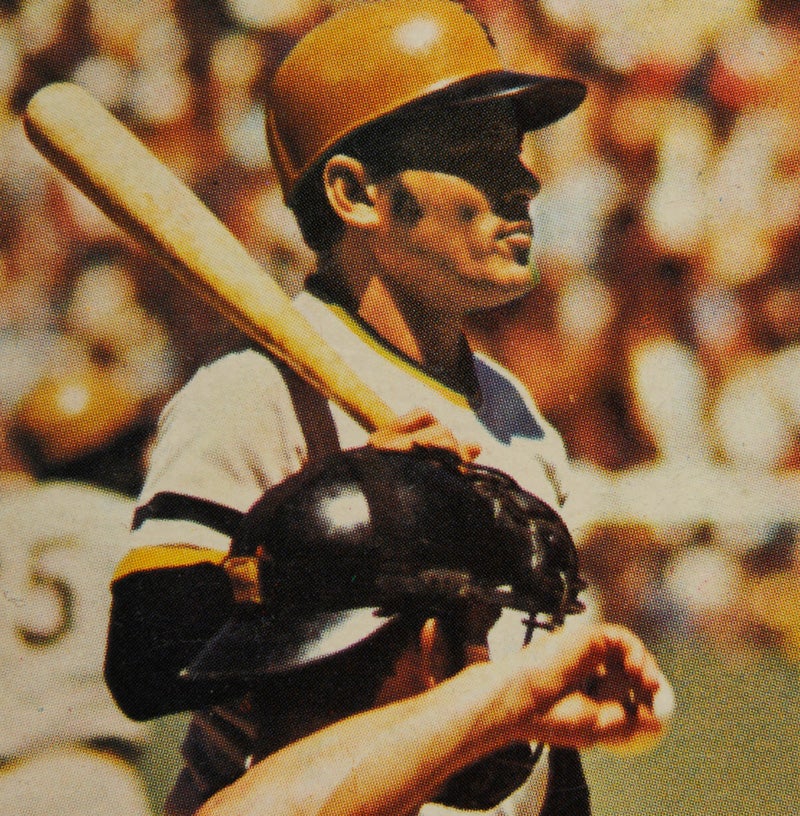

Of all the Harrah cards produced during his career, this is one of his best. It’s a clear action shot from a day game at Yankee Stadium, capturing Harrah just a moment after he has made contact with the pitch. His body is balanced, even while his front leg is fully extended toward the pitcher. His head is down and his hands maintain a firm grasp on the bat, which is pointed artfully toward left field. Although we cannot know for sure where the ball has been hit, all of the signs contained within Harrah’s body language indicate that he has made solid contact, the kind that produces a line drive or a long fly ball toward the outer reaches of Yankee Stadium.

Even the inset picture looks good. His beard his gone, but his trademark mustache remains in place, as does a Yankee cap covering his balding head. Without the beard, this looks like a younger Harrah in his prime. Sporting a wide smile, Harrah appears thrilled to be a member of the Yankees.

As good as this card is, Harrah’s career with the Yankees did not match it. He did not like playing in New York, nor did he play well. Harrah ended up splitting time with Smalley, hit all of one home run in pinstripes, slugged an inadequate .296, and batted only .217. Clearly not the player he once was, Harrah became trade bait after the season, as the Yankees dealt him to the Rangers for outfielder Billy Sample. Harrah would play better in Texas, well enough to become their starting second baseman, but that only made the situation more frustrating for Yankee fans.

In the meantime, the Yankees continued their search for a new shortstop, some of whom could hit, some of whom could field, and some who could do neither. Smalley (who had been a very good player with the Minnesota Twins) tried and failed, as did Andre Robertson, Bobby Meacham, Paul Zuvella, Wayne Tolleson, Rafael Santana, Alvaro Espinoza, Spike Owen, and even a fading Tony Fernandez.

The Yankees’ quagmire of shortstop mediocrity continued until 1995. That’s when Toby Harrah finally arrived. Not the actual Toby Harrah, but a newer, better version of Toby Harrah.

Like Harrah, he would receive criticism for his defensive struggles, but he would do wondrous things offensively. He would also spearhead the next Yankee dynasty, winning five world championships along the way.

Yes, Toby Harrah finally did arrive – in the form of a 21-year-old phenom named Derek Jeter.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

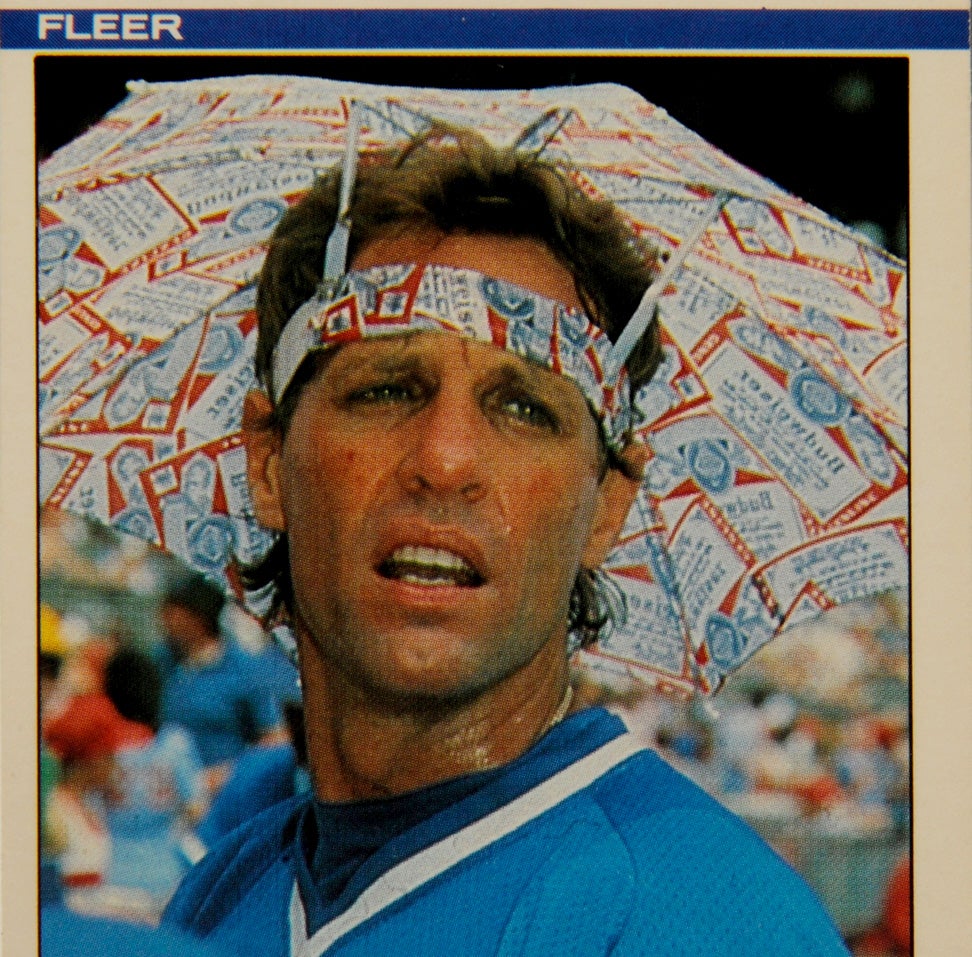

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

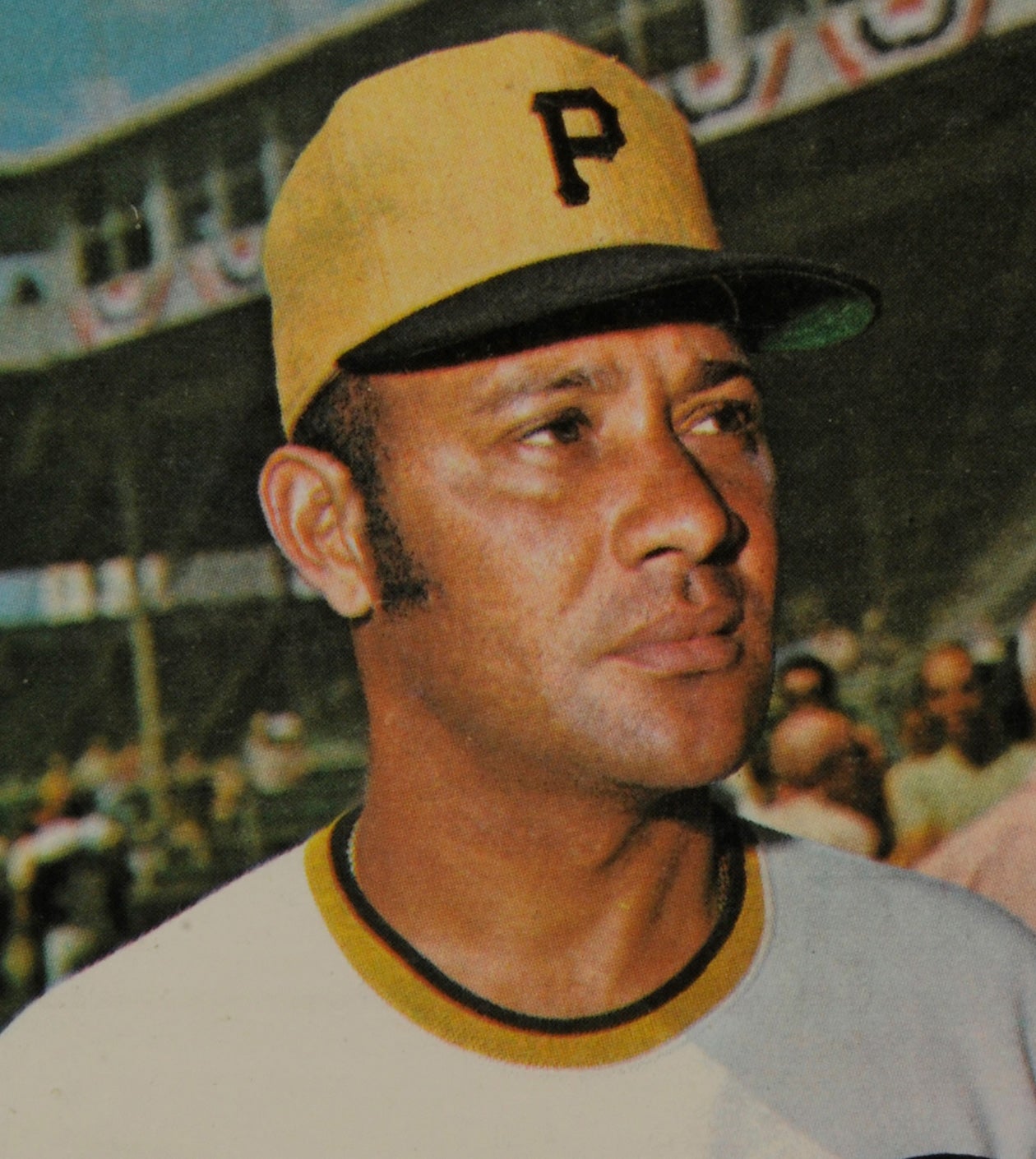

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Nolan Ryan eclipses Walter Johnson’s strikeout record

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr01a

The Dream of the '90s

Hoop Hall legend Dan Issel visits Cooperstown

Cardinals trade Steve Carlton to Phillies

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Chico Salmon

#GoingDeep: Ted Williams Heads Back to War

1997 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023