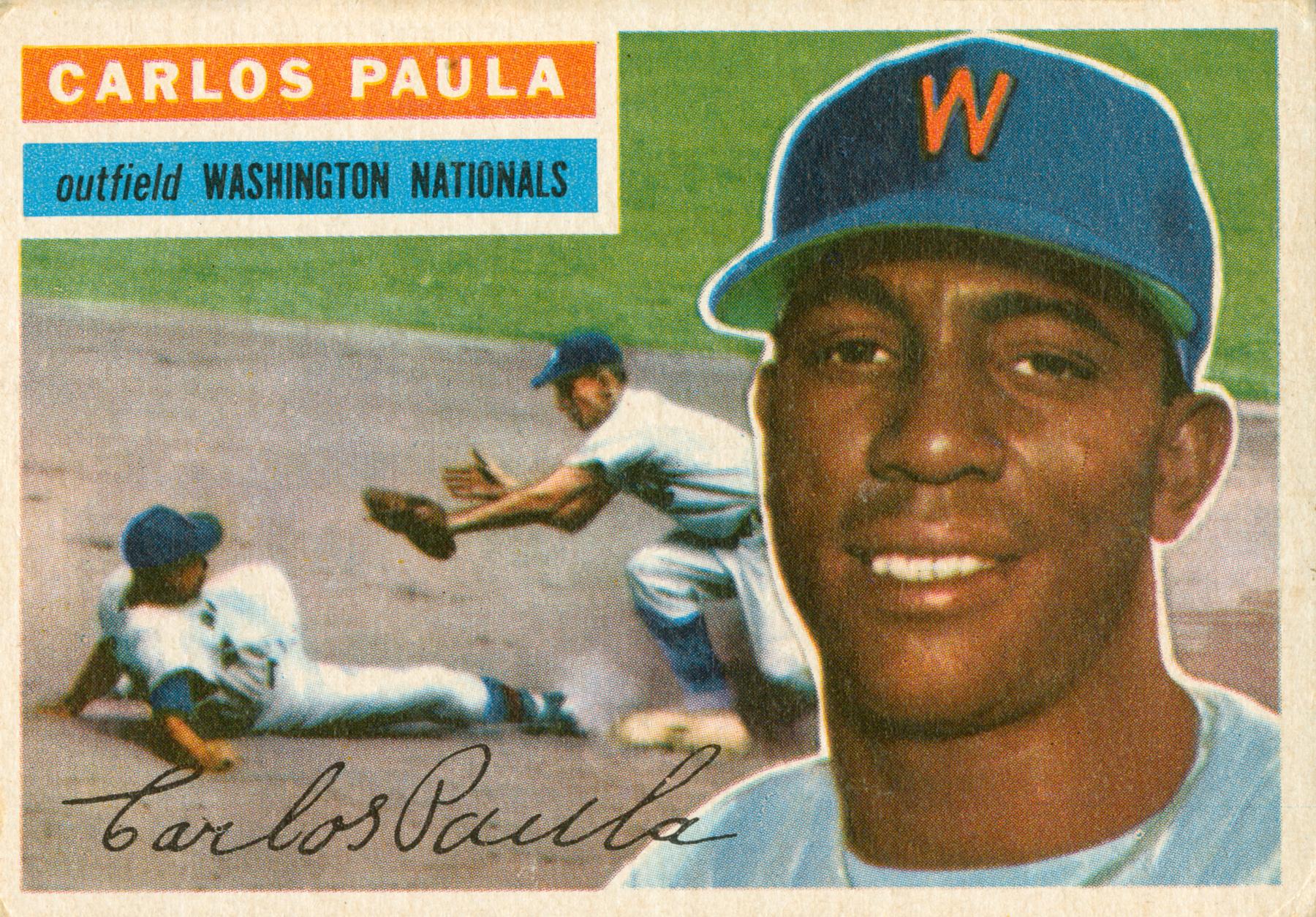

#GoingDeep: Carlos Paula, the man who integrated the Washington Senators

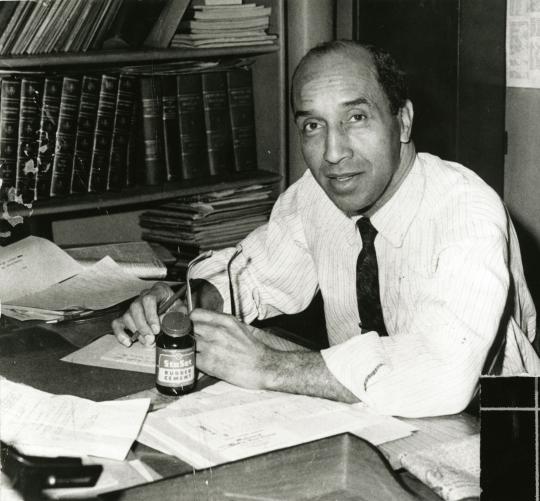

When the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum began its Digital Archive Project, one of the first collections digitized was the photographs of Osvaldo Salas – one of the most striking-yet-rarely-seen collections of baseball images known.

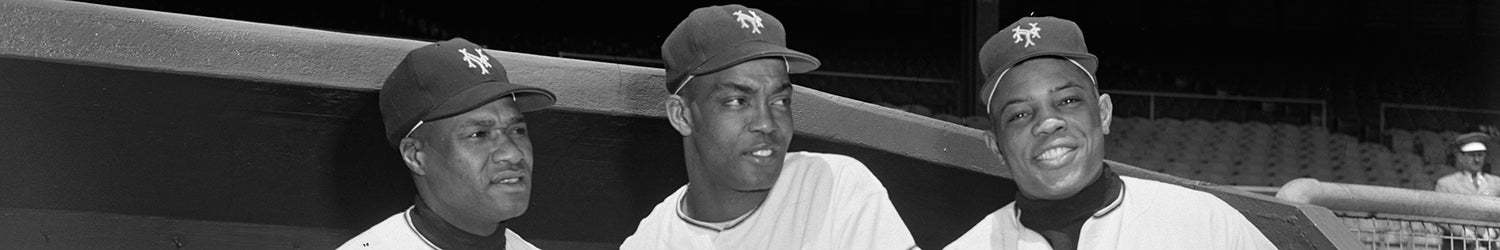

Salas was born in Cuba in 1914 and immigrated with his family to New York when he was 14 years old. He held a number of jobs before becoming a press photographer, whose images were published in Life and the New York Times. Salas loved baseball, and was especially interested in the Black and Latino players were who becoming the new face of baseball in the 1950s. Many of his photographs are currently on exhibit on the third floor of the Museum, including a rare portrait of a player named Carlos Paula.

Cambria scouted in Cuba under orders from the Senators' front office to recruit light-skinned Cubans. The year before, Senators Farm Director Ossie Bluege gave the written edict, “If he’s white all go and well, if not, he stays home.” Another time, Cambria was asked to confirm if a prospect was "snow white."

Teammates told the Post that Paula was the most exciting new player in camp, and Clark Griffith’s nephew and assistant farm director said “I saw him in Cuba this winter . . . Six-two, 200 pounds and runs like a rabbit. . . I saw him hit a line drive . . . [that] almost tore the glove off the outfielder.” But Harris tempered the enthusiasm: Paula had a hitch in his swing, he said. Paula chased too many balls low and away, he said. Paula wasn’t ready, he decided, and he sent the Cuban down to the Senators’ Charlotte Hornets farm team of the Class A Sally League.

The Post assured readers that Paula would be called up if any of the Nats’ outfielders faltered. But starting right fielder Tom Umphlett hit .219 in 1954 (with a .255 on-base percentage) and left fielder Roy Sievers wasn’t much better at .232, and Paula was nowhere to be seen. He stayed in Charlotte, leading the team in hits, doubles, triples and total bases, batting .309 and, if one local newspaper is to be believed, once launched a 559-foot home run.

The average newspaper reader, however, might not have noticed. Even the weekly Baltimore Afro-American gave Paula short notice. In a regular featured called "Tabbing the Stars," the paper updated statistics on Black ball players, from stars like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Monte Irvin, to players like Bob Thurman (who hit .217 in ‘55), Milton Smith (who'd hit .196 in 36 games then never play again), and Paula's fellow countryman Ramon Mejias (who finished 1955 hitting .216). But Carlos Paula’s name and numbers were never listed.

If the Afro-American ignored Paula, the Washington Post did something else. On July 20, after Paula had gone 3-for-5, the paper found fault with Paula's base running on squeeze plays. The next day, Paula homered, but the headline read "Paula's Lapse Allows Smith to Score from First Base on Single." On Sept. 20, a syndicated game recap opened with, "Washington’s rookie right fielder, Carlos Paula, was the Yankees’ best weapon in the night game, playing a foul-line line drive into a double in the three-run third and kicking a bases-loaded single allowing three runs to score, and misjudging a hard wallop into a triple in the six-run seventh."

Paula had only one hit in his last nine at bats in 1955, dropping his average from .305 to .299, finishing second on the Senators to Mickey Vernon’s .301. Still, he was named to the All-Rookie team, joining the likes of Elston Howard, Herb Score, and Ken Boyer. Then Paula was off to Cuba to play for Almendares, one of the most distinguished teams in Cuban winter ball, where he would hit .293 and be named an All-Star.

Meanwhile, in October, Bob Addie wrote another profile, this time for the Sporting News, though with some differences. Before Paula was described as a poor child in Cuba digging ditches and waiting tables; now Addie writes that “Paula’s boldest boast is that he has never had to work a day of his 26 years and isn’t about to get into such an enervating habit now.” Before he didn’t play baseball until 13; now Addie has Paula boasting that “when leetle keed, me great player” who admired “Baby Root and Lou Garage" and the "Yonkkiss" (Paula was seven when Ruth and Gehrig played their final season together). Addie again has a long section on Paula’s misplays, mentioning four occasions when Paula stood on third base, “fascinated” by a squeeze bunt, before finally deciding to run and being thrown out. (Game logs at Baseball-Reference.com don’t seem to bear this out.) The feature concludes with a quote from Dressen: “. . . he can throw, he can run, and he can hit. If I can only get him to think, he’ll be a star.”

When Paula returned to the lineup, the Post continued to focus on his miscues. On May 25, he went 2-for-4 with a home run and three walks, but the Post wrote, “Paula looked silly on White’s pop fly which fell for a double in the fourth. Carlos overran the ball . . . . Then he almost missed Goodman’s fly and dribbled the ball to second base. . . . Fortunately there was no score.” No errors were charged, and Washington won 10-5.

The highlight of Paula’s season would come on June 11, when his 3-run, pinch-hit homer in the bottom of the eighth inning gave the Nats a 4-3 victory over Kansas City. But the highlights were few, he played less and less, and his name began appearing in trade rumors. On June 24, he was optioned to Louisville (the Senators also optioned Harmon Killebrew on that day). Paula was hitting .171, though seven of his eight hits were for extra bases.

Where Dressen stopped, the Post picked up: “It seems the reason Paula gets shuttled back to the minors is because he believes baseball is a sport and not a serious business.” As an example, it brings up Paula’s two-day delay in returning from Cuba when his mother was ill. Instead of being contrite, Paula is said to have blamed the delay on the two-hour time “deeference." He was said to have returned only due to the threat of a “beeg fine.” Probably Addie is conflating Paula’s delay from Denver to Chicago, which, unlike Cuba and Florida, does have a two-hour time difference. Either way, the Post added explicitly that Paula’s English was poor.

Once again, before the season started, Paula was optioned, this time to Minneapolis, where Paula would remain invisible, his hitting feats mentioned only in single-sentence updates in the Post: .400 batting average in May; .355 in June; .335 in July. By the end of the year, Paula had dropped to .288.

At Sacramento, Paula led the team in batting average (.315) and slugging percentage and was second in total bases and home runs. When the season ended, as always, he returned to Cuba to play with Almendares. That winter, however, would be different. The winter of 1958-1959 brought revolution to Cuba, and on Jan. 1, Fidel Castro’s forces overtook the capital, and baseball was suspended.

On March 12, 1961, the Post ran an update on Paula under the headline “Paula May Face Death.” The two-sentence item reads, “There’s a report that Carlos Paula, Washington outfielder of a few years ago, is under a death sentence in Cuba . . . Paula, who had a brother who was executed by Castro when the latter first took office, allegedly was jailed for beating up several of Castro’s men.” No updates followed.

In 1964, the Sporting News reminisced, “Paula was among the most homesick of the lot [the Cuban players]. He was always inventing stories about having to go back home. He must have had a half-dozen grandmothers die suddenly.” Other than the occasion when his mother suffered a heart attack, there are no contemporary reports of Paula leaving a team to go to Cuba.

In 1966, the Boston Globe reported that “for several awful moments it looked as though the Dodgers had Carlos Paula – Washington’s old catch-nothing outfielder – playing center field.”

The jokes did not: in 1975, the Boston Globe described an error-filled game as “a chapter from Carlos Paula’s autobiography.” In 1976, the Globe mocked the Angels’ outfielders by saying “Carlos Paula could have played center on this team.” In 1978, a poor fielder was called a “reborn Carlos Paula.” In 1979, the Washington Post said a game that featured poor base running should be “dedicated to the memory of Carlos Paula.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In 1982, the Globe trotted out two Paula jokes, the last being that a game seemed to be played by “eight guys named Carlos Paula.” By this time, Carlos Paula had been out of the Major Leagues for 26 years; the sportswriter of the article had been 11 years old when Paula had last played.

Carlos Paula had gone from rumor, to character, to cartoon. Yet the person remained invisible, reduced to Black and white numbers in box scores and mentions in brittle, Black and white newspapers.

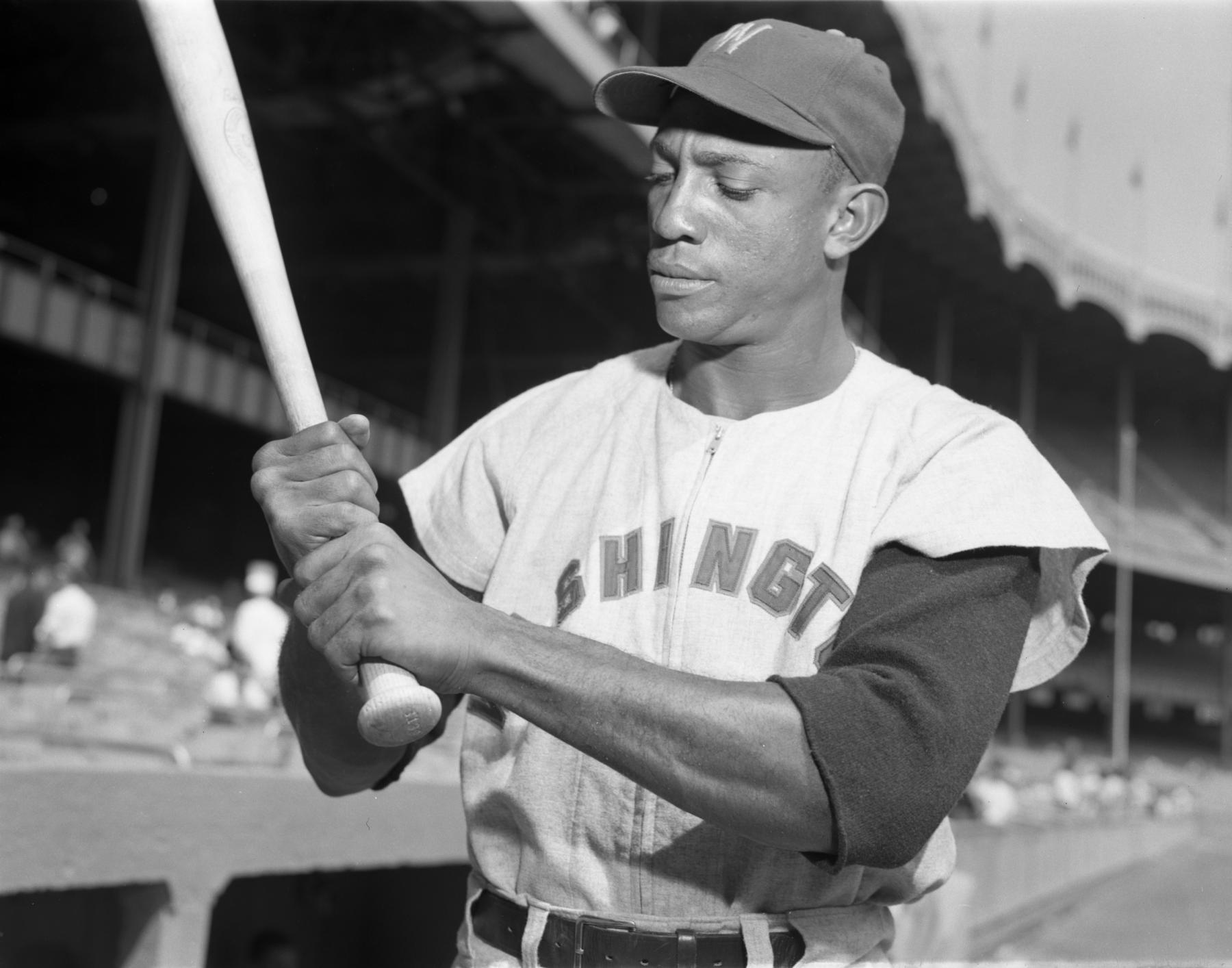

But then there is this: the photograph, taken by Osvaldo Salas, who, like Paula, was born in Havana, and who documented the lives of players who were pioneering the integration of baseball.

His rare portrait of Carlos Paula is Black and white, but with all the rich gradations of gray. Paula wears Washington's road gray uniform, with a zipper-front jersey and two-tone, felt lettering. He stands, framed by the façade of Yankee Stadium, gripping a bat. His forearms are rippled with muscles. He looks down at his hands. His face is strong and somber.

On June 15, 1983, the Washington Post's sports ticker included, at the very end, this note: “Carlos Paula, who in a short span as a Washington Senator achieved inordinate notoriety for his adventurous outfielding (while batting .299 in 1955), died recently in Miami. He was 54.”

The item raises more questions than it answers. Paula's death certificate is equally incomplete; there is no cause of death. It lists his marriage status as "unobtainable." Parents' names, "unobtainable." Occupation, "unobtainable."

Two days later the Washington Post included an addendum: “P.S. on Carlos Paula, who died recently in Florida: he was the Senators’ first Black [player].”

Larry Brunt was a digital strategy intern in the Hall of Fame's Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development