- Home

- Our Stories

- Forgotten History

Forgotten History

“One summer day in 1939 a kid squatted on the bank behind home plate at Russell Field in Warren, Pennsylvania, fielding foul balls (which could be redeemed for a nickel each – no small consideration in those days), and saw Josh Gibson hit the longest home run ever struck in Warren County. It was one of many impressive feats performed by touring Black players that excited the wonder and admiration of that foul-ball shagger. This book is the belated fruit of his wonder.”

Bob Peterson

Preface, "Only the Ball Was White"

Given the vast body of literature that seems to cover every aspect of our National Pastime, it seems curious the story of the Negro Leagues has only recently become part of the published record.

In fact, it is not just the Negro leagues but African-American baseball history in general which was hidden from view for many decades. When one examines the written record of baseball history, the historiography of Black baseball presents an astounding chronology.

African-Americans have been playing baseball as long as any other segment of American society. But prior to 1970, the published record of this participation is extremely weak. While bits and pieces of this story can be gleaned from early newspaper accounts, the initial attempt to relate this story in book form occurred in 1907 when future Hall of Fame inductee Sol White published Sol White’s Base Ball Guide, also known as the History of Colored Base-ball. The original print run is not known, but only a handful of copies presently exist, including one in the library collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.As far as books are concerned, that’s about all there is until 1970 when Robert Peterson published Only the Ball Was White, a groundbreaking piece of baseball literature if ever such existed. But surely, there must be something about Black baseball between 1907 and 1970, a span of more than six decades. After all, there are hundreds of new baseball books produced every year and there is no way that this topic could have been completely ignored for that long.

Unfortunately, for both historians and baseball fans alike, the written record is surprisingly scant.

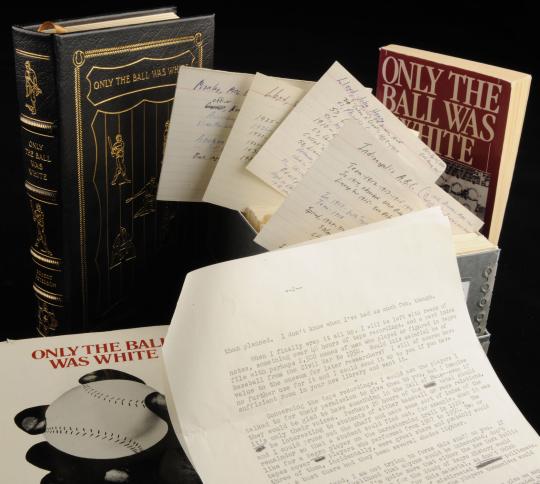

Collage of materials collected by the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library on the book "Only the Ball Was White." (Milo Stewart, Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

The most relevant sources of material are the Negro newspapers. Most historians are knowledgeable of the variety of newspapers which were dedicated to the African-American audience in most large urban areas. Some of the more notable being the Afro American (Baltimore), the Amsterdam News (New York), the Chicago Defender, and the Pittsburgh Courier. These publications served as record-keeper of the African-American communities, and were the cradle for some of baseball’s early Black sportswriters such Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith. Baseball was one of the most important forms of recreation in America during the period from 1910 to 1940s and this is reflected in the sports coverage of these papers. The Golden Era of the Negro Leagues occurred during the 1920s and 30s, and it only via these newspapers, often relegated to obscure collections and microfilm reels at major research libraries, that one is able to rebuild this story.

Other than these newspapers, the mainstream media did not publish any widely available account of the Black baseball story.

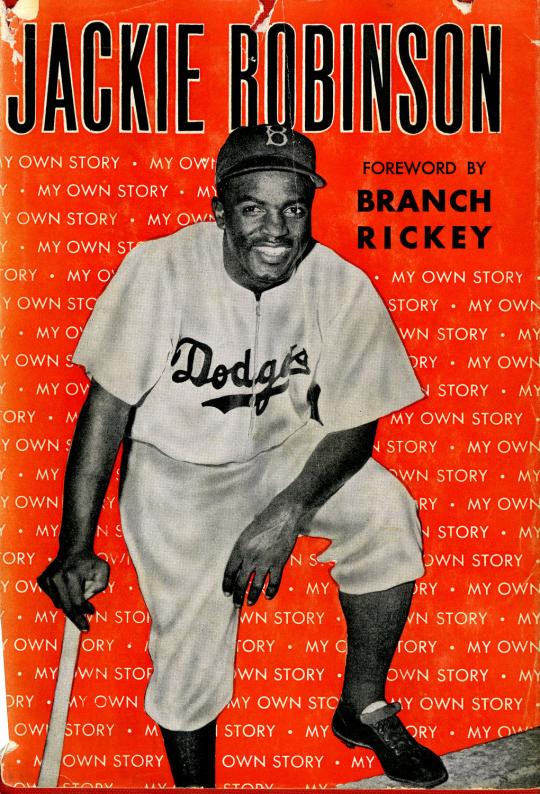

While the Negro newspapers are the best source of material for several decades, an interesting turn occurred in 1947 when Jack Roosevelt Robinson entered Major League Baseball as a rookie for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The story had such an impact on the African-American community that the local newspapers began to focus almost exclusively on the major leagues, with coverage of the Negro Leagues diminishing over time, mirroring the actual demise of the leagues themselves. For historians, this means that their best source of material now becomes less important as the papers changed their focus to what had been an exclusively white game.

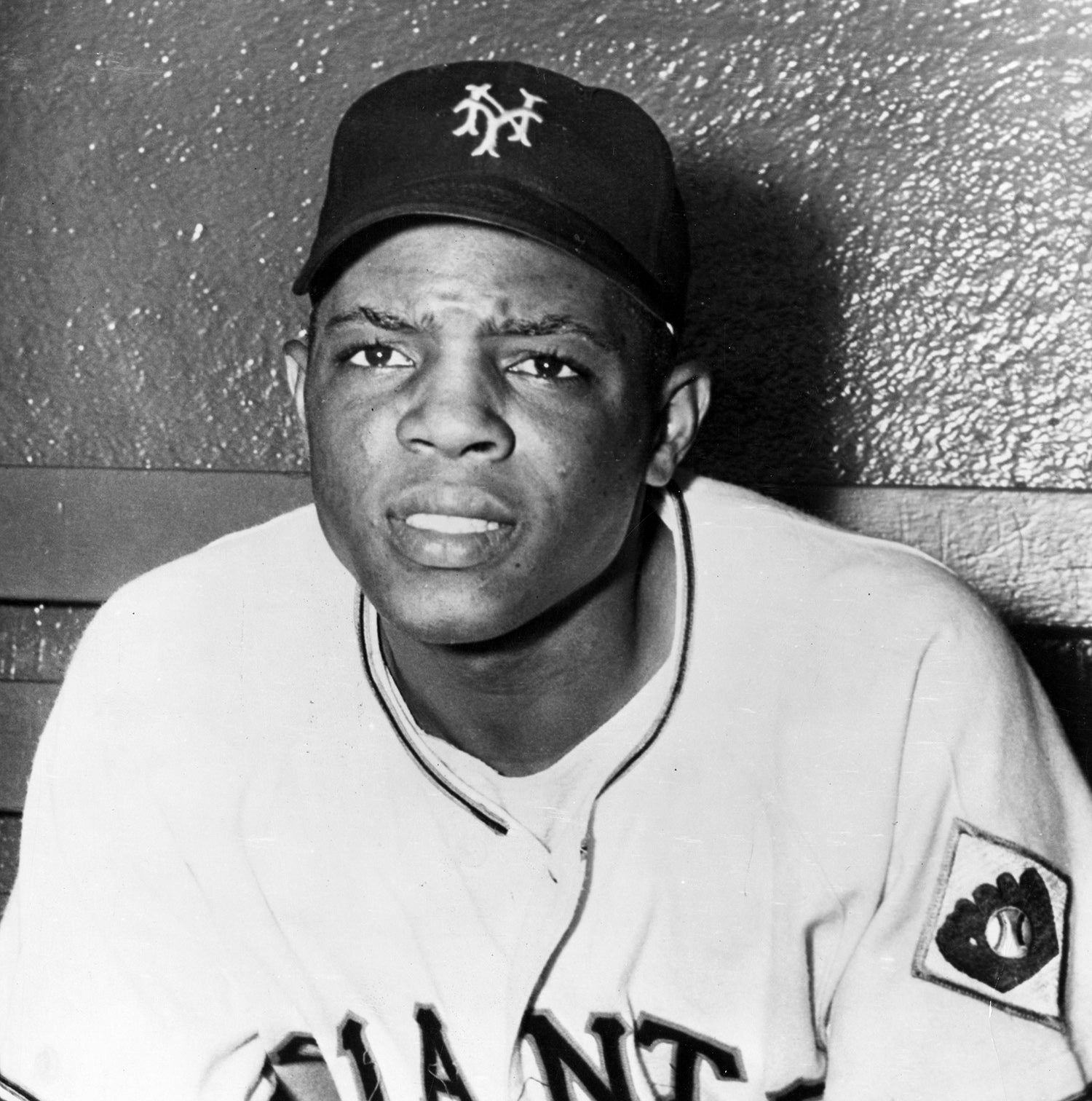

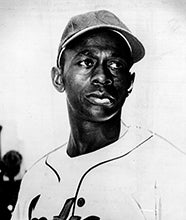

From 1947 to the 1960s there was a small body of material which made its way into the bookstores, as a number of biographies were published. These focused mainly on Jackie Robinson, but also included some of the other early Black ballplayers like Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Satchel Paige. However, these books tended to cover the personal stories of these men and did not spend a great deal of time reviewing the history of Black baseball. Once again, the historic record remains hidden from view.

In 1970, this all began to change. Robert Peterson grew up in Warren, Pa., and recalled seeing barnstorming games which incorporated a variety of teams, including some from the Negro Leagues. Operating as a freelance writer, be began a research project on the history of Black baseball in 1966. Not only did his inquiry lead him through a collection of old Negro newspapers, but he was able to track down a number of star players whom he interviewed at length.

Peterson also made use of the library at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as can be seen in a small collection of correspondence that dates from 1968. He had become acquainted with Hall of Fame Historian Lee Allen and he relied on Allen’s help in tracking down photographs and other information on early Black ballplayers.

The result of the process was Only the Ball Was White, a work that opened the door to a lost element of American history. No one, including Peterson, could have foreseen the impact of this book on baseball research. This was the first attempt by the mainstream media to relate the wonderful story of early Black baseball and the public was fascinated. For many young Americans who had never heard of the Negro leagues, it was an eye-opening presentation on part of baseball which they simply had never been told. The Negro leagues were not part of school curriculum and there were no other books about the topic, so here it was, finally laid out for everyone to read…and the flames of historic inquiry had been fanned for everyone else to enjoy.

Various publications and organization have, from time-to-time, put together lists of the top sports books or top baseball books, and Only the Ball Was White always makes the list. This is the book that served as the key to the door which opened up a room long neglected.

Since the door opened, there has been a wonderful body of literature produced from all corners of the country. Professional writers, academics and baseball historians have picked up on the challenge, and now an excellent selection of titles exist to which can be referred to when seeking information on this segment of the American cultural fabric.

While it is sad that Black baseball was ignored for so many years, there is one critical silver-lining to this cloud. Because the vast majority of the written record of African-American baseball history has been published since 1970, it is quite easy for a public or college library, along with individual readers, to build a comprehensive collection of just about everything that has been released. Writers like Larry Lester, Leslie Heaphy, John Holway, Larry Hogan, Adrian Burgos, Neil Lanctot, Rob Ruck, Phil Dixon, Jules Tygiel, and many others have published a steady stream of new material, which have begun to examine the nooks and corners of Black baseball in the same fashion that that white baseball received from earlier generations of writers.

Bob Peterson, in his own letters, clearly indicated that he did not understand the eventual impact of his work, as he tried to coordinate with Lee Allen to donate his research notes to the Hall of Fame archive stating, “Understand, I am not trying to force this stuff on you. If you see little likelihood that anyone would be interested, don’t hesitate to say so.”

Fortunately, Allen said yes and Peterson’s research rests safely in the archives, carefully stored for future generations of library patrons who may seek to tell more of this story.

Jim Gates is the Librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Spink Award Winners

Related Stories

Mark McGwire to be considered by Today’s Game Era Committee

Jack White's Hall of Fame Tour

Update on Hall of Famer Rod Carew

Keep Baseball Going

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr01a

Sound on Paper

Sandberg to Host Otesaga Hotel Seniors Open Pro-Am

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr_1972_08_14b

01.01.2023