- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

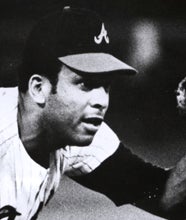

How prominent were Wally Moon's eyebrows? So prominent that from a distance, it looked like he was wearing horn-rimmed glasses.

In actuality, Moon’s eyebrows consisted of one long eyebrow. There was no stopping point in the middle. The eyebrow was not only continuous, but it was quite dark and very full. It was a distinctive look, one that was captured on many of Moon’s Topps cards, but none better than his 1963 card.

All ribbing about eyebrows aside, Moon was a good looking ballplayer. He had chiseled features, a thin face, and kept his hair short and neat. Wearing the dignified home uniform of the Los Angeles Dodgers, along with that always majestic blue cap, Moon looks like the poster child for a ballplayer of early 1960s vintage.

The 1963 set was also one of the best sets that Topps produced. Most of the player cards featured two full photographs of the player on the front of the card: the large color picture that occupied the top four/fifths of the card and a smaller black-and-white inset photo contained within a circle that was either blue, orange, red or yellow (as in the case of Moon). The player’s name, position and team are then set against a contrasting color background (green, gold, yellow, blue, or red—as with Moon’s card), completing a three-pointed, multi-colored card. All in all, this was a classic set, one that remains highly popular with collectors who love their vintage cards.

Wally Moon may have taken some teasing from his teammates about his 1963 card and his eyebrow that summer, but no one kidded him about his hitting. That was something that he always did well, going back to the day in 1950 when the St. Louis Cardinals signed him as an amateur free agent. Four years later, he showed up to the Cardinals’ spring training camp. Moon had already determined that if he did not make the Redbirds’ Opening Day roster, he would head back to his native Arkansas and take a teaching job that he had been offered. A graduate of Texas A & M, the well-studied Moon had already acquired his Masters Degree in teaching. He was ready to pursue his second career.

That second career would have to wait. Moon not only made the team in the spring of ‘54, but he played so well in Florida that the Cardinals traded Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter to the New York Yankees and anointed Moon their starting center fielder. For Moon, this was a bittersweet development. “I signed with [the Cardinals in the first place],” the soft-spoken Moon explained to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “because they were my favorite team and Slaughter my favorite player. I admired the way he hustled and how hard he played.”

So did Cardinals fans. They did not react well to the trade; they loved Slaughter and resented Moon for taking his job. Quite unfairly, they booed Moon during the team’s Opening Day parade at Sportsman’s Park.

As Moon strode to the plate to take his first big league at-bat that day, the fans chanted “We Want Enos.” Moon quickly silenced the chorus by blasting a home run over the right field pavilion.

Although Moon’s power level fell off during the season—he finished with a modest total of 12 home runs—he otherwise emerged as an offensive force. He hit. 304, drew 71 walks, and posted an OPS of .806. Such numbers helped him win the National League Rookie of the Year Award.

Moon would only get better over each of the next three seasons. By 1957, he began to solve left-handed pitching, raised his OPS to .875, and earned his first All-Star Game selection. He also reached a career high with 24 home runs. There was every reason to believe that Moon would remain a mainstay in the Cardinals’ outfield for years to come.

Then came the roadblock of 1958. In May, Moon collided with Joe Cunningham (who was playing out of position in left field) as they pursued a fly ball off the bat of Orlando Cepeda. Moon suffered the worst of it, sustaining an injured elbow. He missed some time, and even when he returned to the lineup, the elbow injury affected his batting stroke.

Moon finished the season with dreadful numbers: seven home runs and a .238 batting average. The Cardinals’ front office placed the blame of a disappointing season on Moon and slugger Del Ennis, who was nearing the end of his career. That winter, the Cardinals made a trade, sending Moon to the Dodgers for outfielder Gino Cimoli.

The trade crushed Moon, who loved living in the St. Louis area with his wife and children. He also felt insulted that the Cardinals had included another player in the deal, implying that they did not even consider him the equal of Cimoli.

As rejected as Moon felt, the Dodgers loved their new acquisition, praising him for the maximum effort with which he played. Putting aside his struggles in 1958, the Dodgers made Moon their starting left fielder in 1959. Moon now had to deal with the challenge of playing his home games at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the home of the Dodgers since their recent move from Brooklyn. With the right-center field gap 440 feet away, Moon wondered how he could possibly hit home runs in his new park.

Ever the thinking man’s player, Moon discussed the situation with Stan Musial, his former teammate in St. Louis. Musial suggested that Moon alter his batting stance and try to push pitches toward left field at the Coliseum, which featured a 42-foot high screen, but where the distance to the foul pole was only 251 feet. Moon started using an unconventional inside-out swing and began lofting the ball toward left field. The Sporting News later referred to him as “Wrong Way Wally” because of his unusual opposite field stroke. Some writers described his home runs as “screenos” because of the strange way they cleared the enormous left-field screen.

Yet, the term "screenos" never really gained traction. Moon’s opposite field home runs soon became known as “moon shots.” Moon remembers a legendary Dodgers broadcaster as being the source of the new baseball term. “Our announcer, Vin Scully, was really the one who started it,” Moon recalled in an interview with the Akron Beacon Journal. “Remember back then that everyone was really interested in space shots [the space race], and when Scully started calling my opposite field home runs ‘moon shots,’ it really caught on.”

The moon shots weren’t hit far, but they had the necessary height. For the season, Moon hit 19 home runs, with 14 of them coming at the Coliseum. He also piled up a league-leading 11 triples, batted .302, and finished fourth in the MVP race. Additionally, he helped the Dodgers win their first World Series in Los Angeles. A few days after the Dodgers wrapped up the title in six games over the White Sox, Moon happened to run into U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon during a stopover at the Dallas airport. Nixon, an enormous fan of the game, walked over to the airport celebrity room, congratulated Moon on the world championship, and talked baseball with the Dodgers’ star for several minutes.

Moon remained productive over the next two years, coinciding with the Dodgers’ final two seasons at the Coliseum. He was at his best in 1961, when he batted .328 and led the league with an on-base percentage of .434. The Coliseum helped Moon without a doubt, but he never felt completely comfortable playing in that location. “The Coliseum was good to me,” Moon told sportswriter Melvin Durslag, “but at no time did I ever feel normal there. This is understandable, because everything I did in the place was abnormal. I changed my batting stance and my fielding habits and never played the way I was trained to play.”

Moon made those comments in March of 1962. When the franchise moved into the new pitcher friendly Dodger Stadium later that season, Moon struggled. Appearing in 95 games, he hit only four home runs and battered a meager .242.

Moon played more in 1963, the year that this Topps card came out, but was now 33 and continued to scuffle in the batter’s box. He would play two more seasons as a backup outfielder, a role that he fulfilled through the 1965 World Series. The Dodgers won the Series over the Twins in seven games, but Moon came to bat only two times, leading to dissatisfaction with his second-string status. After the Series, he asked the Dodgers to trade him. They could find no takers. Rather than return for another season of fill-in duty, Moon opted for retirement.

Even after his playing career, Moon remained active—both inside and outside of the game. In 1969, the expansion San Diego Padres hired him as part of manager Preston Gomez’ inaugural coaching staff. Moon then left the job after only one year, so that he could return to his previous post as athletic director at John Brown University.

Away from baseball, Moon also became involved in politics. A staunch member of the Arkansas Democratic Party, he helped run successful campaigns for Senator John McClelland and Governor Dale Bumpers. Moon also served on a committee for a local amendment aimed at revamping county government.

Through his various pursuits, Moon accrued enough wealth to become the owner of the minor league San Antonio Dodgers, LA’s affiliate in the Texas League. He operated the franchise for three seasons before selling the team.

He passed away on Feb. 9, 2018.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

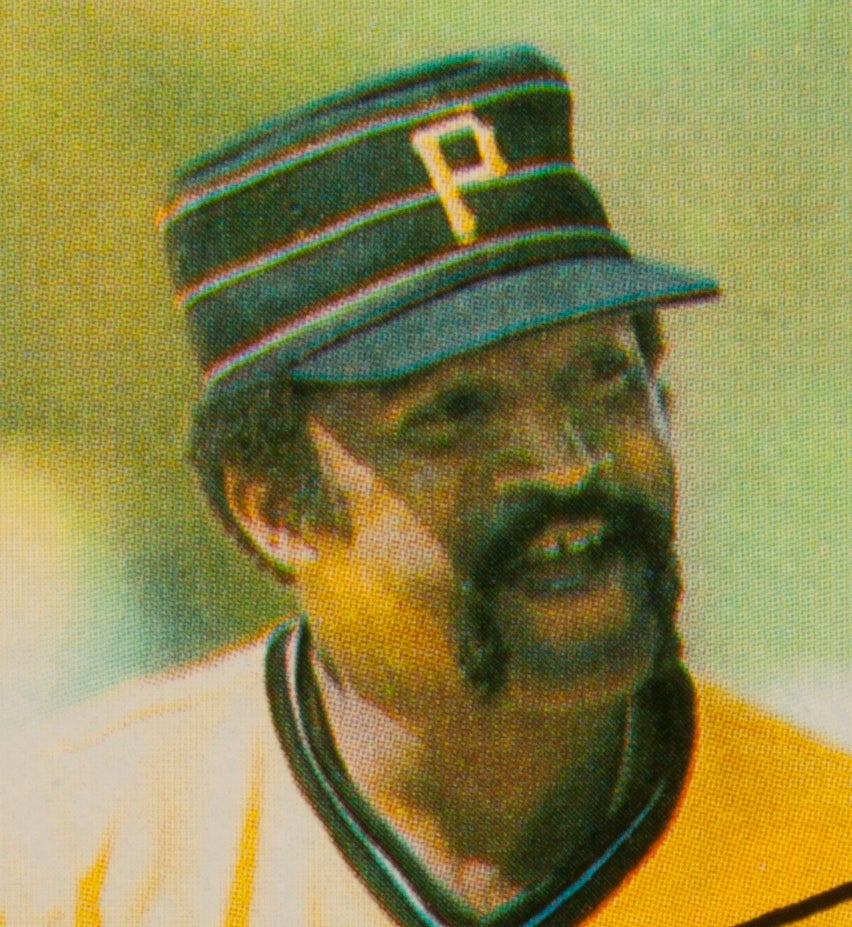

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

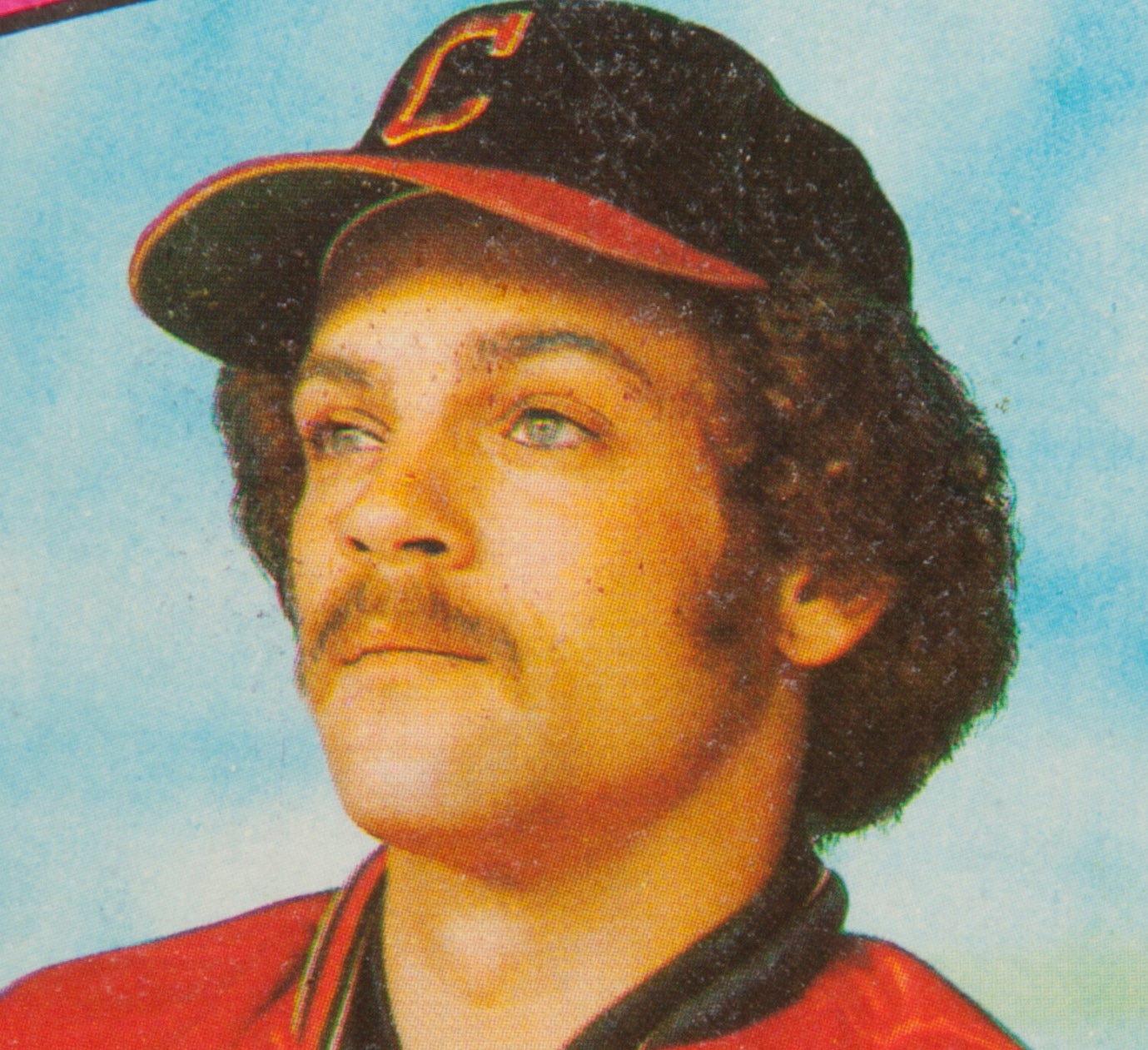

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

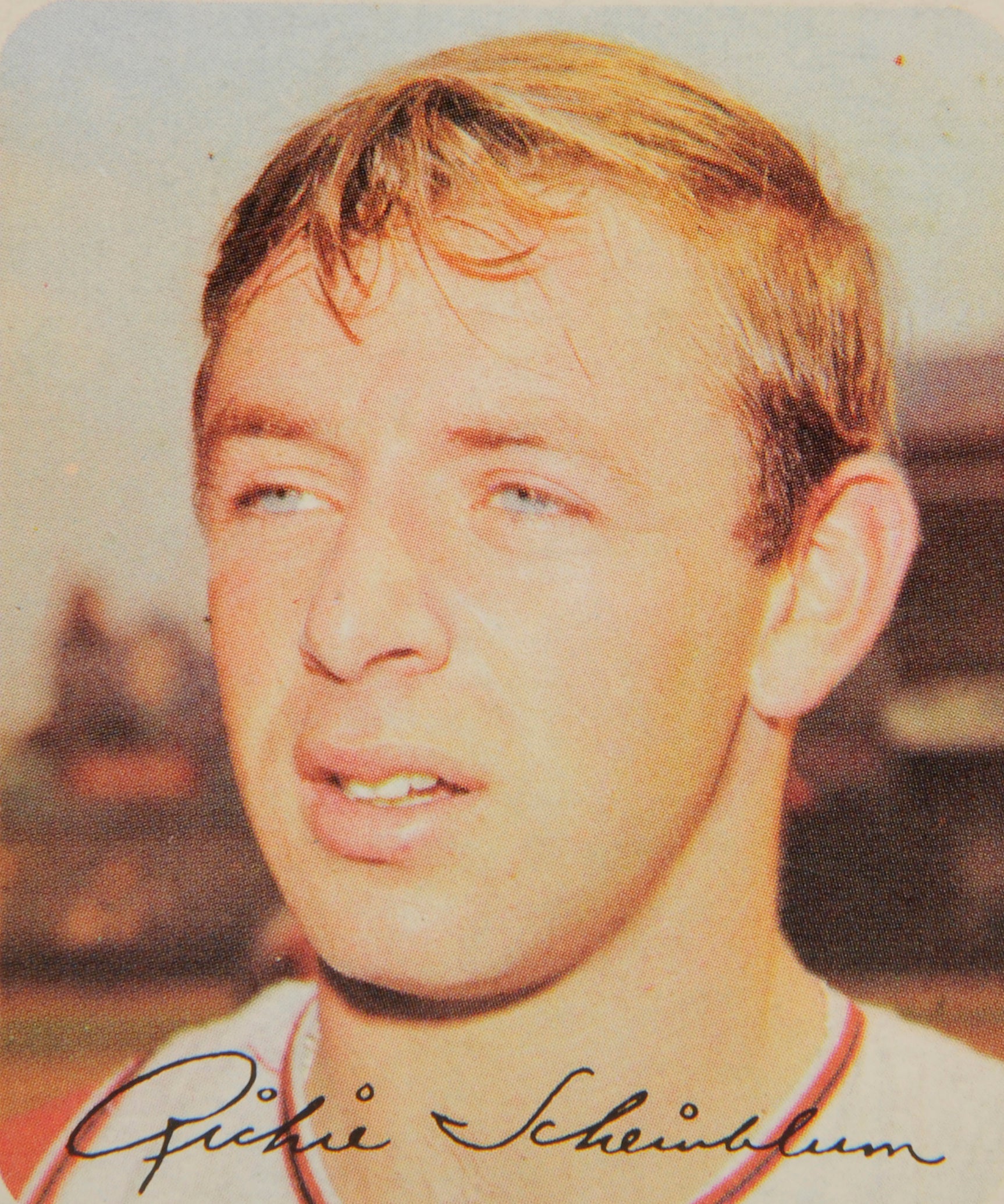

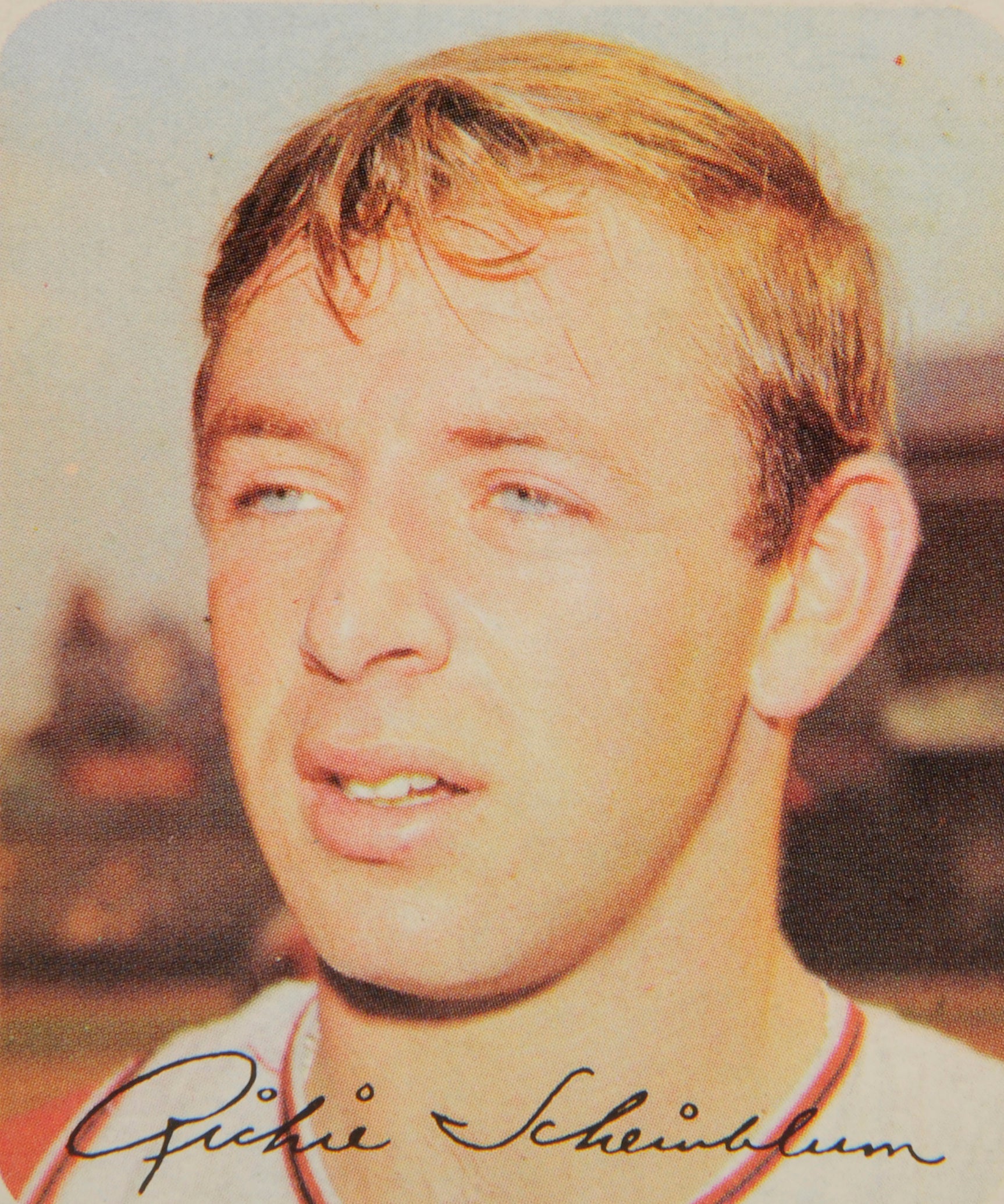

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Bill Veeck holds ‘Grandstand Managers Night’

1951 Hall of Fame Game

Treasures from Cooperstown Coming to Capital Region for Tri-City ValleyCats Game on Wednesday

The Winter of Baseball Life

Hall of Fame Weekend 2017 to Feature Inductions of Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez, John Schuerholz, Bud Selig, July 28-31 in Cooperstown

He Never Complained

Hall of Fame to Host Holiday Celebration Saturday

Larkin and Santo join baseball’s elite

1989 Hall of Fame Game

A Road to Equality

Museum’s Authors Series Programs Bring Latest Baseball Stories to Cooperstown

01.01.2023

Integration Files (BA MSS 67)

01.01.2023