- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

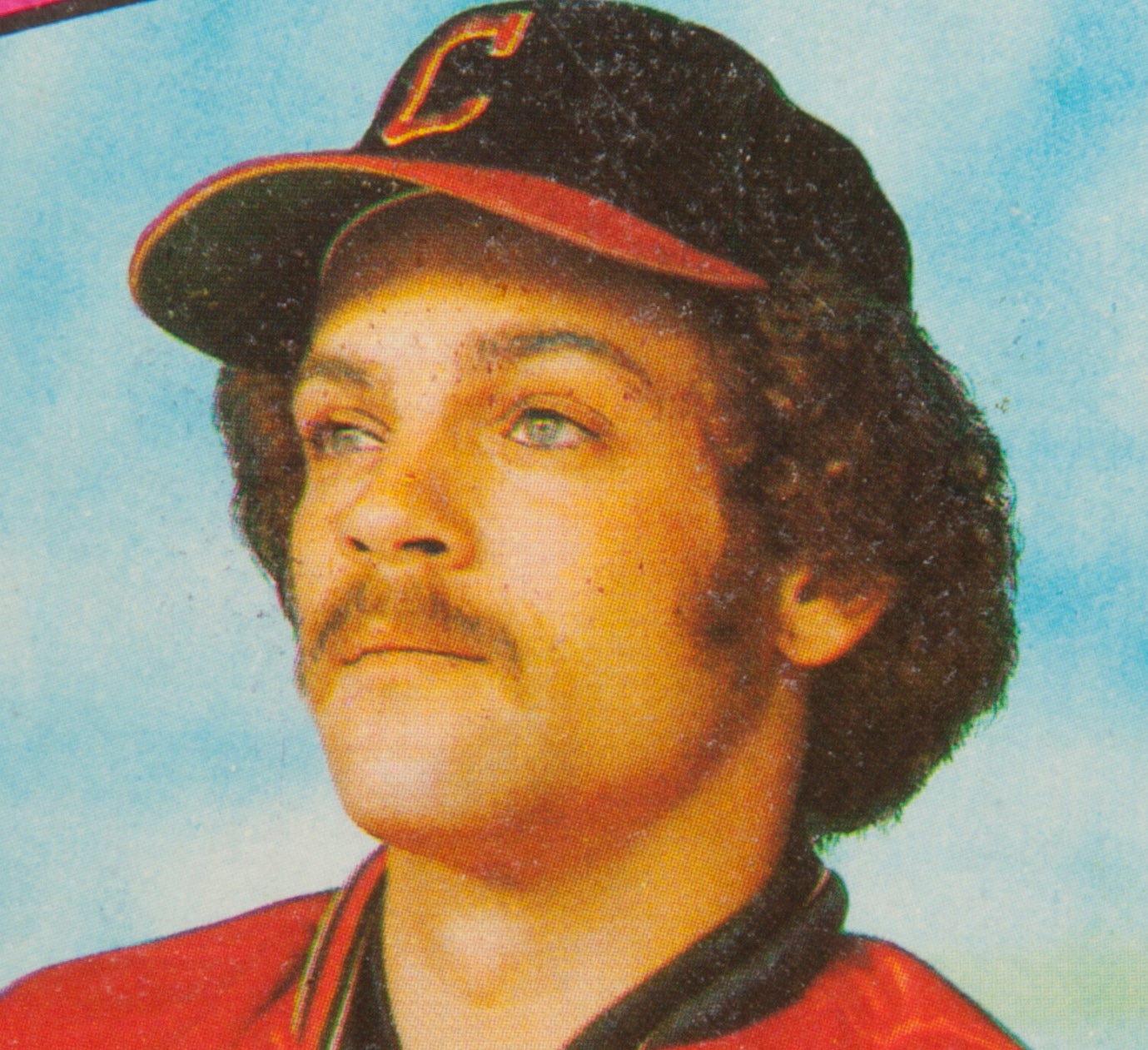

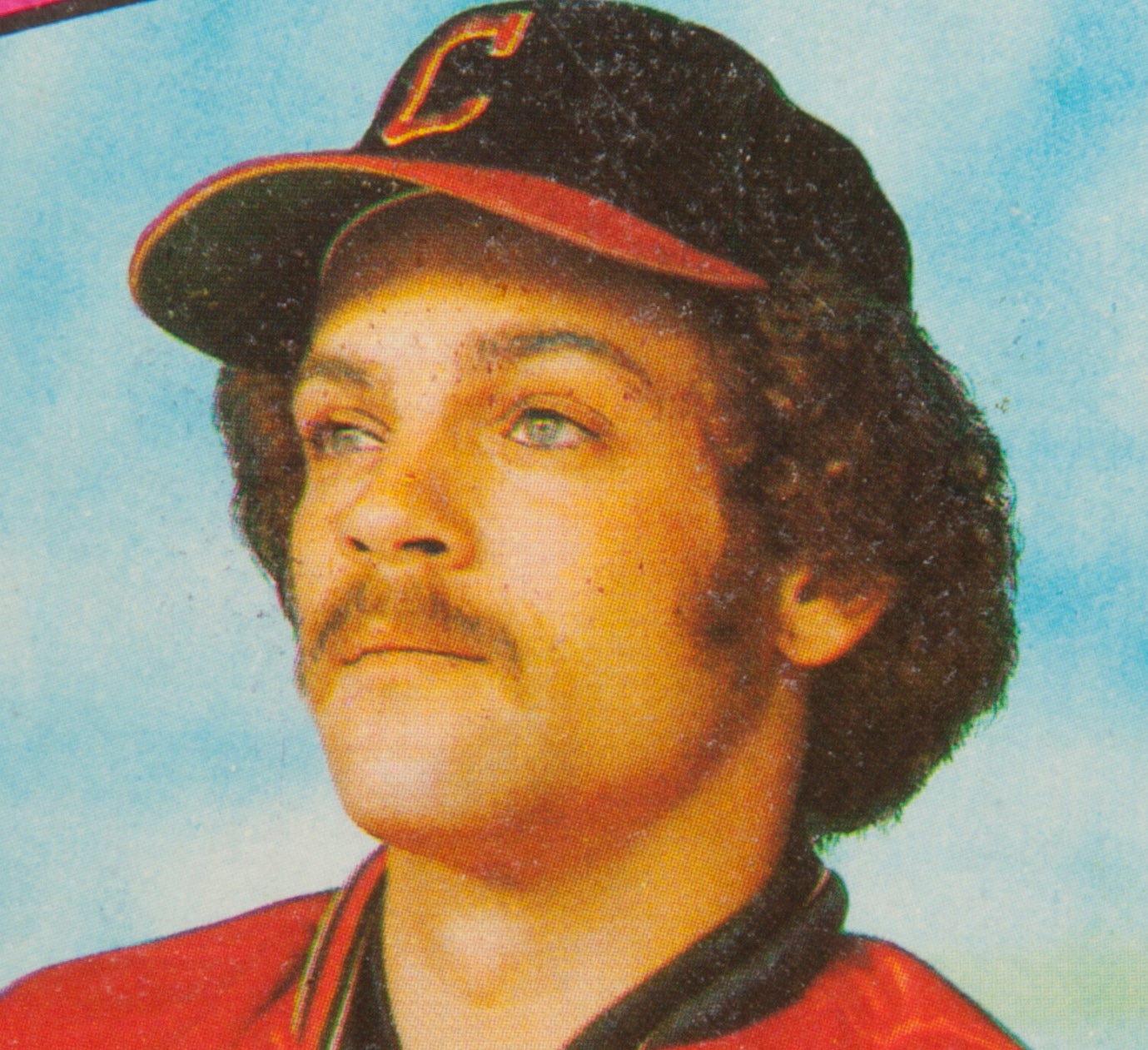

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

It is most fitting that Luis Tiant’s second-to-last Topps card, issued in 1982, shows him wearing the ridiculously gaudy gold and black color scheme of the Pittsburgh Pirates. At the time, no other team looked like these circus performers, as did those last vestiges of the “Pittsburgh Lumber Company.” The Pirates sported the black and gold in every imaginable combination—gold tops with black pants, as seen here, or black tops with gold pants, or sometimes black tops and black bottoms, or an all-gold look that made the Pirates look as luminous as Wrigley Field on a sun-splashed day.

In a way, Tiant was a circus act on the mound. With his full windup, the hesitation in his delivery, the 180-degree spin that found him looking squarely at second base, and the willingness to throw the ball from a variety of angles, Tiant brought the flying circus to the pitcher’s mound every time he stepped onto the playing field.

Other than his whirling dervish routine on the mound, another thing that comes to mind with Tiant are those horrendous but humorous hot dog commercials he once filmed in the 1980s. Tiant couldn’t act, but his heavy accent, over-the-top delivery, and willingness to make fun of himself made New York Yankees broadcasts more enjoyable back in 1979 and ‘80. When I think of Tiant, I also tend think of those old newspaper images that show him shirtless, soaking in a hot tub and smoking an enormous cigar. (According to eyewitnesses, Tiant also used to take cigars into the shower with him, which makes me wonder how he kept those cigars from being doused by the hot water.) Tiant always seemed to have something in his hand, whether it was a hot dog, a cigar, or a baseball, as we see him holding on his 1982 Topps card.

When Tiant made his major league debut for the Cleveland Indians in 1964, the native of Cuba fulfilled a dream of playing in the big leagues, completing an ascent that had begun with a stint in the Mexican League. After spending the summer of ’61 in Mexico, Tiant had planned to return home to Cuba, but Fidel Castro banned all outside travel, effectively preventing Cuban athletes from seeking careers elsewhere. Tiant’s father told him not to come home to Cuba; if he did, he would be trapped on the island.

Tiant wanted to pitch in the major leagues, not the Mexican League. It was a goal that inspired him more than most. He felt particularly motivated after his equally talented father was denied major league entry because of the darkened color of his skin. Luis Tiant, Sr. was a respected left-hander who forged a representative career in the old Negro leagues during the summers and the Cuban League during the winters. Fiercely competitive and armed with a herky jerky delivery, the elder Tiant deserved a bigger stage, but the shameful wall of segregation kept him from ever achieving his own major league dream.

Prior to the 1962 season, the Indians purchased Tiant from the Mexico City Tigers. Two years later, he made the major leagues. As a rookie in 1964, the junior Tiant proved that he belonged. Pumping fastballs with his potent right arm, Tiant won 10 of 14 decisions and posted a 2.83 ERA. The following year, he hurled three shutouts and became a fulltime member of the Indians’ rotation.

Tiant remained a solid No. 2 starter until 1968, when he vaulted himself into the elite class of American League pitchers. Achieving one of his first tastes of national stardom, Tiant was featured on the cover of The Sporting News, the renowned “Bible of Baseball.” Although the summer of ’68 became known as the “Year of the Pitcher,” Tiant’s numbers transcended the context of the era. Tiant spun a league-leading ERA of 1.60 and held opposing hitters to a .168 batting average. Even in the dead ball era, which was not all that different from the season of 1968, those numbers would have remained impressive.

Not coincidentally, the 1968 season also marked the unveiling of El Tiante’s unique set of deliveries. Debuting his new pitching motion against the California Angels, he first began to use his exaggerated pirouette windup. Tiant began to incorporate the strange delivery more and more often, making it a regular part of his already diverse pitching repertoire. On days when his fastball and various breaking balls lacked their usual snap, an innovative Tiant found himself turning to an even wider array of his unusual wind-ups, which included the spinning torso, head-turning bobs, and assorted other machinations.

Though it’s hard to say with any certainty, Tiant’s unusual motion may have also contributed to an injury that nearly ended his career. After being traded to the Minnesota Twins—as part of the six-player deal that brought Graig Nettles to Cleveland—and starting the 1970 season with six consecutive wins, Tiant actually broke his shoulder blade while making a start in late May against the Milwaukee Brewers. According to Tiant, the doctor claimed that he had never seen such an injury experienced by a pitcher. In fact, the doctor had only seen one broken shoulder blade in all of his years treating athletes. It was suffered by a javelin thrower, and not a ballplayer.

Missing most of the summer while recovering from the unusual injury, Tiant returned to the Twins in August, lost three of his four remaining decisions, and then struggled so badly in the spring of 1971 that he drew his unconditional release. On the eve of Opening Day, Tiant was unemployed.

Only three seasons removed from a 21-win season, Tiant was desperate for a job. In April, the Atlanta Braves agreed to give Tiant a shot, but only with a minor league contract. The minor league tryout lasted about a month; he did not pitch well and drew his release, and thus never made an appearance for the Braves. With two releases by two different organizations in the same season, Tiant’s career bordered on the edge of oblivion.

With the vultures circling around his damaged right arm and shoulder, Tiant received a last-chance opportunity with the Boston Red Sox, who agreed to give him a minor league deal in May. For an organization often criticized for its inability to develop pitching, the signing of Tiant would represent the deal—and the steal—of the decade. Within a month, Tiant found himself back in the major leagues. Though he won only one of eight decisions, he showed the Red Sox enough to warrant a roster spot in 1972. That year Tiant made a stunning comeback, leading the league with a 1.91 ERA while spinning a half-dozen shutouts.

By 1976, Tiant had accumulated three 20-win seasons for the Sox. Long since removed from being a power pitcher and actually somewhat past his prime in 1975, he reached the pinnacle of his fame by tossing a shutout and a complete game in two of his 1975 World Series starts against the “Big Red Machine.” In Game Four, he treated a nationwide fan base to a first-hand display of his on-the-mound gymnastics. “He jiggles his glove, he throws back his head, shakes his leg, twists around, and all of a sudden, here comes the ball,” said Hall of Famer catcher Carlton Fisk in an interview with Ron Fimrite of Sports Illustrated.

By Fisk’s estimation, Tiant featured 20 different pitches as part of his complete repertoire. He threw the four standard pitches—fastball, curve, slider, and change-up—but with four variations on each pitch based on differing arm angles—over the top, three-quarters, and sidearm. And then, as Fisk proceeded to explain, there were six different speeds for both the Tiant curve ball and the Tiant change-up.

Tiant exhibited some decline in his game in 1977 and ‘78, but pitched well enough to draw free agent interest from the Red Sox’ principal rivals, the Yankees. Underestimating his popularity in the clubhouse, the Red Sox failed to make an aggressive offer. With George Steinbrenner and GM Cedric Tallis calling the shots, the Yankees signed Tiant to a two-year contract, with the bonus of a 10-year deal in which Tiant would serve as a scout. The willingness to give him the two-year pitching deal raised some eyebrows in baseball circles because of Tiant’s age. He was officially listed as 39, but rumored to be several years older.

“El Tiante” justified the deal in his first season with New York. While the Yankees suffered through an injury-ravaged, tragedy-wracked season (one that was marred by the death of Thurman Munson), Tiant delivered reasonably good return on his contract. He won 13 of 21 decisions, sported a 3.91 ERA in 195 innings, and emerged as the team’s No. 3 starter behind Ron Guidry and Tommy John.

The Yankees improved considerably in 1980, but Tiant’s pitching showed significant slippage. His ERA rose almost a run to 4.89, his won-loss record fell below .500, and he fell out of the postseason rotation. Tiant did not pitch at all in the League Championship Series, instead watching his team lose a trio of stunning games to the underdog Kansas City Royals. Forty years old and clearly tumbling downhill, Tiant found no interest from the Yankees. Settling for a minor league contract from the Pittsburgh Pirates, Tiant started the season with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, pitched a minor league-no-hitter, and eventually worked his way back to the big leagues with the Pittsburgh Pirates. From there, he put in time with the Mexican League, again clawed his way back to the majors, this time with the Angels, but then watched his major league career come to a close with the end of the 1982 season.

While many pitchers of his era relied on the intimidation that accompanied a blazing fastball or a crackling overhand curve, Tiant embraced the elements of slyness, trickery, and deception in bringing batters to their knees. And while other pitchers were more dominant, it was that melodramatic motion and grab-bag assortment of creative pitches that made Tiant the most entertaining moundsmen of the era.

Tiant, who passed away on Oct. 8, 2024, was a frequent visitor to Cooperstown. As the Hall of Famers paraded down Main Street in 2015, Tiant and another player from Cuba, Campy Campaneris, could be seen standing in one of the storefronts, intently watching the proceedings.

Almost as intently as we watched El Tiante create his artistry on the mound.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

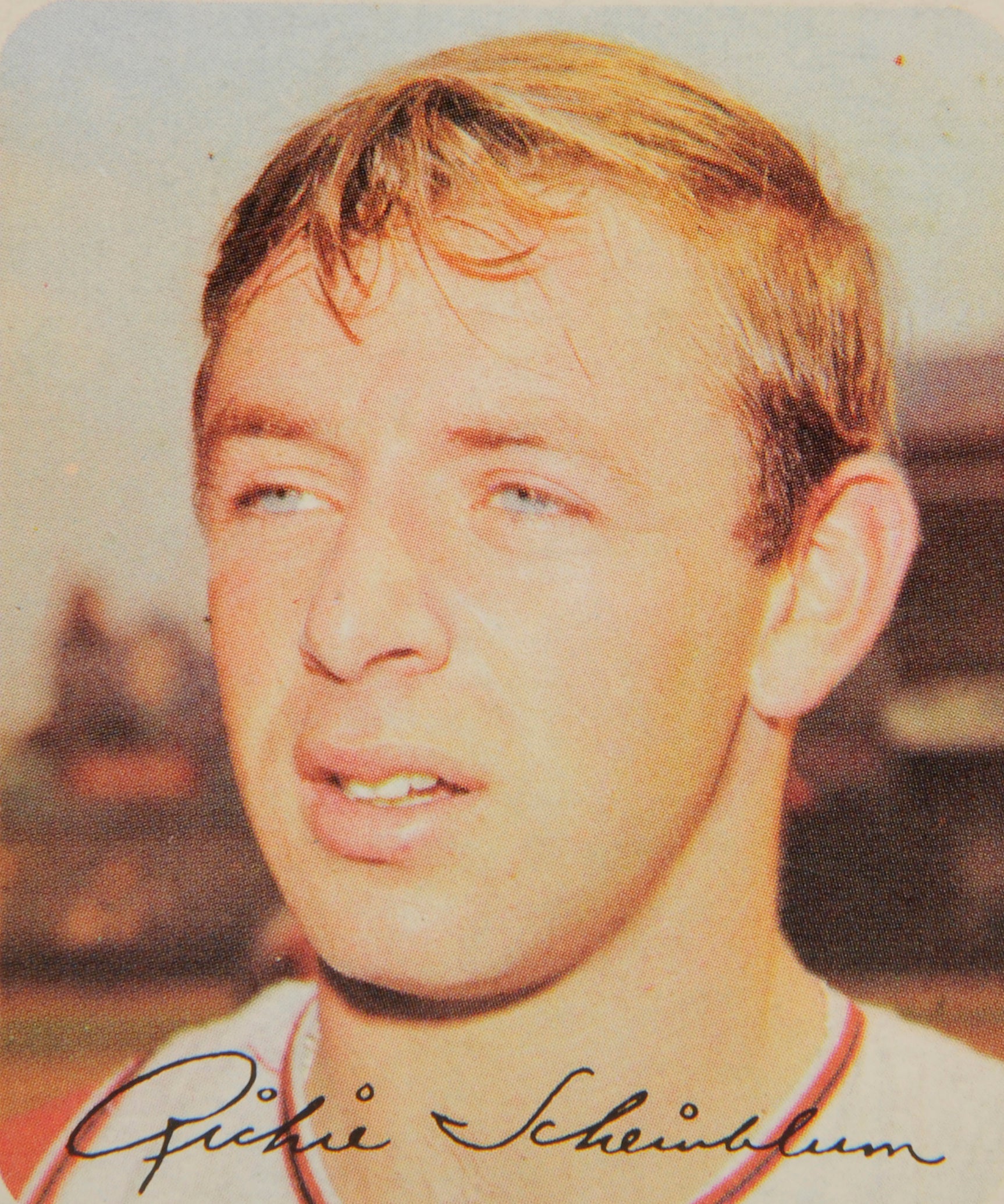

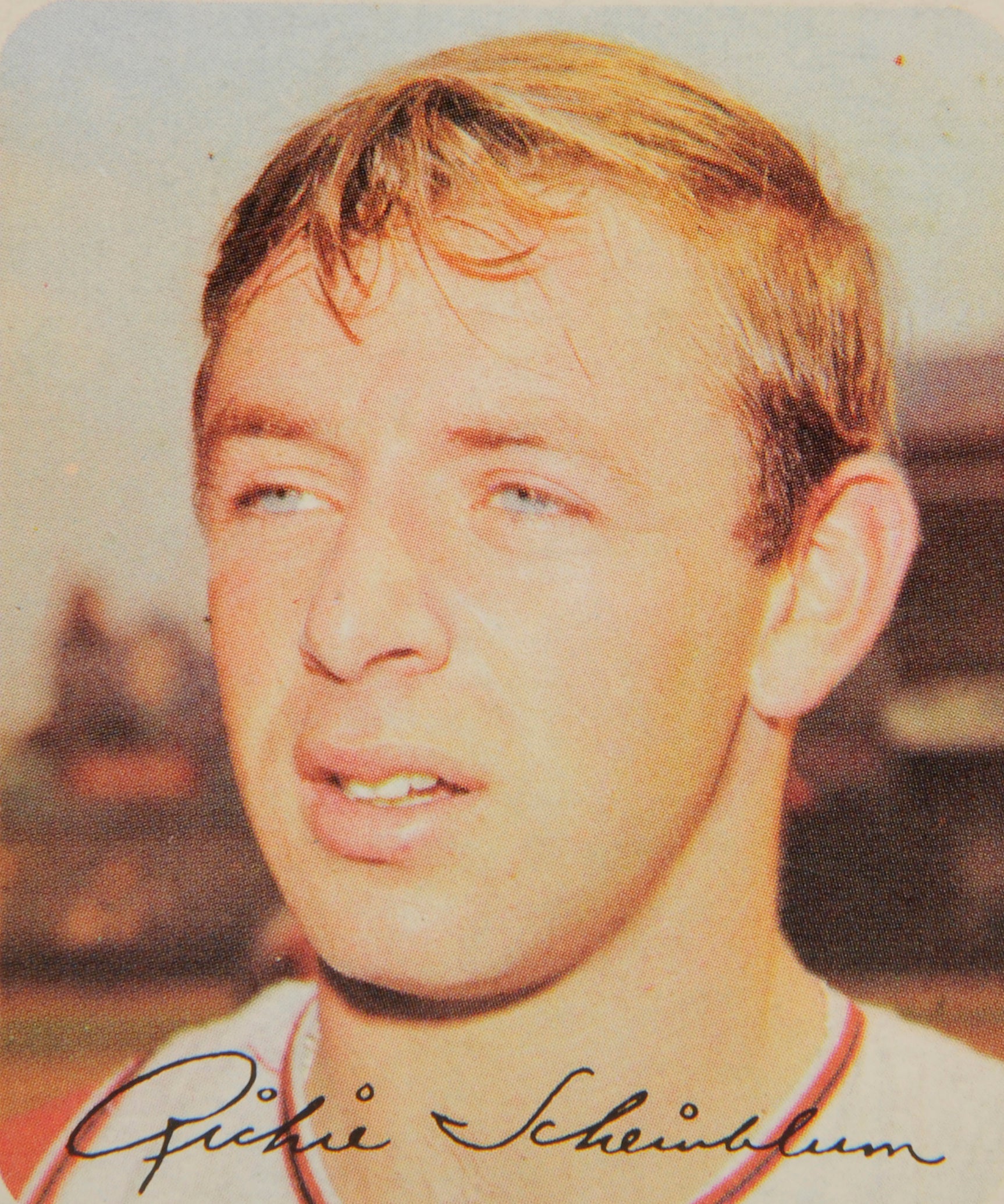

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

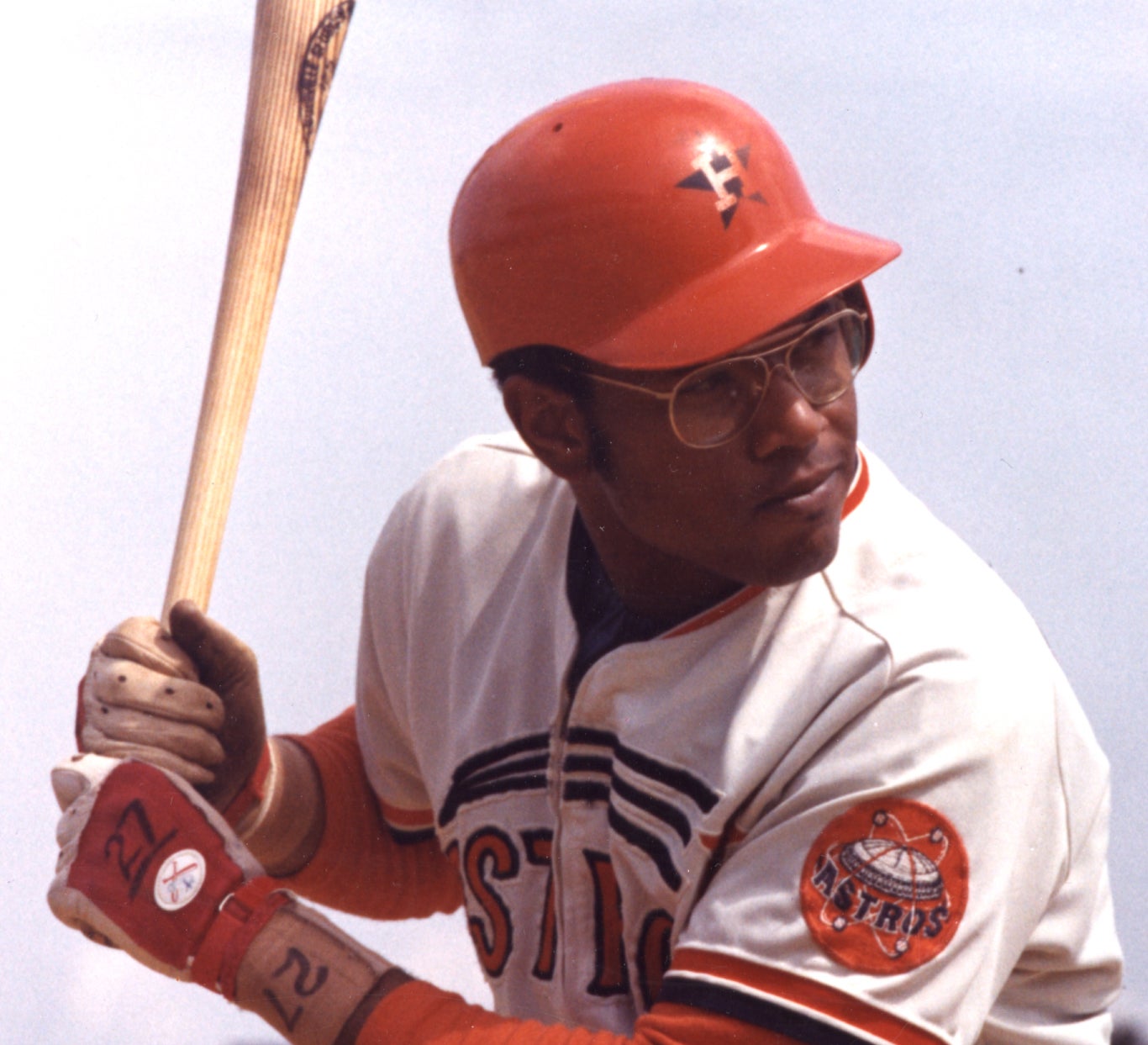

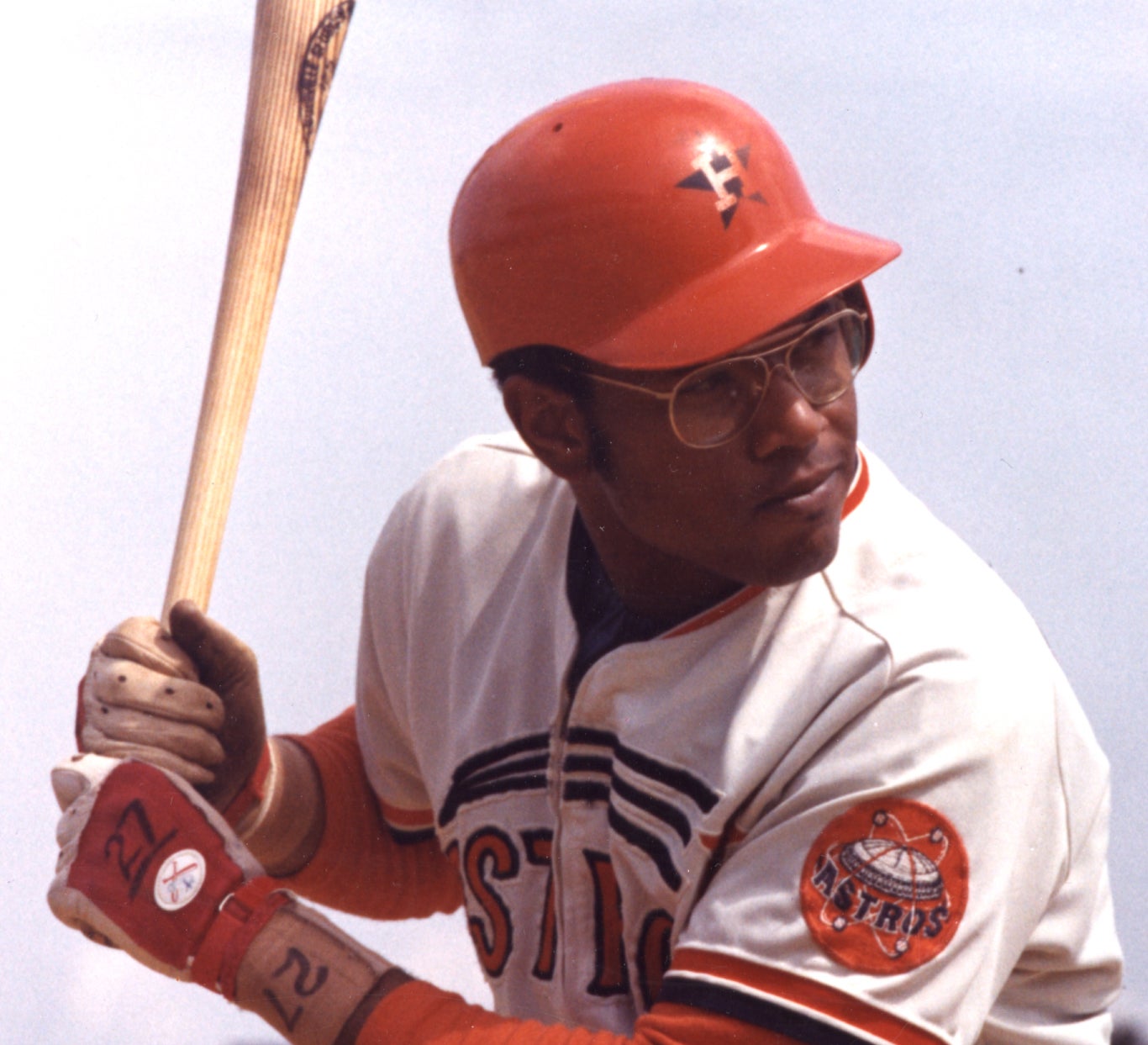

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Watson

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Watson

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

2007 Hall of Fame Game

Draft Records in Cooperstown

A Road to Equality

Goslin’s walk-off clinches Tigers’ first title

Hall of Fame Induction Weekend Visitors Urged to Utilize Special Parking Options

Character and Courage and Cooperstown

Pick a Pair: Hall of Fame Class of 2016 makes draft history

Main Street in Cooperstown becomes Boulevard of Baseball Dreams for Hall of Fame Weekend Saturday

01.01.2023