- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1989 Topps Bob Geren

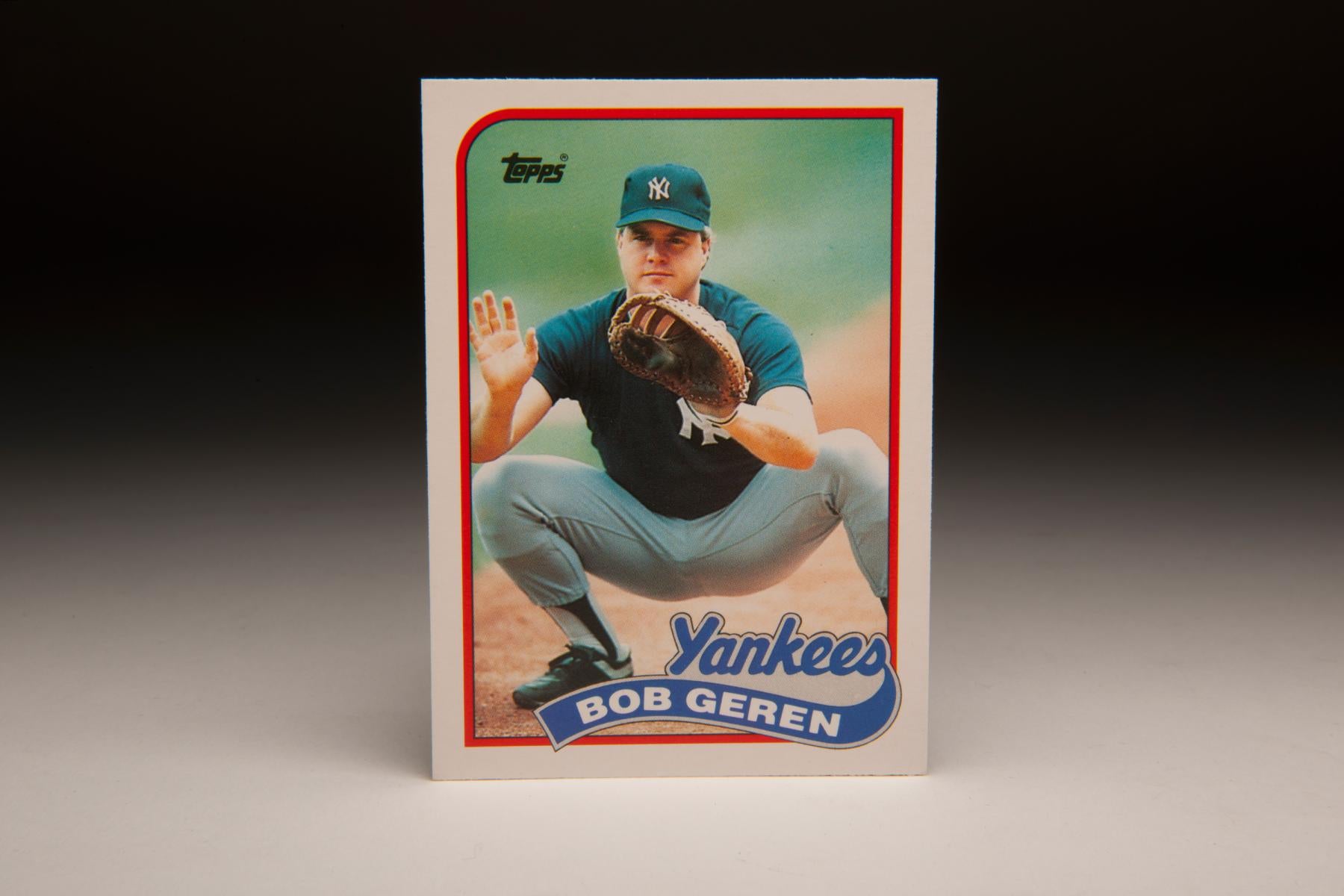

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Bob Geren

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

In discussing cases of mistaken identity on baseball cards, there is a tendency to introduce humor into the equation. There is something funny about the wrong name being attached to the wrong player, even if it might be a bit insulting to the player in question. We tend to ask ourselves somewhat comically, “How could a photographer from Topps mistake the California Angels’ batboy for Aurelio Rodriguez?” (1969 Topps) or “How exactly did Gary Pettis’ little brother sneak onto his sibling’s Topps card?” (1985 Topps).

In a sport where fun is supposed to supersede the serious, it’s understandable to have a chuckle over such unintended mistakes.

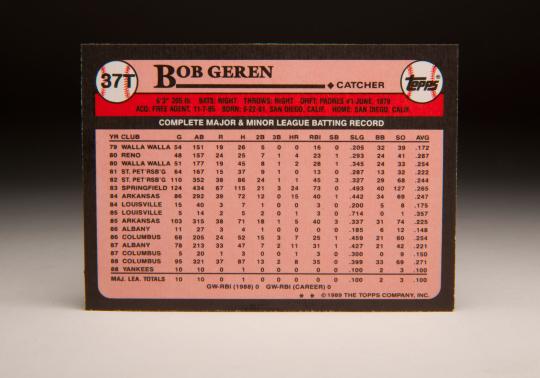

The story is a little bit different with the Topps 1989 Traded card of Bob Geren. Released in the middle of the 1989 season, the card is supposed to show the rookie catcher for the New York Yankees in a full crouch, ready to receive a warm-up pitch. Instead, we see a photograph of someone else; it is the late Mike Fennell, at the time a bullpen catcher in the Yankee organization. Fennell never played in the major leagues. Sadly, he died far too young, passing away in his early forties.

Unlike the Angels batboy who was mistaken for Rodriguez and in contrast to the younger Pettis, Fennell actually played professional baseball. The Yankees selected the upstate New York native out of Lemoyne College in the 10th round of the 1982 draft, assigning him to Oneonta in the NY-Penn League. As a rookie, he became a teammate of John Elway. A left-handed hitter with a good batting eye, Fennell showed some promise, compiling a .401 on-base percentage, which became more impressive in light of the NY-Penn League’s reputation as a pitcher’s league.

A combination catcher and first baseman, Fennell continued to show promise in his second season, this time with Greensboro of the full-season South Atlantic League. He again drew walks at a good pace, 91 for the season, and also blasted 12 home runs. As a left-handed hitter who could also catch, Fennell looked like a keeper.

Unfortunately, luck did not follow Fennell into his third season. Injuries curtailed his campaign, limiting him to only 54 games with Ft. Lauderdale of the Florida State League. He finished the season with only one home run and a .289 on-base percentage. He then underwent surgery on his throwing shoulder, which delayed the start of his season in 1985. When Fennell returned, he was not the same player. Assigned to Albany-Colonie of the Double-A Eastern League, Fennell batted only .175 in 16 games and then drew his unconditional release. A release at that level usually signals the end of a playing career - and that’s exactly what it did with Fennell.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Fennell’s playing days had ended, but his smarts and good attitude so impressed the Yankees that they hired him as a minor league coach before promoting him to the major league staff as bullpen catcher. He continued to hold that position in 1989, when Topps released the memorable card of Bob Geren.

So how did Fennell make his way onto Geren’s Topps card? It wasn’t Fennell’s idea; it was Geren’s. It happened during spring training. Wanting to play a practical joke on the photographer from Topps, Geren asked Fennell, who was working as the Yankees’ fulltime bullpen catcher, to “pinch-pose” for Geren. Fennell stepped in, the Topps’ photographer never realizing the difference. And thus a baseball error card was born.

From his stint as a bullpen catcher, Fennell found success as a high school baseball coach. In 1992, he was named the head coach at McQuaid Jesuit High School in Rochester, NY. Over his first six seasons with the program, McQuaid won nearly 75 percent of its games. Fennell eventually guided McQuaid to its first sectional title in 20 years. Even more importantly, Fennell became a popular man in Rochester, a father figure to many of his players.

A number of his players heard about Fennell’s appearance on a Topps card. “A lot of them are collectors, so they’ve become aware of it,” Fennell once told Scott Pitoniak, a respected writer for the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “They’ll look at the picture and joke, ‘Hey, coach, you didn’t have any gray hair back then.’ I tell them, ‘I know. You guys are responsible for this head of gray.’ ”

In reality, Fennell loved his players, who played hard and well for him. Their relationship seemed destined to last many more years, but heart-rending circumstances intervened. Only days before McQuaid’s championship game in 2001, Fennell found himself in a hospital bed. Though he had never smoked, he had been diagnosed with lung cancer the previous November. Fennell was now recovering from the latest surgery that had been deemed necessary since his initial diagnosis.

Fresh off another series of chemotherapy treatments, Fennell attended the ceremony in which the team was given its championship trophy. With his hair gone and his body weakened by the treatments, Fennell made his way onto the playing field. His wife asked him to use a walker, but Fennell tossed it aside, instead walking onto the field under his own power. The show of strength amazed those in attendance.

On May 15, 2002, Fennell succumbed to lung cancer. He was only 42, though he seemed to have the wisdom and grace of someone much older.

While Fennell was taken from us much too soon, the man who was supposed to be featured on this 1989 Topps card remains active in baseball. He has managed, coached, and played, compiling a nice career over the span of more than 35 years.

Bob Geren overcame major odds in making the major leagues in the first place. First drafted and signed in 1979, Geren toiled in the minor leagues for more than a decade, first with the San Diego Padres and then the St. Louis Cardinals. A look at the back of his Topps card reveals a litany of minor league stops along the way, including layovers in Walla Walla, Reno and Arkansas. At one point, he was considered a career minor leaguer, a good-field, no-hit catcher who appeared to have peaked with his promotion to Triple-A. But Geren made his way onto the Yankees’ roster for 10 games in 1988, before surprising everyone with his output in 1989. With the Yankees looking to rebuild with youth, they gave Geren a good look - and he prospered. Playing in 65 games, Geren hit nine home runs and batted .288 while giving the Yankees a strong presence behind the plate.

Geren’s handling of the catching responsibilities would remain a strength, but American League pitchers caught up to him in 1990 by throwing him a heavy diet of breaking balls and inducing him to chase pitches out of the strike zone. Over the next two seasons, he hit .213 and .219, respectively, with nominal power. The Yankees waived him after the 1991 season; he signed with the Cincinnati Reds, but they released him during Spring Training. After a brief stop with the Boston Red Sox and their minor league system, he reunited with the Padres, who called him up in midsummer. Unfortunately, Geren didn’t hit much with San Diego, became a free agent at season’s end, and then opted for retirement.

Geren’s intelligence and level-headed nature made him a managerial candidate. He went to work as a minor league skipper, putting in time with the Red Sox and Oakland A’s, before Oakland promoted him to the major league coaching staff in 2003. Four years later, the A’s made him their manager, but his teams would struggle, never playing even .500 ball in four seasons. Shortly after the A’s fired him, some of the Oakland players criticized him for his lack of communication.

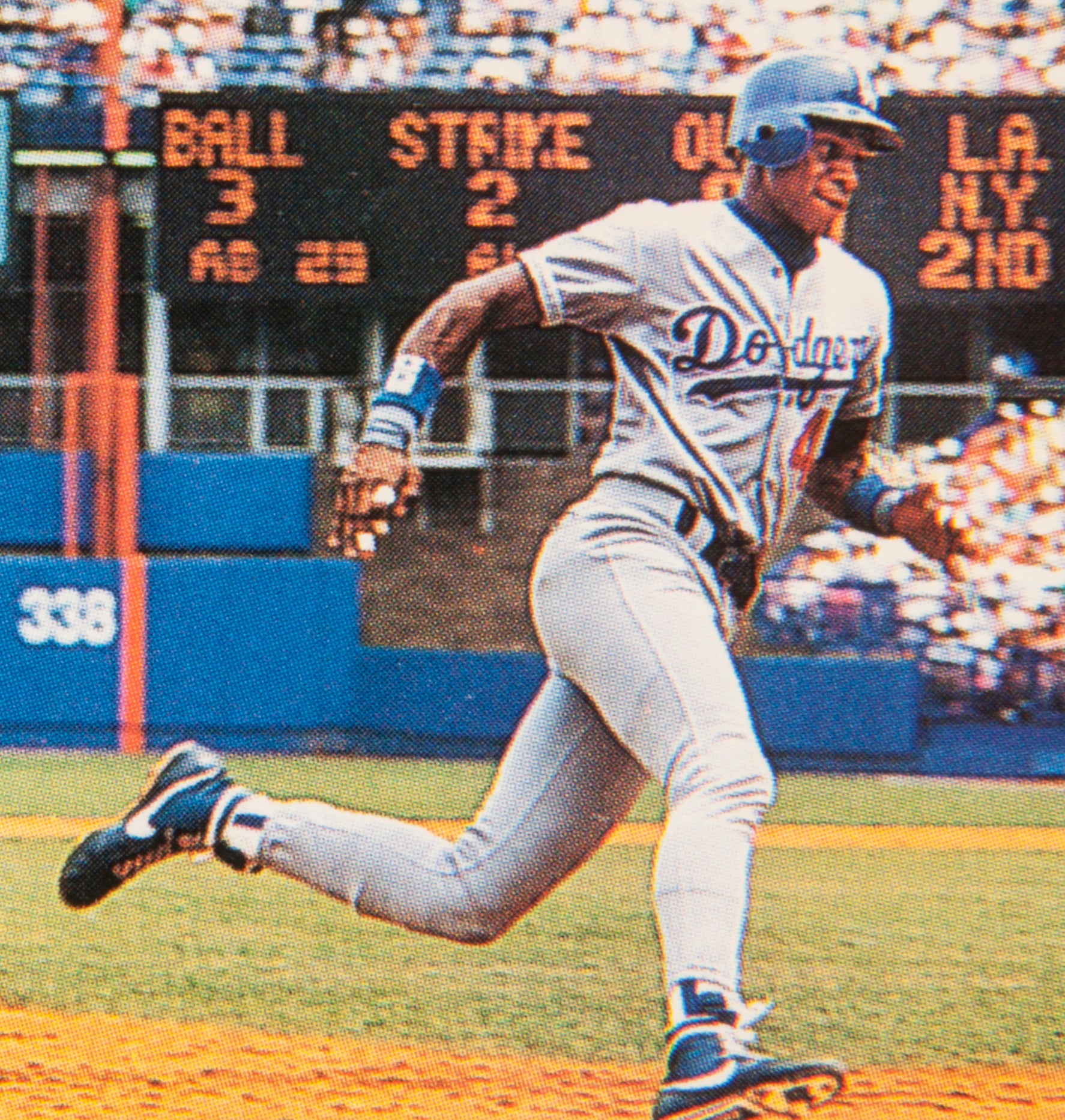

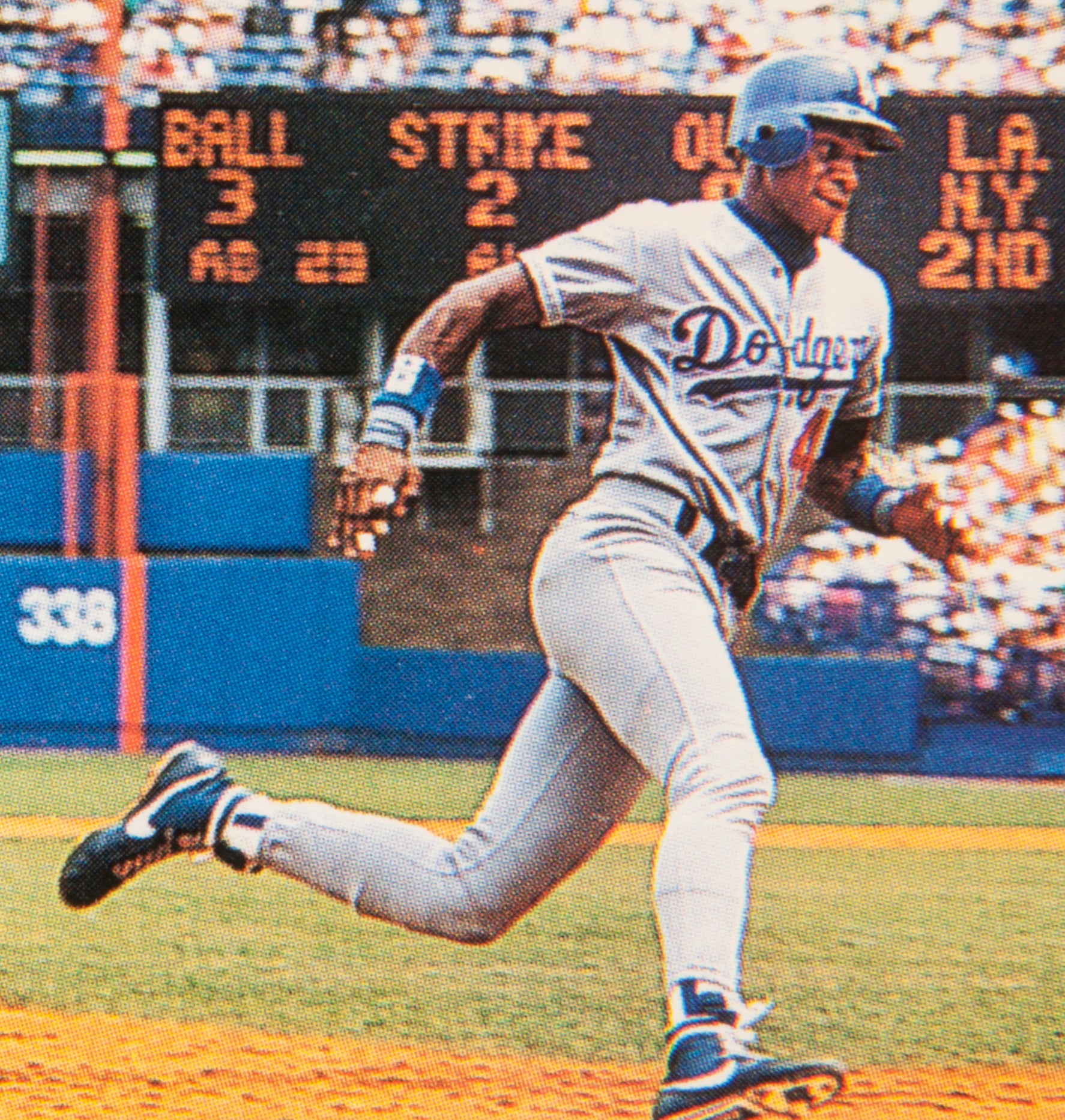

The New York Mets hired Geren as their bench coach in 2012; he remained in that position through last year’s World Series, before taking the same job with the Los Angeles Dodgers, a move that reflected his desire to be closer to family on the West Coast.

The criticism of miscommunication may or may not be valid. Yet, it is quite certain that back in the late 1980s, Geren relied on some intentional miscommunication in playing a prank on Topps. While that might have annoyed Topps at the time, it helped to create an intriguing case of mistaken identity on a baseball card. And without Geren’s mischief, we might not have learned the worthwhile story of a good guy and coach named Mike Fennell.

Special thanks to Scott Pitoniak for his help with this story and his remembrances of Mike Fennell.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

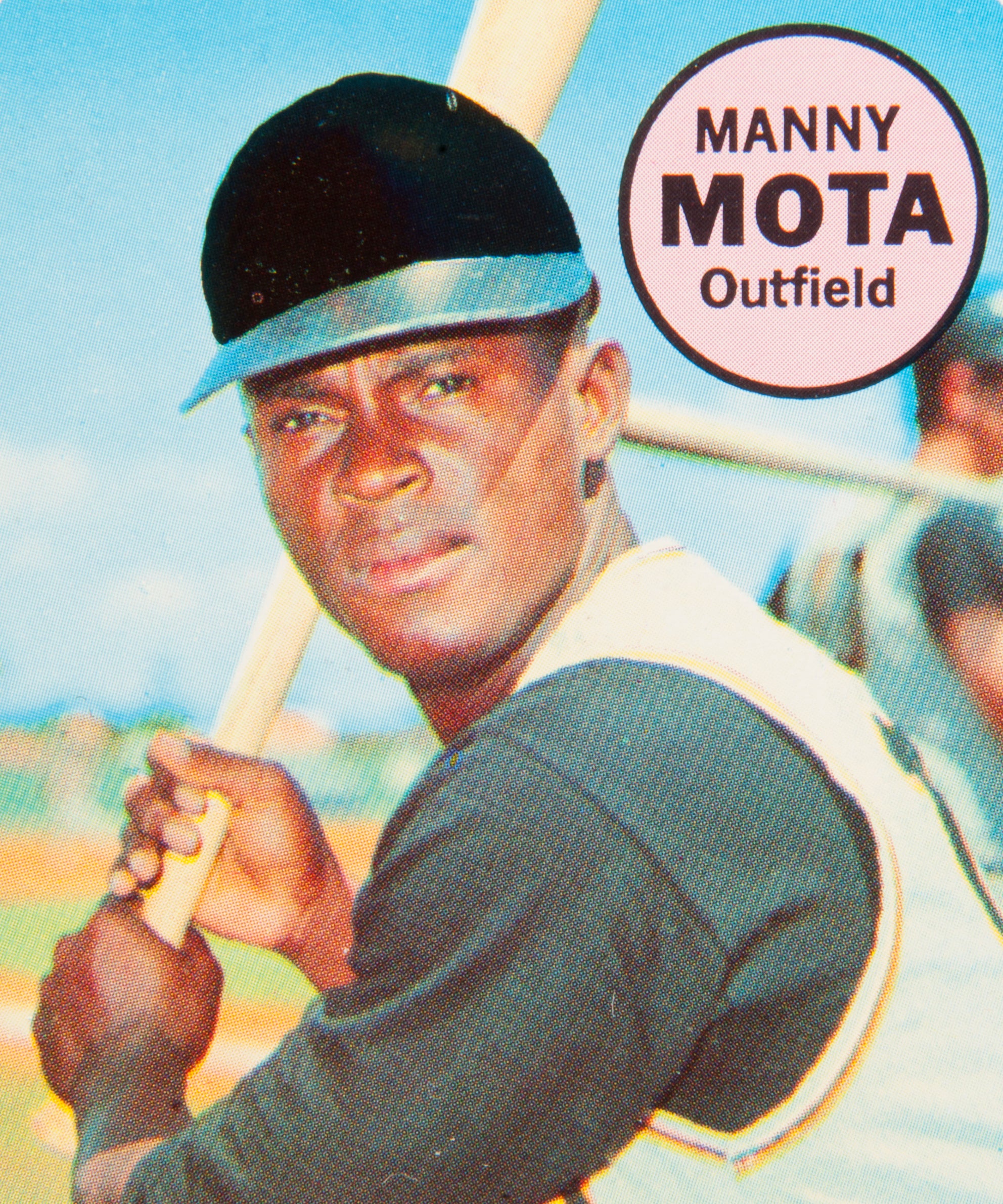

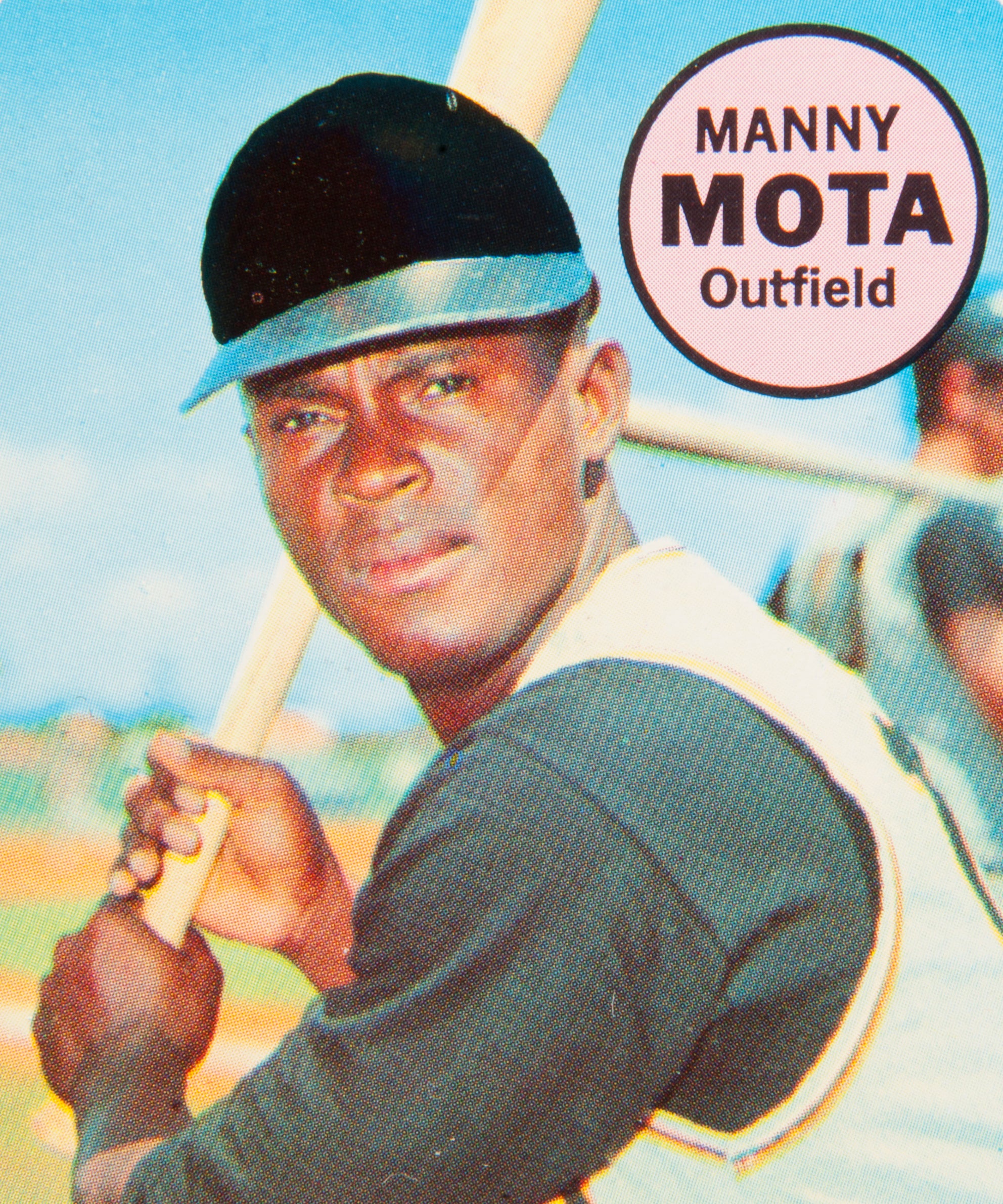

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Manny Mota

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

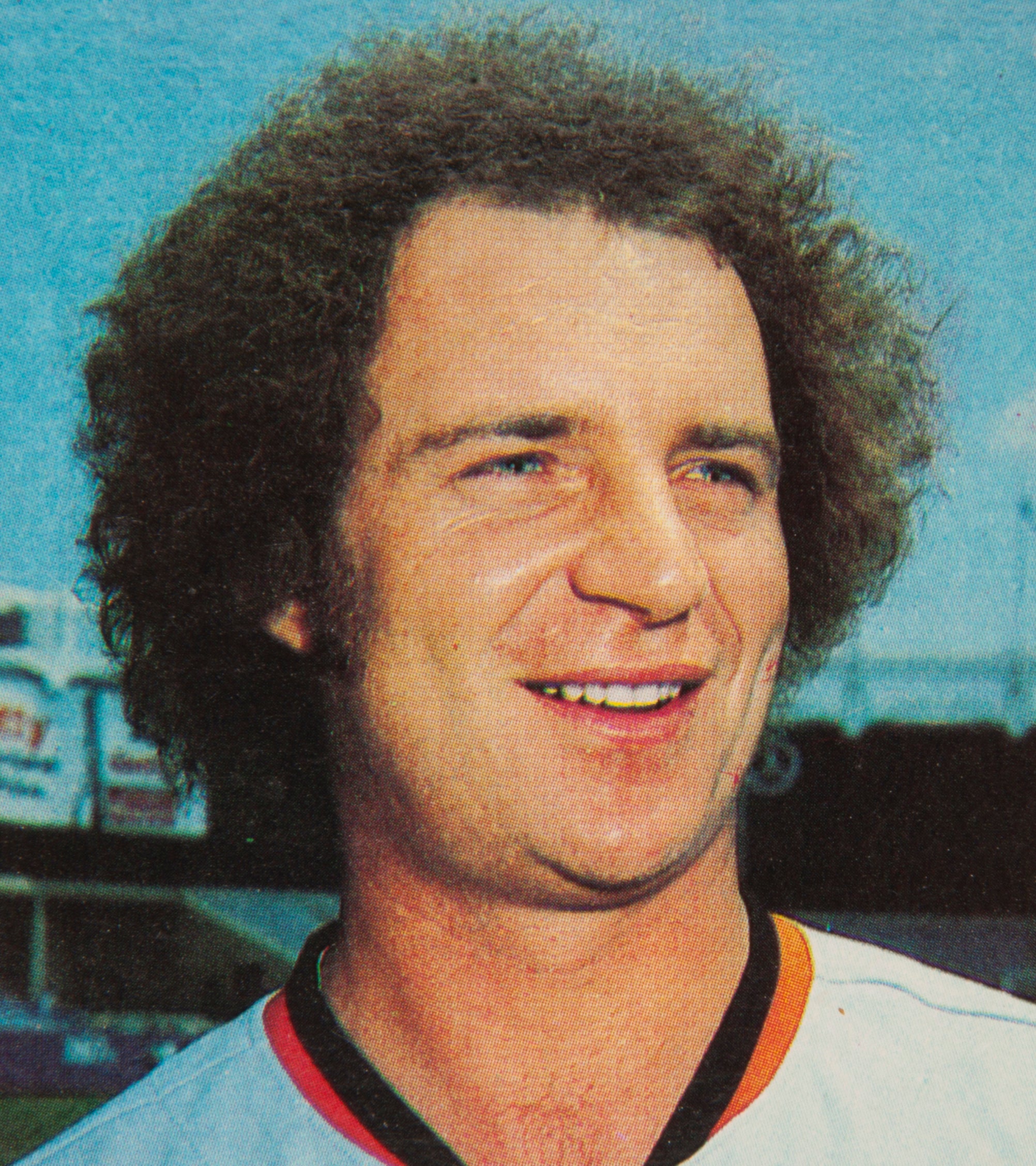

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1998 Topps Brian Jordan

A Glimpse of Moonlight

Hall to Honor Curt Flood’s Legacy, World War II Players during Awards Presentation at HOF Weekend

The Hall of Fame Remembers Jim Bunning

DICK ENBERG NAMED 2015 FORD C. FRICK AWARD WINNER FOR BROADCASTING EXCELLENCE

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

Hall of Fame Re-Launches Website at Baseballhall.org

01.01.2023