- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Lou Johnson

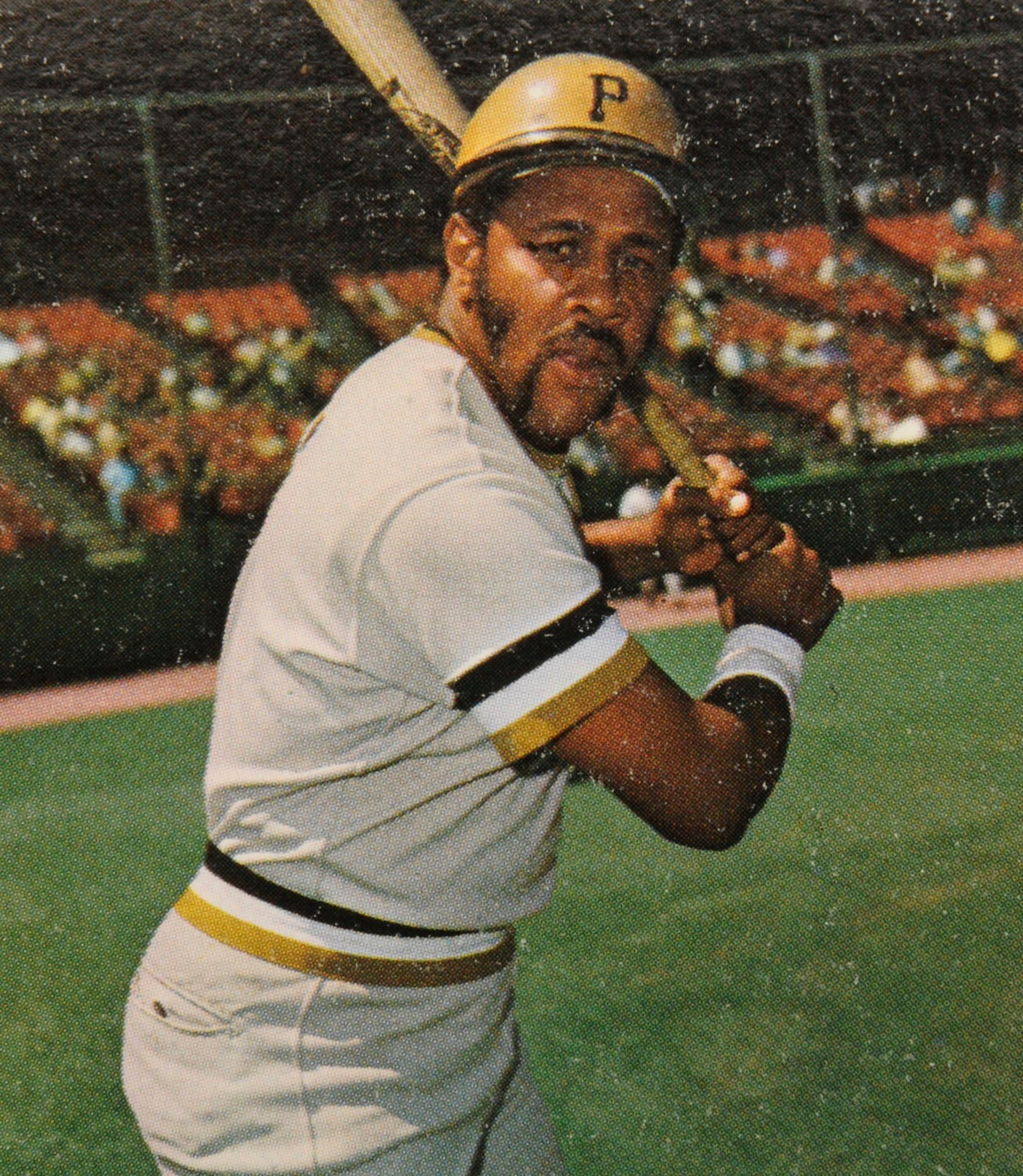

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Lou Johnson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The speckled border that Topps featured on its 1968 set of cards is one of the more creative examples of the company’s artwork. In contrast to the usual white or black borders, it gives the cards a dose of three-dimensionality. The photography in the set is generally well done, with plenty of good close-ups that show us what the ballplayers looked like in their 1960s heyday.

Among my favorites in the 1968 set is the card of Lou Johnson. I like cards that show players sweating, like Clay Carroll’s 1966 Topps card (where he appears to be almost drenched after a Spring Training workout) and the 1972 card of Houston Astros slugger Lee May. While not sweating as profusely as either Carroll or May, Johnson still shows some evidence of moisture on his face. It’s a good reminder that baseball can be hard work, whether it’s Spring Training calisthenics or the demands of a regular season game.

There’s something else that’s unusual about Johnson’s card. The movement of his mouth makes it look like he’s whistling. Or maybe he’s yelling to someone as his picture is being taken. Either way, it give us a different look from the standard baseball card. So many players look so expressionless, and so obviously silent, on their cards. To see a player whistling or talking (or perhaps even singing?) on his card, that gives us something unconventional.

One thing that this 1968 card does not provide is any evidence of the secret that Johnson was hiding at the time. He was a player who didn’t socialize with his teammates, a man who didn’t want other players to see what he was really like away from the ballpark.

To his teammates, Louis Brown Johnson was known as “Sweet Lou.” In fact, he is one of three “Sweet Lous” in the history of the major leagues. The best known is probably Lou Piniella, who found success as both a player and as a manager. Then there is Lou Whitaker, the fine second baseman for the Detroit Tigers and the longtime double play partner of Alan Trammell. The most obscure of the three, at least to most fans, would be Johnson, who spent much of the 1960s bouncing around the minor leagues before finally finding his niche with the Los Angeles Dodgers. He then closed out his career as a bit player with the Chicago Cubs, Cleveland Indians and California Angels. Though Johnson played only three seasons with the Dodgers, he managed to become one of the most popular players in the franchise’s long history.

In addition to the “Sweet Lou” moniker, Johnson had another nickname; he was sometimes called “Slick.” That might also be the word used to explain his long road to Los Angeles - slick and treacherous. As a young athlete growing up in Lexington, Ky., he had hoped to play basketball for the Kentucky Wildcats, but the Southeastern Conference did not recruit black athletes at the time. “My dream was to play basketball at the University of Kentucky, where my mother and father worked, but they wouldn’t take blacks,” Johnson told Ken Gurnick of MLB.com, “so I never was involved with the university, and that haunted me a long time.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Discouraged by the racial roadblock in basketball, Johnson turned to baseball. He signed with the New York Yankees in 1953 but lasted only one season in their minor league system before being released. Prior to 1954, the Yankees sent him to a minor league team in the Mountain States League in what Baseball-Reference describes as an “unknown transaction.” Before each of the next two seasons, Johnson again moved on in unknown transactions, first to the Pittsburgh Pirates and then to the Cubs. Johnson just might have set an unofficial record for being involved in the most “unknown transactions.”

Johnson also spent part of the 1955 season playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in the later incarnation of the Negro Leagues. By then, the Negro Leagues had passed their prime, but they still represented legitimate opportunities for African-American players hoping to extend their careers.

Johnson took special pride in playing for the Monarchs. “The highlight of my career was playing for the Kansas City Monarchs and being chosen to play in the East-West All-Star Game in front of people at Comiskey Park,” Johnson told Sports Collectors Digest. “The caliber of the organization was great. I learned to play baseball there.” Johnson’s teammates included the great Satchel Paige. He played under manager Buck O’Neil, who would later gain fame for his role on the 1994 Ken Burns documentary, Baseball.

O’Neil, who doubled as a scout for the Cubs, advised his bosses to sign both Johnson and slugger George Altman. On O’Neil’s recommendation, the Cubs purchased Johnson’s contract from the Monarchs. That move gave Johnson the break that he needed. The right-handed hitting outfielder would spent the next four seasons wending his way through the Cubs’ system, finally earning a promotion to Chicago in the spring of 1960. But he batted only .206 in 68 at-bats, a subpar performance that earned him a return ticket to the minor leagues. Playing at Triple-A Houston, Johnson posted solid numbers: a .289 batting average, 12 home runs, and 13 stolen bases.

By now, Johnson was 25 and had plenty of experience playing minor league ball. Simply put, he had nothing left to prove at Triple-A. The expansion Los Angeles Angels showed interest, sending some cash Chicago’s way for the speedy outfielder. He would spend most of 1961 at Triple-A before receiving a chance to move up to LA. He played in exactly one game for the Angels before being traded, this time to the Toronto Maple Leafs, an independent minor league team, in exchange for outfielder Leon Wagner.

Johnson spent the rest of 1961 at Toronto, again putting up good offensive numbers, before being sold to the Milwaukee Braves that fall. But the Braves sent him back to Triple-A, so he started the 1962 season at Toronto once again, before the Braves called him up in the middle of the summer.

The Braves made Johnson their leadoff man and center fielder. Eventually putting in time at all three outfield positions, Johnson did well for the Braves. He hit .282 and put up an OPS just a shade over .800. He also played well in the outfield, showing range and smoothness. That should have been good enough to keep him in Milwaukee in 1963, but all it did was result in a return trip to the minor leagues. The Braves hardly played him during the spring and then demoted him to Denver just before Opening Day. For some reason, Braves management considered Johnson a poor influence on the team’s young players.

Years later, Johnson would publicly reveal some of the reasons behind that reputation. “I had been drinking since I was 13,” Johnson told famed sportswriter Jerome Holtzman. “I was always very insecure.”

Essentially blackballed from Milwaukee, Johnson remained in the minors for the next three seasons, while being bounced from the Braves to the Detroit Tigers to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Johnson almost quit the game, as he talked about giving up baseball for the relative safety of selling cars. But he stuck with it and returned to active major league duty in 1965 with the Dodgers. Johnson actually started the season in Triple-A, but received a call-up in May when Tommy Davis suffered a severely fractured foot. Manager Walter Alston called on Johnson to replace Davis in left field, taking his place alongside Willie Davis and Ron Fairly in a talented Dodgers outfield.

Labeled the “hobo of the minors” by the Sporting News, Johnson filled in beautifully for Davis, a two-time batting champion. Johnson batted only .259, but he hit 12 home runs (which tied for the team lead), stole 15 bases, and played an excellent left field. He also scored the lone run of Sandy Koufax’ perfect game on Sept. 9. After drawing a walk, he stole second base, moved to third on a sacrifice and then came home on a throwing error by Chicago Cubs catcher Chris Krug. In so doing, Johnson became a footnote to Koufax’ day of perfection.

For the season, Johnson played an important role in the Dodgers winning the National League pennant. He also became a fan favorite. The Dodger faithful appreciated his hustle and his enthusiasm. They also loved the way that he clapped his hands in celebration during games, even if the conservative baseball establishment frowned upon such in exuberance in the 1960s. Dodgers beat writers and teammates also enjoyed talking to Johnson, whose intelligence, humor, and outgoing personality made his locker a necessary stop on postgame tours. Johnson comically referred to himself as “L.B.J.,” which were not only his initials but also gave him something in common with U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson.

A veteran of 13 minor league seasons, Johnson was the least known of the Dodgers’ starting eight heading into the World Series, but soon made a national name for himself. Batting in the middle of the Dodgers’ lineup, Johnson tormented the pitching staff of the Minnesota Twins. Johnson picked up eight hits in 27 at-bats, including a pair of home runs. The second blast proved to be the game-winner of Game 7, by far the most important hit of his career. Dodgers fans celebrated by chanting “All the way with L.B.J.!” Practically unknown at the beginning of the season, Johnson was now a conquering hero.

When Tommy Davis returned to the Dodgers’ lineup in late April of 1966, Johnson switched from left field to right field. The Dodgers also rewarded Johnson by batting him third in the lineup. Johnson responded with his best season, including a .272 batting average and 17 home runs. He was also hit by pitches a league-leading 14 times, which helped his on-base percentage. Once again, the Dodgers reached the World Series, but did not play nearly as well as in the 1965 classic, losing the championship to the Baltimore Orioles in four straight. Johnson played respectably, picking up four hits in 15 at-bats.

In May of 1967, Johnson suffered a broken ankle, which reduced him to playing in only 104 games for the season. But his on-base percentage and his OPS both rose, as he remained a productive part-time right fielder.

As the Dodgers prepared for 1968, they decided to make room for younger outfielders Willie Crawford and Len Gabrielson. Johnson became expendable, traded back to the Cubs (his first major league team) for young infielder Paul Popovich and a minor leaguer. Johnson claimed the Dodgers made the trade for “personal reasons,” which were likely attributable to his drinking problems.

The Cubs thought they had room for Johnson in right field, but a foul ball in a late Spring Training game hit him in the head, fracturing his skull. Johnson eventually returned to the lineup, but the injury had a lingering effect. With only one home run through his first 62 games, Johnson’s lack of power worried the Cubs. Johnson’s time with Chicago turned out miserable for other reasons. He spent many of his nights on Chicago’s version of “Skid Row,” hanging around with homeless men on the street. Lonely and out of sorts, Johnson felt that he could identify with people who had been dubbed “bums” by the rest of society.

Shortly after the June 15 trading deadline, the Cubs dealt him to the Cleveland Indians for fellow outfielder Willie Smith. After the trade, Johnson publicly ripped several of the Cubs, including manager Leo Durocher and catcher Randy Hundley. Johnson failed to hit much for the Indians, who dumped him the following spring, sending him to the California Angels for the versatile Chuck Hinton. Batting only .203 in 67 games, he drew his release at season’s end. At 34 years of age, the well-traveled playing days of Lou Johnson had come to an end.

Johnson took a job working in sales for a company specializing in selling security systems, but would eventually return to baseball. In 1978, the Dodgers hired Johnson as a minor league instructor. Less than one year later, they fired him. He was unable to perform his duties, because of an addiction to alcohol and cocaine.

By the 1970s, Johnson was in trouble. One of his low points came when he gave up his World Series ring as collateral to a drug dealer, receiving only $500 in return. “I was doing just about anything to raise money for the cocaine habit,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I was writing bad checks, using my wife’s pay, conning people.”

He tried to commit suicide - not once but twice. “I’d jump in my car and I’d rive 60, 70 miles an hour in a 25-mile zone,” Johnson told Jerome Holtzman. “Once, I took an overdose, a big overdose of pain killers. I was tired. I didn’t want to wake up.”

Thankfully, Johnson did wake up. He eventually sought help. In 1980, he placed a call to Don Newcombe, the former Brooklyn Dodgers great who had managed to defeat alcoholism and was now leading efforts to assist others. With help from Newcombe, Johnson checked into an Arizona clinic called The Meadows, where he began the difficult process of rehabilitation. To this day, Johnson credits Newcombe with saving his life.

After rehab, Johnson returned to the Dodgers as part of their community services staff. He became one of eight former Dodgers players to appear at community and civic events as an official representative of the organization. For the effusive, bubbly, and energetic Johnson, the job represented a perfect match for his talents.

More than 35 years later, Johnson remains employed in the Dodgers’ community relations department, working as the team’s liaison. Now 81 years old, he continues to make dozens of appearances for the Dodgers throughout Southern California each year. For those who say that happy endings can’t take place, Sweet Lou Johnson is living proof that those skeptics are dead wrong.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

Related Stories

Treasures from 2014 World Series Headed Home to Cooperstown

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Oliver

Chip off the Block

Baseball Writers’ Association of America 2017 Hall of Fame Ballot Announced

Main Street in Cooperstown becomes Boulevard of Baseball Dreams for Hall of Fame Weekend Saturday

BASE Race Returns to Cooperstown May 28

A’s shut down Big Red Machine in thrilling Game 7

01.01.2023

Hall of Fame Class of 2015 Plaques to Visit Selected Ballparks Following Induction

01.01.2023