- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

In 1981, Topps Chewing Gum faced real competition for the first time in years. That’s when Topps’ longstanding monopoly, which started in 1956, came to an end. Thanks to a successful lawsuit, two other card companies, Donruss and Fleer, were allowed to produce rival card sets in 1981. That put pressure on Topps to come up with a quality card in 1981, so as to stem the tide from two burgeoning companies.

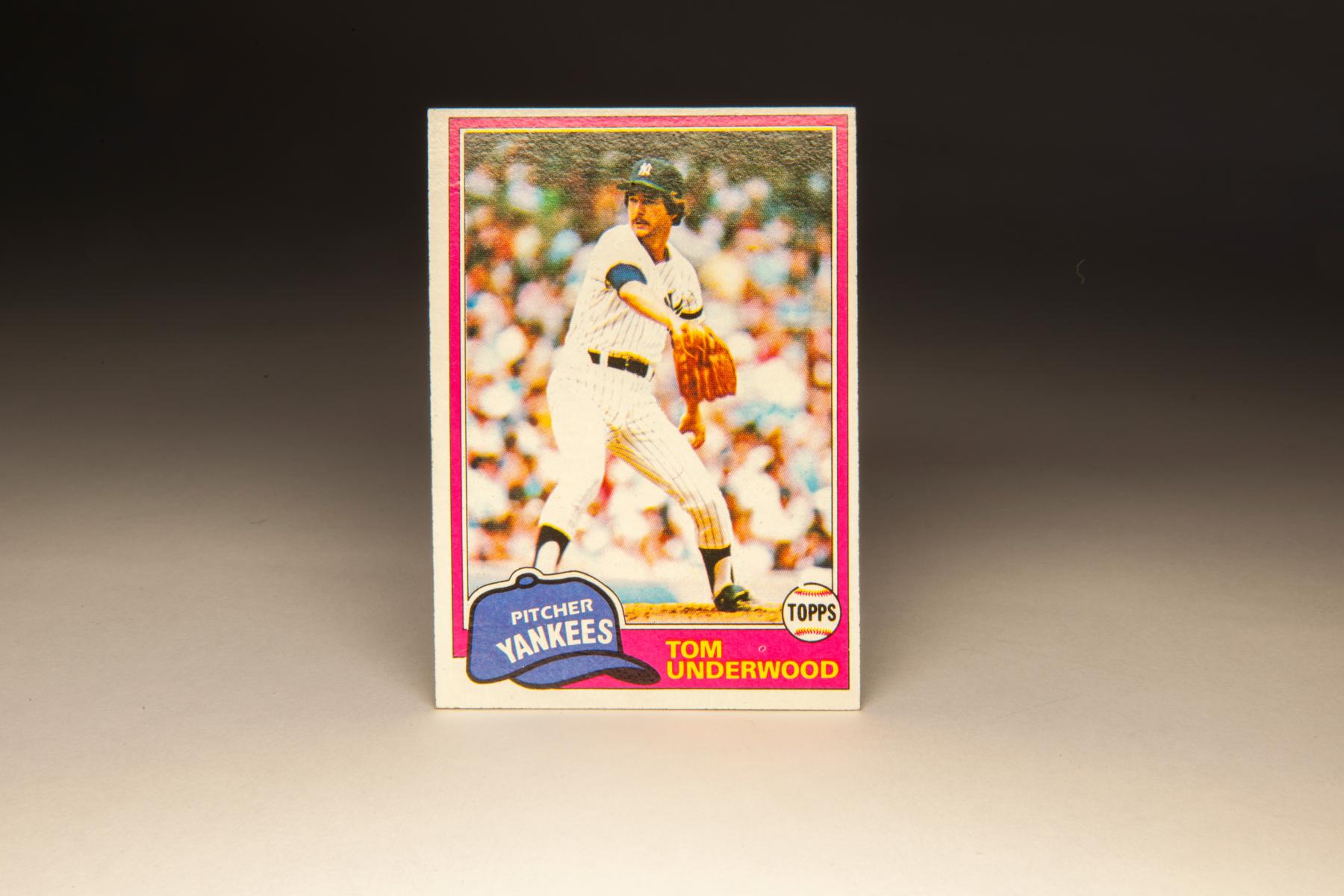

Well, Topps came through. The 1981 cards featured good photography, a nice mix of action shots and portraits, and a fun and colorful design. Each card had a colored frame around the picture, highlighted by a large, animated baseball cap in the lower left-hand corner of the card. The cap reflected the actual colors of the team, so the cap of the Oakland A’s had a green crown and a gold bill, while the San Diego Padres had their usual mix of brown and yellow. Instead of the team’s logo, the cap featured the name of the team, along with the player’s position. I’ve always liked the caps on these cards. They’re big and bright, and give the cards some three-dimensionality.

Among the cards produced in the 1981 set is this personal favorite. Tom Underwood is hardly a household name to baseball fans these days. He was never an ace, never a star, and his career ended rather abruptly. But if you’re in your forties or fifties, or close to it, then you likely have a distinct memory of Underwood. Whenever I hear his name, two words come immediately to mind: stylish left-hander. Underwood had one of those seamlessly smooth deliveries that I loved to imitate as a young boy growing up in Westchester County. Underwood also liked to work fast, which made him doubly fun to watch and would have made him an absolute joy in the all-too-deliberate pace of today’s game.

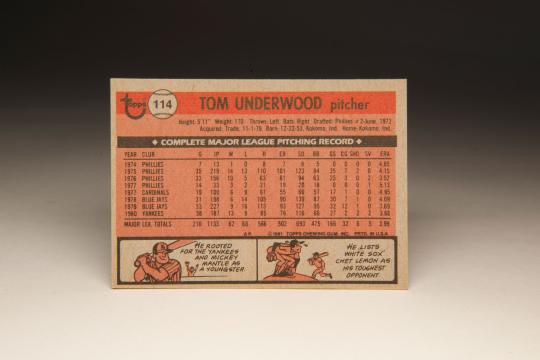

Part of Underwood’s delivery is captured on his 1981 Topps card. We see him in mid-pitching stride, very balanced as he toes the mound at Yankee Stadium. He’s also keeping his shoulder closed and has the ball tucked behind his back leg, obscuring it from the view of the hitter. These look like good mechanics to me. It’s just the way that I remember Underwood some 35 years later.

I also remember Underwood for being part of an unusual starting rotation. In 1980, the New York Yankees featured four left-handed starters. In addition to Underwood, they had staff ace Ron Guidry, followed by Tommy John and the underrated Rudy May. As I recall, that’s the last time that a major league team has ever had four full-time lefty starters. The New York media made a huge deal of it at the time, and not for favorable reasons. Some writers said the Yankees were too left-handed - a strange complaint for a team playing at Yankee Stadium - and kept pushing for the Yankees to trade one of the left-handers for a competent righty. At the time, I bought into the theory, but in retrospect, it seems somewhat silly. If you have four good pitchers like Guidry, John, May, and Underwood, who cares if they all happen to be left-handed? In today’s game, most teams would love to have two good lefties, not to mention a quartet of capable southpaws.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

At one time, it appeared Underwood would blossom into a star. Originally a highly touted prospect in the Philadelphia Phillies’ system, Underwood developed a reputation for baiting minor league umpires, both from on the field and in the dugout. One day, veteran pitcher Billy Wilson pulled Underwood aside and told him to stop picking fights with umpires. Underwood accepted the advice, changed his ways, and soon made the major leagues.

In 1975, Underwood won 14 games for the Phillies and made the Topps’ all-rookie team. That performance silenced some of his scouting critics, who complained that the 5-foot-11 Underwood was too short to be a starting pitcher. He pitched even more effectively in 1976, but then fell into the pattern of inconsistency that plagued his career. After a bad start to the 1977 season, the Phillies sent him to the St. Louis Cardinals as part of the package for speedy outfielder Bake McBride. He fared little better in St. Louis than he had in Philly, his ERA rising to 4.95. At season’s end, the Cardinals soon sent him packing to the expansion Toronto Blue Jays for a young Pete Vuckovich.

A recent expansion team, the Blue Jays didn’t have much pitching - or hitting. Underwood won only six games in 1978, but that was due mostly to a lack of support of his teammates. He led the team in strikeouts and gave the Jays indications that he could become a future star.

The next season, Underwood became involved in a bit of history when he faced his brother Pat, a right-handed pitcher for the Detroit Tigers, in a regular season game. Making his major league debut that day, Pat outdueled Tom, winning 1-0. Tom pitched well that season, again leading the Jays in strikeouts, but the lack of run support or a good defense frustrated him and resulted in him starting the season 1-10. “I’m not a 20-game loser,” Underwood told Murray Chass of the New York Times, “but I have a good chance of doing it. I don’t even know how I’ve lost 10 games.”

Underwood didn’t lose 20 that season - he stopped at 16 - but he clearly wanted a change of scenery. In turn, his occasional wildness frustrated the Blue Jays’ brass. After the season, the Jays decided it was best to part company, sending Underwood and young catcher Rick Cerone to the New York Yankees for veteran first baseman Chris Chambliss and two prospects, Damaso Garcia and Paul Mirabella.

While Cerone was the headline player in the deal from the Yankees’ standpoint, it didn’t take long for Underwood to impress New York fans with his fast pitching pace, his silky delivery, and his deceptively live fastball, which seemed to sneak up on hitters. He also had an overpowering curveball; on days that he could throw it for strikes, he became nearly unhittable. Emerging as a highly effective No. 4 starter behind Guidry, John, and May, Underwood won 13 games for manager Dick Howser and the 1980 Yankees.

I thought that kind of performance would be a springboard to greater success - the kind of success the Phillies had once foreseen - but Underwood started the 1981 season flatly. With a young Dave Righetti now ready to join the rotation, the Yankees decided to make a move. Trading Underwood at the valley of his value, the Yankees sent him to the Oakland A’s, including him with Jim Spencer in a package for underachieving first baseman Dave “The Rave” Revering.

After pitching as a swingman during the second half of the 1981 season, Underwood put together his most effective season in 1982. Again splitting his time between the bullpen and the rotation, Underwood forged a career best ERA of 3.29, won 10 games, and saved seven others. He became a favorite of manager Billy Martin, who liked Underwood’s versatility and willingness to pitch in any role.

Underwood’s performance slipped in 1983, which happened to coincide with the end of his contract. Although still only 29, the talented lefty drew little interest on the free agent market. He ended up signing a one-year contract with the Baltimore Orioles. But his manager, Joe Altobelli, refused to use him in anything but blowout games. At the end of one lackluster season in the Baltimore bullpen, an unhappy Underwood drew his release. And then nothing. Underwood, all of thirty years old, saw his major league career come to an end.

The Yankees, who were now managed by Martin, agreed to give Underwood a contract for 1985, but only under a minor league deal. They assigned him to Double-A Albany. By now, Underwood had put on too much weight and had lost something off his fastball. He struggled in both Double-A and Triple-A ball, failing to convince the Yankees that he had anything left. After the season, the Yankees released the veteran left-hander.

I’m not sure why Underwood’s career went south so quickly. In retrospect, it’s shocking that a left-hander with his talent did not pitch past his 30th birthday, not when we see some lefties stick around till their early forties simply because they happen to throw the ball with their left arm.

His career over so suddenly, Underwood left baseball completely to become a financial adviser with Well Fargo. One of his two children, J.D. Underwood, took up baseball and is now a prospect in the farm system of the Los Angeles Dodgers. J.D. is a pitcher, just like his father, but throws right-handed instead of left.

J.D. might make the major leagues one day, but sadly, his father will not see it. Much like his pitching career, Tom Underwood’s life ended at a young age. Underwood died in 2010 at 56, the victim of an 18-month struggle with pancreatic cancer. J.D. sat by his bedside the night that he died. Tom told his son not to cry, assuring him that he was going to beat the disease. Tom remained positive until the end, but the cancer proved too strong.

Like too many of his baseball brethren from the 1970s, Underwood left us way too soon. Underwood died the same year as a number of other significant players from that era, including Jim Bibby, Mike Cuellar, Willie Davis, Ed Kirkpatrick, Curt Motton, Wayne Twitchell and Hall of Famer Ron Santo.

Underwood did not have the career of a Bibby, a Cuellar, a Davis, or a Santo but he did succeed in making an impression on this fan, just like those players did. His final statistics will never do him justice. Far more importantly, he left me with some awfully good memories, memories that exceed the numbers, and for that I am grateful.

In the end, I guess that’s all we can ask from our ballplayers.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

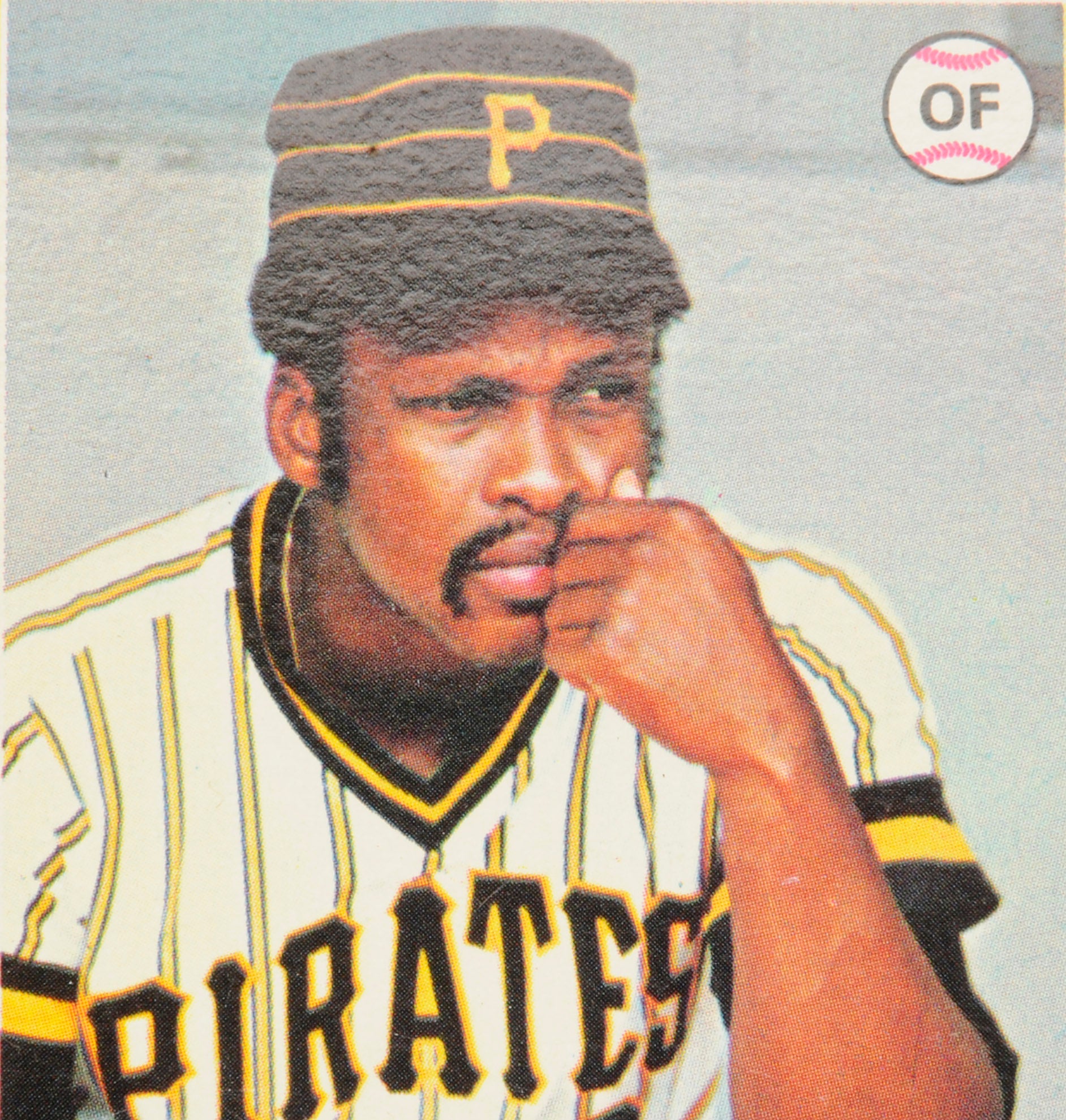

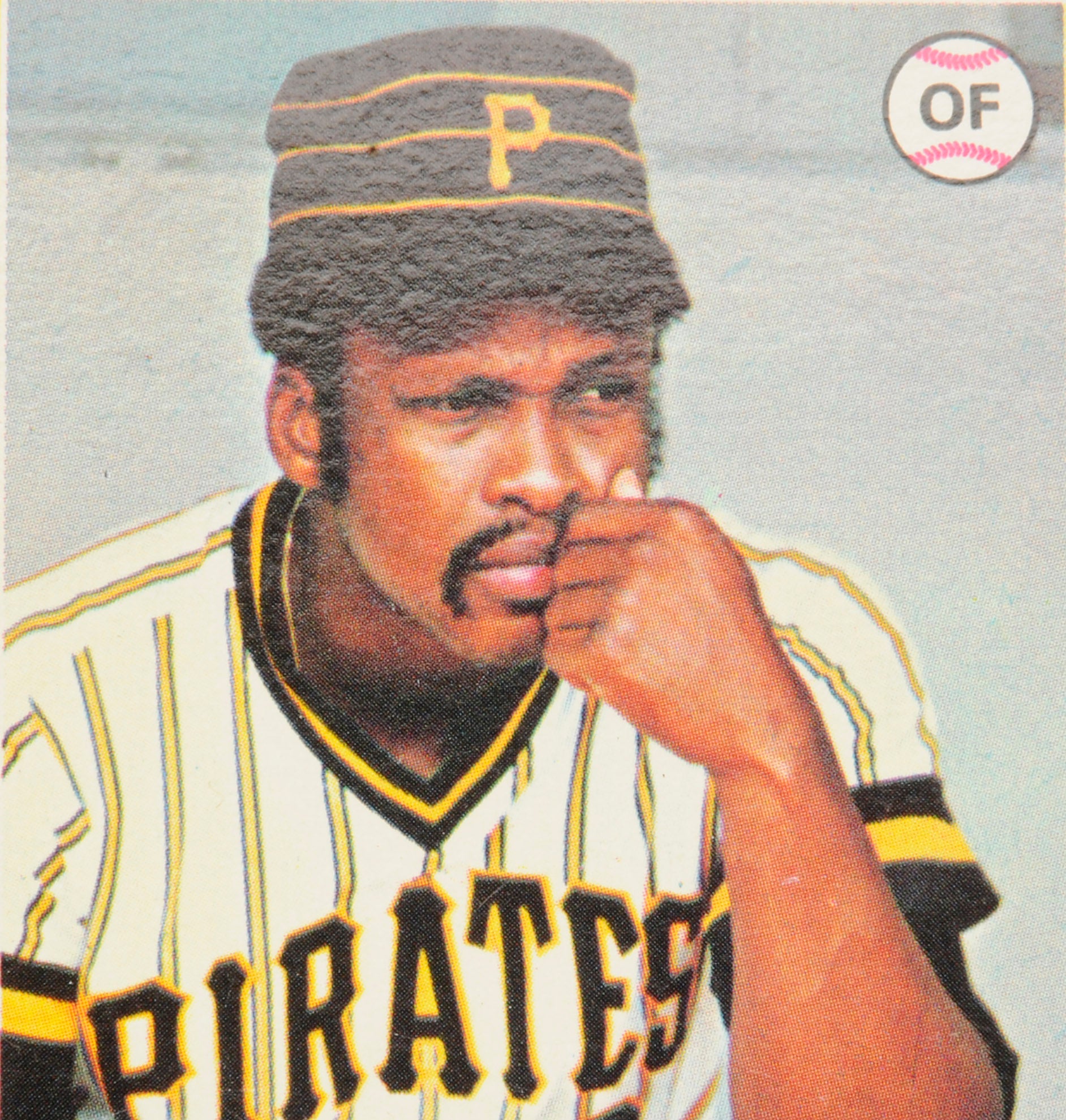

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Oliver

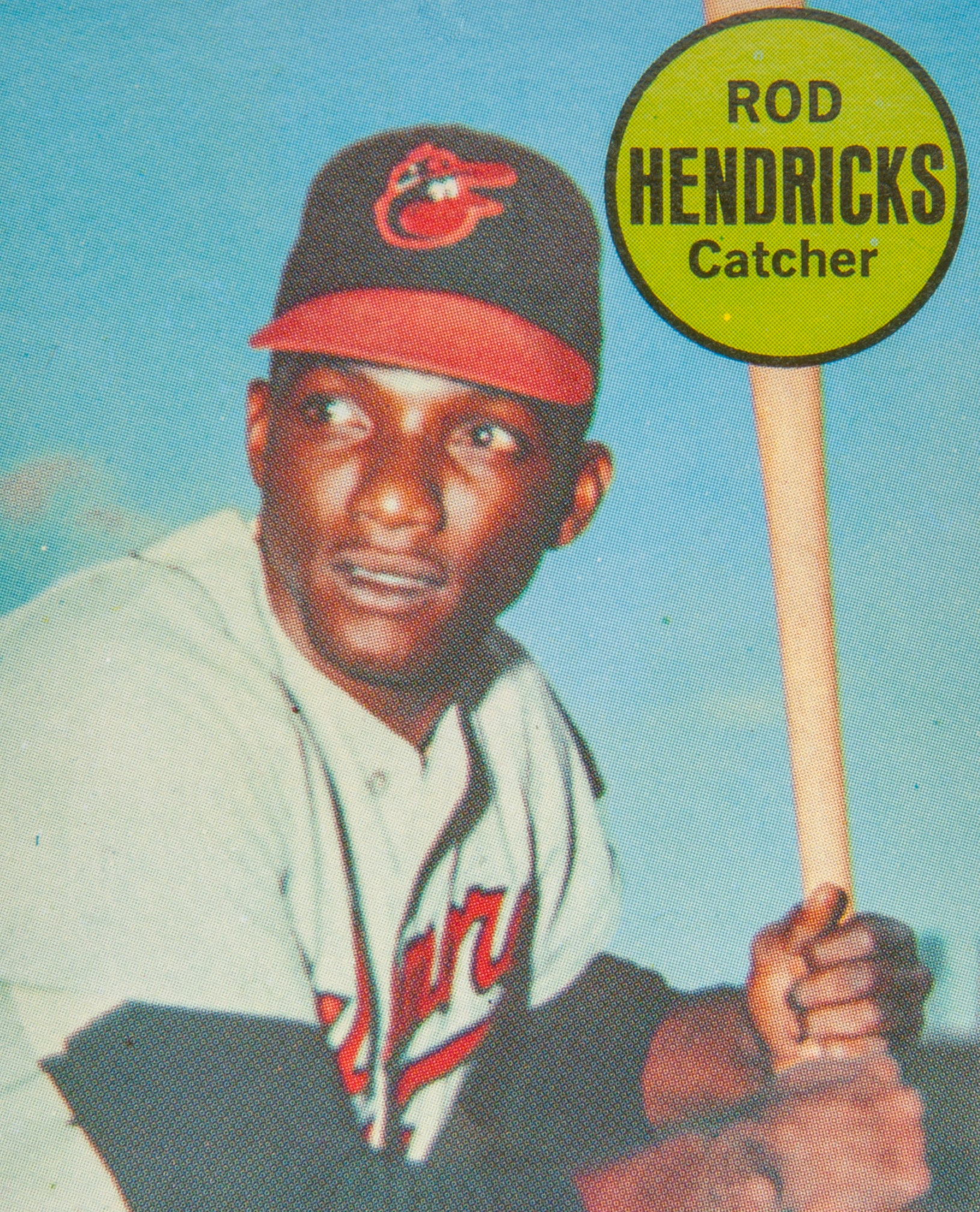

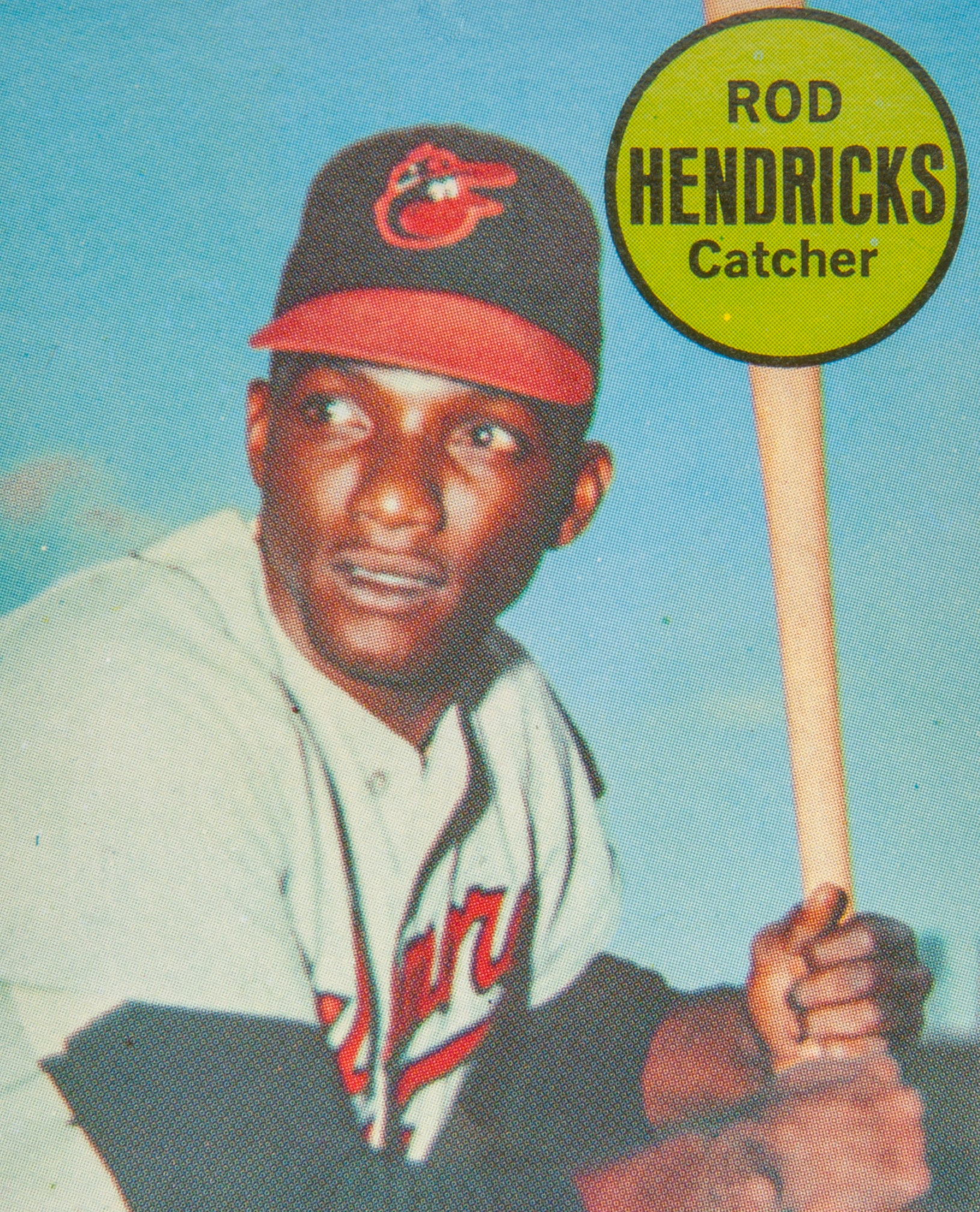

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

#CardCorner: T-Dog's Zombie Night First Pitch

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Oliver

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

#CardCorner: T-Dog's Zombie Night First Pitch

Related Stories

Master Entertainers

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

Rachel Robinson Named Buck O’Neil Award Winner

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

1968 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

1953 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

Yankees Slugger Alfonso Soriano Headed to Cooperstown for Hall of Fame Classic, May 23

01.01.2023

Ten Named To Golden Era Ballot for Baseball Hall of Fame Election

01.01.2023