- Home

- Our Stories

- Rube Foster’s writing predicted future of Black baseball

Rube Foster’s writing predicted future of Black baseball

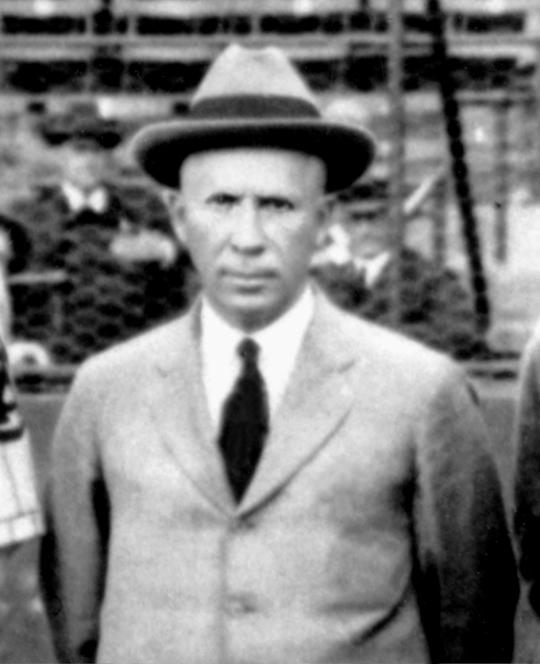

Rube Foster was called both an imposing pitcher and a visionary trailblazer. Both of these unique traits eventually landed him in Cooperstown as a Hall of Famer.

In 2020, Major League Baseball commemorated the 100th anniversary of the 1920 founding of the Negro Leagues. The centennial celebration – which included all MLB players, managers, coaches and umpires wearing a symbolic Negro Leagues 100th anniversary logo patch during games – can be traced back to the groundbreaking work of Foster.

In 1920, the United States saw women win the right to vote and prohibition enacted. But in a small corner of the Midwest, an event – almost a footnote at the time – took place that would in both the short- and long-term change the face of the National Pastime.

At a meeting with the owners of the top independent Black baseball teams at the Paseo YMCC at Eighth and Vine in Kansas City, Mo, on Feb. 13, 1920, the Negro National League, the first successful baseball league featuring black players, was founded. Leading the way was Andrew “Rube” Foster, who was considered Black baseball’s best pitcher before serving as owner and manager of the Chicago American Giants.

Foster headed north from his native Texas in 1902 to play for the Chicago Union Giants and soon became a star pitcher. Even though statistical data remains sketchy from those early days, Foster had to be an intimidating sight on the mound, standing 6-foot tall and weighing 200 pounds.

“Do not worry,” was Foster’s advice when faced with a difficult situation. “Try to appear jolly and unconcerned. I have smiled often with the bases full with two strikes and three balls on the batter. This seems to unnerve (the hitter).”

Foster went on to become the player-manager for the Chicago Leland Giants and soon “won a reputation as a managerial genius equal to his friend, John McGraw,” historian Jules Tygiel wrote in Past Time: Baseball as History.

Among those attending the 1920 meeting and ultimately – for a $500 fee that would bind them to the league and constitution – becoming initial members of this new enterprise were the baseball magnates of the top Midwestern teams: Foster, Tenny Blunt (Detroit Stars), Lorenzo Cobb (St. Louis Giants), John Matthews (Dayton Macros), Joe Green (Chicago Giants), C.I. Taylor (Indianapolis ABCs) and J.L. Wilkinson (Kansas City Monarchs). The Cuban Stars’ owner was unable to attend but sent along his approval of the league.

With organized baseball still segregated, the mid-February meeting was an attempt by Foster, who would be elected as the NNL’s first president, to bring stability to Black baseball for the first time.

A number of unsuccessful attempts had been made in the past, but this time, after a lengthy discussion, the other owners agreed to Foster’s proposal. While Black professional baseball had been part of baseball’s landscape for years, this new venture would do away with scheduling difficulties and bring a sense of financial security to both the owners and players.

Foster, considered a shrewd and successful leader, had been advocating for a black baseball league for some time. He penned a baseball column exclusively for the Chicago Defender – one of the leading Black newspapers in the country at the time – entitled “Pitfalls of Baseball” that ran from late 1919 to early 1920. In these pieces Foster, in his own words, lays the groundwork for what would soon become the NNL – with himself as the leader.

“Baseball as it exists at present among our people needs a very strong leader, and this leader to be successful must have able lieutenants, all of whom have the confidence of the public,” Foster wrote in the Dec. 13, 1919, issue of the Defender. “Only in this way can we be assured of success. Experimenting with the game from every angle, I am more convinced than ever that something firm must be done, and done quickly.

“Present-day promoters are blind to many facts. They do not realize that to have the best ball club in the world and no one able to compete with it will lose more money on the season than those that are evenly matched. The majority do not know a ballplayer when they see one. They have paid big prices for many lemons, thinking that if the man was a success with Foster we will work wonders with him. They forget that I have been a player whose intellect and brains of the game have drawn more comment from leading baseball critics than all the colored players combined, and that I am a student of the game. They do not know, as I do, that there are not five players nor three owners among the clubs who know the playing rules.”

By the Dec. 27, 1919, issue of the Defender, Foster was writing that he wanted to set up a meeting among the owners of the top black ball clubs to work on a mutual agreement they could all abide by.

“It is not a proposition to exchange players,” Foster wrote. “Each club will be allowed to retain their players, but cement a partnership in working for the organized good for baseball. Conducted on the same identical plan as both big leagues and all minor leagues, even the semipro leagues. The outcome would be the East would be the same National League, the West as American League; the winner of the majority of games in the East to meet the western winners in a real world’s championship. This will pave the way for such champion team eventually to play the winner among whites. This is more than possible. Only in uniform strength is there permanent success. I invite all owners to write for information on this proposition. It is open to all.”

But Foster’s column of Jan. 10, 1920, painted a dire outlook for any kind of working agreement among the various owners moving forward. Ultimately, however, by the next month, his dream was realized.

“In one of my previous articles I asked that the owners of clubs write for the plan of an organization or working agreement between the various clubs,” Foster wrote. “In this plan we were to have a regular western circuit, composed of Chicago, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Detroit, St. Louis, Kansas City, the eastern circuit to be composed of Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York, both to be two separate organizations, the same as National and American leagues, the winner of each circuit to meet in a world’s championship series. This would have been the salvation of baseball. But to date I have received but one letter that would be interesting; that letter came from Washington.

“There is something the people want, that their patronage demands, something that would make them appreciate their children entering a profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession, and that thing can be done only as the 128 leagues operated by the whites, that have measured their efforts with permanent success, so much so that a graduate from Yale, Princeton and many large medical schools and colleges of law have laid aside their college professions to become ballplayers, merely because it paid them better to do so. We can do the same thing, but only in patterning after the system of success used by them.”

It was no coincidence that the NNL’s founding came at the same time as the Great Migration, when a half million Blacks left the rural south to live and work in northern cities. The new league would have an eager audience looking for a source of inexpensive entertainment long day of hard labor.

NNL umpire Billy Donaldson had glowing remarks about both Foster and the new league.

“He (Foster) is not only a strategist but a baseball pioneer and organizer. He is the father and organizer of the Negro National League, the first organization of its kind where boys of our Race could get employment as players and make a place for themselves in the baseball world,” Donaldson said. “The forming of the Negro National League started the ball rolling and now we have several leagues in the country where it is possible for our boys to make a decent living at playing ball.

“Race fans should be very thankful for a league and do their very best in turning out to the games in full force, showing their appreciation toward Mr. Foster and his league. They will find the same caliber of high class play that is dished up by the white major leagues.”

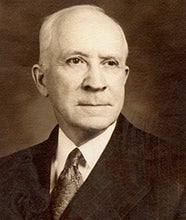

Judge W.C. Hueston, president of the NNL in the late 1920s, stated that it was his belief that the league was the greatest leveler of prejudice. “It was also the best propaganda possible in advance of the theory that our group could do anything as well as whites.”

Judging by the number of NNL players who would eventually be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, such as Rube Foster’s half-brother Bill Foster, Turkey Stearnes, Pete Hill, Oscar Charleston, Biz Mackey, Ben Taylor, Cool Papa Bell, Ray Brown, Andy Cooper, Pop Lloyd, Jose Méndez, Joe Rogan, Mule Suttles, Cristóbal Torriente and Willie Wells, there’s no doubt about the high caliber of play.

As for Rube Foster, who would be elected by the Hall of Fame’s Committee on Veterans in 1981, he would serve his team and the NNL until late in 1926 when illness forced his retirement. He died four years later at 51.

In a Dec. 20, 1930, Chicago Defender editorial, it was written that: “Foster was not a ‘Colored’ baseball man – he was a person of consequence wherever baseball was discussed. He proved to a doubtful public that white people have no monopoly on baseball, either from the playing or box office point of view. He proved that persistency, ability and a knowledge of the game are all the attributes essential to a successful undertaking in any game. Even the color of his skin was no barrier to the success of Rube Foster – it may be said that he profited by it. Certainly he climbed to heights untrod before by a baseball man of his color, and he made some steps that have already proved most difficult to follow.”

In the summer of 1931, after having been without Foster’s guidance for four years, the NNL, which added and subtracted numerous cities to its roster over the years, folded. But ultimately, Foster proved that segregated baseball could be a viable business for Black entrepreneurs.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

The Negro National League is Founded

Pictures tell tale of Negro League legends

Smith’s vision helped clear Jackie’s path to majors

The Negro National League is Founded

Pictures tell tale of Negro League legends