- Home

- Our Stories

- Pictures tell tale of Negro League legends

Pictures tell tale of Negro League legends

A couple of days ago, a man walked into a Chicago restaurant. Normally, no one would have thought much of it. But what he was wearing was striking: A metallic team jacket that read “Grays” across the chest.

Patrons seemed dumbfounded. After a couple of minutes sifting through twenty-some years of accumulated sports knowledge, it finally hit me: “Homestead Grays!”

Blank stares.

“Three Negro League World Series titles? Josh Gibson? Buck Leonard?”

More blank stares. It wasn’t ringing any bells.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Six young professionals in their mid-twenties probably aren’t the best sample size for determining how many of today’s baseball fans have a solid understanding of the Negro Leagues. But because the last organized Negro Leagues baseball games took place in the 1950s, it’s safe to say that younger generations might not know much about it. What complicates things even further is that Negro League stats are scarce on the internet. With the plethora of leagues, schedules and exhibition games, there is no consensus on which statistics should and shouldn’t be counted.

Despite all of this, baseball isn’t willing to let the fabled stories of Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson fade into obscurity. Last season, MLB honored two Negro Leagues teams – Chicago’s Leland Giants and Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays – as the Chicago Cubs and the Pittsburgh Pirates donned their respective Negro Leagues uniforms. And over the past few weeks, the Hall of Fame has made available digitized Negro Leagues photos in PASTIME, accompanied by some background information on the different teams.

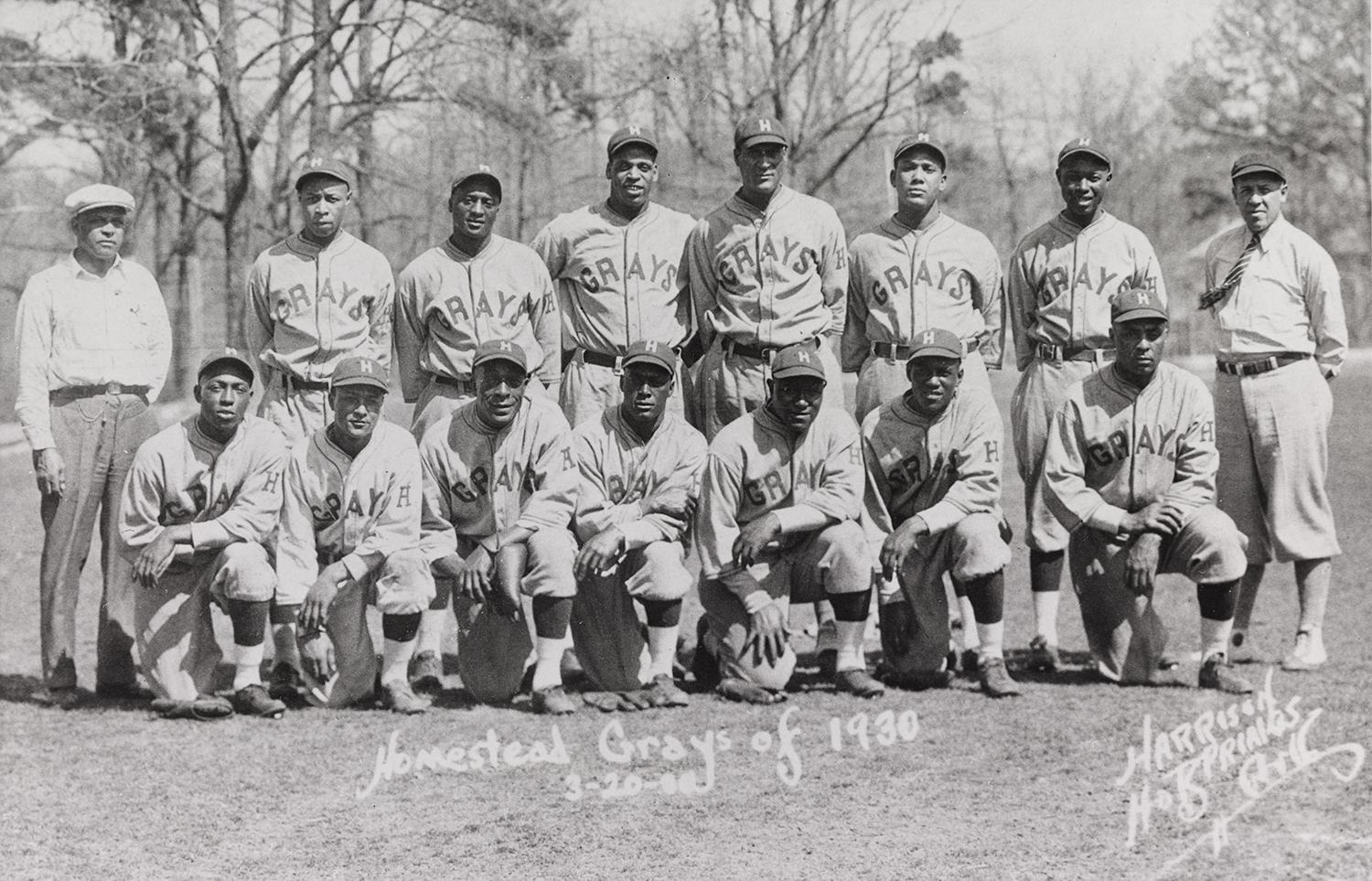

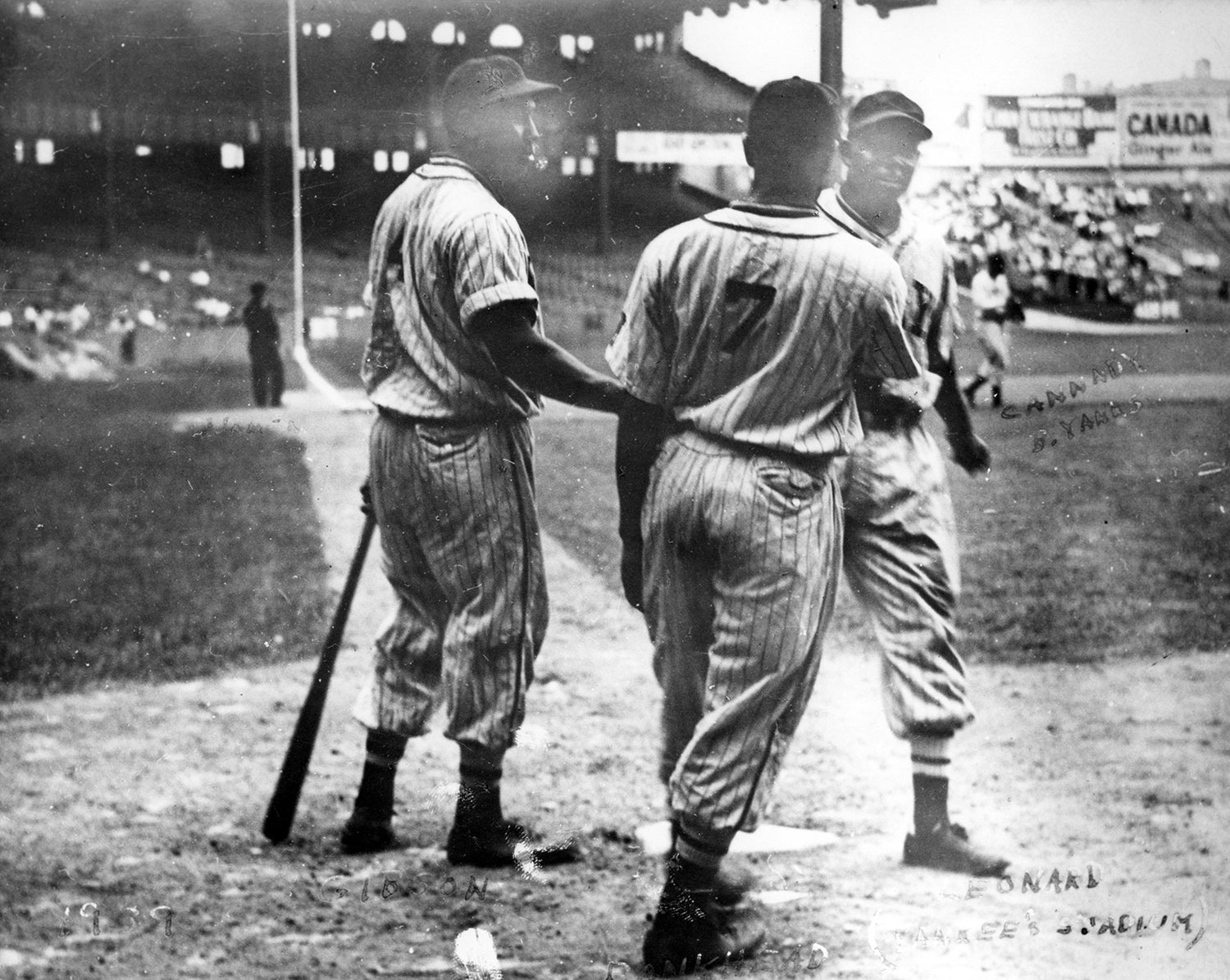

The picture below is taken from the Homestead Grays’ spring training camp in Hot Springs, Ark., in 1930. The Grays were hardly the first club to embark on such a journey. Negro Leagues teams had been heading south since the Chicago Lelands did it in the early 1900s, traveling approximately 6,000 miles under the direction of future Hall of Famer Rube Foster. Four Hall of Famers are pictured on the 1930 team, although the Grays would eventually produce multiple bronze plaques in Cooperstown. On the top row, far right is owner Cum Posey, next to him is player-manager Judy Johnson, fourth from the right stands pitcher Smokey Joe Williams and on the bottom row, to the far right is center fielder Oscar Charleston.

A team photograph of the Homestead Grays taken at Spring Training in 1930 in Hot Springs, Ark. On the top row, far right is owner Cum Posey, next to him is player-manager Judy Johnson, fourth from the right stands pitcher Smokey Joe Williams and on the bottom row, to the far right is center fielder Oscar Charleston. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Twenty-one years prior to the Homestead Grays’ picture, the Chicago Lelands posed for a team photograph. In the top row, to the far left is the rocket-armed center fielder Pete Hill, who Chicago Defender sportswriter Fay Young said “put Negro baseball on the map.” All the way to the right stands Foster, referred to as the “Father of Black Baseball.” Foster set the wheels in motion for the creation of the Negro National League, and became its first president and treasurer. He was simultaneously the manager and owner of the Chicago American Giants (formerly the Leland Giants), who won their first three pennants under his watch.

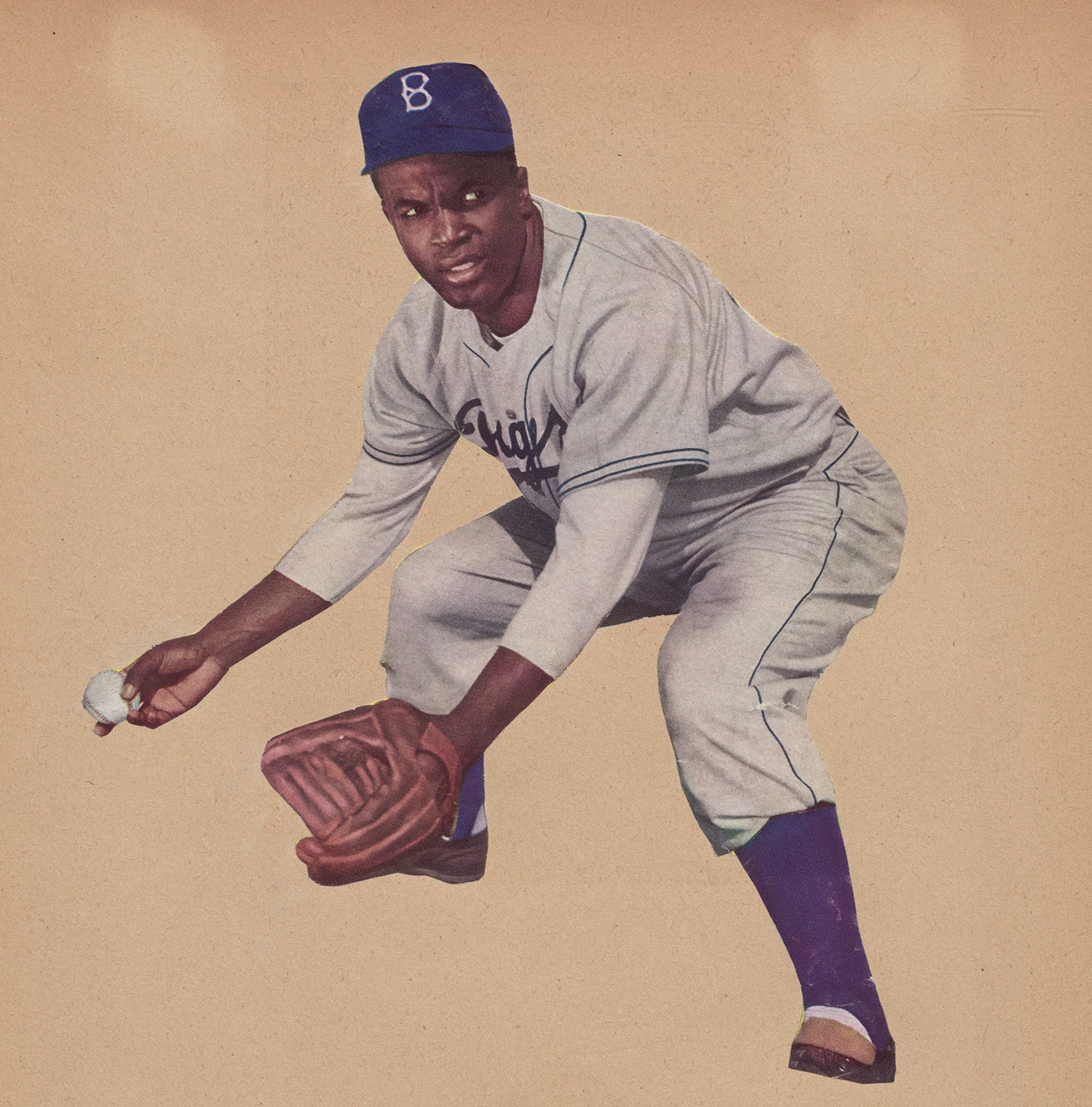

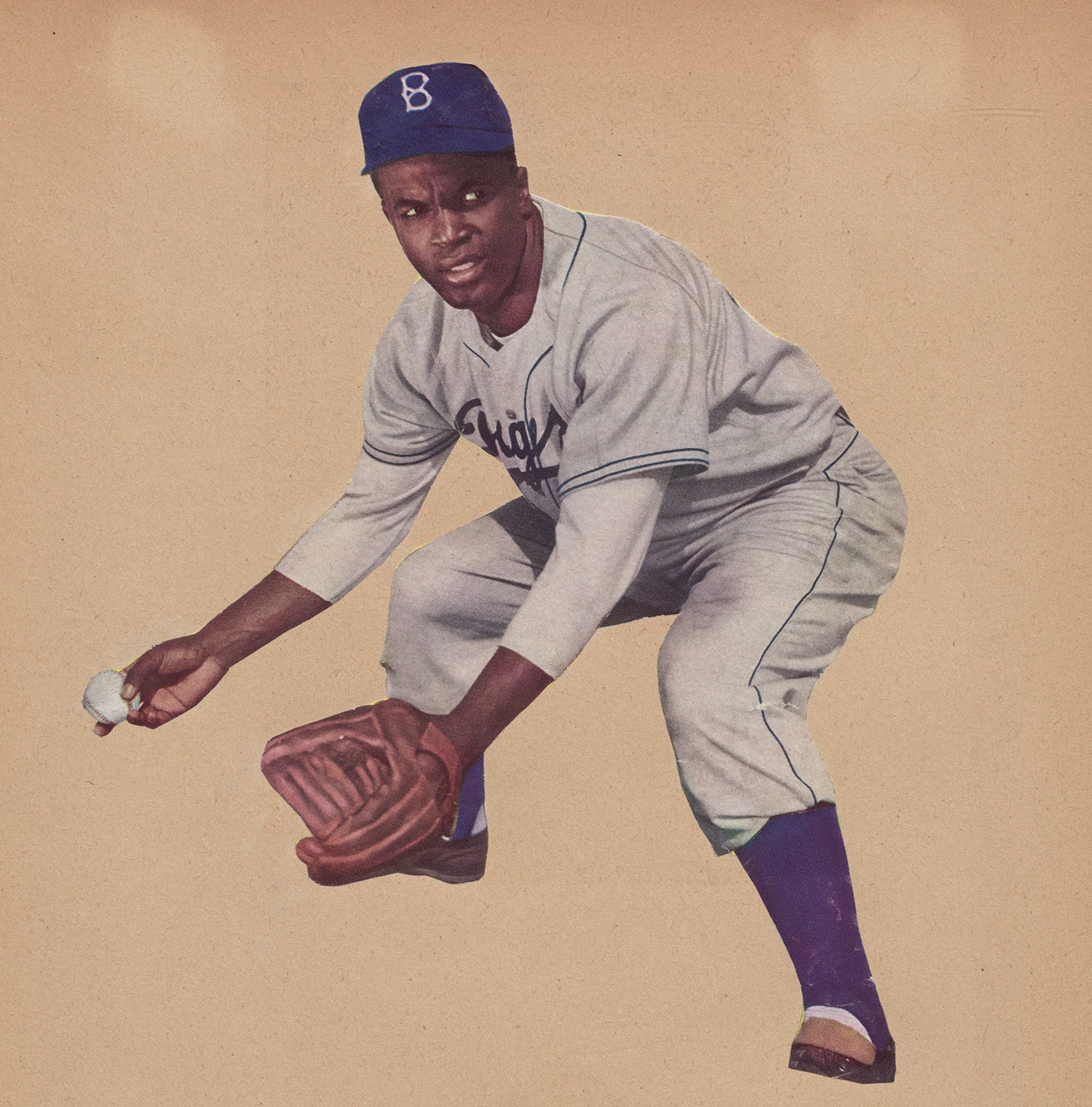

As we witness the debuts of baseball stars hailing from countries as far as South Africa and Lithuania, it’s important to remember the men – and women – who laid the groundwork for Jackie Robinson in 1947. The skill and sportsmanship they showed on the field made them impossible to ignore, but the legacy of the Bucks, Pops and Rubes transcends baseball history.

A 1909 team photograph of the Chicago Leland Giants. In the top row, to the far left is Pete Hill, and all the way to the right stands fellow Hall of Famer Rube Foster. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

“People don’t have to be baseball fans to appreciate this,” Nancy Leazer, a former project coordinator at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, told the Chicago Tribune. “These players found a way to do what they wanted to do—play professional baseball—and do it well, despite the barriers. It’s a wonderful lesson for me, for you, for kids. It’s important social and baseball history.”

Alex Coffey is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

The Negro National League is Founded

Negro Leagues History Digitized in Museum’s Latest Additions to PASTIME

#Shortstops: Words on pictures tell fascinating Negro Leagues story

Negro Leagues photos now available online through PASTIME

The Negro National League is Founded

Negro Leagues History Digitized in Museum’s Latest Additions to PASTIME

#Shortstops: Words on pictures tell fascinating Negro Leagues story