- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1989 Donruss Charles Hudson

#CardCorner: 1989 Donruss Charles Hudson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

By the late 1980s, the Donruss Company had really pulled its act together with regard to the quality of its baseball cards. After struggling with typos, assorted other factual errors and blurred photography in its early sets, Donruss began to hit its stride as the decade progressed.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

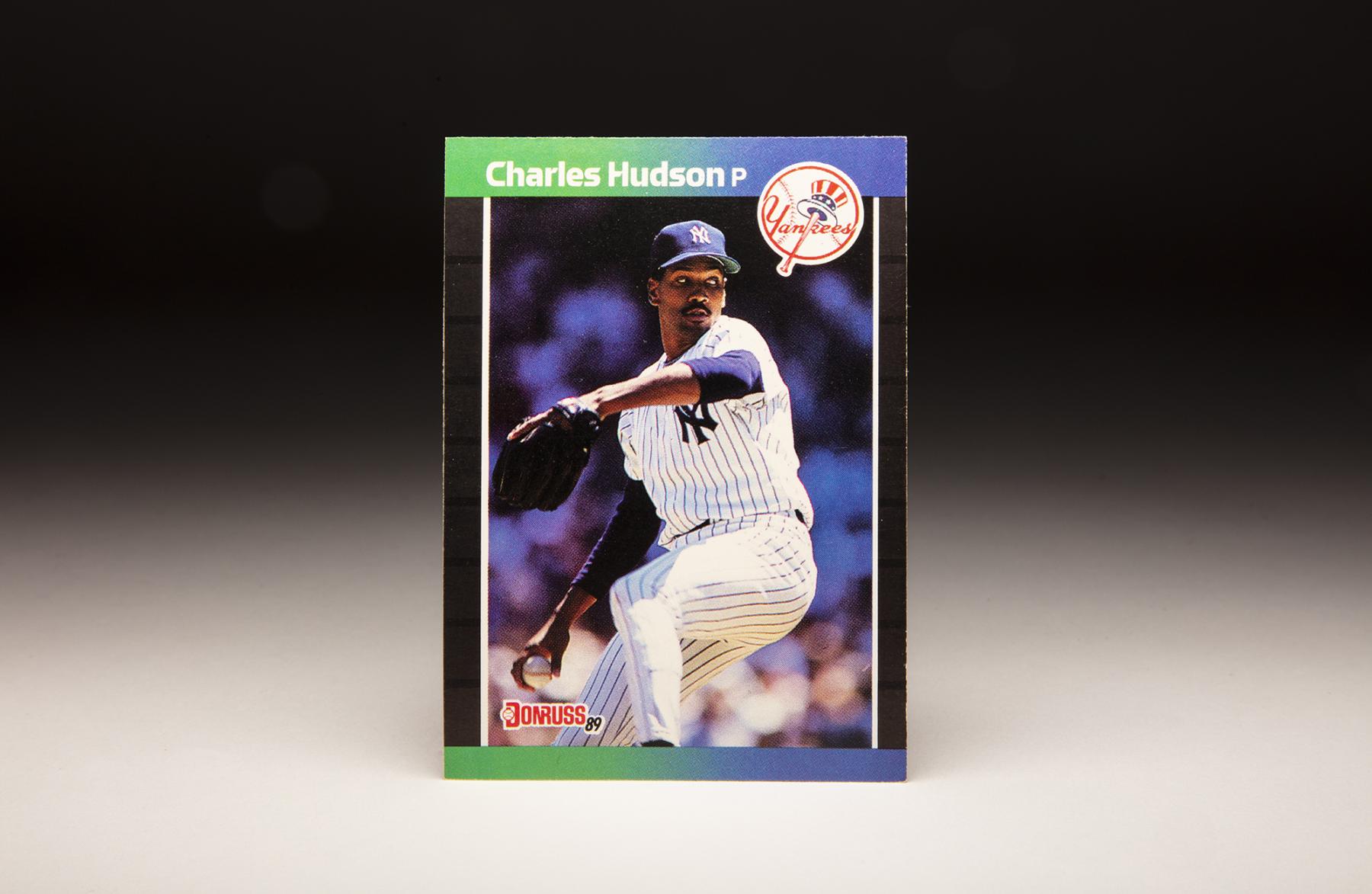

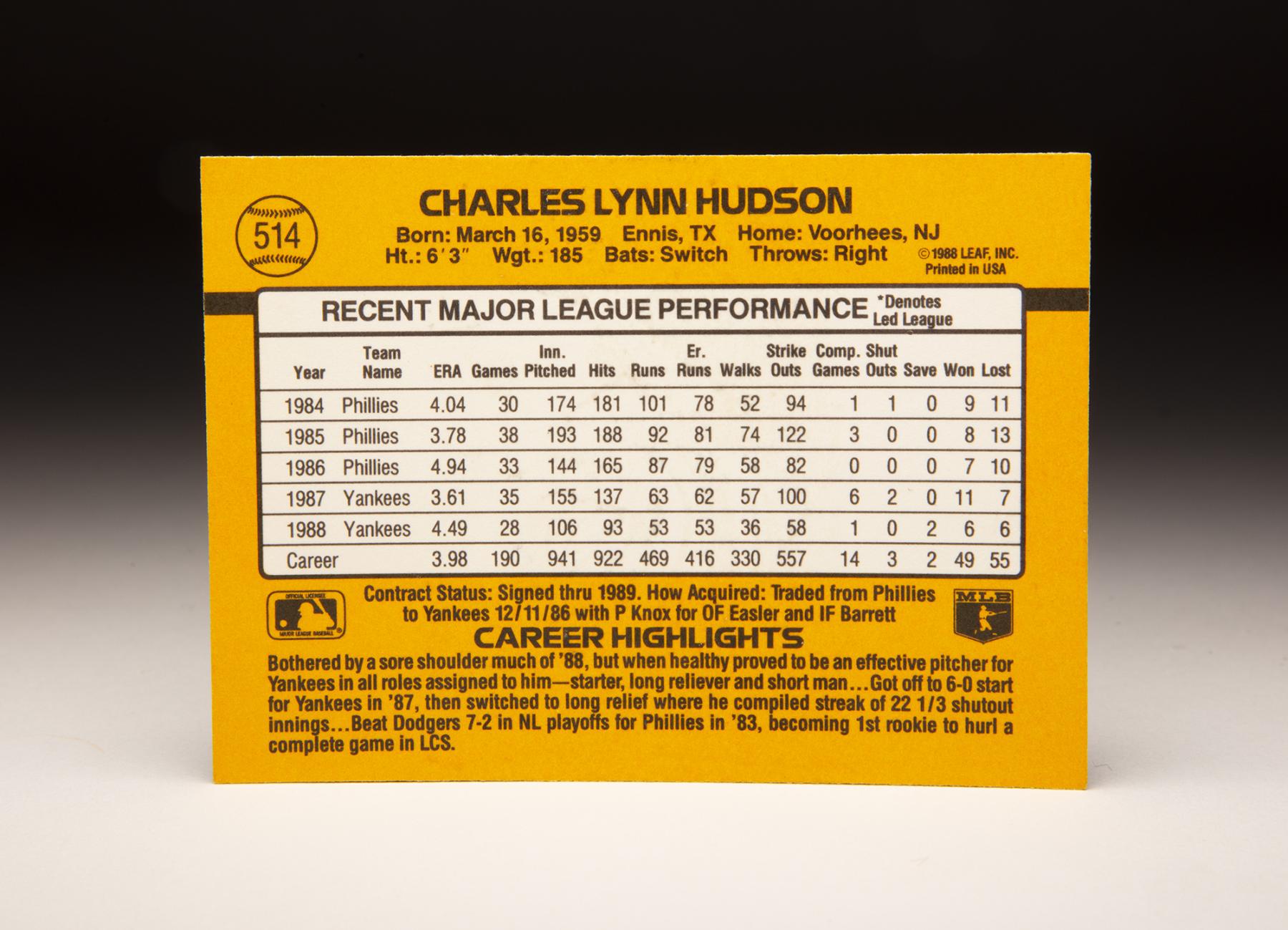

The 1989 set was one of the company’s better offerings – and the card of Charles Hudson one of the more attractive cards contained within the set.

Let’s begin with the design. I particularly enjoy the rainbow effect that Donruss used with the borders at the top and bottom of each card. In the case of the Hudson card, the border begins with a green color on the left before gradually dissolving into a bluish purple motif.

On the sides of the card, Topps used a simple black border, which provides a nice contrast to the colored borders. A thin white line on either side of the card creates a frame for the cards, which feature a nice mix of action photography and posed shots. And Donruss also includes each team’s logo, a practice that has been abandoned by most card companies. It’s particularly nice to see the old logo of the New York Yankees, with its red, white, and blue color scheme, and that old fashioned patriotic hat, propped up on a standard-issue baseball bat. Whenever I see that hat, I immediately think of James Cagney, who wore that same distinctive hat in the 1942 film, Yankee Doodle Dandy, about the life of American composer George M. Cohan.

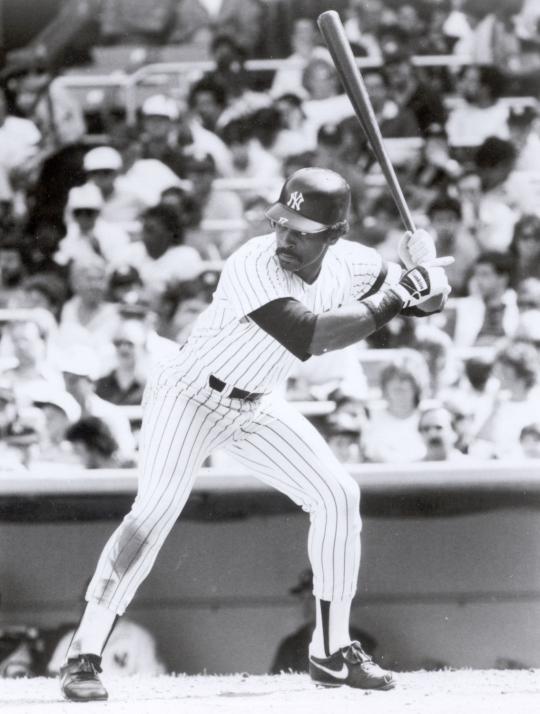

The Hudson card gives us a close-up look of the young right-hander, who is seen in the midst of delivering a pitch during an afternoon game at Yankee Stadium, sometime during the 1988 season. Action cards sometimes obscure a player’s face from our view, but here we are afforded a good look, including the darting of Hudson’s eyes in the direction of home plate. It’s such a clear shot that we can see Hudson gripping the ball in the lower left-hand corner of the image, with his thumb and forefinger coming in contact with the seams.

Hudson is somewhat of a forgotten figure from the 1980s, but at one time he was a highly touted right-hander in the Philadelphia Phillies’ organization. The Yankees acquired him in the hope that he would help them solve their perennial pitching problems of that era, but it never quite worked out that way. He flashed promising talent at times, but injuries, inconsistency, and a brush with the law short-circuited his career. It came to an end in 1989 – the same year that this Donruss card hit the stores for the first time.

Only eight years earlier, Hudson joined the Phillies, who selected him in the 12th round of the MLB draft. Hudson had been a schoolboy legend in Texas, first at South Oak Cliff High School and then at Prairie View A & M. The Phillies assigned him to the rookie-level Pioneer League, where he put up solid numbers in 14 starts and 87 innings. But it was in his second professional season that Hudson bloomed. Assigned to the Class A Carolina League, where he pitched for Peninsula, Hudson outshone all of the other league pitchers. He won 15 of 20 decisions, posted an ERA of 1.85 and struck out 147 batters in 185 innings.

His reputation bolstered by that performance, Hudson earned a jump over Double-A and straight to Triple-A ball in 1983. He made nine starts for Portland of the Pacific Coast League, a league known for high offensive output. With his ERA at 2.67, the Phillies brought Hudson up in midseason. They immediately made him part of the starting rotation, where he fit in nicely with an 8-8 record, a 3.35 ERA and 101 strikeouts. The rookie right-hander impressed the Phillies with his smooth delivery and his live fastball.

The Phillies gave the rookie one start in the NLCS against Los Angeles and two more starts in the World Series against Baltimore. Hudson fared well in his LCS start, picking up a complete-game win while limiting the Dodgers to two runs. But his two starts in the World Series produced far different results. Knocked out early in each game, he allowed eight earned runs in eight and a third combined innings and lost both decisions to the Orioles.

Given his youth and inexperience, the Phillies did not fret much over Hudson’s World Series struggles. After all, he was only 24 years old, and looked like a very capable No. 3 starter behind Steve Carlton and John Denny. Included in the season-opening rotation in 1984, Hudson hoped to build on the success of his rookie season, but instead took two steps back. Limited by injuries, he made only 30 starts, instead of the 35 to 40 that the Phillies had projected. His ERA ballooned to 4.04, a mark that helped limit his win total to only nine, against 11 losses.

The mixed results of his first two seasons had the Phillies wondering what they had in Hudson. The Phillies would use him as a combination starter and reliever in 1985, giving him 26 starts while also pitching him a dozen times in relief. Hudson lowered his ERA to 3.78, but a combination of bad luck and poor run support saddled him with a record of 8-13.

Hudson’s utility role continued in 1986, but this time with near disastrous results. Logging a career-low 144 innings, his ERA soared to 4.94. Exasperated by his inconsistency, the Phillies ran out of patience with him that winter; on Dec. 11, they traded him and a minor league pitcher to the Yankees for veteran outfielder Mike Easler. It was a trade that Yankee manager Lou Piniella opposed, but one favored by team owner George Steinbrenner.

With an aging rotation featuring Tommy John, Ron Guidry and Rick Rhoden, some within the Yankees’ organization envisioned Hudson as a potential solution.

After making one long relief appearance to start the season, Hudson moved into the Yankee rotation and pitched beautifully over the first two months. Responding well to the teaching of Yankee pitching coach Mark Connor, Hudson won his first six decisions and kept his ERA under 3.00. But the good start did not last. Falling into a midseason slump, Hudson lost his spot in the rotation, moved to the bullpen, and then found himself pitching for a spell at Triple-A Columbus. He then returned to the Yankees to finish out the season in the Bronx.

For the most part, Hudson pitched well in 1987, posting a record of 11-7 and an ERA of 3.61. Yet, he was not the answer to New York’s starting pitching issues, as evidenced by his relatively small total of 16 starts.

The Yankees had expected him to be a fulltime starter, but his continuing inconsistency left him relegated to a lesser role. Just like the Phillies, the Yankees wondered why their talented right-hander who had such a live arm and smooth mechanics could remain so enigmatic.

The 1988 season turned out even more frustrating for Hudson and the Yankees. Hudson made only 12 starts and appeared 16 times out of the bullpen in a season shortened by shoulder tendinitis. His 4.49 ERA represented yet another regression, repeating the patterns from his days in Philadelphia.

Hudson returned to the Yankees for Spring Training in 1989, but would not break camp with the team. Devastated by injuries to their infield, the Yankees made a trade with the Tigers for veteran utilityman Tom Brookens, a deal which cost them Hudson in return.

Hudson’s tenure in Motown would turn into a disaster. He made a handful of starts for Tigers skipper Sparky Anderson, but pitched so poorly that he continued to be put back into a long relief role. In August, Hudson’s life hit a low point. Struggling through severe depression for several weeks, he drank heavily one night and became intoxicated, got behind the wheel of his mother-in-law’s Mercury Cougar, lost control, and then slammed the car into a telephone pole. The collision left him with a compound fracture of his left leg and a damaged right knee requiring reconstructive surgery. The injuries sidelined Hudson for the rest of the season. He also received one year’s probation for driving under the influence.

When asked about the accident in the subsequent weeks, Hudson had no memory of climbing into the car, but only of the moments after the crash.

“I remember unhooking my seatbelt because I thought I was home in my garage,” Hudson told the Chicago Tribune. “I looked up and saw a guy above me in the light telling me to stay still, the ambulance was coming.”

Hudson was nowhere near his garage, but had instead wrapped his car around a telephone pole. The accident left him pinned inside of the vehicle. Thankfully, EMS personnel arrived within a few minutes and extricated him from the car.

“I was lucky to be alive,” Hudson said many years later in an interview with New York Daily News sportswriter John Harper. “I still feel lucky just to be here.”

Hudson also told Harper that his pitching struggles had contributed to his ever-growing drinking problem. Given his drinking, along with his accident-related injuries, the Tigers released him at the end of the season. When no other team showed interest, Hudson was forced into retirement.

In some ways, the end of his baseball career was the least of Hudson’s problems. Even after the accident, Hudson suffered another series of setbacks when his mother died, and then one of his cousins committed suicide. After that, he and his wife were divorced.

With his life continuing to bottom out, Hudson eventually turned the corner. Determined to improve his situation, he entered rehabilitation and eventually became sober. He also turned to religion, becoming a born-again Christian.

A couple of years later, the lingering effects of the 1994 baseball strike left Hudson contemplating a return. When the strike persisted into the spring of 1995, Hudson received an invite to attend the training camp of the Chicago Cubs. But his contract contained a clause that stipulated he would not be a replacement player if the strike persisted; he would only pitch for the “regulation” Cubs once the strike ended.

Hudson had decided to attempt the comeback in part because of the efforts of a famed heavyweight boxing champion.

“Once I saw George Foreman come back, I knew I still had a chance,” the 35-year-old Hudson told the Chicago Tribune. “Foreman was right at 40 when he started coming back and he won the championship at 45. I'm coming back, too, if the Good Lord wills it.”

The strike did come to an end that spring, but Hudson lacked the fastball that he had shown in the late 1980s and failed to make Chicago’s Opening Day roster. Since that comeback attempt, Hudson has mostly remained out of the public spotlight, except for his connection to one of the featured characters on the E! Network reality television show, WAGS of Atlanta. Hudson’s daughter, Niche, is the wife of former NFL player Andre Caldwell and appeared regularly on the show until its cancellation in 2018.

These days, Charles is living a quiet life, away from the spotlight and away from baseball. There are few publically available images of him in recent years; almost all of the photos are from his playing days in the 1980s and 90s. And perhaps none is better than the photo that Donruss used for its underrated card set some 30 years ago.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

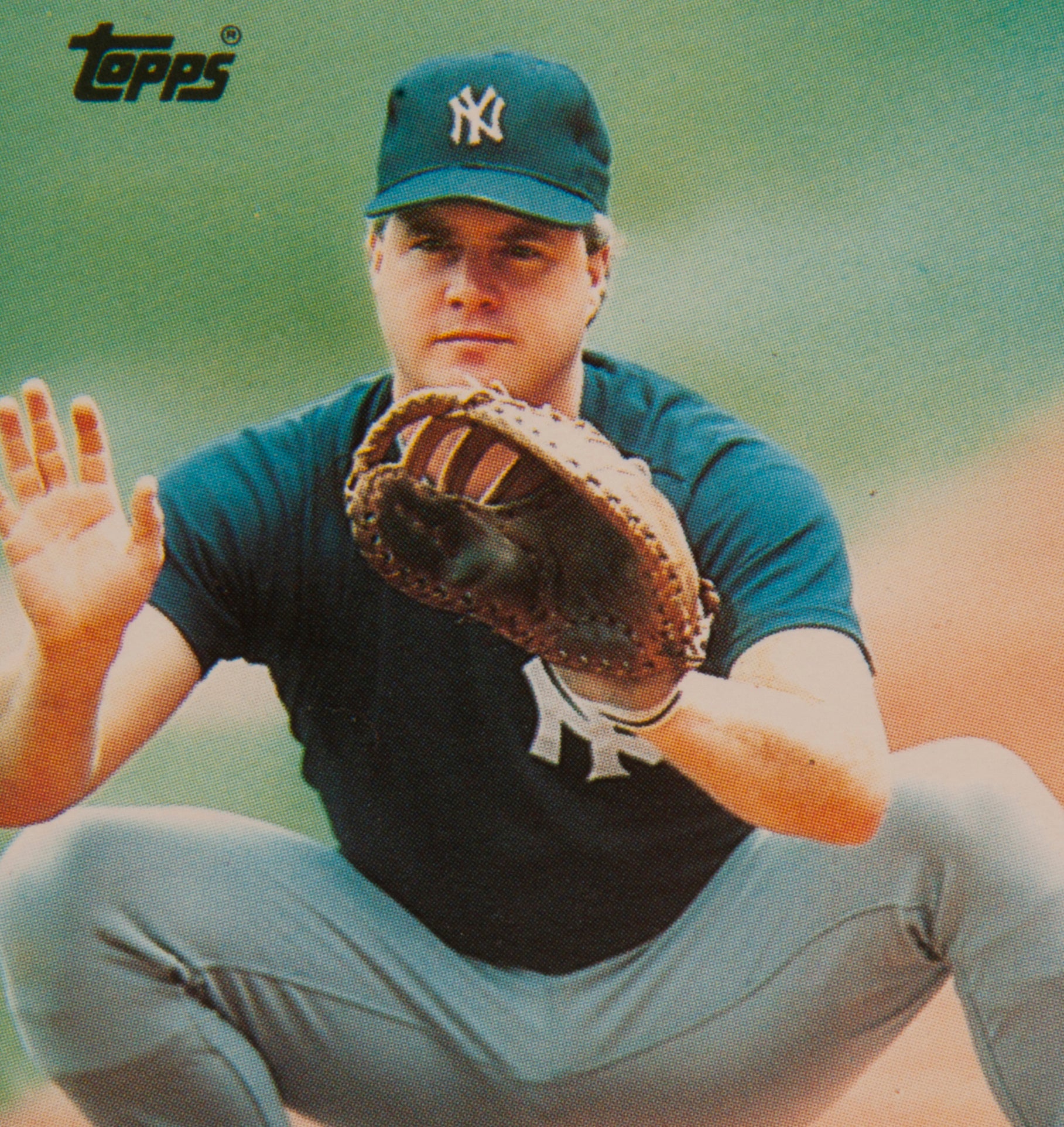

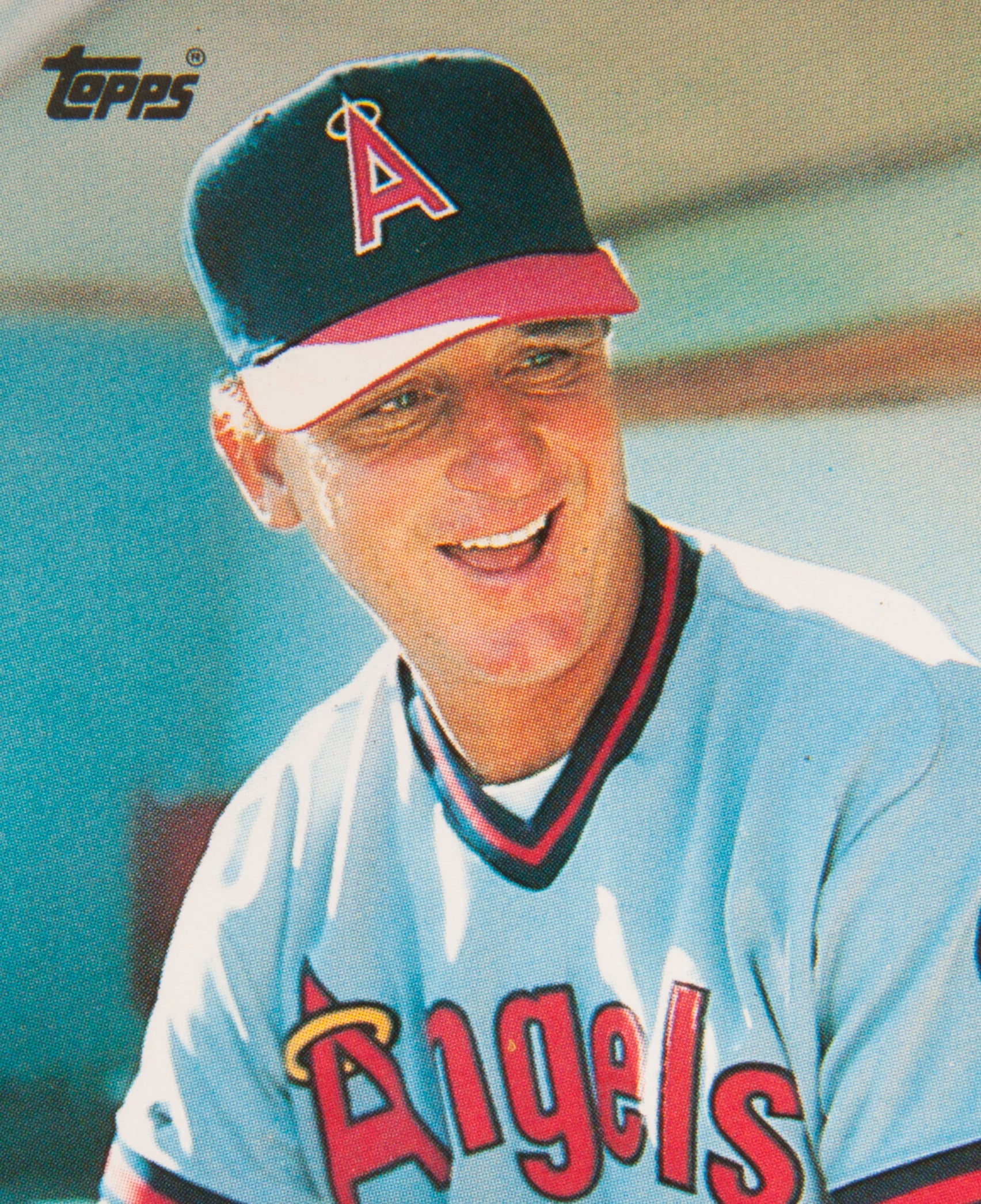

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Jim Lefebvre

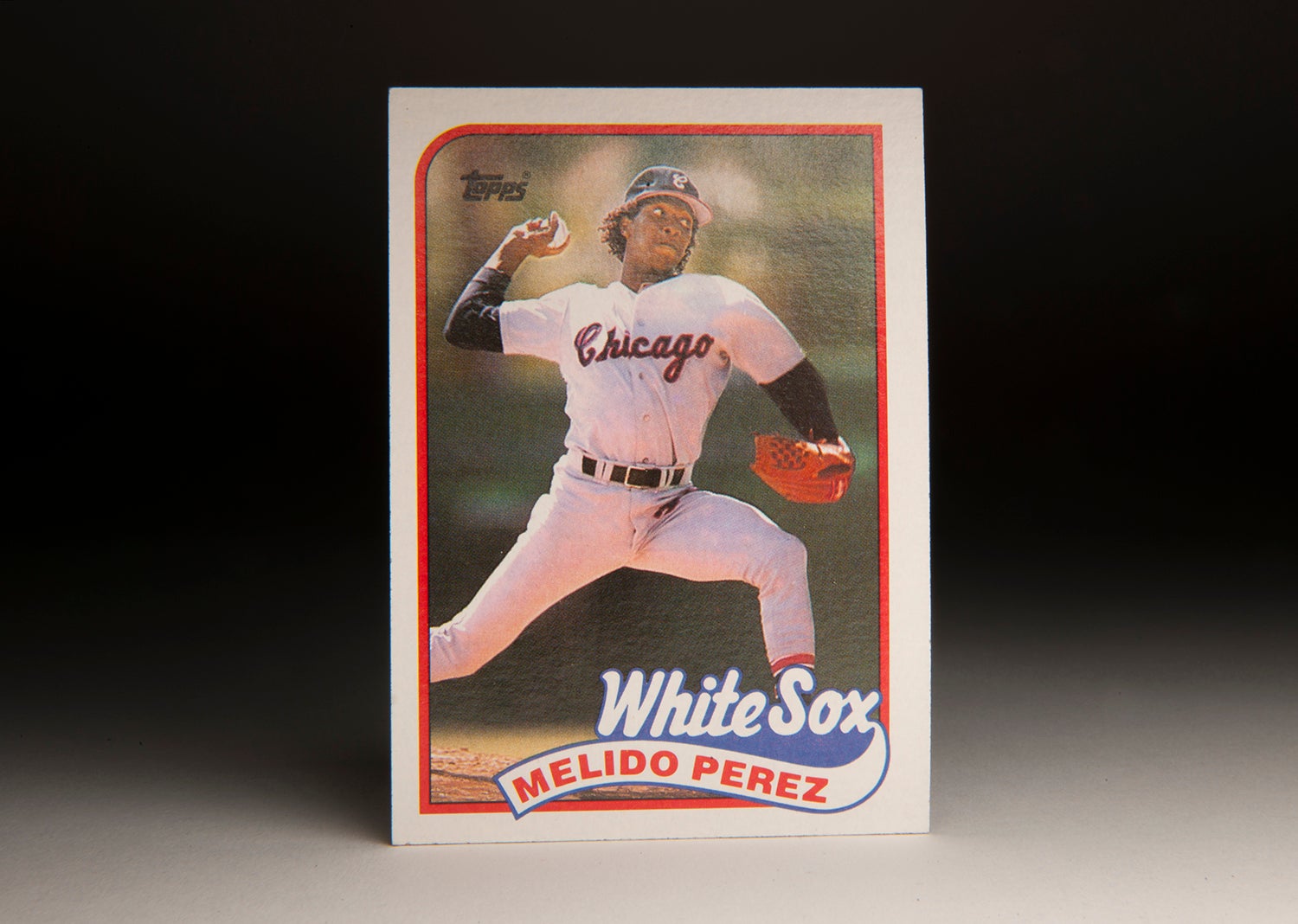

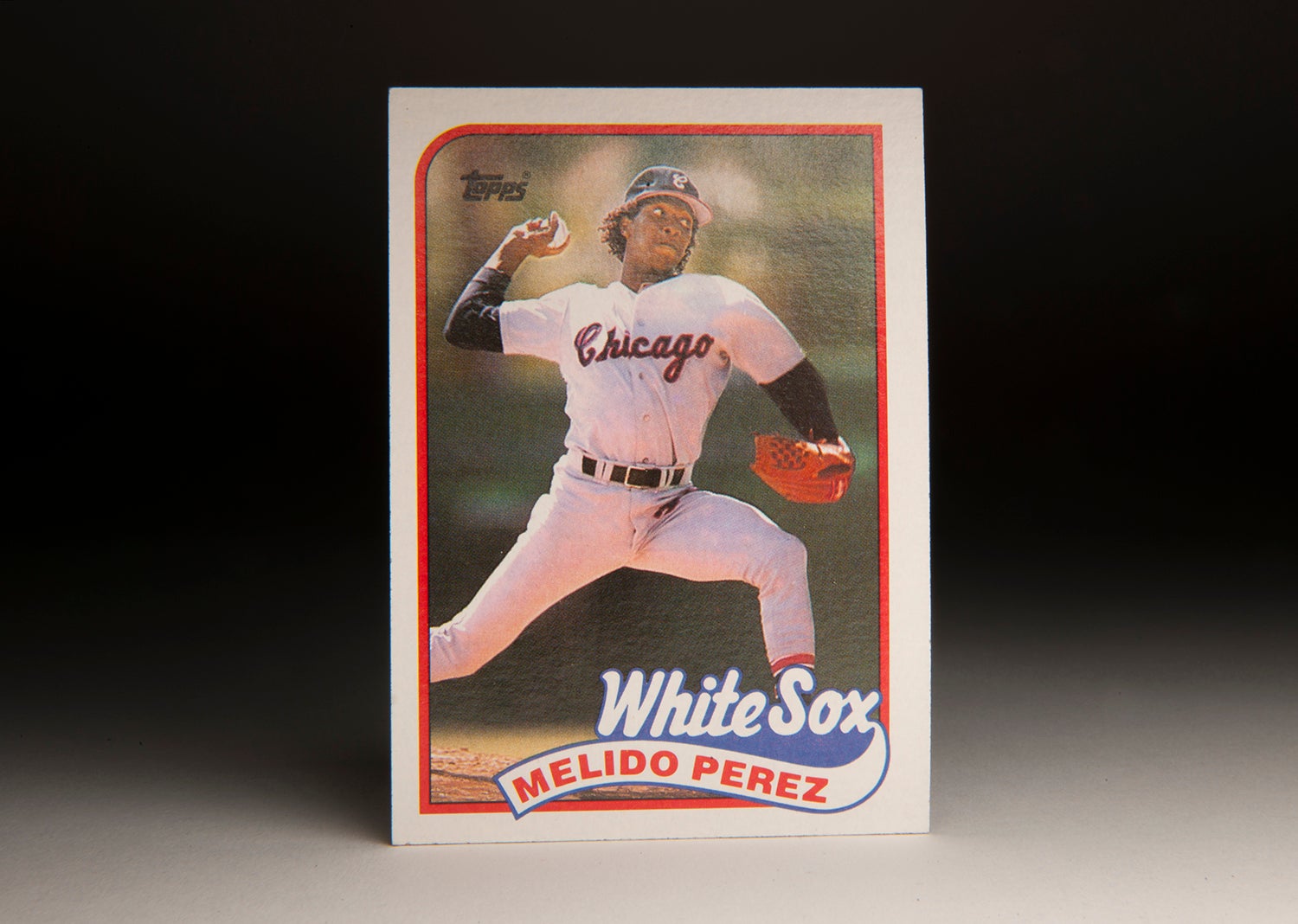

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Melido Perez

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Jim Lefebvre