- Home

- Our Stories

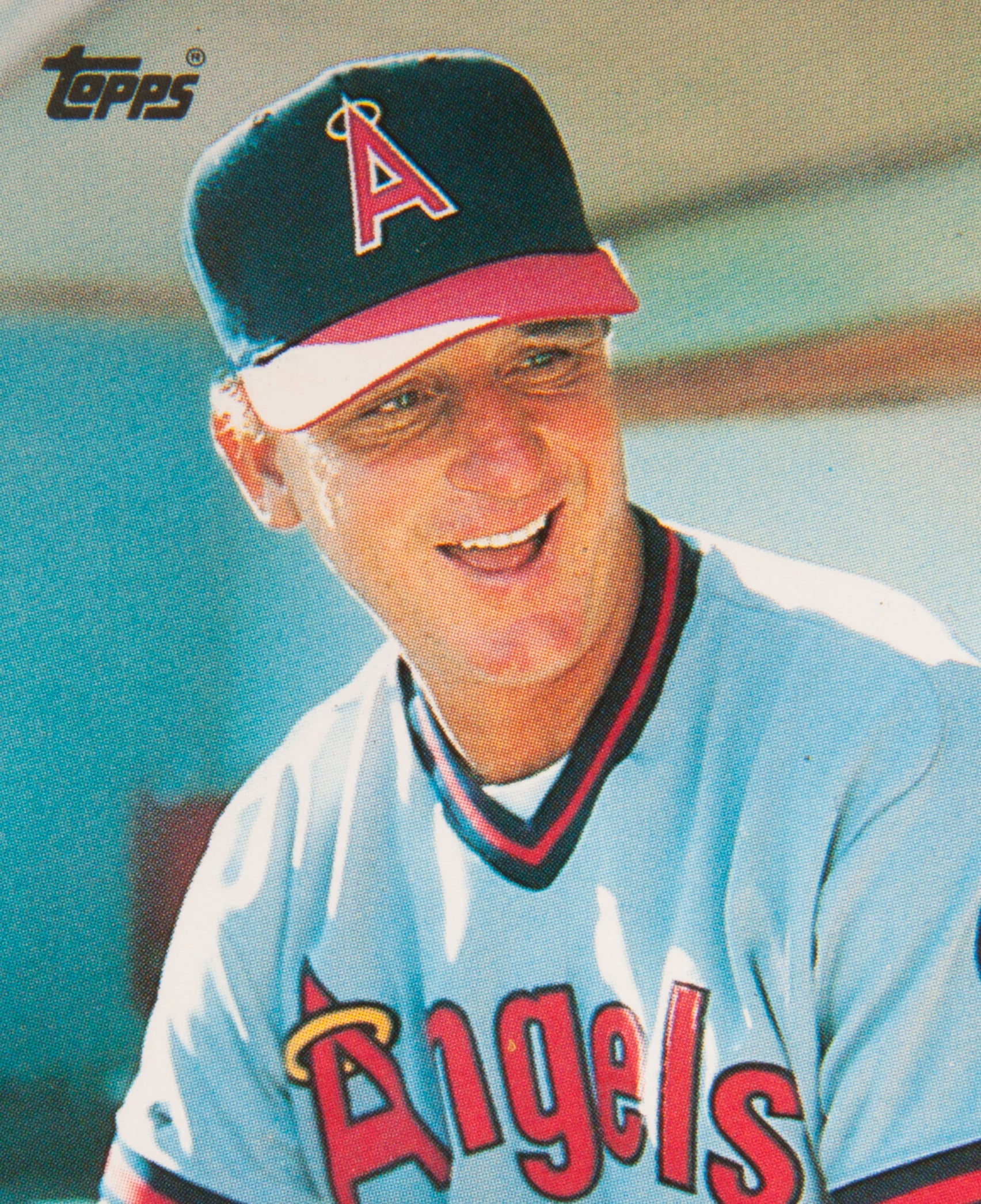

- #CardCorner: 1989 Topps Jim Lefebvre

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Jim Lefebvre

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

If executives in Hollywood ever needed a template for finding an actor who looks like the consummate major league manager, they need look no further than Jim Lefebvre’s 1989 Topps card.

With his square jawline, straight-as-an-edge cap, old-fashioned windbreaker, and arms crossed, Lefebvre has captured the look of someone out of central casting. Striking a pose on the sidelines, Lefebvre looks like the stereotypical rough-and-ready manager of years gone by, chiseled in appearance and forceful in body language, fully prepared to lead his players into the battle ahead.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Lefebvre once pursued an acting career while playing guest parts on a variety of television shows, a career that started during his days as a player and then continued after his retirement from the game. Lefebvre never portrayed a manager in a film or on a TV show, but he did play an island native on a popular sitcom, a henchman, a sergeant on a beloved show about the Korean War, a clown and even a bum. And then later on, he did the managing gig for real, leading three different teams, including the Seattle Mariners, resulting in his appearance on this 1989 Topps Update card.

It is only fitting that Lefebvre (pronounced Luh-FEE-ver) played for the team located in the city that houses Hollywood: The Los Angeles Dodgers. Lefebvre signed with the organization in 1962, receiving an assignment to Reno, the Dodgers’ affiliate at Class C. The switch-hitting Lefebvre made the transition to pro ball look all too easy by dominating the league; he batted .327, hit 39 home runs, and drew 97 walks.

Based on his sensational debut, it was obvious that Lefebvre was ready for a higher league. Bypassing Class B in 1963, he moved up to Single-A, where he continued to impress with 17 home runs and a .283 batting average, while also leading all Northwest League second basemen in putouts and double play. That merited another double jump within the Dodgers’ organization, this time to Triple-A Spokane, where he batted .265 in 55 games in 1964.

Having made a rapid ascension through the system, Lefebvre earned his first taste of the major leagues in 1965. Initially, the Dodgers planned to send him back to Spokane to start the season, but Lefebvre’s play in Spring Training turned heads in his favor. Not only did he make the Opening Day roster, but the rookie known as “Frenchy” won the Dodgers’ second base job, on the strength of his sure hands in the field and his power at the plate. The addition of Lefebvre also allowed the franchise to make some history. With Lefebvre at second, Wes Parker at first, Maury Wills at short and Junior Gilliam at third, the Dodgers fielded an all-switch-hitting infield.

Yet, Lefebvre did more than just become a footnote to an infield of switch-hitters; batting out of the fifth spot in the lineup for much of the season, he hit 12 home runs, drew 71 walks, and also played a solid second base, earning National League Rookie of the Year honors.

Hitting .321 during the stretch run and collecting 20 RBI in September, he also earned some back-of-the-ballot support in the league’s MVP race.

Lefebvre’s contributions helped the Dodgers win the pennant that season, putting them in the World Series against the Minnesota Twins.

Lefebvre started the first three games of the Series, posting a .400 batting average, but he injured his right foot in Game 3, forcing him to miss the rest of the Series.

In his absence, manager Walter Alston turned to utilityman Dick Tracewski, as the Dodgers went on to complete a taut seven-game victory over the Twins. The World Series win left Lefebvre with mixed feelings, happy about the championship, but disappointed that he could not contribute to the actual clinching.

With a Rookie of the Year Award and a World Series ring in tow, an encore might have seemed impossible. But Lefebvre elevated his game further in 1966, raising his batting average 24 points (to .274), doubling his home run production (from 12 to 24) and lifting his OPS from .706 to .793. In particular, he showed improvement as a left-handed hitter, one of the few weaknesses in his game as a rookie. Committing himself to extra time in the batting cage, along with a regimen of weight training, the hardworking Lefebvre’s performance resulted in an All-Star Game nod and an 18th place finish in the National League MVP sweepstakes.

For the second straight year, Lefebvre and the Dodgers won the pennant, earning a place in the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. Lefebvre hit a home run in Game 1 against Dave McNally, but that was one of the few bright spots for the Dodgers during a four-game sweep at the hands of the O’s.

Lefebvre’s first two seasons indicated that he would become a longtime star for the Dodgers. But the 1967 season brought change. Concerned by his lack of range at second, the Dodges moved Lefebvre to third base, where he was not as comfortable.

In an April 25th game against Atlanta, Lefebvre he made four errors, including three of them in one inning.

Offensively, Lefebvre’s production fell off significantly.

Perhaps distracted by the move to third base, his power dipped in ‘67; he hit only eight home runs for the entire season. Some within the organization felt that Lefebvre had put on too many pounds, an opinion supported by one of the Dodgers’ team doctors, who told him flatly to lose some weight.

Lefebvre did as told prior to the 1968 season, but his falloff continued, lingering into the 1969 and 1970 seasons. Nagging injuries played a part in his decline. Used more like a utility man, he appeared in a high of 109 games, failing to hit more than five home runs in any of those seasons. In spite of his diminished playing time, the ever-smiling Lefebvre maintained a good attitude, something noted by Alston during the 1970 season.

“When Jim was out of the lineup,” Alston told Bob Hunter of the Sporting News, “he was one of the best cheerleaders on the bench. He never beefed about not playing, just kept himself ready.” Lefebvre also showed versatility, filling in at second, third, and first base. In 1971, an injury to Billy Grabarkewitz created more playing time for Lefebvre at second base. Given more regular at-bats, he supplied 12 home runs and raised his OPS to a more respectable .698. But Lefebvre could not sustain the improvement in 1972. Once again losing the second base job, he appeared in only 70 games and batted a scant .201, by far the weakest output of his career.

Although Lefebvre was only 30 years old, the Dodgers believed that his days as a frontline player had come to an end. They hoped to bring Lefebvre back as a utility infielder, but he still preferred an everyday role. When the Lotte Orions of the Japanese Leagues expressed interest in him, Lefebvre negotiated a buyout with the Dodgers, who agreed to release him and also received financial compensation from the Orions.

For Lefebvre, the monetary aspects of the Japanese offer were simply too good to turn down. The Orions gave him a guaranteed three-year deal for a total of $300,000, along with a house in Tokyo and expense money, too. Lefebvre accepted the offer and headed to the Far East.

In pursuing Lefebvre, Orions manager Masaichi Kaneda led the charge. Kaneda believed in Lefebvre so much that he told the Japanese media that the ex-Dodger would win the Japanese Triple Crown in 1973. Lefebvre showed good power in his first season in Japan, hitting 29 home runs, but that left him short of the home run title. He also finished well behind in the batting and RBI races.

With his first season a disappointment, Lefebvre hoped for improvement in 1974, but a leg injury short-circuited his season. Disappointed in his performance, Kaneda publicly criticized Lefebvre and sent him to the Japanese version of the minor leagues in midseason. Lefebvre did return to play in the postseason, including the championship round, known as the Nippon Series. He played for first base for the Orions, who emerged as league champions. That made Lefebvre only the second player in history (after Johnny Logan) to win both a World Series and a Nippon Series title.

As a team, the Orions succeeded, but Lefebvre continued to struggle. The situation reached a boiling point during the 1976 season, when Kaneda removed Lefebvre from a game for a pinch-hitter. Upset with the removal, Lefebvre threw one of his gloves in the dugout, nearly hitting Kaneda in the head. Believing that Lefebvre had tried to hit him intentionally, the manager fined and suspended Lefebvre. Later on, the veteran infielder explained that he had simply thrown the glove in anger, but with no intent to strike Kaneda. After a discussion between the two, the manager agreed to drop the fine and suspension.

Remaining with Lotte through the end of the ‘76 season, Lefebvre then retired as a player and returned to the states to work in the Dodgers’ scouting department. He later became a coach with the Dodgers, before moving on to take a position as hitting coach with the rival San Francisco Giants. With the Giants, Lefebvre earned praise for his enthusiasm and work ethic in instructing the team’s core of young hitters.

During the 1980s, Lefebvre resumed a career path that he had first pursued while still playing for the Dodgers in the 1960s. With his good looks, strong physique, outgoing personality, and boundless energy, Lefebvre was a natural to play roles in film and TV. In 1967, he had played a small part in the movie, Riot on Sunset Strip, but also made two far more memorable appearances in popular television shows of the day. Performing on two episodes of Batman, Lefebvre played one of “The Riddler’s” masked henchmen, a character given the name of “Across.” As Lefebvre told the Associated Press about the second episode, “I had a fight with Robin, and he beat me up. According to my script, he beat me up pretty good.”

Lefebvre then took a far different role in the sitcom, Gilligan’s Island, playing what IMDB describes as a “native” on the remote island. Appearing in the latter episode with Lefebvre was outfielder Al “The Bull” Ferrara, one of his teammates with the Dodgers. Dressed in their full native regalia, neither Dodger was quite as recognizable as “The Skipper” or “The Professor.” Taking a break from Hollywood in the 1970s, Lefebvre made a return to the small screen in 1983, when he appeared in a final-season episode of M*A*S*H. Given a speaking role, Lefebvre played an Army Sergeant who informs the camp’s doctors that the general leading his unit is incompetent and unfit for duty.

From there, Lefebvre went on to appear as a clown on the comedy Alice, made two appearances on the critically acclaimed hospital drama St. Elsewhere and portrayed a street bum on Knight Rider, among other roles. In 1991, Lefebvre made his final TV appearances, as he enjoyed a recurring three-show guest arc on the soap opera, Santa Barbara.

In and around all of these television roles, Lefebvre still found time to pursue a remaining goal in baseball: Becoming a manager. That dream came true in 1989, when the Mariners hired Lefebvre to replace Jim Snyder. Lefebvre led the Mariners to respectable finishes in ’89 and 90, followed by an 83-79 finish in 1991. Despite the Mariners’ improvement in the latter season, they organization fired Lefebvre at season’s end.

Lefebvre did not remain out of work long, as the Chicago Cubs hired him that winter. After leading the Cubs to a 78-win season in 1992, he guided the club to 84 wins in 1993, but once again a record of better than .500 failed to save his job. Lefebvre would receive one more chance at managing in 1999, when the Brewers hired him to replace Phil Garner on an interim basis toward the tail-end of the 1999 season. When the season came to an end, Lefebvre gave way to Davey Lopes.

Although he’s now retired from Organized Baseball, Lefebvre has found other ways to extend his association with the game. He has twice managed the Chinese National Team in the Olympics and also led Team China in the 2006 World Baseball Classic. For someone like Lefebvre, who had played in Japan and developed an affinity for the culture, the desire to return to another Asian country in a managing role came naturally.

“Developing baseball in China is a long-term project,” Lefebvre told writer Murray Greig for the web site, Baseball Savvy.com. “Our ultimate objective is to make it part of the culture, to get kids playing in the streets. It’s happened here with basketball and it can happen with baseball. We want to develop homegrown stars, too.”

Lefebvre’s interest in tapping the potential of baseball in China is just the latest goal for one of baseball’s most well-rounded people. After all, he’s done just about everything else, from playing the game in the majors and in Japan, to coaching and managing, to appearing in Batman and Gilligan’s Island. In trying to discover renaissance men within the game, it’s easy to find at least one by examining the diverse paths taken by Jim Lefebvre.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

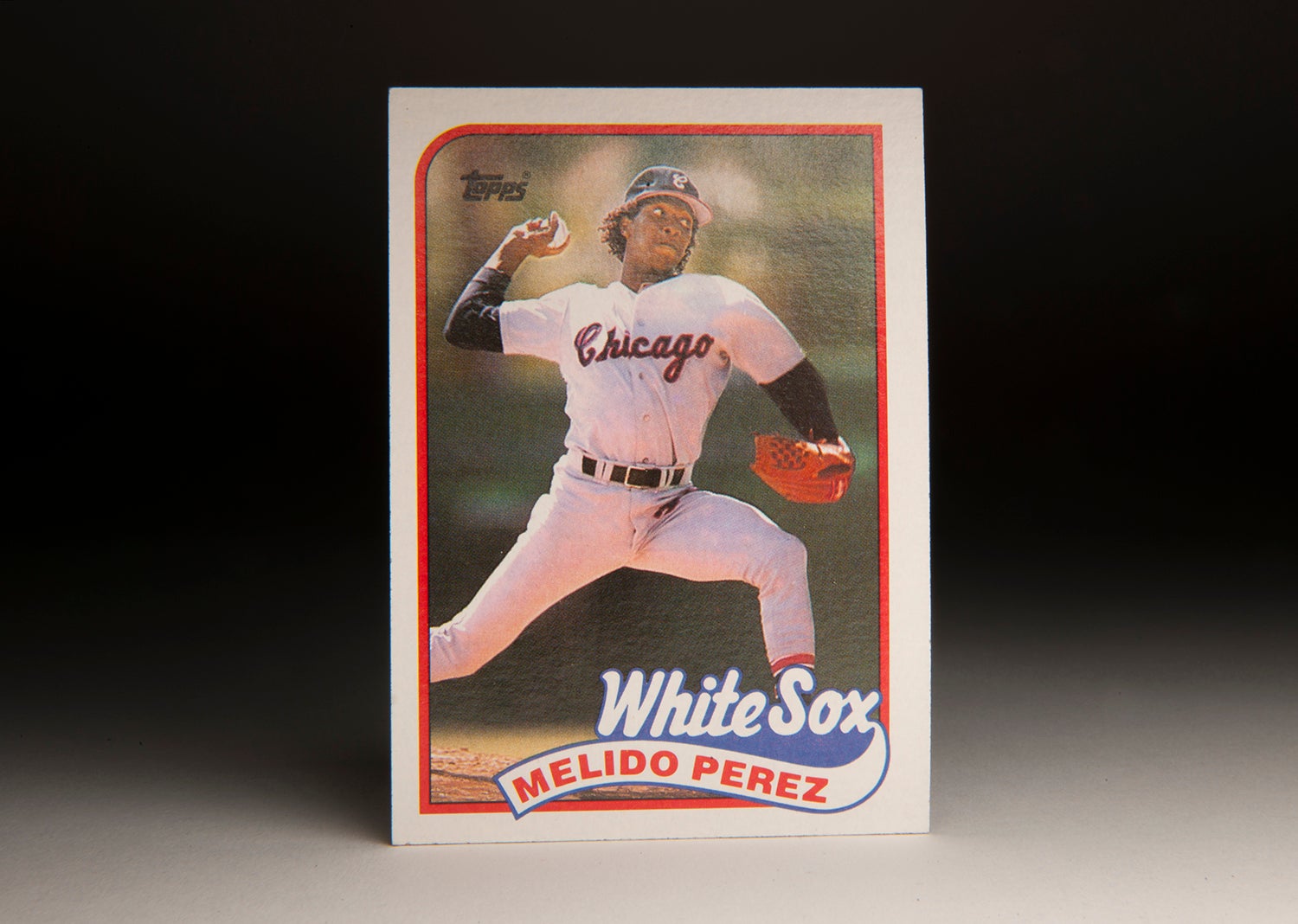

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Melido Perez

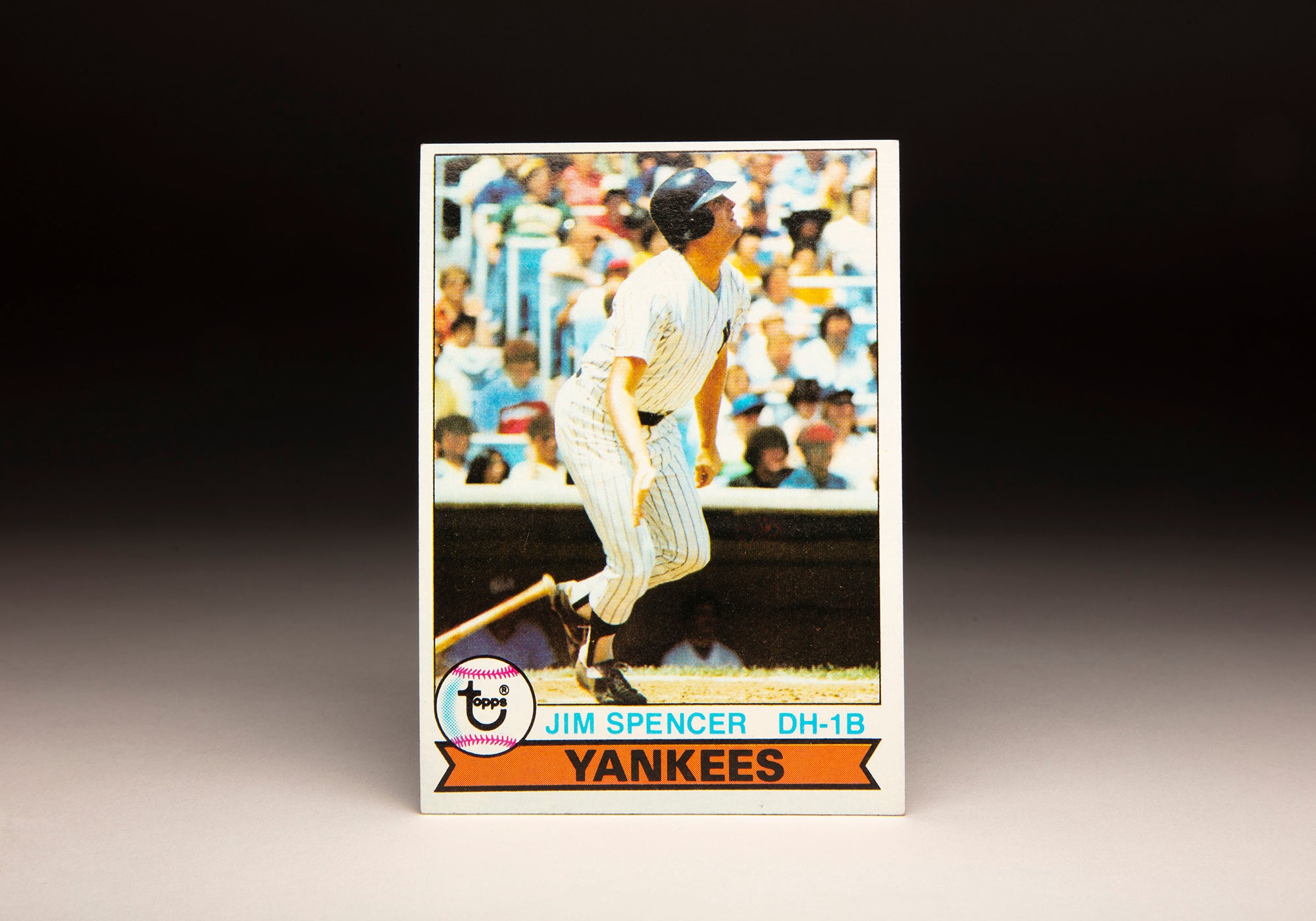

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Spencer

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Melido Perez