- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Spencer

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Spencer

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

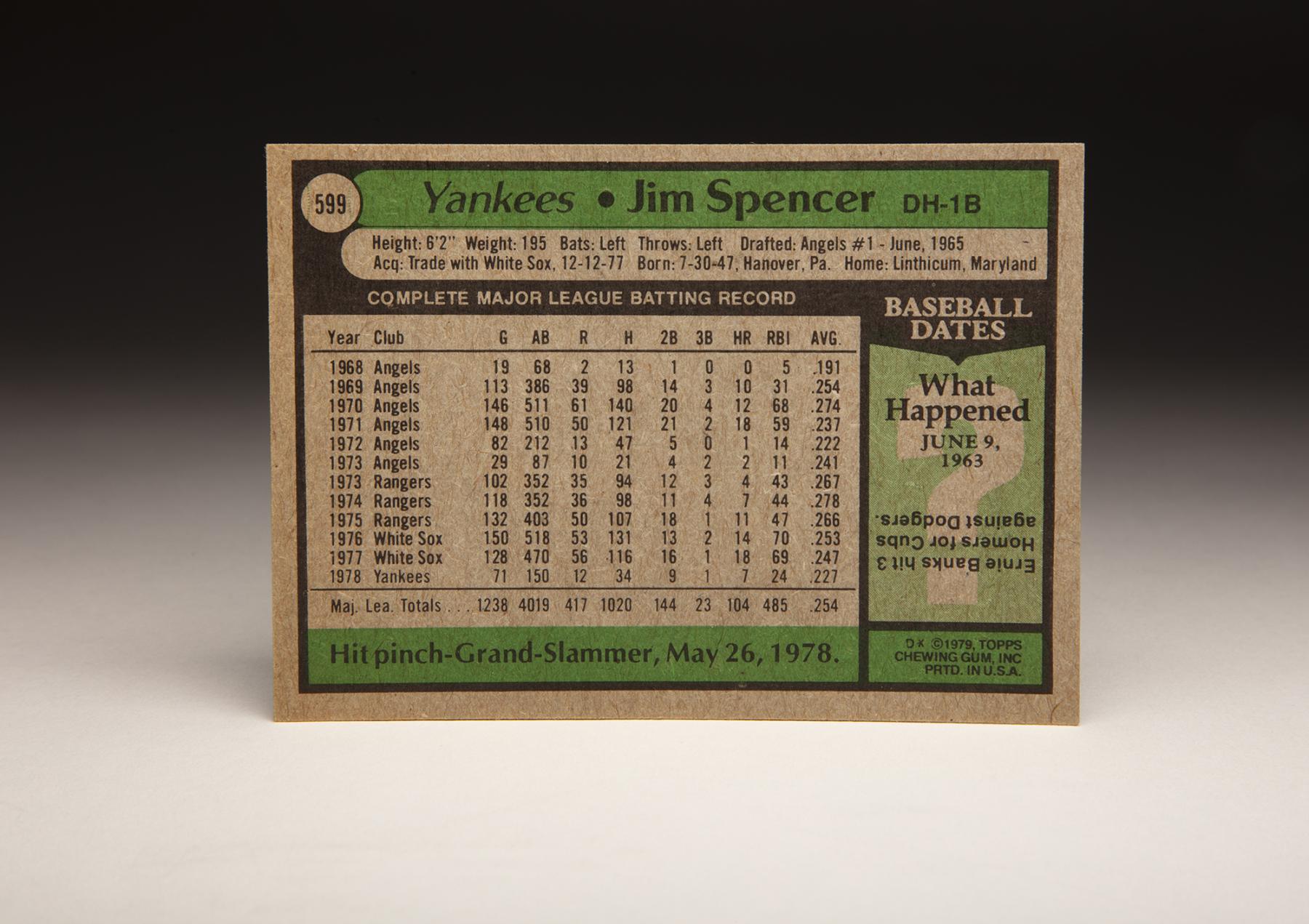

By 1979, the Topps Company sensed that its days as a monopoly were coming to an end. Four years earlier, Fleer had filed suit against Topps, believing that it was time for the courts to force the Players Association into making contracts with other card companies. Even though Fleer did not win the suit until 1980, Topps realized that its branding was important.

So in 1979, for the first time ever, Topps printed its logo onto the front of each card, placing the label in the lower left-hand corner of the card. That decision would prove prescient; by 1981, Fleer and Donruss began producing their own sets of cards. It was now becoming important for each card company to identity itself on the front of the card, and not just in fine print on the back.

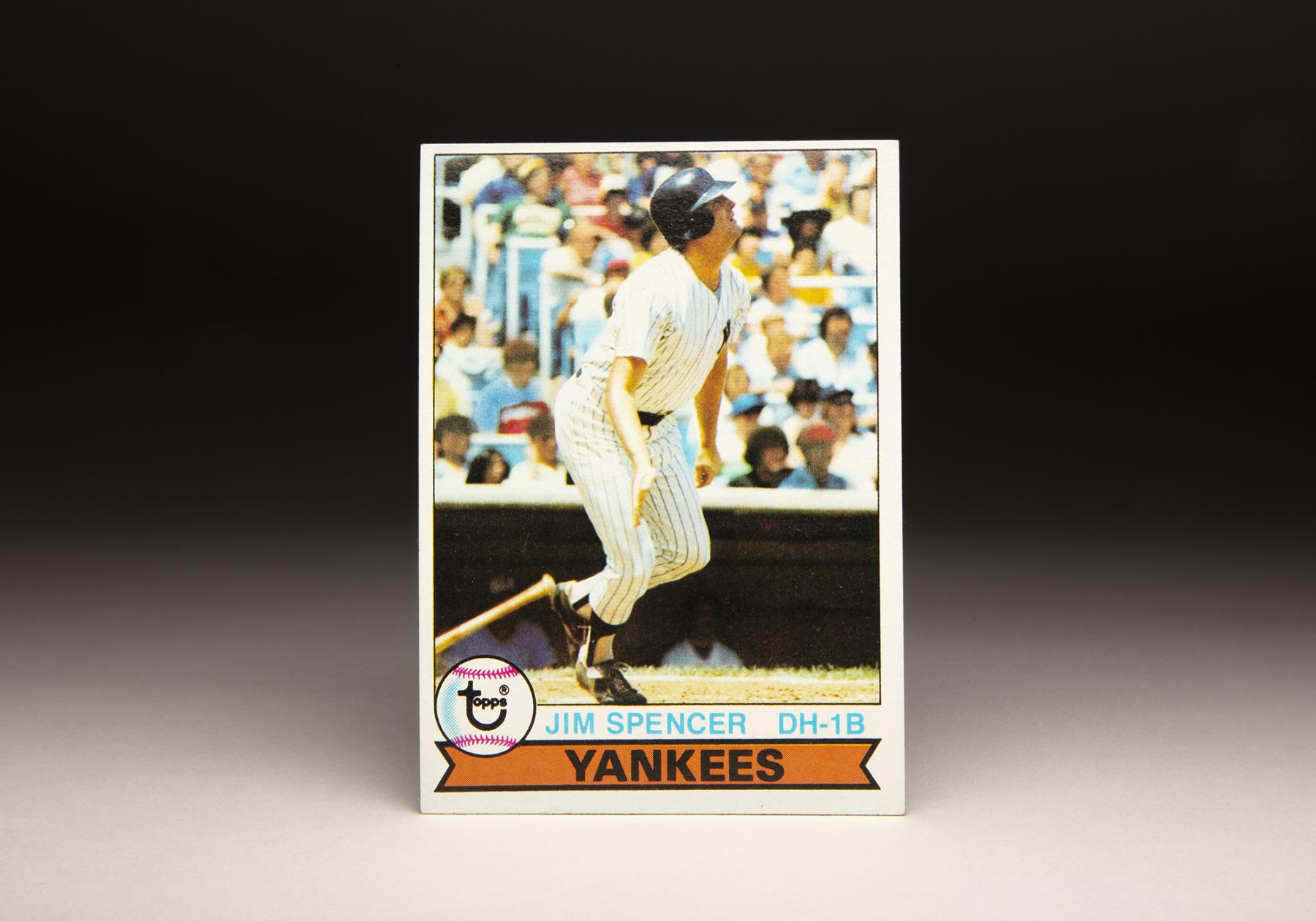

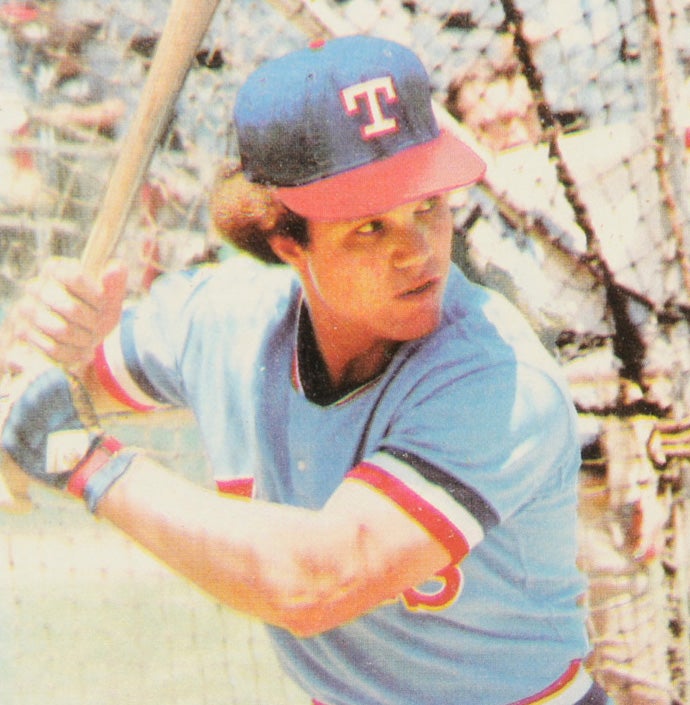

Aside from the inclusion of the old Topps logo, the 1979 Topps set has never received much public admiration, but it’s a decent set with a simple, unoffending design and a fair share of above-average action photography. The card of Jim Spencer is one of the better selections in the set.

We see Spencer, wearing an ear-flap helmet while playing in an afternoon game at Yankee Stadium during the summer of ’78, finishing his swing and dropping his bat to the ground. His distinctive physique is in full view: a high-waisted build with a bit of a paunch around the middle. He has thin arms, belying the above-average power that he generated, particularly against right-handed pitching.

The card makes me wonder about the outcome of the at-bat. Spencer appears to be looking straight ahead, in the general direction of center field. The optimist might say that Spencer has just hit a home run. The realist, based on the relatively mundane reaction of the fans at Yankee Stadium, might be tempted to say Spencer has delivered nothing more than a routine fly ball to the center fielder.

Spencer is a player who has become somewhat forgotten since retirement, unless you’re old enough to have seen him play. For the most part, he was a platoon player; only once did he appear in as many as 150 games in a season. Fair or unfair, he always dealt with the familiar rap: “He can’t hit left-handed pitching.” As a platoon player, Spencer might have struggled to stick with a major league team today. In the modern game, most teams carry 12 or 13 pitchers, leaving little room on their bench for platoon first basemen and pinch-hitting specialists.

Yet, in the 1970s, Spencer was a pretty fair country ballplayer for the Yankees, Chicago White Sox and a couple of other teams. A two-time Gold Glove Award winner, he was an excellent first baseman with soft hands and an ability to pick throws out of the dirt. He fielded his position with smoothness and rhythm, despite having that non-athletic build. With that big waist and those short, lean arms, Spencer provided the visual antithesis to more athletic-looking players like Dave Winfield and Derek Jeter, who became Yankee stars in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively.

While not a great hitter, Spencer could be productive against right-handed pitching. And with his pull swing, he found the short porch at Yankee Stadium to his liking. All in all, you could win with a Jim Spencer playing a significant role on your bench.

The Yankees did just that in 1978, when they won the world championship, and in 1980, when they reached the postseason. Spencer played for both of those teams.

Long before he joined the Yankees, Spencer’s professional career began with the first amateur draft of 1965.

Highly touted at Andover High School in Maryland, he drew some interest from the team he followed as a youth, the Baltimore Orioles, but it was the California Angels who selected him with the 11th pick of the first round.

As a 17-year-old rookie, Spencer was overwhelmed by his first taste of minor league pitching. He batted only .223 with two home runs for Quad Cities, a Class A team in the Midwest League.

The Angels refused to let those numbers fool them. They liked his smooth swing and power. In 1966, they bumped him up to Double-A El Paso of the Texas League. Settling down as a sophomore, Spencer showed patience, made better contact, and belted 16 home runs.

Spencer remained at El Paso for the next year and a half; he improved in 1967, and improved some more in ’68. By the middle of ’68, he was dominating the Texas League, with 20 home runs and a .906 OPS over 135 games. He was also a player who hustled and played the game in a fundamentally sound way. Allowing him to bypass Triple-A, the Angels brought him to Anaheim in September of ’68.

Spencer made a good first impression on his manager, Bill Rigney. “I like what I’ve seen,” Rigney told the Sporting News. “He’s the best defensive first baseman we’ve had since Vic Power.”

With the bat, Spencer’s game showed a need for improvement. Appearing in 19 games down the stretch, he hit just .191 in 73 plate appearances and did not hit a home run.

That winter, the Angels decided to dangle Spencer as part of an effort to acquire a more established first baseman. Engaging the Philadelphia Phillies in trade talks for star Dick Allen, the Angels offered a package centered on Spencer. But the Phillies turned down the offer. So the Angels protected Spencer from the upcoming expansion draft and brought him to Spring Training with the idea that he would compete for the starting first base job. Spencer did not hit well that spring; prior to Opening Day, the Angels decided on veteran Dick Stuart, who hadn’t played in the major leagues the last two seasons, and sent Spencer to Triple-A Hawaii for additional prep work. By late May, the Angels were ready to make a change.

Dissatisfied with the play of the aging Stuart, the Angels brought Spencer back to California and made him their regular first baseman. Spencer batted .254 and walked only occasionally, but did flash some power (10 home runs). He also played a phenomenal first base.

Over each of the next two seasons, Spencer continued to defend his position with poise and style while improving his power and his patience. In 1970, he won the American league Gold Glove Award. In 1971, he clubbed 18 home runs and drew 48 walks. He appeared to be on his way.

In 1972, an injured knee suffered in a home plate collision curtailed Spencer’s progress. He eventually lost his first base job to slugging Bob Oliver. By the end of the season, Spencer was so dissatisfied with his manager, Del Rice, that he considered retirement. Instead, he decided to report to winter ball in the Dominican Republic, where he played for future Hall of Fame manager Tommy Lasorda.

By the time Spencer reported to Spring Training in 1973, he had lost 10 pounds and strengthened his bad knee. But once the regular season started, Spencer showed little power. In May, the Angels decided to move in a different direction: trading Spencer to the Texas Rangers for slugging first baseman Mike Epstein.

Over the next two and a half seasons, Spencer split his time between first base and DH for the Rangers. He made the All-Star team in 1973, but showed relatively little power. In 1974, he sprained the arch in his foot, undermining his production. By the end of the 1975 season, the Rangers believed that their future at first base rested with Mike Hargrove, a better hitter than Spencer.

At the 1975 Winter Meetings, the Rangers shopped Spencer. On Dec. 10, they sent Spencer and $100,000 in cash back to the Angels for veteran right-hander Bill Singer.

In actuality, the Angels had no interest in a long-term reunion with Spencer. The following day, they traded him again, sending him to the White Sox for aging slugger Bill Melton and pitching prospect Steve Dunning.

Spencer proved a good fit for the White Sox, a team that needed power. In 1976, only two White Sox reached double figures in home runs: Spencer and Jorge Orta. That same summer, Spencer impressed players on both the White Sox and their opponents by his willingness to take a stand for Cleveland Indians coach Rocky Colavito. During a recent game between the White Sox and Indians, Colavito had been accused of bumping one of the umpires. Call in to testify on the matter by American League president Lee MacPhail, Spencer explained what he saw: That the umpire had baited and antagonized Colavito. Spencer’s testimony resulted in a favorable sentence for Colavito.

The following summer, Spencer emerged as a key part of a famed group of White Sox called the “South Side Hit Men,” a hard-hitting team that featured Oscar Gamble and Richie Zisk. Those Sox surprisingly contended for supremacy in the American League West. Making a decision to go with a larger, heavier bat, Spencer hit 18 home runs. He also won his second Gold Glove Award.

As a fielder, Spencer did everything well. With his quick first step, he covered ground to either side. He skillfully handled throws in the dirt. He was arguably the American League’s best first baseman at making throws to second and starting the 3-6-3 double play. And he played the old school way, catching throws with two hands, not the one-handed way that had become fashionable by the 1970s.

As well as Spencer played for the White Sox in ‘77, the franchise was looking to cut costs while making room for a younger first baseman in Lamar Johnson. That winter, the Sox sent Spencer to the Yankees for cash and two minor league pitchers, neither of whom was rated as a top prospect.

“It grieved me to sell Spencer,” owner Bill Veeck told sportswriter Jerome Holtzman. “He’s a great player to have around a club, a fine competitor, strictly a professional. But we had to open up the job for Lamar.”

In the meantime, the Yankees viewed Spencer, who was still only 29, as a player who could provide backup to Chris Chambliss at first base while also serving as an occasional DH.

That was the plan, but injuries limited Spencer. He came to bat only 166 times, making him a secondary player on that legendary 1978 Yankees team.

Spencer would play a far more prominent role in 1979, on a team that would deal with underachievement, a cascade of injuries, and the tragic death of team captain Thurman Munson. Lost amidst a difficult season for New York was the performance of Spencer, who led the ’79 Yankees with an OPS of .970. In just 295 at-bats, Spencer clubbed a career-high 23 home runs.

After the season, the Yankees traded Chambliss, clearing out more playing time for Spencer. He played a complimentary role on that 1980 team, a club that won 103 games and remains underrated in Yankee lore, if only because of a three-game playoff sweep at the hands of the Kansas City Royals.

While Spencer produced a few highlights in Yankee pinstripes, several factors hurt him during his time in the Bronx. At one point, he became involved in a nasty dispute with the front office. Strangely, Spencer signed a contract that included a clause guaranteeing his presence in the lineup against a right-handed pitcher. Such clauses have always been illegal and therefore unenforceable, but Spencer and his agent complained when his managers left him out of the lineup against certain right-handers. Spencer’s complaints drew criticism from some writers within the New York media.

Unhappy with his role in New York, Spencer asked the Yankees to trade him prior to Opening Day. During the spring of 1981, the Yankees satisfied that request, giving up Spencer and cash for Jason Thompson, at the time a budding star with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn then voided the deal, principally because the Yankees were sending too much money – and not enough actual talent – back to the Pirates. When the Yankees were unable to restructure the deal, Spencer returned to New York, creating a letdown for Yankee fans who had been excited by the acquisition of Thompson. None of this was Spencer’s fault, but he became a lame duck first baseman that spring. In May, the Yankees alleviated the situation by trading Spencer for good, sending him and left-hander Tom Underwood to Oakland for first baseman Dave Revering.

The latter deal thrust Spencer into Yankee oblivion. He struggled in two seasons with the A’s before opting for retirement. I hardly ever heard his name mentioned again for roughly 20 years, even though he put in some time as a college coach at Navy and as Yankee scout. In 2002, I saw a small newspaper story noting that Spencer had died suddenly, succumbing to a heart attack while on a trip to participate in a charity baseball game. He was only 54. His passing created little fanfare, even with those who grew up with the Yankees during the “Bronx Zoo” years.

Sadly, few have remembered Spencer as part of the Yankees’ late 1970s run of pennants and World Series appearances. Like other similar role players of that time period, players like Jay Johnstone and Gary Thomasson, Spencer has become a forgotten figure in Yankee history. I guess that’s the fate that befalls old platoon players or bench performers; the more time that goes by, the less and less they seem to be pertinent.

Was Jim Spencer a great Yankee, a frontline star? Of course not. Was he a good role player on some good teams? I would say yes. He was a more-than-decent player who happened to play for two memorable Yankee teams, sandwiched around a very good individual season for a team that fell out of contention.

In an age when platoon players have become baseball’s version of the dinosaur, Jim Spencer deserves to be remembered a little bit better.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

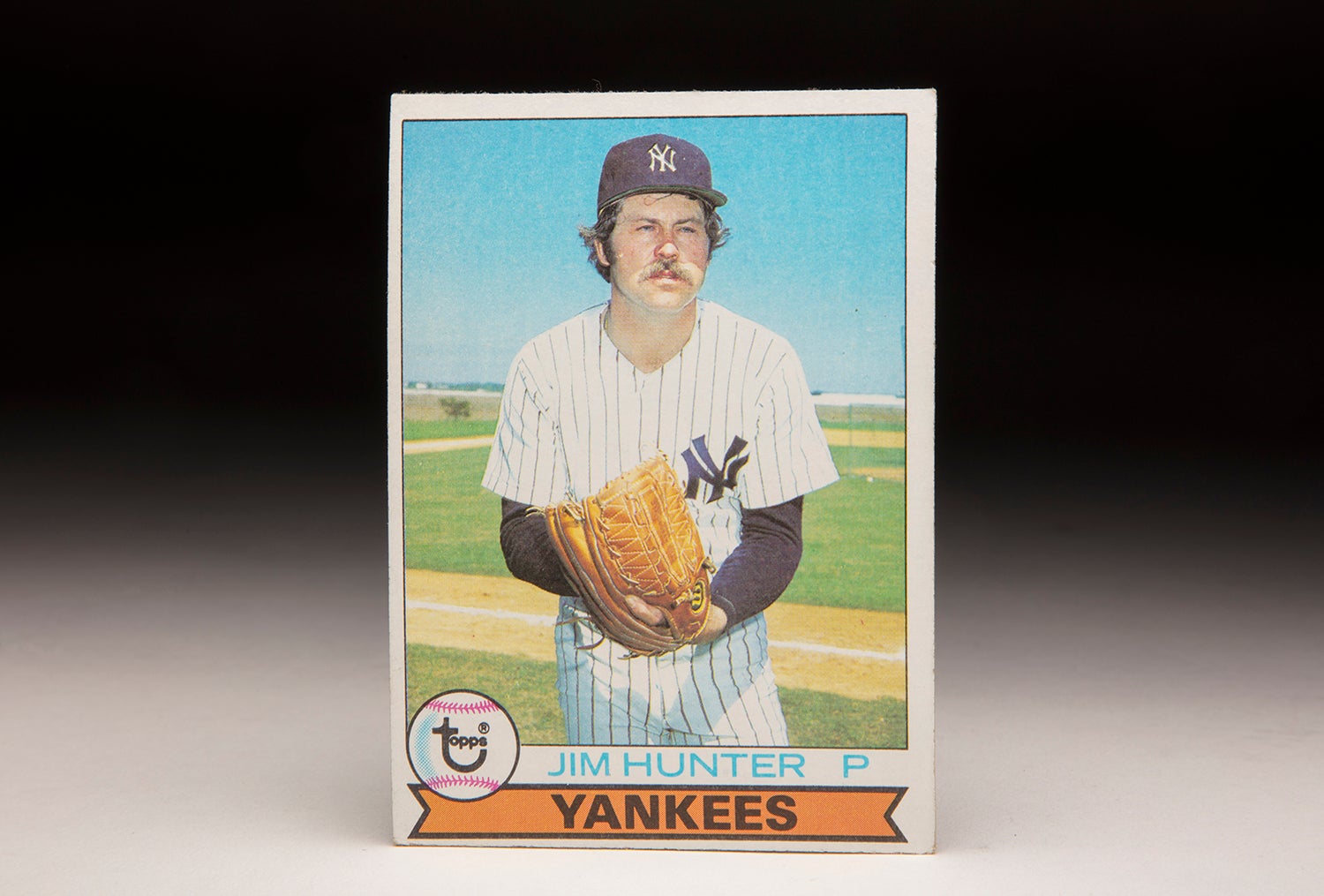

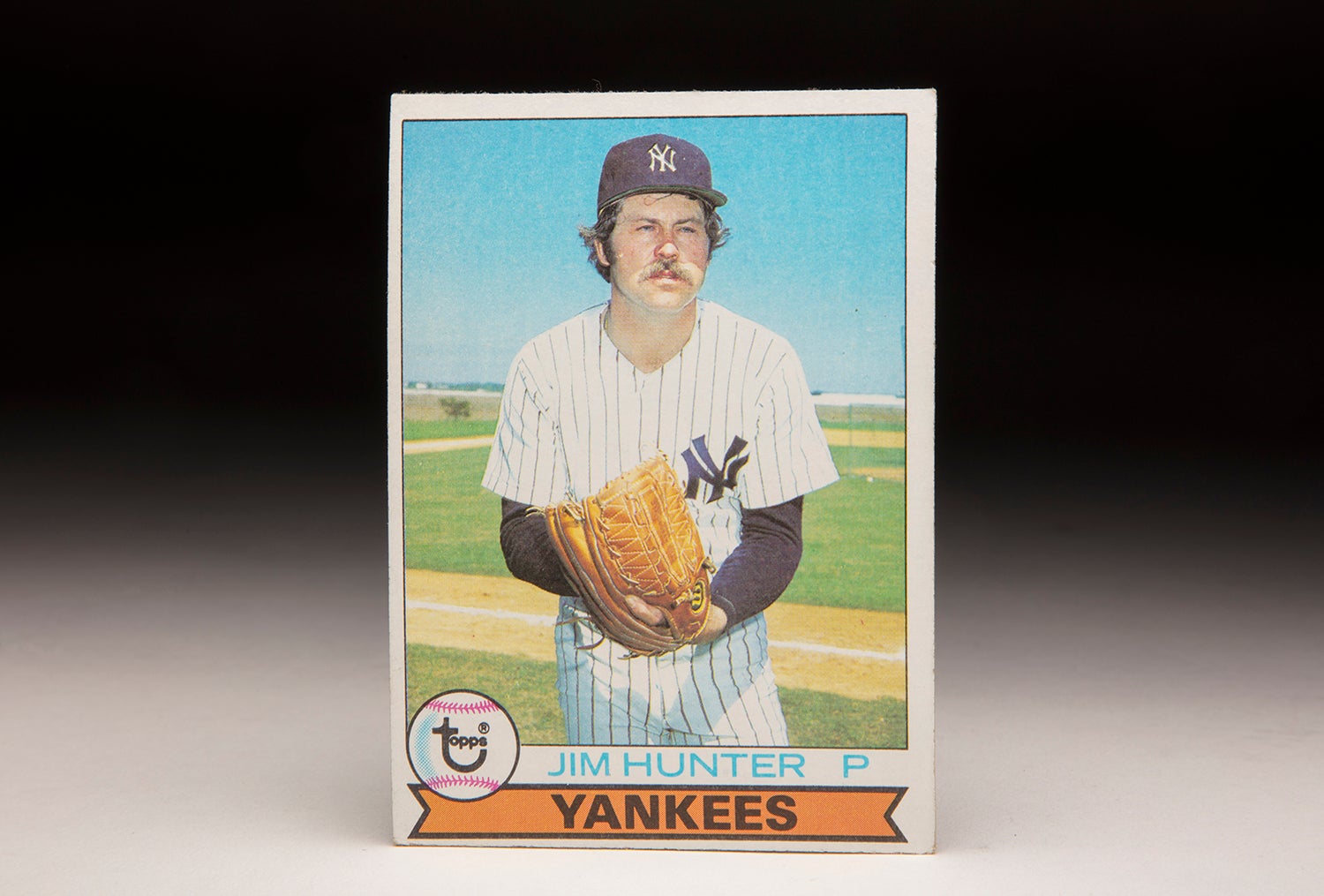

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Hunter

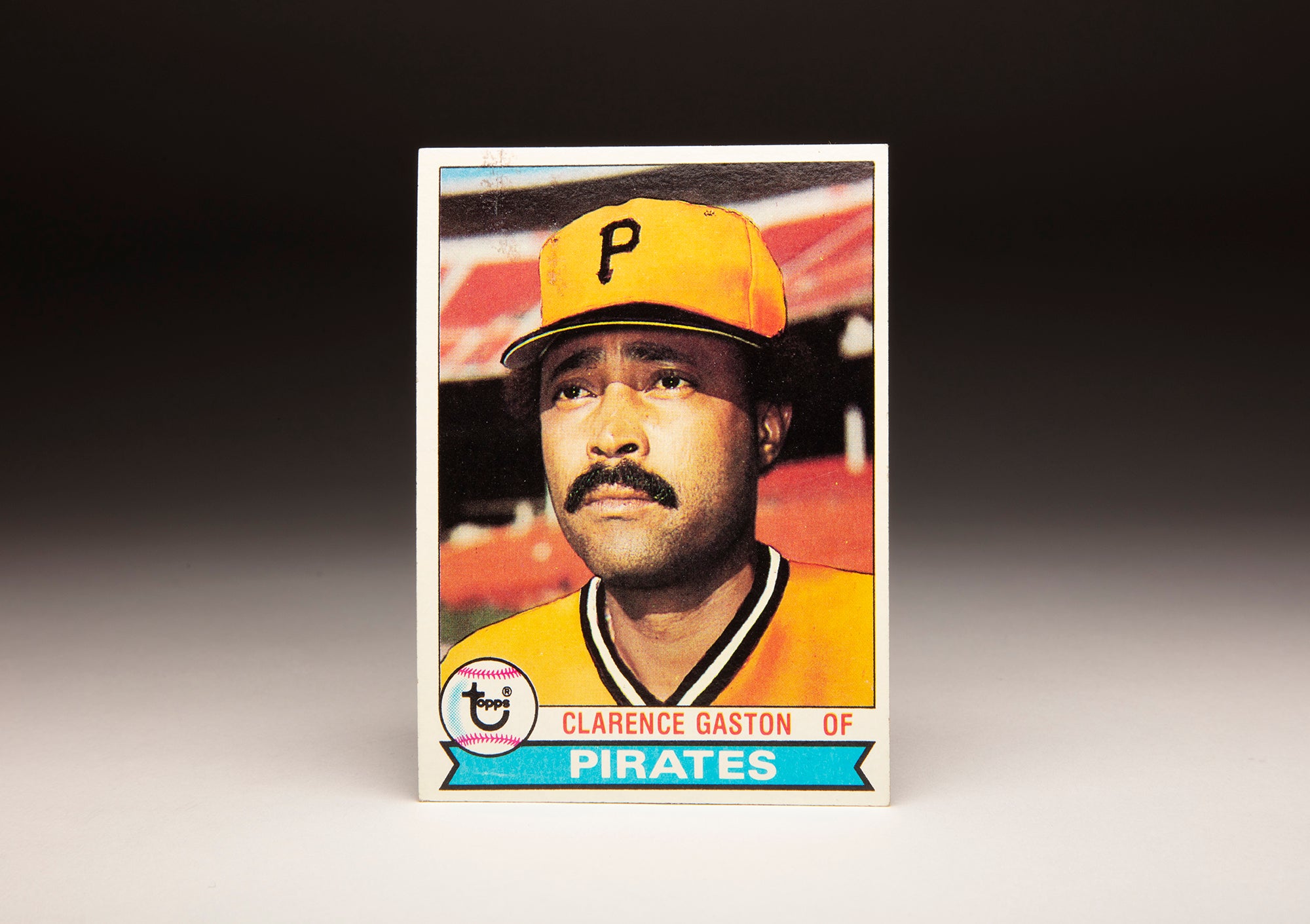

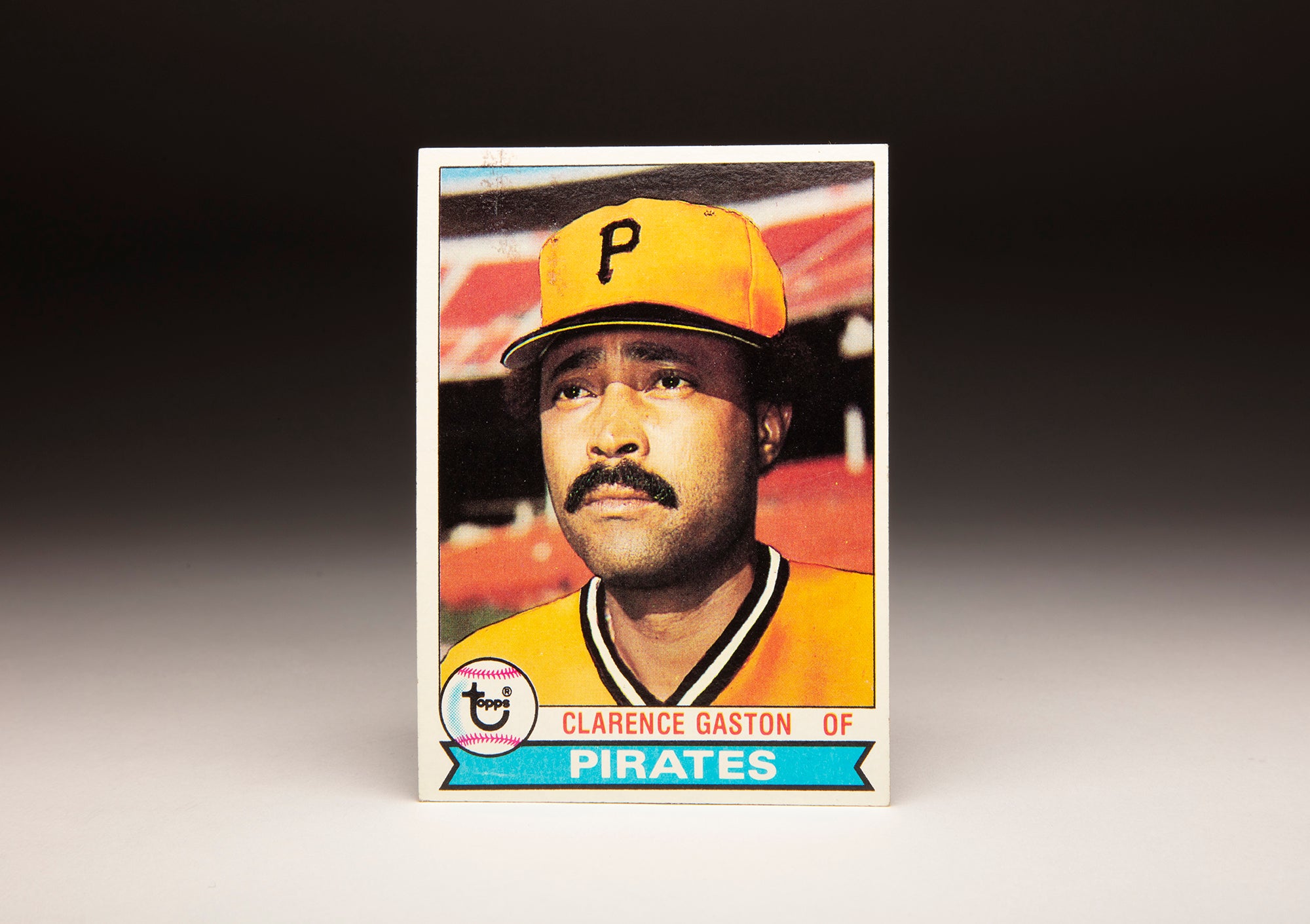

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Hunter