#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Melido Perez

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Sometimes readers of this feature ask me how I determine which cards should be profiled in Card Corner. That’s easy enough to answer.

First, the value of the card has almost nothing to do with the selection; for me, common cards can be just as intriguing as highly valuable cards. No, the choice has to do with other factors. Is the player colorful or controversial, or otherwise noteworthy? Does the card have a good design? Is the photograph well done, or is there something unusual about the card? If the answers to most of these questions are yes, then the chances are decent that the card will be profiled here at some point.

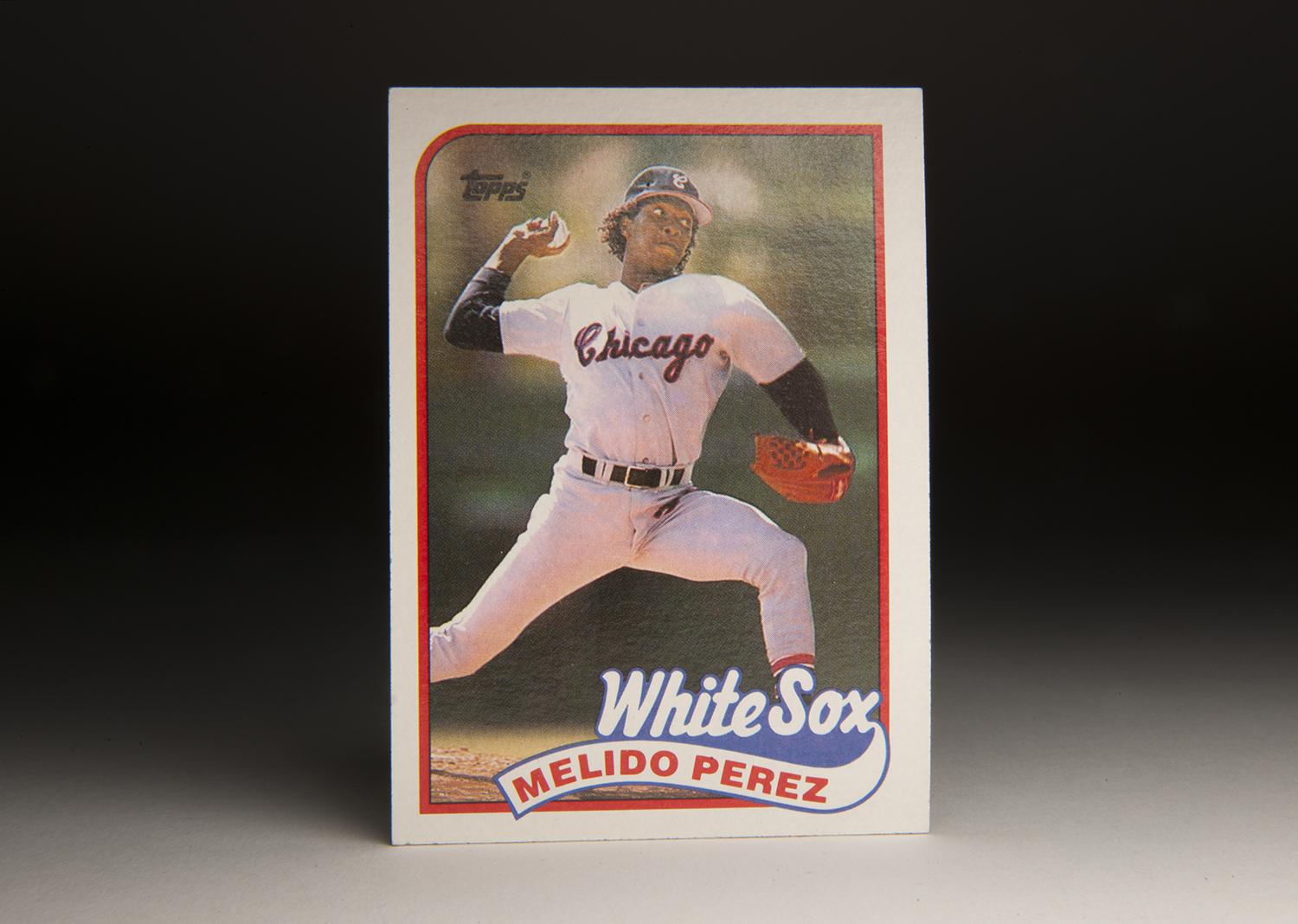

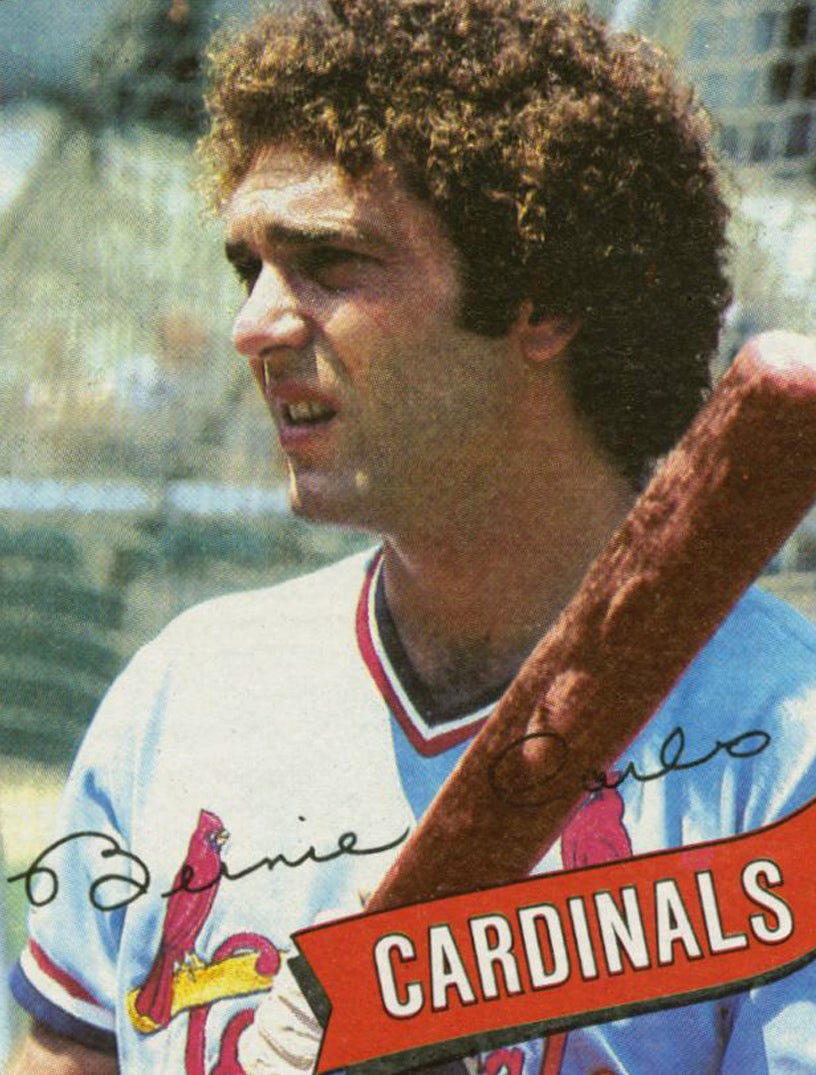

In the case of Melido Perez’s 1989 Topps card, it is one of my favorite cards in this set. First off, the 1989 set, along with the 1980, ’83, and ’87 editions, is one of Topps’ better offerings of the decade. The design has both substance and simplicity, while also giving the cards a bit of a three-dimensional punch, particularly in the way that the team name in bold script pops off the cardboard. I also like the counterbalance between the script team name and the player’s name in print. The photography throughout the set is very good, with clear, well-focused shots and a nice mix of action photography and posed portraits. There are no grainy, unfocused photos to be found here, as we sometimes see in earlier editions of Topps.

In taking this photograph of Perez, the Topps cameraman has done excellent work in capturing his pitching motion in mid-stride. Perez used a straight, over-the-top delivery, with sound mechanics. We can see those mechanics at work here, his athletic frame fully evident, his front leg driving forward, and his right arm near his ear. We can also see the intensity on Perez’s face; for him, it is obvious that pitching a baseball toward the batter is serious business.

The card also gives us a nostalgic look at the White Sox’ road uniforms from the late 1980s. I liked the Sox’s uniform design of that era; their jerseys were simple but attractive, highlighted by the word “Chicago” in scripted letters on the road grays, and “White Sox” on the home whites. Basic, unassuming, and dignified, those uniforms reminded me of a simpler time in baseball history.

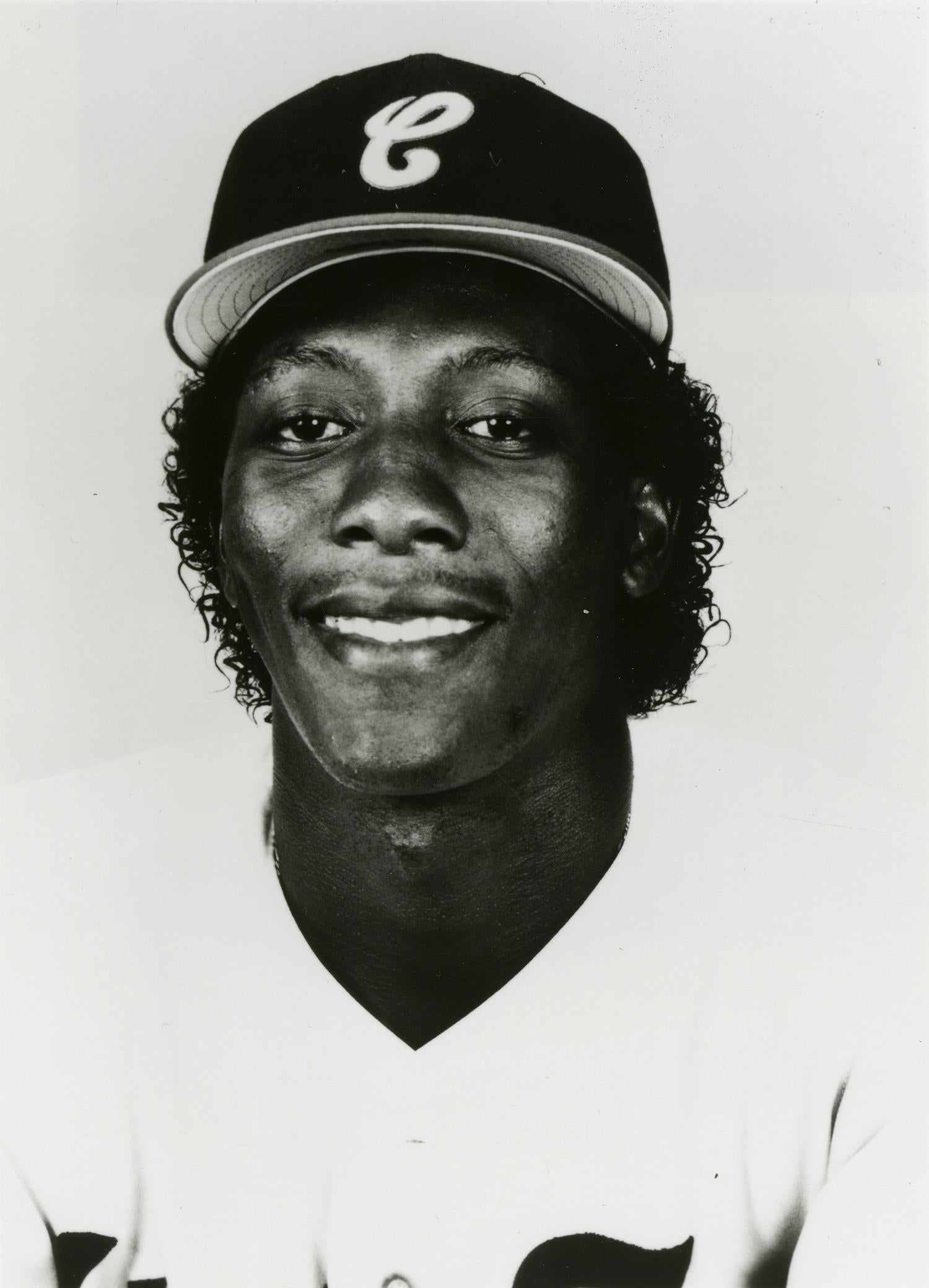

Sadly, the featured player on this card has become somewhat forgotten by time. Part of an intriguing baseball family, Melido Perez was one of three brothers to make the major leagues, along with Carlos Perez and Pascual Perez. (Three other brothers made the minor leagues, making for a total of six professional pitchers in the family.) Melido was almost always overshadowed by Pascual, a wild and wacky right-hander who once famously became lost driving his car to Atlanta Fulton County Stadium. On a more serious note, Pascual had a substantial problem with drug abuse, leading to his suspension from Major League Baseball in 1992.

Just when Melido began to establish his own name, he saw a promising career shortened by arm problems, ending his MLB tenure by his 29th birthday. Instead of becoming an integral part of the Yankee dynasty that would ensue in the late 1990s, Melido was already in retirement, cast aside by a fan base that didn’t want to remember past players from a difficult time in the team’s history.

This was Melido Perez’ second Topps card; his rookie card came out as part of the Topps Traded set in 1988. That one is similar to the 1989 card, just taken at a different stage in the pitcher’s delivery. Both cards show him with the White Sox, his second major league team. His professional career actually began with the Kansas City Royals, who signed him out of the Dominican Republic in 1983.

Melido had grown up in abject poverty, living in an overcrowded house. He and his eight siblings had to wear tennis shoes riddled with holes. On some days, they had nothing to eat.

Four years after the Royals made a dream come true, Melido made his major league debut. He struggled badly in three starts for Kansas City, but still showcased enormous talent with his live, right arm and his mid-90s fastball.

After the 1987 season, the Royals saw a chance to acquire Chicago White Sox ace Floyd Bannister, a capable left-handed pitcher. As part of the deal, they agreed to surrender four minor league prospects, Perez included.

Needing a starting pitcher right away, the Sox inserted Perez into their rotation, where he joined fellow rookie Jack McDowell and veterans Jerry Reuss and Dave LaPoint. Despite his rookie status, Perez more than held up. With his long, lean build, plus fastball, and terrific forkball, Perez opened the eyes of scouts and managers.

After winning his first three decisions, Perez was asked if he was surprised by his early success. “Surprised? No,” Melido told USA Today flatly. “When I come here, I have worked hard and I already have everything – the five pitches, the fitness, the time I put in winter ball.”

Perez had good reason for such confidence. By September, some scouts were calling Perez the ace of the White Sox’ staff. After the season, American League beat writers placed him sixth in the Rookie of the Year balloting.

Like many rookies, Perez struggled in his second full season. A sophomore slump saw his ERA rise to 5.01. Part of the problem stemmed from an increase in his walks. At one point, the Sox brought in former big league right-hander Orlando Pena, a forkball specialist, to work with him on his trademark pitch. Pena convinced Perez to throw the forkball with less velocity. The adjustment helped Perez show some improvement during the second half of the season.

All in all, the White Sox retained their belief in the young right-hander. In 1990, they made Perez their Opening Day starter. He would pitch much better in 1990, culminating in his performance against the New York Yankees on July 12. Perez no-hit the Yankees over six innings, the game shortened by a heavy downpour of rain. According to the rules of the day, Perez received full credit for the no-hitter. But Major League Baseball changed its statistical rules the following season, determining that a pitcher had to complete at least nine innings to receive no-hitter credit.

In 1990, Perez lowered his ERA by half a run and increased his win total to 13. Those numbers should have kept him a place in the rotation in 1991, but the White Sox had so much young pitching that they moved Perez to a bullpen role for most of that summer. Perez pitched well in relief, but the role seemed like somewhat of a waste of his talents. So that winter, the White Sox began shopping their talented forkballer.

In the meantime, the Yankees, coming off a horrid 1991 season, needed starting pitching in the worst way. They also needed an ace, and believed that Perez could fill that role. In January of 1992, the Yankees struck a deal, sending veteran second baseman Steve Sax to the White Sox for a package of three young right-handers: Bob Wickman, Domingo Jean, and Perez. Some Yankees veterans expressed frustration with the deal, particularly the loss of a .304 hitter like Sax, but the Yankees liked Perez too much to say no to the trade.

The trade happily reunited Melido with his brother Pascual, whom the Yankees had signed as a free agent two years earlier. The two brothers featured personalities that could not have reached more polar extremes. “They’re a good contrast,” reliever Steve Farr told the New York Times. “Melido doesn’t say two words. When you look at him, you’re seeing the other side of what Pascual could be.” Pascual, loud and outgoing, liked to joke with teammates and play pranks in the clubhouse.

Pascual wore his hair in a Jeri curl, while Melido preferred a close-cropped, old-fashioned haircut. Pascual enjoyed wearing garish jumpsuits, while Melido took a more conservative approach to fashion: Sport shirts and designer jeans.

The two brothers also found themselves at disparate points of their careers. The 34-year-old Pascual, who had at one time been a high-end pitcher in Atlanta, was now near the end. At 26, Melido was on the verge of tapping into his enormous talent.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Yankees wasted little time in making Melido a featured part of their rotation. He pitched brilliantly in 1992, spinning an ERA of 2.87. That he won only 13 games was not his own fault; that was the by-product of a sub-.500 Yankee team that struggled to score runs. Without question, Perez emerged as the ace of the Yankee staff, far and above the team’s other, older starting pitchers.

Unfortunately, the season did extract a toll on Perez’ arm. He threw 243 innings, by far the highest total of his career. He also threw a ton of forkballs, a pitch that has long been known for its taxing effect on the arm.

Perez would never be the same. The Yankees made him their Opening Day starter in 1993, but his arm bothered him, limiting him to 25 starts and vaulting his ERA above 5.00. He pitched a little better in 1994, but arm and back woes limited him to 22 starts. Frankly, the snap to his pitches was gone, never again to be seen.

In 1995, Perez reached rock bottom. He made only 12 starts, mostly ineffective ones. His ERA rose to 5.58. The Yankees discovered a tear in his pitching elbow, effectively ending his season. Too many forkballs had ruined his arm. “The last two years my arm was bothering me,” Perez admitted to Tom Keegan of the New York Post during the spring of 1996. “My arm was weak.”

No one could have known that the 1995 season would mark Perez’ final campaign as a big league pitcher. The Yankees used Perez as a minor league pitcher in 1996, but he never returned to the major league roster that season. They then allowed Perez’ $4 million annual contract to expire, making him a free agent. No one signed him in 1997, but the Cleveland Indians did offer him a Spring Training invite in 1998. The Indians needed pitching, but didn’t see enough to include Perez on the 25-man Opening Day roster. They offered him a minor league contract, but Melido opted for retirement, calling it a career at the age of 32.

The timing could not have been worse for Perez. He had suffered through some of the Yankees’ difficult rebuilding seasons – in particular 1992 and ’93 – and just when the Yankees started to become a contending team, he was no longer able to pitch. Sidelined for the 1995 Postseason because of injury, he missed out completely on the 1996 season, when the Yankees won their first world championship since 1978. With better luck and health, he could have been a part of the World Series seasons of 1998 and ’99, too, but it just wasn’t to be.

In the years since then, tragedy has struck the Perez family. After his retirement, Pascual Perez became seriously ill with kidney disease. While he was resting at his home in 2012, robbers staged a home invasion. Their motivation in ransacking the house was stealing Perez’ pension check, but an altercation ensued, with the assailants stabbing Pascual in the neck and head. The wounds proved fatal. Pascual was only 55.

In contrast to the tragic fate of his brother, Melido has enjoyed more prosperous times since his retirement. Always the rock among his siblings, Melido has found success in government. He is currently the mayor of San Gregorio de Nigua, a small city of 40,000 residents in the Dominican Republic.

It’s a remarkable story of success for a man who had grown up in such poverty, in cramped conditions with little money for food or clothing. Those days are long behind him, but now he is motivated by a desire to end the crimes that took the life of his brother Pascual, who died in San Gregorio de Nigua. “It is horrible what is happening in this country,” Melido said of the murderous attack on his brother. “You’re not even safe at home.”

Here’s hoping that Melido Perez, who tasted baseball success briefly before hurting his arm, will make another name for himself in service of his native land.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame