- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Zoilo Versalles

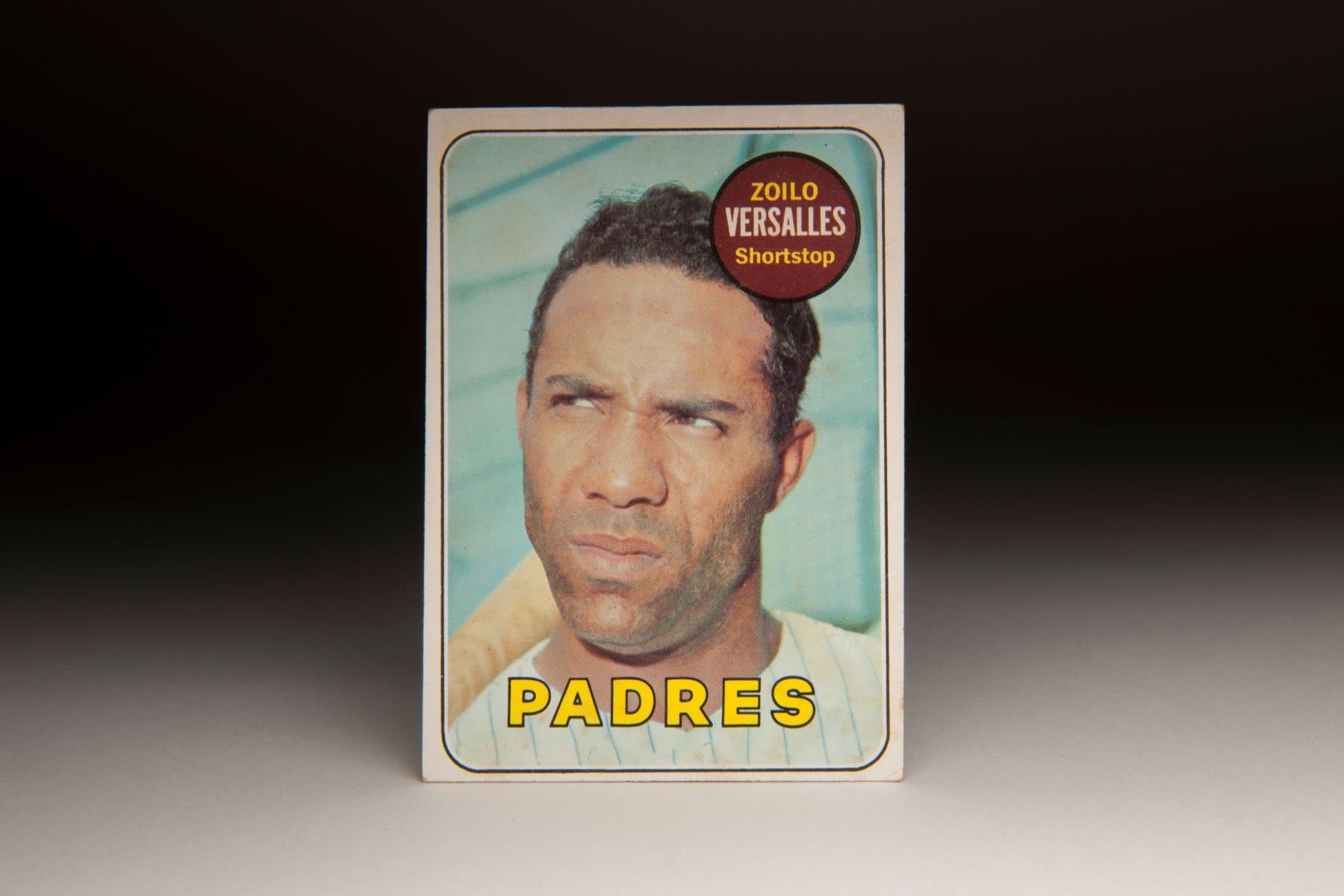

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Zoilo Versalles

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Zoilo Versalles does not look happy on his 1969 Topps card.

As he holds his bat on his right shoulder, he seems disgusted that he has to pose for yet another card photograph, or maybe he is irritated by something that he sees off to the side. After all, his eyes are shifted well to his right; he is not even looking directly into the camera at the moment the picture is taken.

Additionally, Versalles appears old and worn down in this photograph, which was likely taken one or two years after his peak season of 1965. With the five o’clock shadow created by the beginnings of a beard, and with his hair starting to show flecks of gray, Versalles looks older than he should. I’m guessing that he was about 27 when this photo was taken, but he appears about 10 years older, well into his late 30s.

Now it could be argued that the Topps photographer simply caught Versalles at a bad moment, when he was irritated, distracted, and unable to tidy up for his picture. That has been known to happen; just ask the Topps photographer who took Billy Martin’s picture for the 1972 set. Or just ask photographer extraordinaire Doug McWilliams, who occasionally heard a player swear at him when he introduced himself as a representative of Topps!

Or could there be something more going on here? By the late 1960s, Versalles’ career was tracking downward. Within a span of a few seasons, his status had fallen from superstar to that of a utility infielder. He was also struggling with some personal demons that would not become known until many years later.

Born in Cuba, Versalles was one of the last players to leave the island prior to the reign of Fidel Castro and the ending of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States. Emerging from poverty in one of the worst sections of Havana, Versalles became a star at the amateur level. He was exceedingly skinny – scrawny might have been the best description – but he could hit, even at an early age. He played parts of two seasons in the Cuban Winter League, drawing attention from the Washington Senators and their legendary scout, Joe Cambria. “Papa Joe” had already developed a pipeline of talent from Cuba to Washington, and that continued with his signing of Versalles.

Attending his first Spring Training camp in Orlando, Fla., in 1958, Versalles found life unsettling in the United States. He struggled with the language, had difficulty communicating with his teammates, and felt homesick being separated from his family and his girlfriend. The feelings of homesickness persisted for years, sending him into repeated depressions.

Language and cultural barriers led to an early misunderstanding. Many of his teammates, either unable to properly pronounce his name or simply making him the victim of clubhouse pranks, started calling him “Zorro.” Versalles didn’t particularly like the nickname, even though his teammates meant it in an affectionate way, as they made the connection to popular television character of the same name. Due to his limitations with English, Versalles said little to his American teammates in those early years. He developed a reputation among media members for being moody and reclusive, an unfair labeling given the difficulties he faced in adjusting to stateside life.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

After only a season and a half of minor league apprenticeship, which had gone no higher than Class B ball, Versalles was rushed to the big leagues by the Senators in 1959. He was all of 19, and it was no surprise that he felt overmatched at the plate, where he batted .153 in 59 at-bats. Clearly not ready, Versalles went to Triple-A Charleston in 1960. There he performed admirably, putting up respectable offensive numbers. Again, the Senators called him up late in the season, but he once again struggled, batting just .133.

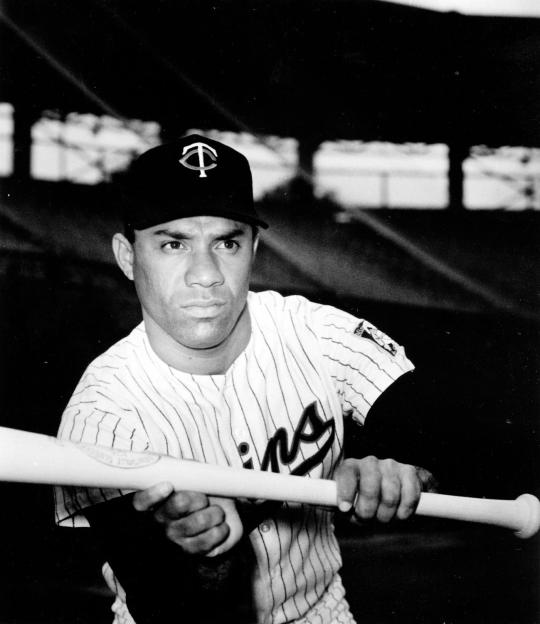

When the 1960 season came to a close, the Senators moved out of Washington and relocated to the Twin Cities, where they became reborn as the Minnesota Twins. Making the move with the franchise, Versalles played well during Spring Training and earned the Opening Day nod at shortstop for the Twins. Now Versalles showed himself ready. He batted .280 with seven home runs and 16 stolen bases, all the while playing a dandy shortstop. Still only 21, Versalles had arrived.

In 1962, Versalles saw his batting average fall off by nearly 40 points, but he increased his power substantially. He was all of 5-foot-9 and 145 pounds, but he more than doubled his home run total, hitting 17 long balls. His defensive play, already impressive, advanced further. American League beat writers took notice, giving Versalles some back-of-the-ballot support in the Most Valuable Player Award voting.

Versalles played well despite persistent feelings of being homesick. Isolated from his fiancée and his family, Versalles actually left the Twins at one point that season, before quickly changing his mind and returning to the club.

Over the next two seasons, Versalles shined. He hit a combined 30 home runs, led the league in triples both years and earned his first All-Star Game appearance in 1963. He also won the Gold Glove Award that season, despite committing 29 errors; Versalles had incredible range to either side of the ball and a penchant for the spectacular play. Along with Luis Aparicio of the Baltimore Orioles and Jim Fregosi of the Los Angeles Angels, Versalles was one of the three best all-round shortstops in the American League.

In 1965, Versalles vaulted to No. 1 on the list. But the season did not start well. During Spring Training, he played a bad game against the New York Mets. Twins manager Sam Mele accused Versalles of “not trying.” The shortstop did not take it well, claiming his preference for Twins third base coach Billy Martin over Mele. “I play for Martin, but I no play for you.”

By midseason, those words became forgotten. Not only did Versalles earn his second All-Star appearance, but he also won his second Gold Glove Award and exploded as an offensive force while batting out of the leadoff spot. Versalles led the league in doubles, triples, total bases, and runs scored. He also hit 19 home runs and stole 27 bases. Given the context of baseball at the time, a sport dominated by pitching over hitting, Versalles’ numbers become even more impressive. That he did all of this as a shortstop, a position known for fielding, made him stand out as the American League’s top player. The writers voted him Most Valuable Player.

In retrospect, critics have questioned whether Versalles should have won the award. Some have contended the award should have gone to his Twins teammate, fellow Cuban Tony Oliva, who won the American League batting title. But at the time, there seemed little doubt among the writers. Versalles received 19 out of 20 first place votes, more than establishing a consensus among the writers who covered the league on a regular basis.

Even on the stage of the World Series, with its enormous pressure on all participants, Versalles continued to excel. He hit .286, ripped a home run, and posted an OPS of .833. It was certainly no fault of Versalles that the Twins lost the Series in seven tough games, falling to the Los Angeles Dodgers of Sandy Koufax/Don Drysdale vintage.

Showing humility throughout his career season, Versalles offered credit to Martin, the Twins coach who had helped him develop into a star. “Billy understands. He used to be an infielder, so he knows what he’s talking about,” Zoilo told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “He talk to me in a nice way. He doesn’t jump all over a fellow like some coaches do on other clubs.”

Off the field, Versalles showed growth, too. No longer shy about speaking English, he became more outgoing with his teammates. At one time a poor youth growing up in Cuba, he was now cultured with upper class tastes. A lover of opera, he often sang in the clubhouse showers, which may or may not have delighted his teammates. He was also an accomplished cook and often hosted pig roasts at his Minneapolis home for friends from Cuba.

With Martin on his side, and youth in his favor, there was no reason to believe that the 25-year-old Versalles would not continue to star for several more seasons. Unfortunately, the demons that Versalles battled would take a toll. Still not comfortable in American culture, Versalles struggled with panic attacks and nervousness. He also suffered physical ailments. He came down with a bad case of the flu in the spring of 1966, weakening him for the first two months of the regular season. A blood clot in his right shoulder also bothered him in ‘66, forcing him to miss 12 days. That summer, he batted only .249, saw his home run total fall to seven, and slipped defensively, too.

Versalles’ play only worsened in 1967, in part because he injured his throwing shoulder in the spring. He also suffered back pain, a continuing problem that stemmed from his 1966 blood clot. His batting average sank to an even .200, and his OPS declined to .530. Just like that, so suddenly and without much warning, Versalles was no longer an elite player.

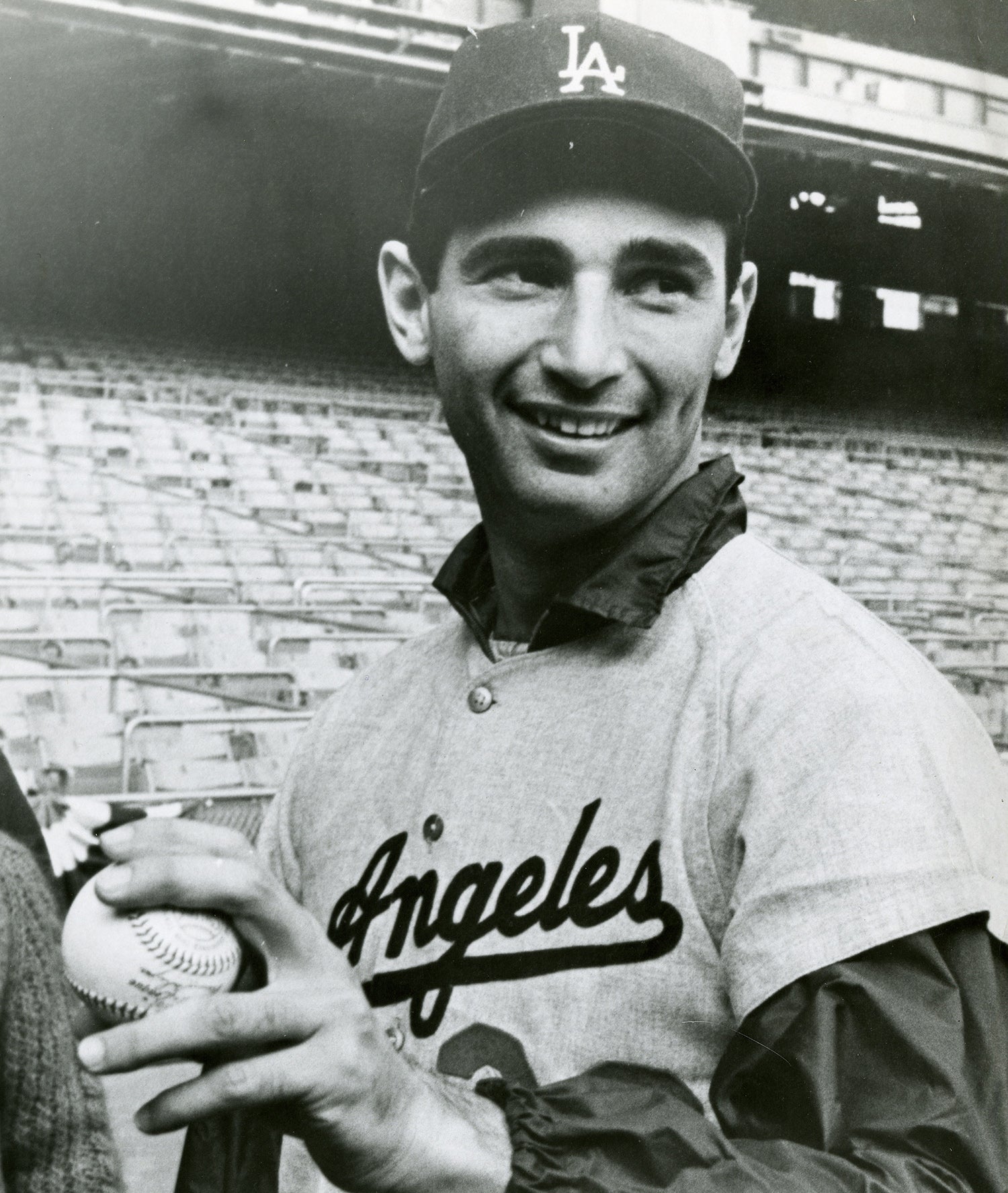

The Twins were so startled by Versalles’ collapse that they entertained trade offers that winter. Believing that young Jackie Hernandez could handle shortstop for them, the Twins decided to make a move in November, sending Versalles and veteran right-hander Mudcat Grant to the Dodgers for a package of veteran catcher Johnny Roseboro and relief pitchers Ron Perrranoski and Bob Miller. Versalles, long a fan of the Dodgers, was thrilled.

Remembering what they had seen of Versalles in the 1965 World Series, the Dodgers made him their starting shortstop. After all, he was still only 28 years old and might have benefited from playing for an organization that historically had treated minority players well. The change of scenery, which Versalles had reacted to with glee, did not help. Versalles batted .196.

To make matters worse that season, Versalles stumbled over a base awkwardly, hurting his back. Years later, Versalles remembered the injury in an interview with sportswriter Bill Madden, who was working for the Sporting News at the time. “I tripped over the bag, did a somersault,” Versalles told Madden. “The next day, I couldn’t get out of bed. The pain started in my shoulder and went all the way to my back and leg.”

With his back compromised and his performance already subpar, Versalles became expendable. The Dodgers left him unprotected for the upcoming expansion draft. One of the four new teams, the San Diego Padres, selected Versalles. But Versalles never played a game in a Padres uniform. In December, the Padres sent him to the Cleveland Indians as the player to be named later in a trade for slugging minor league first baseman Bill Davis.

The Indians had a major need at shortstop, but they also had problems at third base. On Opening Day, the Indians started Versalles at the hot corner. He essentially became a high-profile utility player, appearing in games at third and second, and once in a great while at his original shortstop position. He hit only slightly better with the Indians and struggled even in bending down to handle easy ground balls. In late July, the Indians sold him to the Senators. The transaction brought him back to his original major league city, but with a different incarnation of the Senators. These were the expansion Senators, who had finished eighth or lower in the standings seven times during the 1960s.

Again playing as a utility infielder, Versalles hit a respectable .267, but with no power or speed, and showed no mobility in the field. After the 1969 season, the Senators arranged for him to have surgery on his back. The Senators brought him back for Spring Training in 1970, thinking that he could play second base every day. But his play was so unimpressive that Washington asked him to start the season at Triple-A Denver. Versalles refused the assignment, so the Senators released him before Opening Day.

No other team wanted Versalles. He still wanted to play, so he sought refuge in the Mexican League, where the pay was decent and the quality of baseball was somewhere between Double-A and Triple-A in the states. For the better part of the next two seasons, Versalles starred for a team called Union Laguna.

While playing in Mexico, Versalles called his good friend, Atlanta Braves first baseman Orlando Cepeda, asking him for help in getting back to the big leagues. Always loyal, Cepeda convinced his manager, Lum Harris, that the Braves should give Versalles a tryout. Not satisfied with Marty Perez at shortstop, the Braves decided to give Versalles a look and saw enough to offer him a contract. He would hit five home runs for the Braves, but otherwise struggled. A .191 batting average and diminished range in the field convinced Atlanta to release him that winter.

That move ended his major league career, but Versalles went back to the Mexican League in 1972. Late that season, he signed a contract with the Japanese Leagues, which generally paid more money than the Mexican League. Versalles’ stint in the Far East turned into a disaster. He hit so poorly that the Hiroshima Toyo Carp released him. From there, he signed a minor league contract with the Kansas City Royals, playing briefly in their system, before heading back to the Mexican League. By the end of 1974, Versalles was done, ready to call it quits at the age of 34.

Versalles wanted to continue his baseball career in some other capacity, preferably as a minor league coach. But no one within the game would offer him a job – not even Twins owner Calvin Griffith – at any level. Without a regular income, Versalles struggled to stave off poverty while living in Minneapolis. He plowed through a series of menial jobs, the only employment that he could find. Part of the problem involved his struggles with English; Versalles had never learned to read or write the language. Another problem concerned his chronically bad back, which prevented him from doing jobs that involved heavy physical labor.

By the 1980s, he felt he had no choice but to sell off all of his trophies, including his 1965 MVP Award. But it wasn’t just because of the need for money. He felt he no longer had a connection to the trophies because they had been given to him by people within the game who now refused to provide him employment. Feeling bitter, Versalles rid himself of his MVP Award, his Gold Glove Awards, and his All-Star Game rings.

Even with the money coming in from those trophies, Versalles could not sustain himself. He lost his house to foreclosure. In his later years, he lived in a small home in suburban Bloomington. He lived there alone, separated from his wife and his six daughters. It was a sad existence for a man who had once been a star.

Versalles’ health also suffered. In the 1970s, he developed colitis. In 1984, he underwent major surgery to his colon. He would also suffer two heart attacks.

Sadly, Versalles’ medical plight made the news of June 2, 1995, less surprising. Versalles’ body was found in his Bloomington rental home. He had been dead for two days, gone at the age of 55. An autopsy later showed that Versalles had succumbed to arteriosclerotic heart disease.

It was a difficult end to a difficult life. Versalles’ story is one of those unfortunate reminders that even star athletes, players who seem to have everything in their favor, can lose their health, their family, and their money so quickly.

In this case, an innocuous baseball card from 1969 told us all too much about the heartbreaking fate of Zoilo Versalles.

Special thanks to Doug McWilliams and author Thomas Henninger for their assistance with this article.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

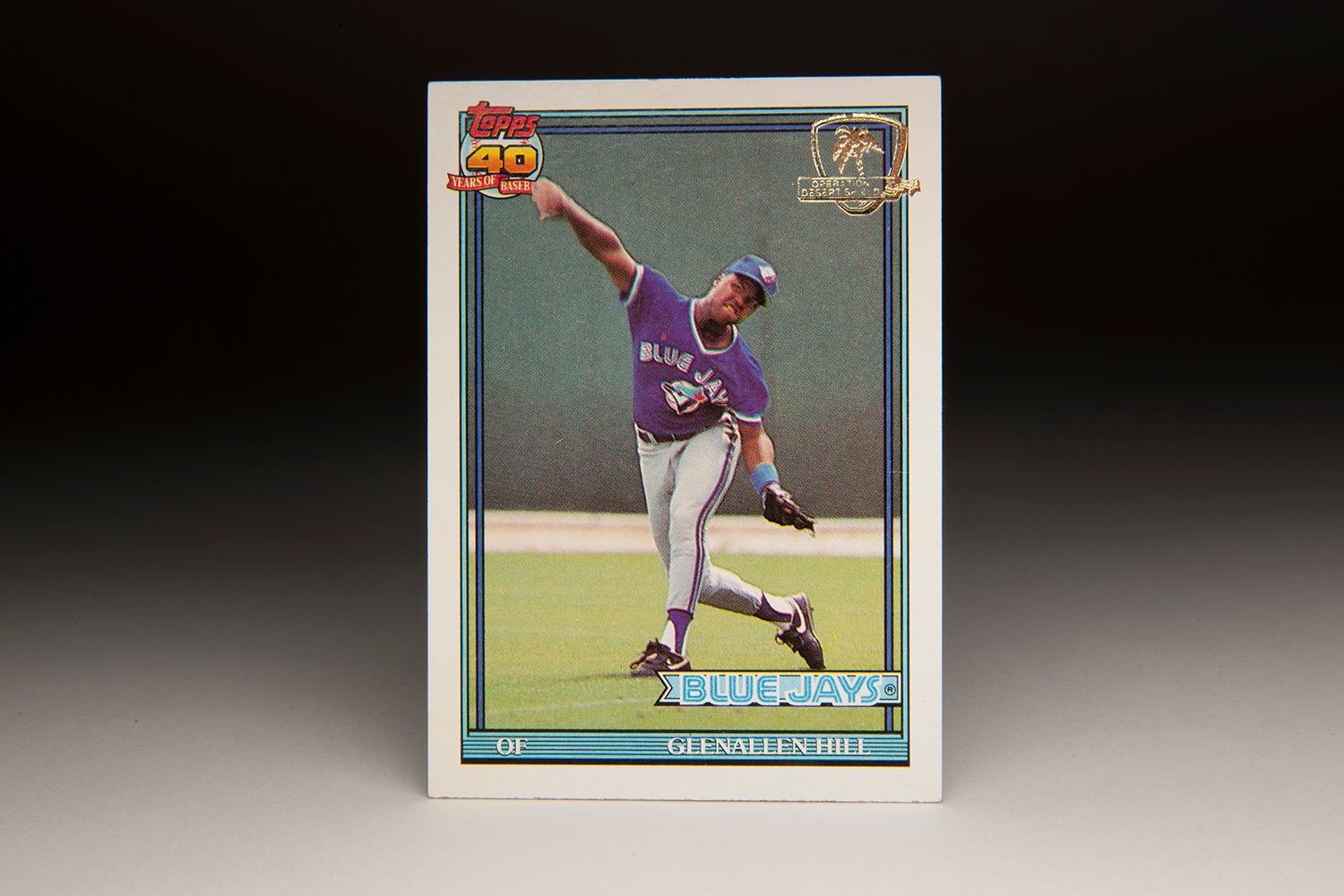

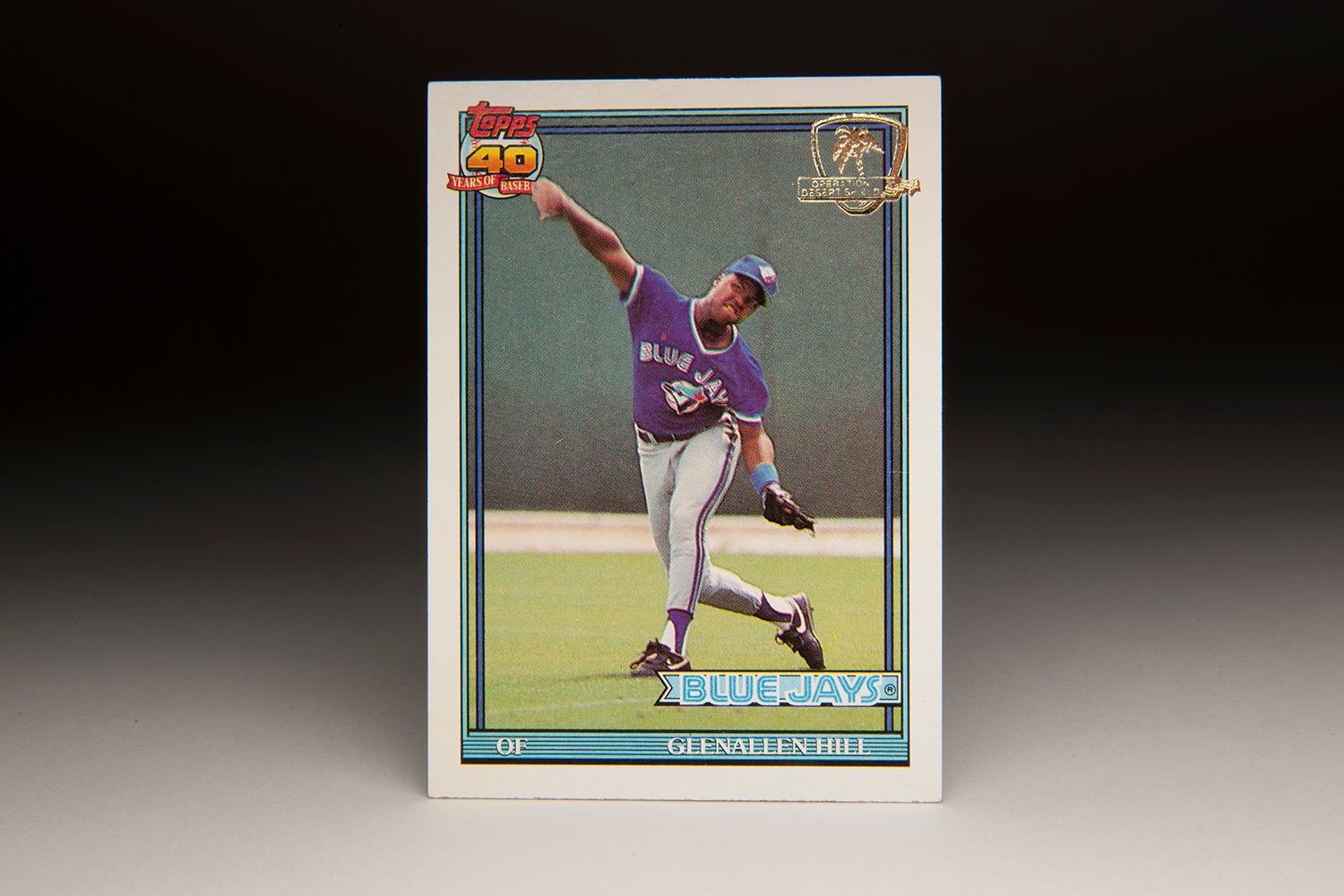

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Glenallen Hill

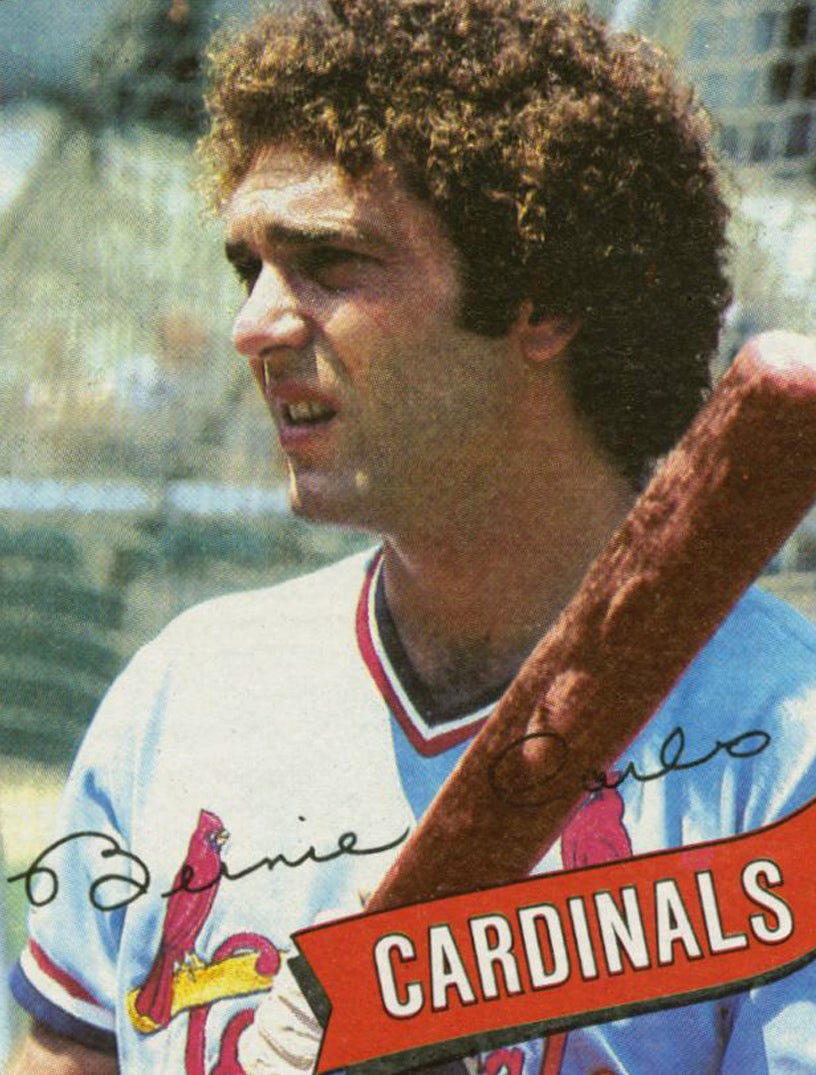

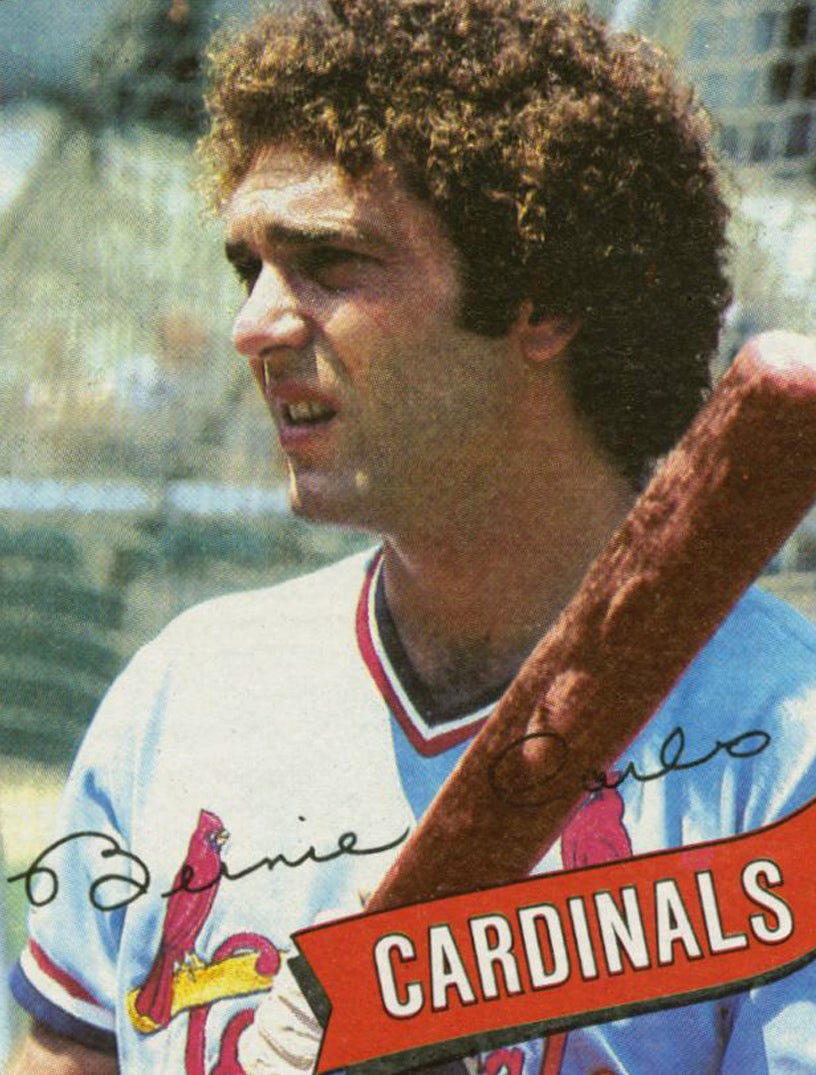

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

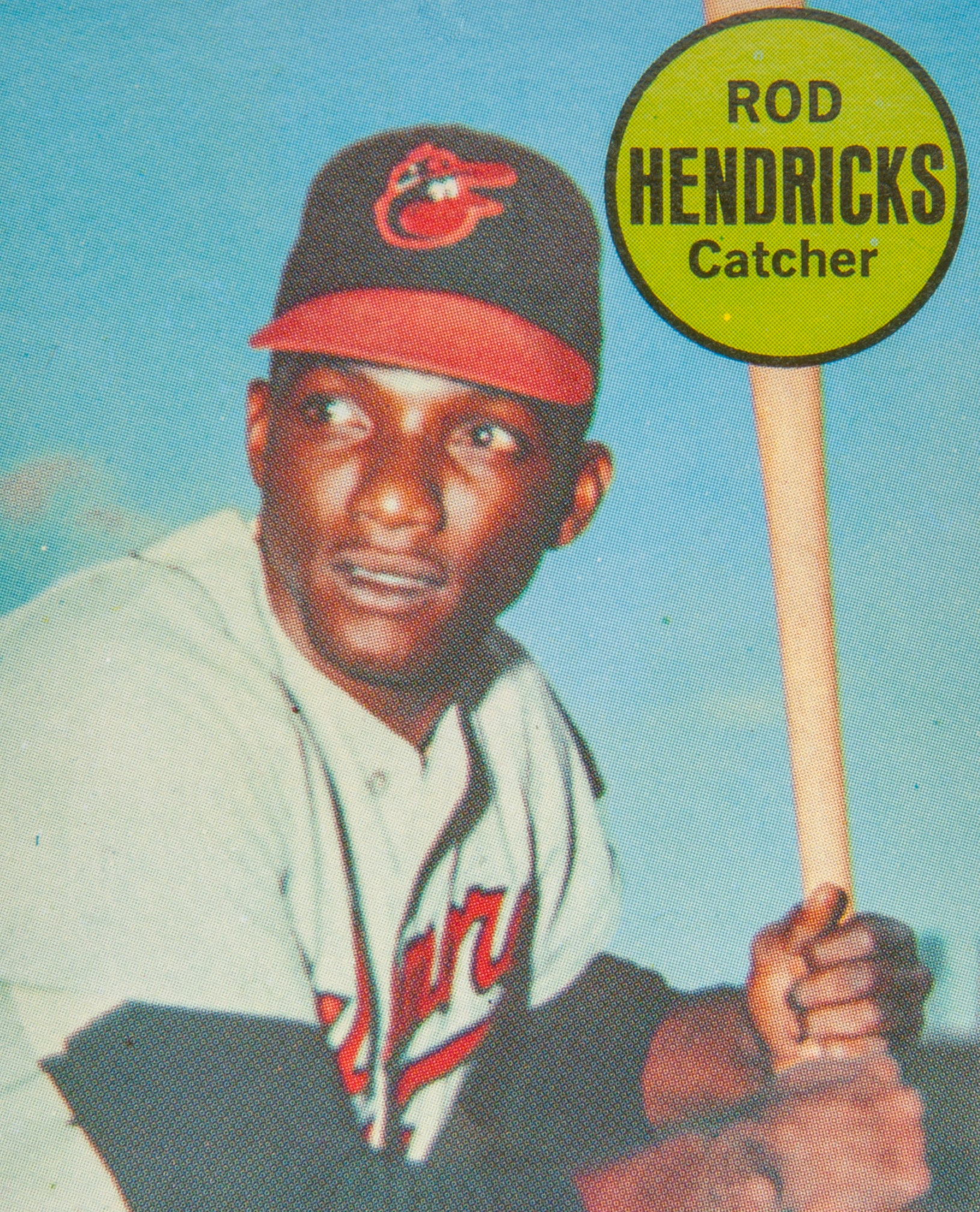

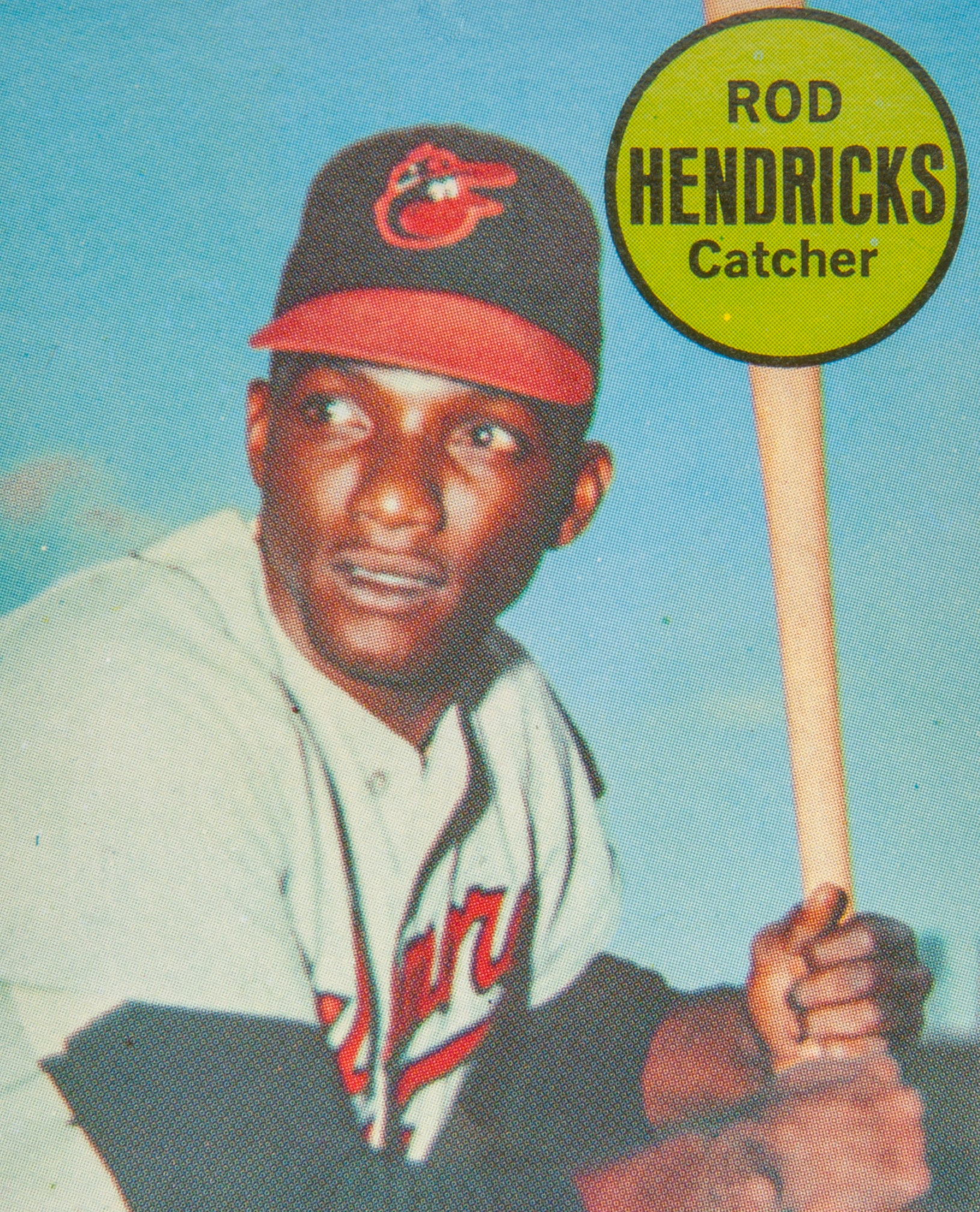

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Glenallen Hill

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

Related Stories

'On Account of War'

DICK ENBERG NAMED 2015 FORD C. FRICK AWARD WINNER FOR BROADCASTING EXCELLENCE

Spaceman Headlines 11th Annual Baseball Hall of Fame Film Festival Sept. 23-25 in Cooperstown

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

George Brett returns to get 3,000th hit

Cap Selections Announced for Craig Biggio, Pedro Martinez and John Smoltz

Pre-Integration Era Committee Ballot to Be Considered Dec. 7 at Baseball’s Winter Meetings

Symposium brings together baseball, academia

GOLDEN ERA COMMITTEE ANNOUNCES RESULTS

01.01.2023

Baseball Writers’ Association of America 2017 Hall of Fame Ballot Announced

01.01.2023