Photo Finish: Technology has transformed baseball photography in an instant

To appreciate just how far baseball photography — and photography in general — has come in the last 50 years, consider this: Until the conversion to digital cameras in the 1990s, even the most gifted photographers, who made documenting baseball history an art form, had no idea what might show up on the film they shot. Shooting masterful pictures was part skill, part mystery.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Doug McWilliams, legendary photographer for Topps Baseball cards, had to shrug his shoulders one morning in Spring Training in 1984 when he bumped into young San Diego Padres star and future Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn. They were about to shoot his second-year card.

“He said, ‘I hate my rookie card,’” McWilliams recalled. “And I said, ‘I don’t blame you.

I had no choice of what they chose.’”

With so many players to shoot that Spring Training in Arizona, McWilliams used to FedEx his film to New York every three days to be developed there. He wouldn’t know what images editors chose until the cards came out. McWilliams had sent a series of posed and action shots of Gwynn. The editors picked one of Gwynn running off first base, back end to the camera.

“He said, ‘All you see is my big rear end,’” McWilliams said. “I said, ‘I agree. I’m sorry.’”

One of those 1983 Gwynn rookie cards in gem mint condition has sold for $4,999 on eBay. McWilliams, now 86, has to chuckle.

Longtime Sports Illustrated baseball photographer Brad Mangin used to put film he shot from games in the Bay Area on a red-eye flight from San Francisco to the Newark Airport. He would toss and turn that night not knowing what the editors in New York would find developing the film while he was still asleep the next morning.

“If there’s a great action play at home plate, in the old days, you just never knew,” Mangin said. “You hope that you got it in focus. You hope your exposure is right. You hope everything’s right. But you have no way of knowing.”

One morning after shooting a series of Mariners games in Seattle, Mangin woke up to a call from editors saying the film he had sent had a white slit through it.

“One of the shutter blades had blown out,” Mangin said. “I wouldn’t have known because the film went through the camera.”

The editors knew there was nothing Mangin could have done. They just wanted him to know to stop using that camera.

Generally speaking, magazine photographers were among the last to make the switch to digital cameras. Newspaper photographers were quicker to reap the benefits of being able to see the images they’d captured in a small screen on the back of the camera. They could hit a delete button right then and there or on a laptop nearby once they downloaded pictures. It alleviated a lot of stress over whether or not they’d captured the moment they wanted.

Photographers jokingly started to call someone peeking at their small digital screens “chimping,” for the “oohs” and “ahhs” they made gawking at their own images. But it gave them the benefit of knowing if they were on the right track.

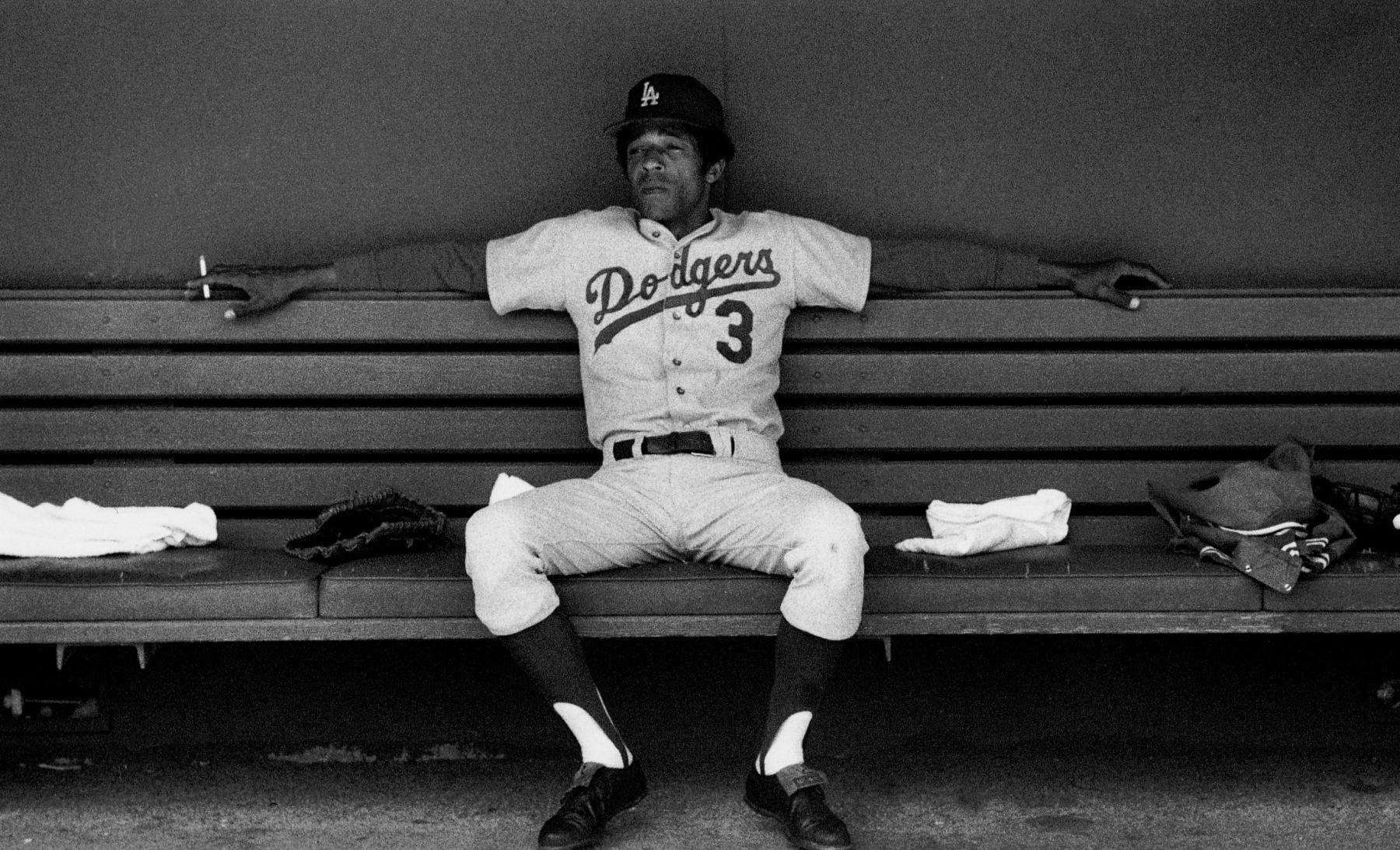

“When digital first came out, my first thought was, ‘Hell no, I’m not doing this. I’m a film guy,’” said Michael Zagaris, longtime team photographer for the Oakland A’s. “It takes about two years, and you figure out this is where it’s going. And in another year or so, if you’re not doing digital, you’re not working.”

Digital technology came as part of a series of improvements made to cameras, starting with the use of motor drives to advance the film, autofocus to sharpen the images and technology that made better use of light.

Shooting in color at night had rarely been an option with film photography. With digital cameras, photographers got to where they were comfortable shooting in color day or night and even off the field, where lighting is less predictable.

“There are things that you get digitally, you wouldn’t have gotten either at all or nothing like they look now in the clubhouse or night games,” said Zagaris, who built his reputation on capturing players in the dugout, clubhouse and stadium tunnels. “Now with digital cameras, there can be a power outage in the clubhouse. You could strike a match. I can take a picture of you, and it’ll look pretty good.”

Digital cameras are also faster. When motor drives were introduced in the late 1960s, photographers could shoot about three frames per second, Mangin said. By the 1980s, it was five frames per second. With digital cameras, it was more like 10 or 12 frames per second.

“The big thing now is mirrorless cameras,” Mangin said. “They get 30 frames a second, which is basically shooting a movie.”

Curtis Compton, a retired sports photographer for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, said faster cameras meant having a better chance to capture a game’s crucial moments, which is how he made his living shooting the Atlanta Braves. Faster cameras come in handy in an environment where balls are pitched at nearly 100 mph and hit even faster.

“You’ve got the bat exploding when it breaks, and the ball coming off of it,” Compton said. “If you’ve got 15 or 20 frames to pick from — or images — instead of three, you’re much more likely to have the ball coming into the catcher’s mitt and showing the runner beating the ball out, the helmet flying off, the actual impact. The moments are just much better. And the image quality is much better.”

Photographers like Compton, Zagaris, Mangin and McWilliams have been capturing impactful moments for years, regardless of the camera they were using. As McWilliams said: “It’s not the equipment that makes the picture, it’s the nut behind the viewfinder.”

Compton shot one of his favorite photos of his 29-year career in black-and-white in 1984. He captured Braves outfielder Claudell Washington punching umpire Lanny Harris on his way to the mound to take on Reds pitcher Mario Soto. Even video of the moment doesn’t show what Compton revealed in one still image: Washington’s outstretched left arm, hand clinched in a fist, and Harris recoiling.

In a way, getting images no other photographer gets has become that much more challenging with every photographer shooting digital. Mangin felt that pressure the night he shot Barry Bonds breaking Hank Aaron’s career home run record. To get a unique angle of No. 756 for a two-page spread in Sports Illustrated, he wound up outside AT&T Park, on his hands and knees, shooting through a chain link fence, next to some homeless people.

Perhaps most impactful of all has been what digital technology has done for the speed with which photographers can transmit their photos.

One black-and-white image used to take Compton nine minutes to send back to his newsroom, using something called a “drum transmitter” — assuming there was no static on the phone line forcing him to start over. The image would appear in the next morning’s paper. Now he can send images from a photo well through a high-speed line plugged into his camera and have it online in a matter of minutes.

What used to take Mangin hours to send on a red-eye flight to New York, he can do himself with the push of a button.

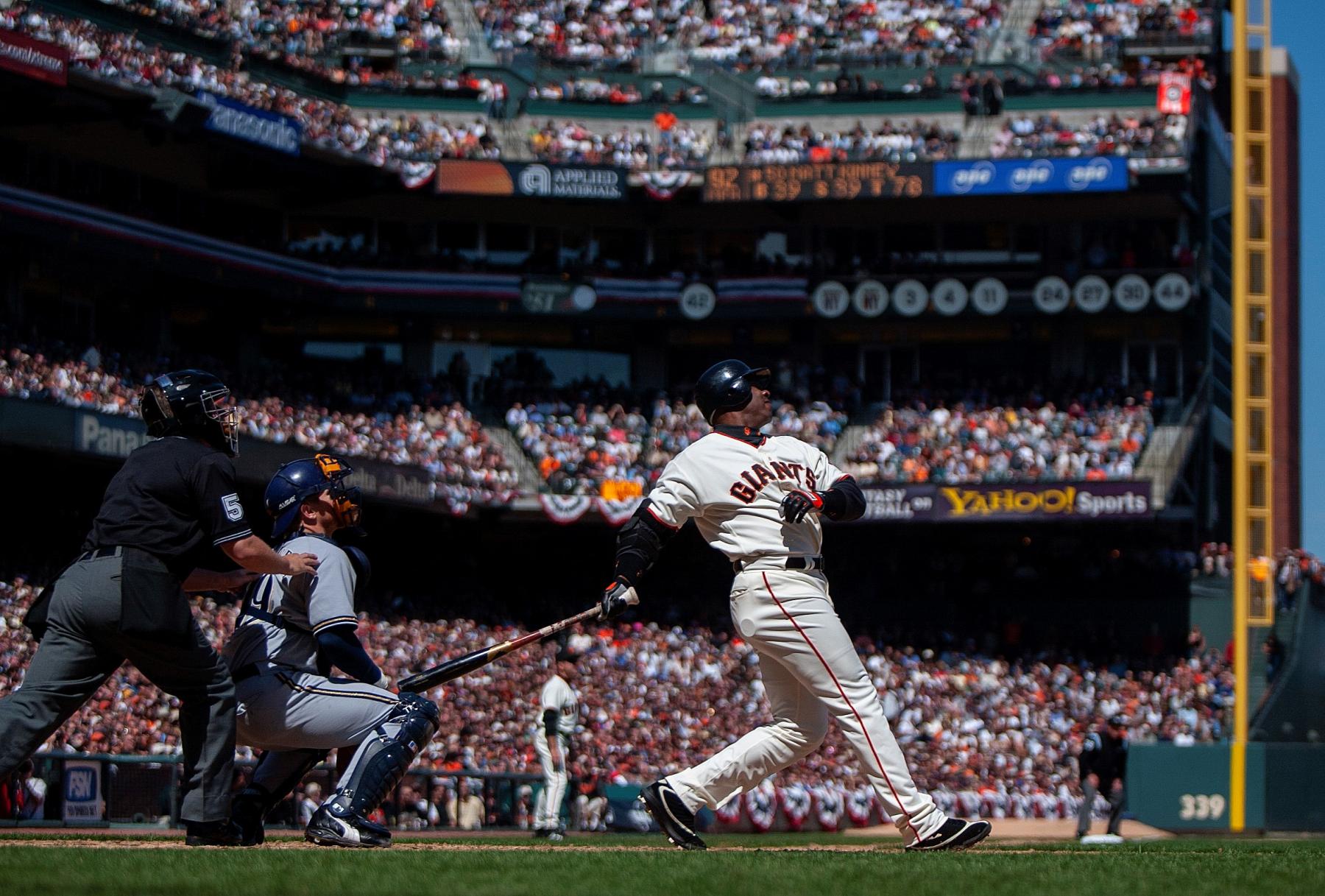

In 2004, when Bonds was on the cusp of tying Hall of Famer Willie Mays’ mark of 660 home runs, the Giants were playing at home in San Francisco at 1:20 p.m. Pacific time on a Monday. Sports Illustrated normally “closed” its magazine early in the day on Mondays, but for a chance to run an image of Bonds tying Mays, they told Mangin he had until 6 p.m. Eastern (3 p.m. Pacific) to send in a photo.

In Bonds’ third at-bat, at about 2:50 local time, he launched a three-run homer to right field off Milwaukee’s Matt Kinney. Mangin got a wide angle shot of it and a secondary photo of Mays presenting a “torch” to Bonds during a brief on-field presentation.

“Over Wi-Fi from my laptop, from the field, from San Francisco to New York, on deadline, with seconds to spare, it made it in 3.2 million magazines that week,” Mangin said.

Now the same images that used to appear so often in print, Mangin posts to his Instagram account in a matter of seconds. And he can shoot them with his iPhone. In fact, Mangin published “Instant Baseball,” a collection of pictures from the 2012 MLB season shot exclusively with his iPhone.

It’s Mangin’s unique way of proving that it’s not the equipment that defines the image, it’s the person who takes it. Though it’s also a pretty good indicator of: a) how far camera capabilities have come on cellular phones; and b) what’s possible through social media.

It seems the speed of the game — and the speed of the tools to both document and consume it — are only getting faster. And organizations like the new Professional Baseball Photographers’ Association are helping photogs navigate the new landscape.

“The digital aspect made shooting baseball so much more entertaining and engaging, caffeinated, high speed,” Compton said. “Back in the day, you might shoot the whole game and go in and process your film, but you’re sitting there play after play, falling asleep. You know how baseball is kind of a slow game and then all hell breaks loose. Three things happen at the same time…

“In the age of digital, between every inning I’m pulling the card out of my camera, running over to my laptop in the photo well. I’m copying the images, putting a caption on and I’m sending a couple of photos back between every inning. I’m keeping a flow going the whole game. I send 30 to 50 photos from a baseball game. You’re constantly in high-speed mode. It keeps you wide awake the whole game. When you get home at night, you can’t go to sleep. You’re just wired.”

Carroll Rogers Walton covered the Braves for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and is currently a freelance writer living in Charlotte.