- Home

- Our Stories

- Play It Again: The Two All-Star Game Era

Play It Again: The Two All-Star Game Era

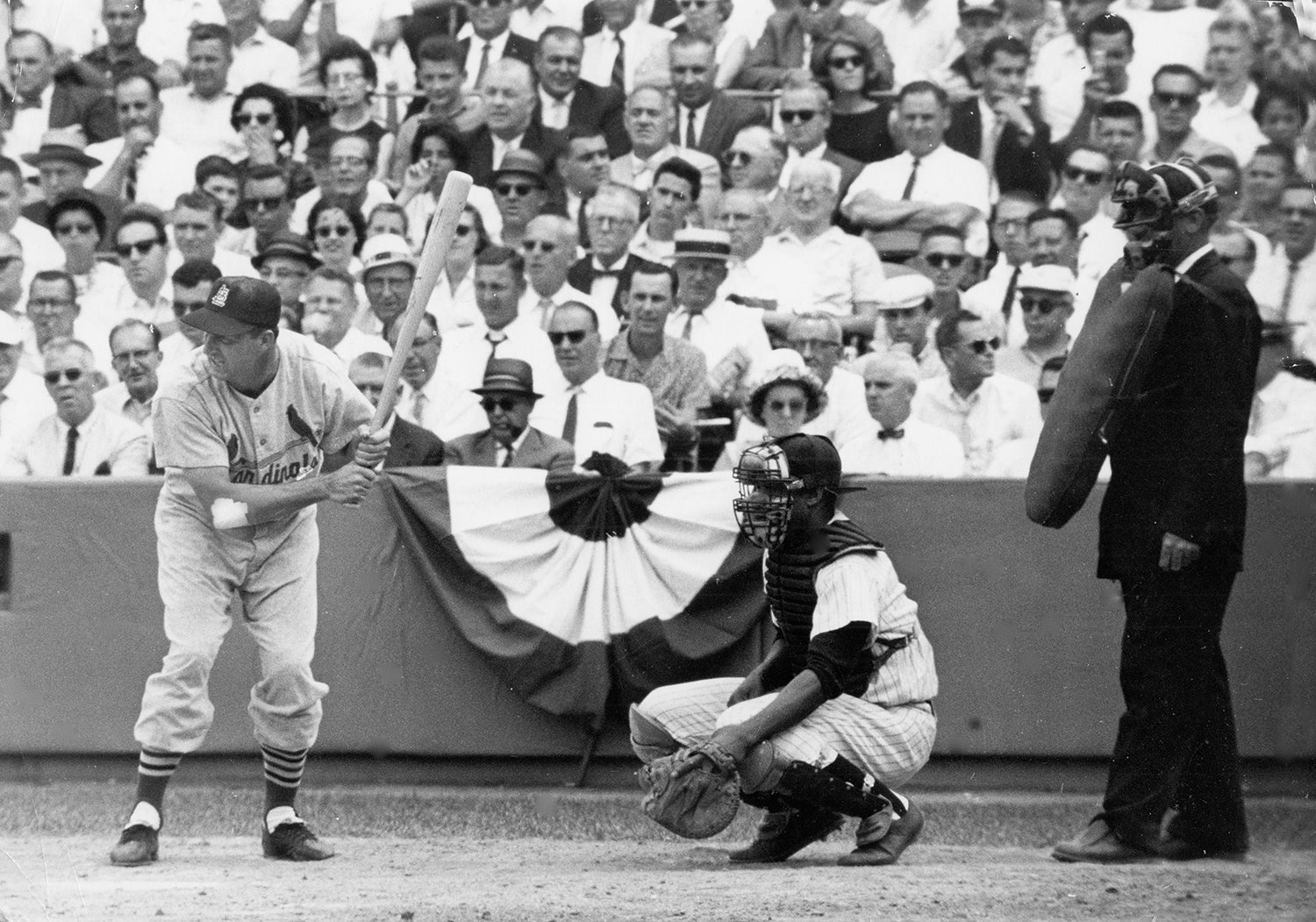

On a brutally hot midsummer afternoon in 1959, more than 55,000 fans filed into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum to watch the 27th Major League Baseball All-Star Game, a 5-3 American League victory.

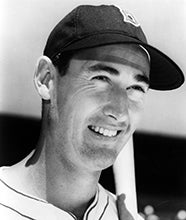

Angelenos, who had no big league club to cheer until the Dodgers moved west the year before, must have been over the moon watching Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Stan Musial and Ernie Banks dressed in their teams’ uniforms, playing in the grandest exhibition that American sports offered — even if hometown hero Don Drysdale of the Dodgers surrendered three runs and took the loss.

That Aug. 3 All-Star Game would have been otherwise unremarkable except for one thing: It was the second in four weeks. The first, largely featuring the same rosters, was played on July 7 at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, a 5-4 NL triumph.

Nineteen fifty-nine introduced a unique footnote to the history of the Midsummer Classic. In that season and the three that followed, the American and National Leagues played two All-Star Games.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Money was behind the second All-Star Game, although the motivation was altruistic. The players, led by Phillies pitcher and future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, devised the plan to raise more money for their pension fund, which was created in 1947 and distributed only a modest payment to retirees.

The dual All-Star Games were controversial from the get-go. Some hailed a set-up that brought stars from both leagues into more cities each summer at a time when interleague baseball did not exist, aside from the World Series, and few games were televised. On the other hand, more than a few critics in the press – who were not well-versed on the paucity of pension dollars available to players – decried the second All-Star Game as a “greedy grab” that would dilute what had become an extremely popular annual tradition.

Even some players who stood to benefit with larger pensions were skeptical.

“It’s the phoniest front baseball has put up in 20 years,” Chicago White Sox pitcher Early Wynn, a future Hall of Famer, was quoted as saying in contemporary newspaper reports. “They’ll get a pot full of money out of it this year, but wait until the novelty wears off. The game’s value is in its uniqueness. Two games a year will cheapen it in the long run.”

By 1962, players, owners and the press came to the same conclusion.

“The public at large is finding a second all-star attraction something of an anticlimax,” New York Times columnist John Drebinger wrote, “like playing a second World Series in Brazil.”

Baseball returned to a single All-Star Game in 1963 after team owners, tiring of the logistical issues that plagued the dual games and impacted pennant races, and finding it more difficult to shoehorn two All-Star Games into the 162-game schedule, agreed to funnel 95 percent of All-Star gate and broadcast revenues from a single game to the pension fund.

The eight games played between 1959 and 1962 produced five victories for the National League, two for the American League and the first All-Star Game tie when rain truncated the second 1961 game at Fenway Park.

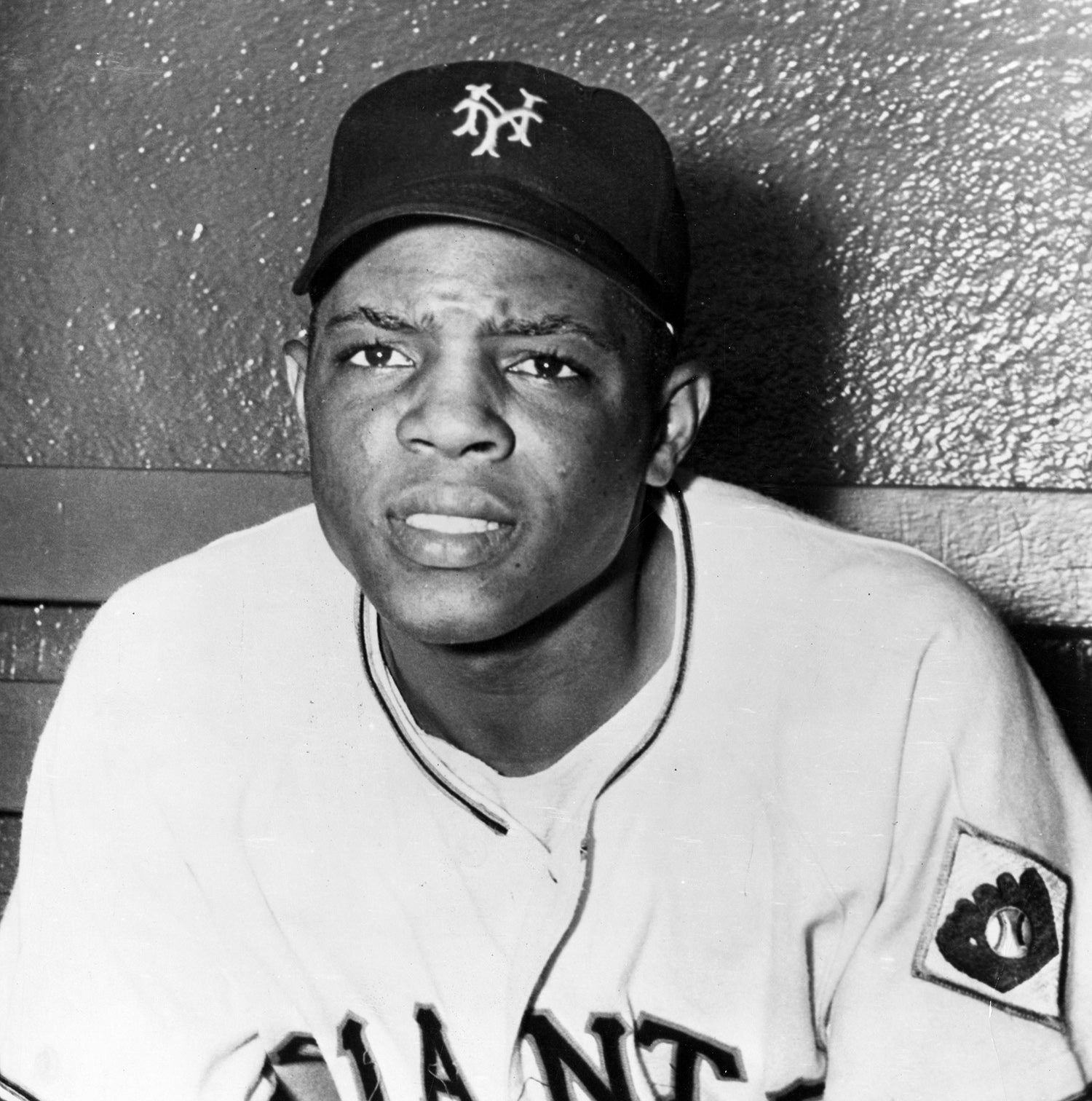

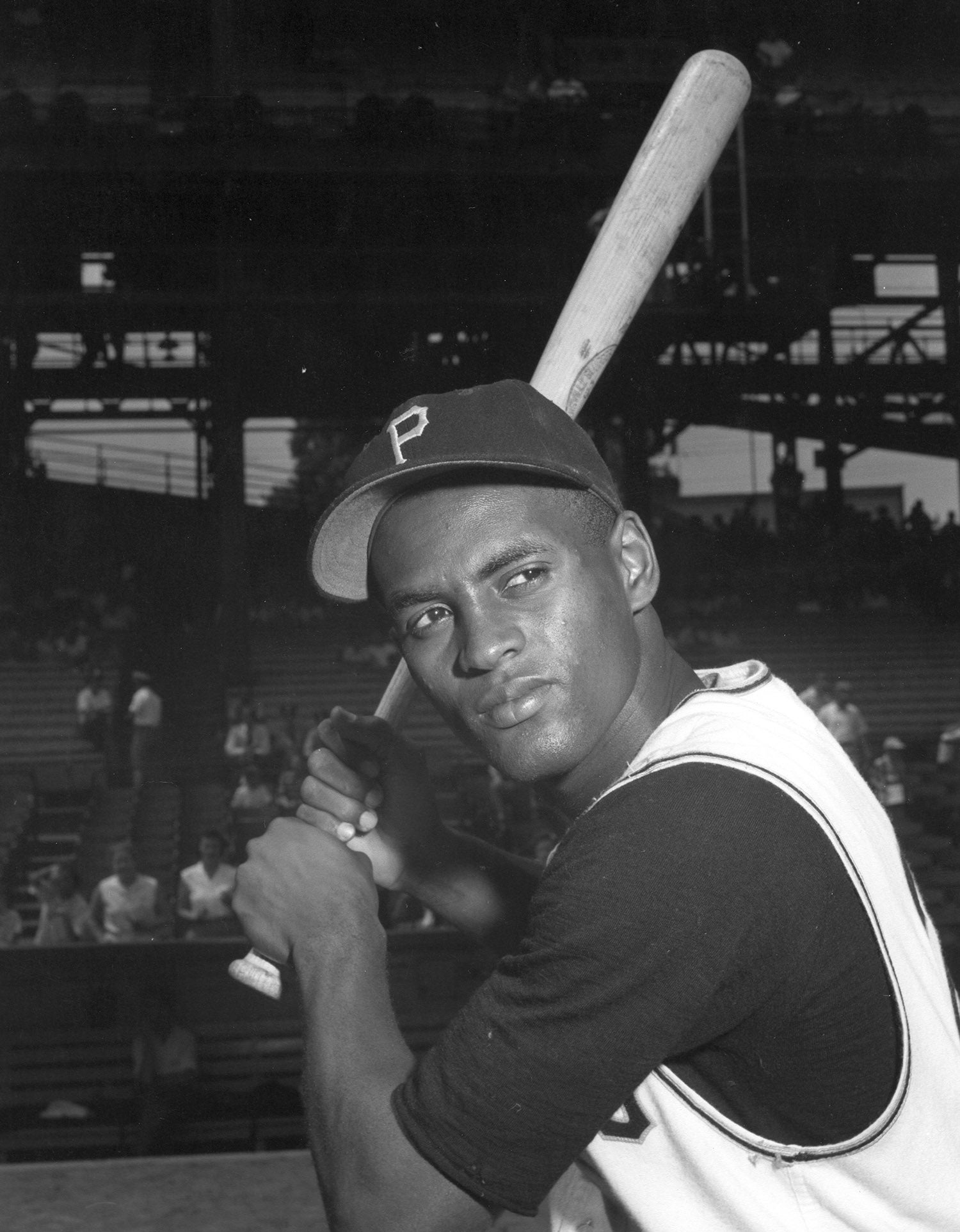

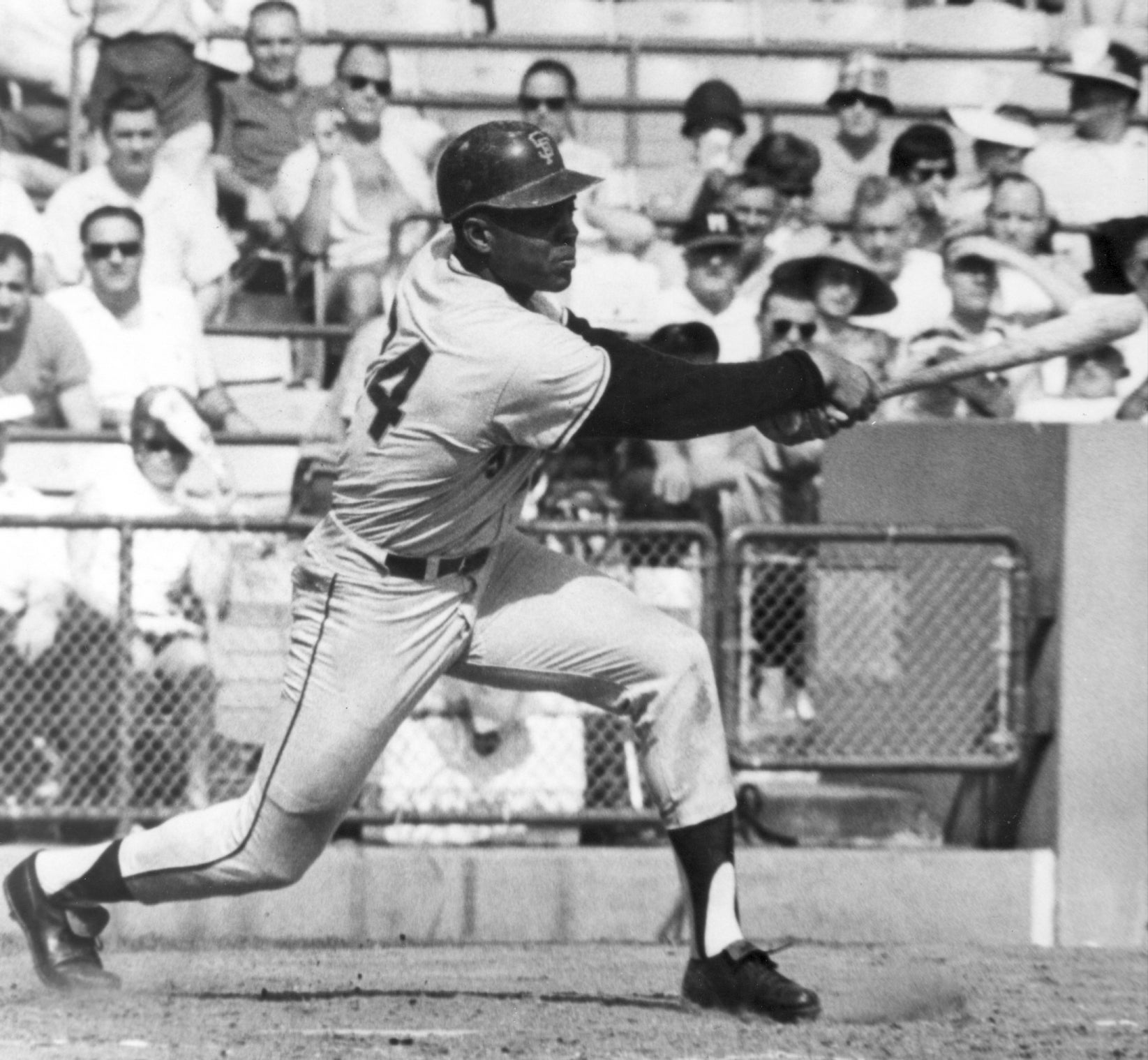

And while they did not produce any legendary moments, there were standout performances. Willie Mays, who hit a robust .414 during the eight All-Star Games between 1959-62, thrilled his home fans at Candlestick Park in the first 1961 All-Star Game when he hit a game-tying double in the 10th inning and then scored the winning run on a Roberto Clemente single.

Yes, the Say Hey Kid really was still around in the 10th inning. The biggest stars in those days did not come out of All-Star Games because wins and losses meant much more at a time when the leagues were separate entities.

In fact, it was eye-popping to see Mays replaced by the Reds’ Vada Pinson in the sixth inning of the first 1960 game, at Kansas City. Mays loved Pinson, who otherwise might not have seen action, and asked NL manager Walter Alston to make the move.

“Vada didn’t even have his glove,” Mays recalled in a recent interview with his biographer, John Shea. “When I went over there and told him, ‘Hey, man, you’re going to replace me,’ he said, ‘Get out of here. I know you’re not coming out.’”

When Mays told Pinson to find his glove, Pinson said, “Thank you,” and ran onto the field.

Mays knew he could be munificent with his innings since he would get another All-Star start two days later at Yankee Stadium. As for playing two All-Star Games in three days, Mays said, “It wasn’t that big a deal to me. I liked to play. I remember the same guys played both games. I enjoyed the All-Star Games myself.”

The most memorable “occurrence” in the dual All-Star years actually did not happen. Legend says Giants reliever Stu Miller was “blown off the mound” by a wind gust at Candlestick Park. Indeed, the wind was strong enough to cause Miller to sway, leading to a balk. However, as Miller said years later, “The next day in the paper the banner headline was, ‘Miller blown off mound.’ You’d think I was pinned against the center field fence.”

There was evidence that having two All-Star games diluted the product. The 1960 game at Yankee Stadium drew only 38,362 fans.

Logistics were an issue as well. MLB had to eliminate some off days to fit two All-Star Games into the championship schedule, especially in 1959, the first year of the experiment, when owners were eager to plant a second game in Los Angeles after the season schedule had been finalized.

Part of the deal with players gave owners 40 percent of the gate, and the teams foresaw a big payout at a park where, a year earlier, 93,103 attended an exhibition to honor former Dodger Roy Campanella, who was paralyzed in a car accident before the team moved west.

They held the game on a Monday, a day after every team played a regular game or even a doubleheader. Players reported being exhausted when they arrived after cross-country flights and even more so when they returned to their teams. Attendance was 55,105.

Over the next three years, owners wavered between playing the two All-Star Games in one mid-season break or spacing them several weeks apart. Teams bickered when All-Star managers wore out star pitchers who then had to rest when the season resumed. There were headaches, sure, but for a good cause.

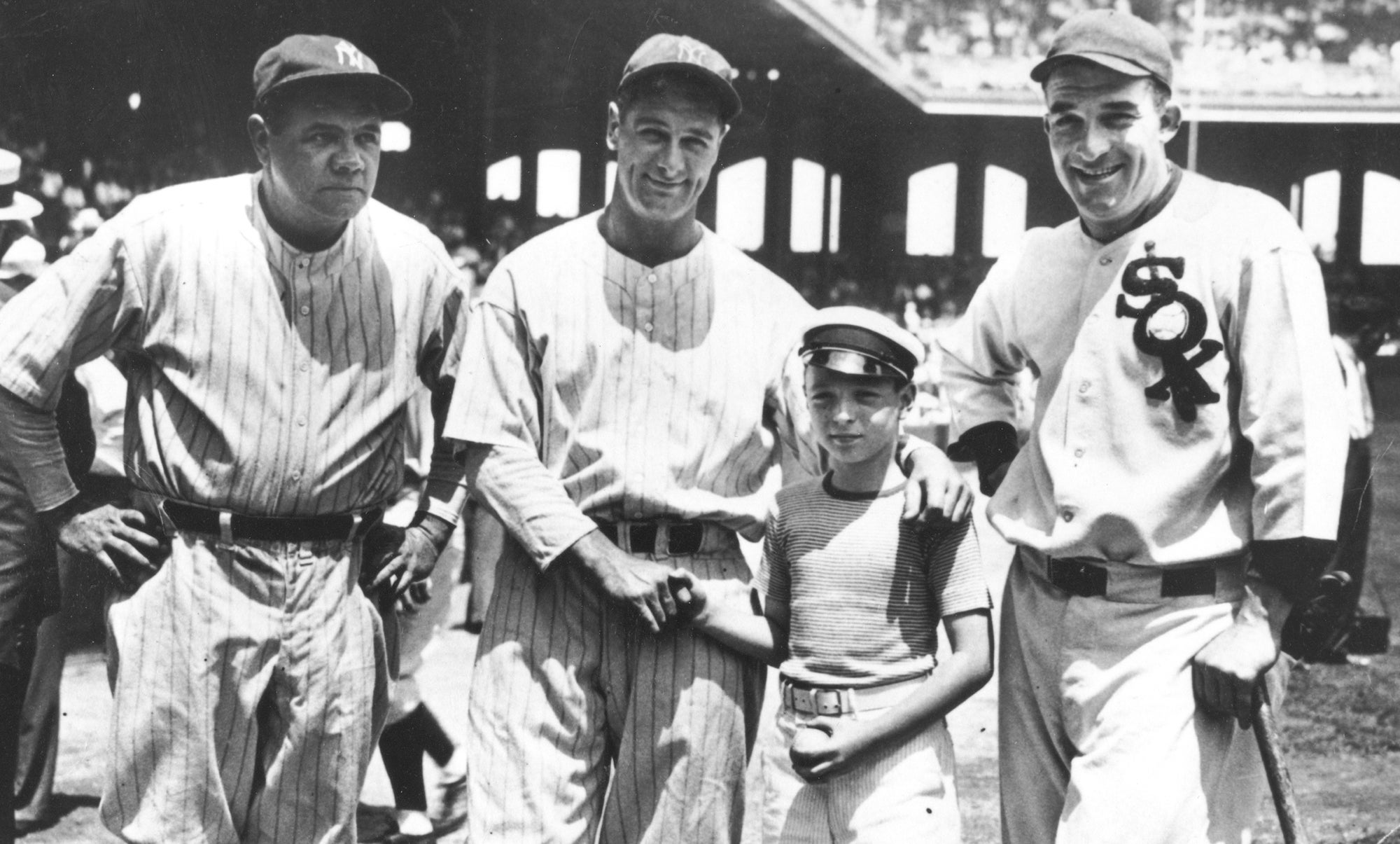

For most of the first half of the 20th century, there was no big league pension. A fund existed for retirees down on their luck and widows of players who died young, partly funded by their cut of All-Star Game revenues, but there was no formal mechanism to support players once they hung up their cleats.

Andrew Harner, a baseball historian who wrote an exhaustive article on the four years of the dual All-Star Games for the website www.howtheyplay.com (the source for many of the historical quotes in this story), said even big stars whose salaries were held down by the reserve clause were not set for life after they retired.

“And what about the guy who played five, seven, eight years as the third starter in a rotation making $10,000 to $15,000 a year?” Harner asked.

The tide changed in 1946 when players gained rare leverage. A new Mexican League had formed and was courting them to leave the American and National Leagues for bigger money, just as the nascent Federal League had done three decades earlier.

In a bid to keep players from defecting, owners made several concessions, including minimum salaries and establishment of a pension fund to which owners and players would contribute.

Even then, the money was not spectacular.

Harner said a player with five years tenure received $50 a month upon retirement, plus $10 a month for each additional year of service until he was fully vested at 10 years and received $100 a month, about $1,300 in today’s dollars. Nowadays, a fully vested major leaguer gets roughly $16,000 a month.

With the first big national TV contracts, pensions grew in the 1950s, which indirectly led to the dual All-Star Games because the players earned a cut of those revenues. The monthly payout increased for both current players and those in the league before the television money rolled in.

That generosity, however, created a $12 million pension-fund deficit that needed to be repaid over a number of years.

That’s where Robin Roberts came in. He proposed the second All-Star Game in 1959 to raise more money that could help chip away at the deficit more quickly.

“Robin Roberts was looking out for the older players,” said David W. Smith, co-author of “The Midsummer Classic,” a 2001 encyclopedic history of the All-Star Game. “He was definitely union-active and very concerned about the guys who were already retired.”

Said Harner: “I think he was just well-versed and an intelligent guy who saw a need for this and put a proposal together. He seemed like a sharp individual who saw what needed to be done, and he’d be the one to do something about it.”

In 1959, after discussions with player representatives from other teams, Roberts pitched the idea to Commissioner Ford Frick, who got the owners on board.

The extra games served their purpose. In 1959 alone, the pension fund grew by $750,000 from playing two games, but after four years, all sides said “enough,” and the short-lived age of dual All-Star Games became another bygone quirk of baseball lore.

Henry Schulman is a San Francisco-based freelance writer. He covered the Giants from 1988-2020 for the Oakland Tribune, San Francisco Examiner and San Francisco Chronicle.

Related Stories

MLB All-Star Game created a blueprint for other leagues to follow

MLB broke new ground with 1963 Hispanic All-Star Game

Mays’ pinch-hit homer leads National League to victory in 1956 All-Star Game

Musial hits 12th-inning home run to propel NL to win in 1955 All-Star Game

Fans fill Coliseum for Campanella tribute

Related Stories

Recalling Roberto

'Fastball' Headlines Tenth Annual Baseball Film Festival

Musial passes Speaker on all-time hits list

#Shortstops: Art Pennington: An Equal among Greats

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

Writers Elect Four to the Hall for the First Time in 60 Years

01.01.2023