- Home

- Our Stories

- MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

At first glance, it might seem that baseball and Martin Luther King Jr. had only a tangential relationship. King was a fan of the game but never played it professionally, never worked formally with organized baseball and rarely spoke publicly about baseball’s own struggle with civil rights.

Yet, there is far more to the story than that. Over the course of his short life, King developed strong relationships with several prominent major league players. And in the case of at least one of those players, King came to rely on him for counsel and advice throughout the 1960s, coinciding with some of the most tumultuous years of the Civil Rights Movement.

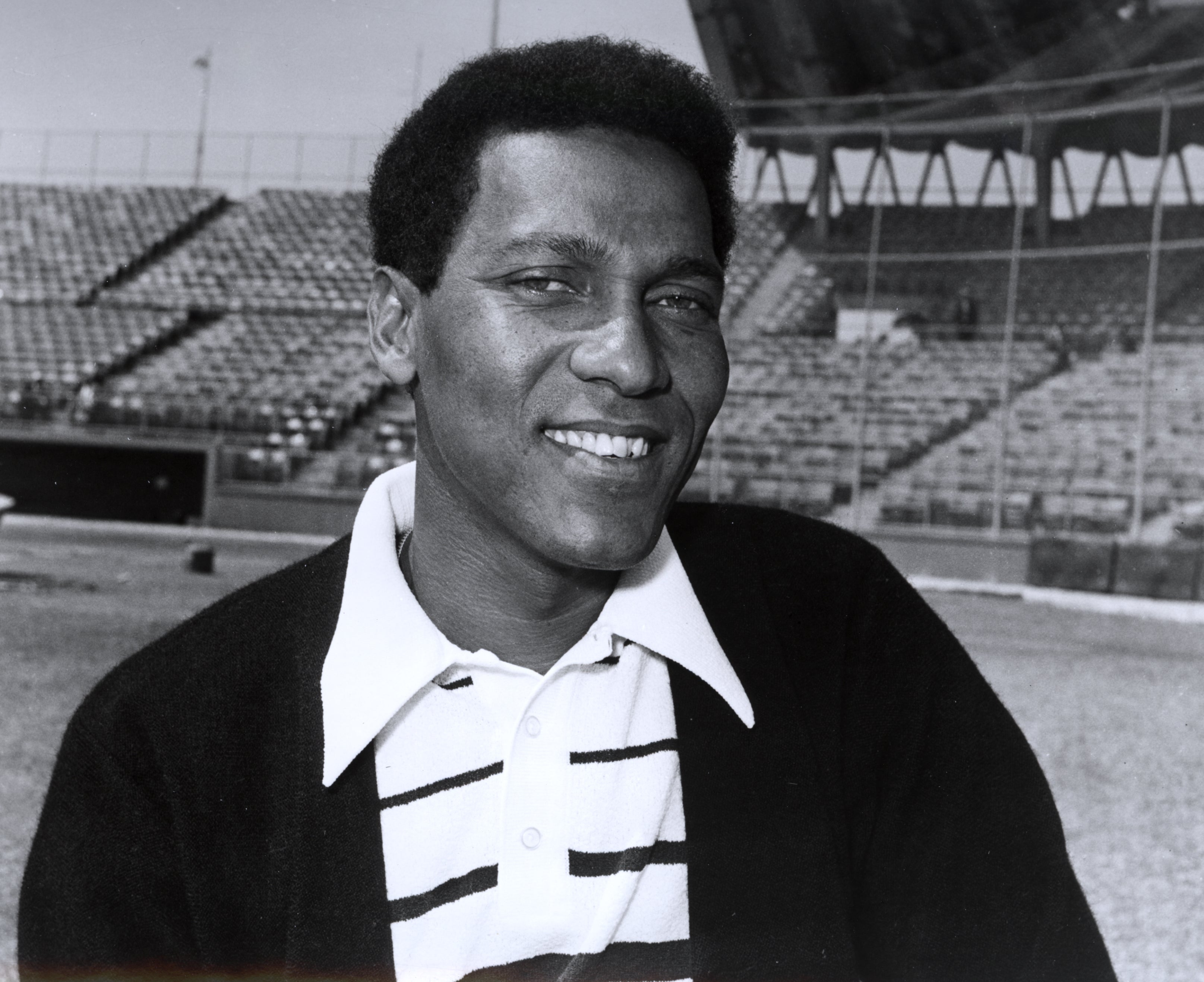

One of King’s most direct baseball connection dates back to the 1950s, when he became a close friend and trusted advisor to future major league standout Donn Clendenon. In the late 1950s, Clendenon attended Morehouse College, a prestigious all-Black school located within the city of Atlanta. Clendenon would star in three sports at Morehouse: Football, basketball, and baseball.

As part of Morehouse tradition, the college assigned incoming freshmen a mentor to provide advice and counsel. Typically, the mentors were drawn from the junior and senior classes and were assigned to work one-on-one with one of the freshmen. In Clendenon’s case, he already happened to know an alumnus of Morehouse: Martin Luther King Jr. himself. The Clendenon and King families both lived in Atlanta and were already friendly with each other, so a special arrangement was made to have King serve as Clendenon’s mentor. King, who often invited Clendenon to his house for dinner, helped the talented student-athlete adjust to life at Morehouse, while offering advice on the young man’s studies and future plans.

After graduating from Morehouse in 1956, Clendenon signed his first professional contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates, for whom he would debut in 1961. And as circumstances developed, King would come to know another prominent member of the Pirates and a longtime teammate of Clendenon.

The friendship that developed between Roberto Clemente and King has received little attention over the years. “Something interesting happened that not too many in the states know,” said Luis Mayoral, a longtime personal friend of Clemente. “Roberto told me that he had gotten together with Martin Luther King, in 1964 or ’65…They met in Puerto Rico, when Martin Luther King went down there to a little farm that Roberto had in the outskirts of Carolina (Puerto Rico). In that little farm, Roberto would build a restaurant and recreational area for families, called ‘El Carretero,’ which means ‘Man of the Road.’ In that little farm, that’s where they had that meeting.”

That meeting gave Clemente insight into King’s mission. “I think that was also a key relationship,” said Mayoral, “in relation to the development of Roberto Clemente, the fighter for social equality.” It also motivated Clemente to become one of the most outspoken players on the Pirates in demanding the team not be forced to play on Opening Day after Dr. King’s death in the spring of 1968.

Donn Clendenon played in more than 1,300 National League games across 12 years, hitting .274 with 159 home runs and, in 1962, earning a second-place finish in NL Rookie of the Year voting. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Although one was a Black American and the other Latino, King and Clemente found common interest in the Civil Rights Movement. For years, Clemente had referred to himself as a double minority – both Latino and Black. He had faced racism on two fronts, one due to the color of his skin and the other because of his Spanish accent.

Clemente’s fondness for King remained with him the rest of his life. In March of 1970, a special all-star game – the East-West Major League Baseball Classic – was played at Dodger Stadium. The game featured legendary stars from both leagues, including Clemente, Hank Aaron, Johnny Bench, Willie Mays, Frank Robinson and Tom Seaver, with proceeds given to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights organization founded by King. For participating in the game, Clemente received a special King medallion. According to Mayoral, it became one of Clemente’s most prized possessions. Many years later, Clemente’s widow, Vera, gave the King medallion to Mayoral, who in turn donated it to the Texas Rangers’ museum.

King also developed a friendship with another prominent player, whom he would come to trust for his wisdom and experience: Jackie Robinson. The two men first met during the spring of 1949. As Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers made their way north from Spring Training in Florida, they were scheduled to play an exhibition game in Atlanta. Prior to the game, the Dodgers received a telegram from the leader of the Atlanta Ku Klux Klan, who threatened to kill both Robinson and Roy Campanella, the standout Black catcher who had starred in the Negro Leagues, if they played in the game. Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey was so concerned by the death threat that he contacted King, who advised him to bring both players to Atlanta. A frequent recipient of death threats himself, King invited Robinson and Campanella to his home for dinner. According to the book, Bums, An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers, King offered them encouragement, telling the players: “Don’t worry about these threats. You carry on just as you’ve been doing.”

King and Robinson would speak again in the mid-1950s. After Robinson was traded from the Dodgers to the New York Giants in December of 1956, he decided not to report to his new team, instead opting for retirement. As much as Robinson had done for the civil rights movement as a player, he wanted to become even more involved in civil rights activities in the next stage of his life. At some point in 1957, King contacted Robinson, encouraging him to take a more active role in civil rights affairs. In June of that year, the two men were invited to attend commencement activities at Howard University, where they both received honorary doctorates. King and Robinson stood next to each other during the ceremony, each wearing graduate caps and gowns.

Knowing of Robinson’s experiences in fighting racism during his baseball career, King came to rely on the retired Dodgers’ star for his counsel on various matters related to his civil rights plan. They often appeared together at protests and demonstrations. During one public appearance in 1962, King praised Robinson directly: “You have made every Negro in America proud through your baseball prowess and your inflexible demand for equal opportunity for all.”

Not surprisingly, King and Robinson became friends, developing a strong loyalty toward one another. On several occasions, King was arrested for his involvement in public protests. After one such incident, Robinson arranged for a benefit jazz concert to take place at his home in Stamford, Conn. All of the funds went toward King’s bail, helping him to gain his release from jail.

As well as King and Robinson worked together, they did not always agree on political issues. For example, King was vehemently opposed to America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. In contrast, Robinson believed that the U.S. needed to make a full-out effort to win the war in Asia. Robinson so staunchly believed in that position that in 1967 he publicly criticized King for his pacifist position. In an open letter published by the Chicago Defender, Robinson wrote: “I am confused, Martin, because I respect you deeply. But I also love this imperfect country.”

For two lesser men, such public disapproval might have caused a permanent rift, but King accepted the criticism and took the philosophical approach that it was not necessary for them to agree on every topic. They remained close friends until King’s death in 1968. As King once said of Robinson’s impact on his own life: “Jackie Robinson made my success possible. Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did.”

In addition to Robinson, King also came to know one of his Dodgers teammates, pitching ace Don Newcombe. According to Newcombe, King visited his house shortly before his death. During a dinner with Newcombe and his family, King made a point of thanking him for the part that he had played in integrating the Dodgers.

Roughly one month later, King traveled to Memphis, Tenn., where he wanted to show his support for sanitation workers who had gone out on strike. As he stood on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel, he was struck in the face by a single bullet. King was immediately taken to a local hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

The assassination of King occurred on April 4, 1968, just four days prior to Opening Day of the major league season. No team was more affected by the tragedy than the Pirates, whose roster featured 11 Black players, including Clendenon and Clemente. Facing pressure from team management and Major League Baseball to play their Opening Day games as scheduled, the Pirates resisted. Clendenon and several other Pirates led an effort to postpone the opener in Houston. Maury Wills, the Pirates’ player representative, said that out of respect for King the team did not want to play that scheduled opener, set for Monday, April 8. When the players learned that King would be buried on Tuesday, and not Monday as originally scheduled, they asked Pirates management to postpone the season’s second game as well.

“We feel we cannot play these games out of respect to Dr. King,” Clendenon said in an interview with the Sporting News, “since we have the largest representation of Negroes in baseball on the Pirates.”

Ultimately, the efforts of the Pirates’ players forced baseball’s hand. In response, Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown offered a solution: The team would not play on either Monday or Tuesday, but would play on Wednesday, April 10, which had originally been scheduled as a travel date. At a clubhouse meeting, the Pirates players voted unanimously to accept Brown’s plan.

As it turned out, in a full-fledged tribute to King, none of the 20 major league teams played on either Monday or Tuesday. All teams opened their seasons on Wednesday.

While it rankled many of the players that baseball took several days to respect their wishes, the decision to postpone Opening Day reflected the impact of King on a game that had become so heavily integrated during the 1960s. Only 22 years earlier, no Black players had played in either the American or National leagues. But by 1968, Black Americans comprised roughly 15 percent of major league players. For teams like the Pirates, Braves, Dodgers, Cardinals and Giants, it had become commonplace for three, four, or five Black players to take the field at the same time.

It's difficult to quantify how much of an impact King himself had on baseball’s continuing integration in the 1960s. Yet, there is little doubt that the civil rights leader cared about the game and respected the thoughts of its players. To King, they were not merely ballplayers; they were his constituents, an important part of an American culture that he hoped to change.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

Related Stories

Leon Wagner fought battles on and off the field

They also played: Black women in baseball

Lucas broke barriers in Braves’ front office

O’Neil’s work as a scout opened doors for many players

Charlie Grant’s brush with the big leagues

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Pastime Presents: Museum’s 75th Anniversary Offers Fans Unique Gift Opportunities

Davey Johnson’s managerial skills lead him to Cooperstown’s doorstep

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jim Roland

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

The Negro National League is Founded

He Never Complained

Griffey Jr., Piazza elected to Hall of Fame

Frank Robinson made history in AL and NL

A’s shut down Big Red Machine in thrilling Game 7

01.01.2023