- Home

- Our Stories

- Charlie Grant’s brush with the big leagues

Charlie Grant’s brush with the big leagues

Most Americans know full well that Jackie Robinson broke the National League color barrier in 1947, reintegrating a game that had been divided by skin color since the 1880s. It is not as well known that the game almost saw the color barrier toppled nearly 50 years earlier, when a Hall of Fame manager tried to bring a Black player into the fold with a daring move of subterfuge and trickery.

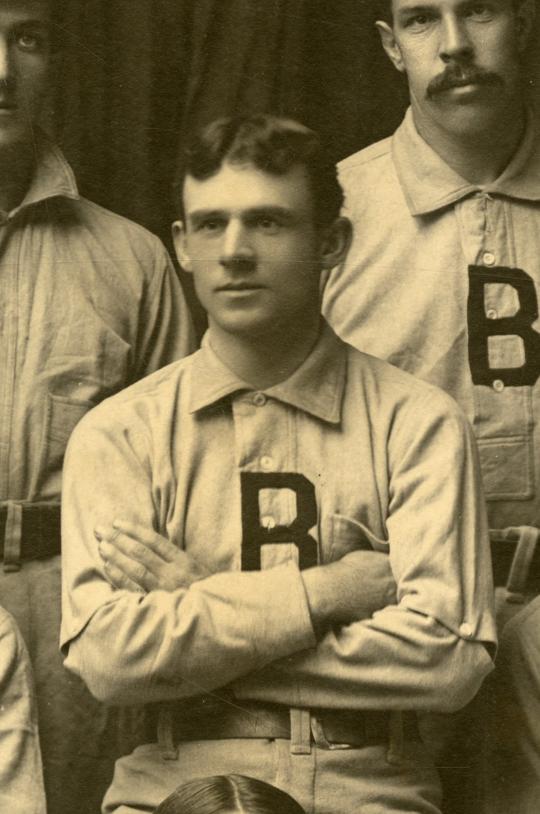

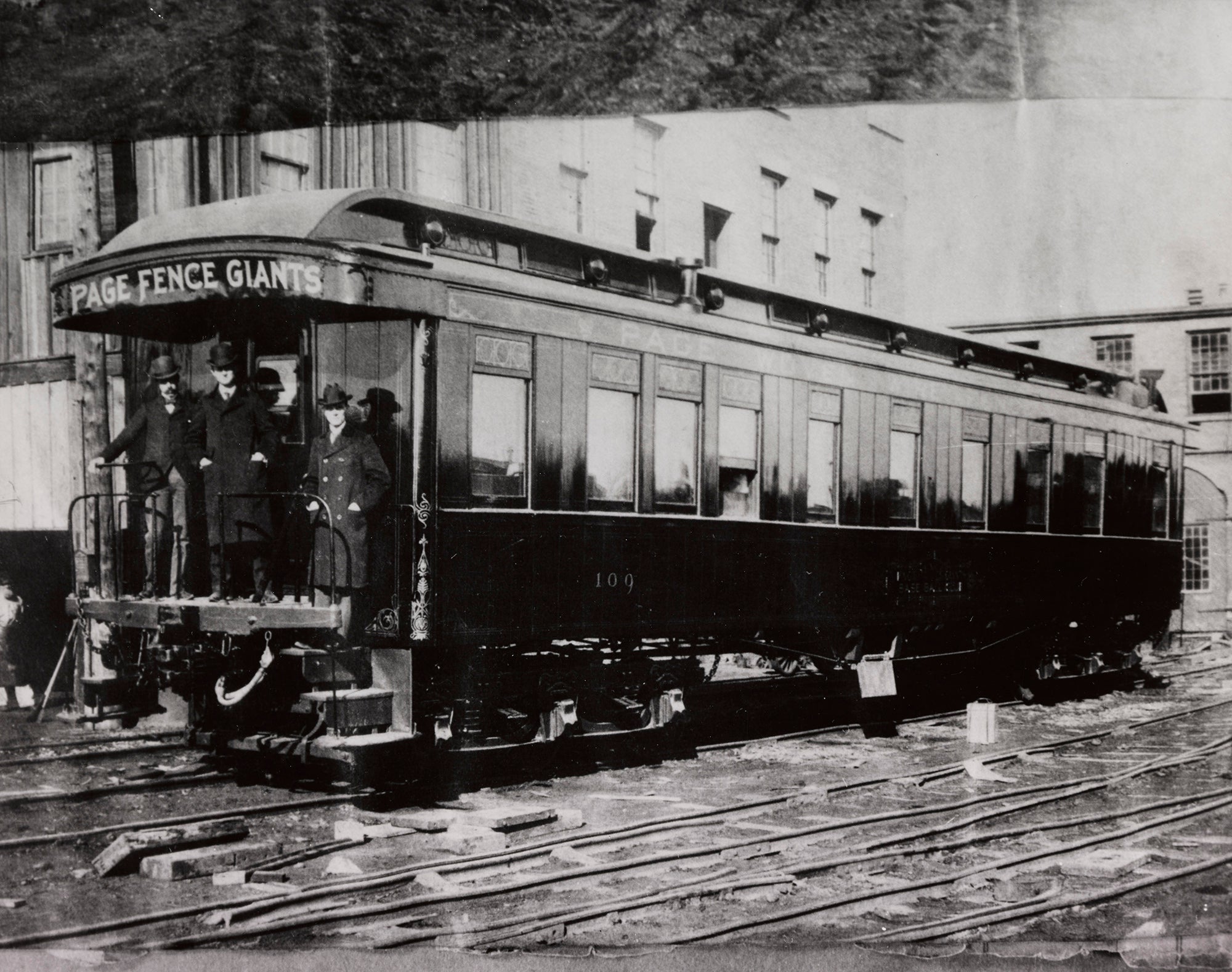

Charlie Grant, a solidly built second baseman with speed and range, first played the game professionally in the 1890s. In 1896, he joined the Page Fence Giants – the legendary barnstorming team that was profiled earlier in our Black Baseball Series. Grant emerged as the starting second baseman for the Giants, replacing Sol White at the position. Grant would remain with the Giants through their final season of 1899 before moving on with a number of his teammates to the Columbia Giants, a Black team in Chicago that became somewhat of an extension of the now defunct Page Fence team.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

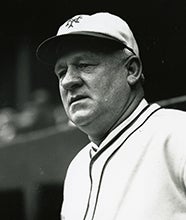

In 1901, Grant would experience a chance encounter with John “Muggsy” McGraw, the legendary manager of the Baltimore Orioles. In February of that year, the Orioles’ manager and part-owner visited Hot Springs, Ark., so that he could partake in a short vacation before the start of Spring Training.

As it turned out, Grant was working in Hot Springs, where he served as a bellhop at the sprawling resort, the Eastman Hotel. Like Grant, many other Black players found employment in Hot Springs during the winter months. They typically worked at hotels, bath houses and other local businesses in the months before the start of their own barnstorming seasons.

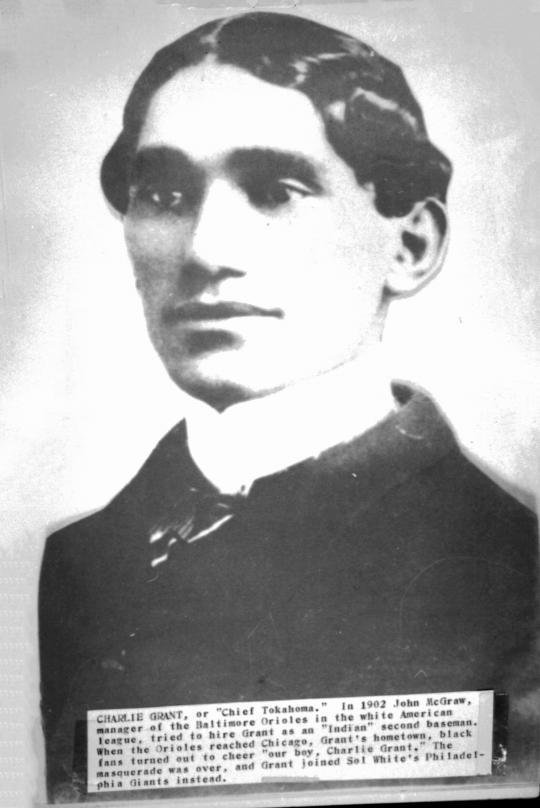

While working at the Eastman that February and early March, Grant encountered McGraw. It’s not certain if the two men knew each other from their previous baseball travels, or if they met for the first time in Hot Springs. According to a Black infielder named Dave Wyatt, he was the one who approached McGraw about the possibility of offering Grant a tryout. Knowing about the existence of the color barrier, Wyatt introduced Grant as a Native American. With his lighter skin and straight hair, Grant looked Native American to some observers, giving Wyatt the idea of pulling off the charade.

As part of the ruse, Wyatt manufactured a name for Grant, calling him Grant-a-Muscogee. Later on, Grant was given the name of “Tokohoma.” In later years, Wyatt would admit to knowing that McGraw was not fooled by any aspects of this cover story, but the manager was willing to go along with the concoction as a way of facilitating a tryout. McGraw would eventually endorse the Native American backstory, promoting him as being a full-fledged Native American, knowing that was the only way that he could pass as being sufficiently “white” for American League purposes.

On either March 8 or 9, a tryout was arranged on the lawn of the Eastman Hotel. Not only was McGraw in attendance, but so was Clark Griffith, the player-manager of the Chicago White Sox who also happened to be in Hot Springs. Griffith hit an array of ground balls in the direction of Grant, testing his fielding prowess to the fullest. As the Chicago Tribune described, “[Grant] was tried on all kinds of hard ones and the more McGraw saw him play the better he liked him. The Indian stopped everything that came his way, covering a large amount of ground, and handling himself like a natural-born ballplayer.”

McGraw came away so impressed with Grant’s fielding skills that he told several baseball writers that he planned to bring the second baseman to the Orioles’ Spring Training camp. The Orioles, who had a major need at the pivot position, had previously signed 34-year-old veteran Heinie Reitz, a player who had been out of the major leagues for more than a year and seemed like only a stopgap solution.

On March 11, McGraw announced that the Orioles had signed Grant, whom he identified as a “Charlie Tokohama” (a slight variation of the original Tokohoma and one that the media would often use). McGraw explained that Grant/Tokohama was a member of the Cherokee Tribe. According to newspaper reports, McGraw continued to work with Grant in Hot Springs, putting him through routine drills and giving him advice on fundamental play.

In an article that appeared in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Grant quickly attracted the attention of the baseball world. “Muggsy McGraw’s new discovery, an Indian ballplayer from the Indian Territory, has been the sole topic among baseball players here this week. The Indian is really a first-class, natural player. Handles himself exceedingly well on ground balls.” The article went on to perpetuate the myth surrounding Grant’s background. “His name is Tokohoma, and his parents are full-blood Cherokees. ‘Tokie,’ as he is called, weighs 170 pounds and is built on the lines of an athlete.”

The plan initiated by Dave Wyatt and put into effect by McGraw seemed to be working. Joining the Orioles for Spring Training, Grant worked out with the team in anticipation of being a part of the Opening Day roster. But then newspaper stories surfaced, contending that Grant was not a Native American, and was actually another Black player, a well-known second baseman named Frank Grant.

McGraw decided to play off the confusion of Charlie Grant with Frank Grant. As McGraw explained to one reporter, “He is a real Indian and not the Negro Grant as alleged.” Charlie Grant responded to the mix-up by doing an interview of his own, in which he contended that his mother was of Cherokee descent and living in Lawrence, Kan., while his father was white. McGraw continued to back up Grant’s claims, hoping that he could maintain the ruse and keep his talented second baseman on the roster for Opening Day.

Grant and McGraw did their best to keep the situation under control, but further problems arose when Grant and the Orioles traveled to Chicago, the city in which he had played for several years. A group of Grant’s Black friends staged a reunion, including a visible and publicized ceremony in which they honored the returning player. Charles Comiskey, the owner of the Chicago White Sox, became aware of the ceremony. It’s also possible that Comiskey had been informed of Grant’s true identity by White Sox manager Clark Griffith. Comiskey voiced his objection over Grant, contending that “Tokohama” was an alias and that he was not Native American, but Black.

McGraw soon realized that the fabricated back story was not holding up under scrutiny. Rather than admit that Grant was indeed Black, McGraw started to back off on the endorsement of his new second baseman, referring to him as “inexperienced,” particularly in terms of his defensive play. Shortly thereafter, McGraw revealed his Opening Day roster, which no longer included Grant. It’s not known if American League President Ban Johnson played a part in the decision, or if McGraw had made the choice to cut Grant on his own.

Whatever the decision-making process, Grant was left out in the cold and did not travel to Baltimore. He had no other choice but to return to Chicago and the Columbia Giants. His dream of playing in the major leagues, learning under the tutelage of McGraw, had come to an end. Despite later rumors of Grant being told to report to Baltimore, he never rejoined the Orioles and never received another tryout to play in the major leagues.

Grant remained with Columbia through the end of the 1901 season and then continued his long career with several other Black teams before retiring in 1916. In his post-playing days, he found work as a janitor, eventually working for a company called Thomas Harris and Sons.

On July 9, 1932, Grant was sitting in front of the Cincinnati apartment building where he worked, when a passing automobile experienced a blowout of its tire. The blowout caused the driver of the vehicle to lose control, veer off the street and jump the sidewalk, before crashing into Grant. The horrific accident killed Grant, who was just 57.

Grant’s death occurred under a veil of obscurity, much like the majority of his playing career. It might have turned out very differently if only John McGraw had succeeded in pulling off his great caper of racial identity and making Charlie Grant an iconic civil rights pioneer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Page Fence Giants succeeded on and off the field

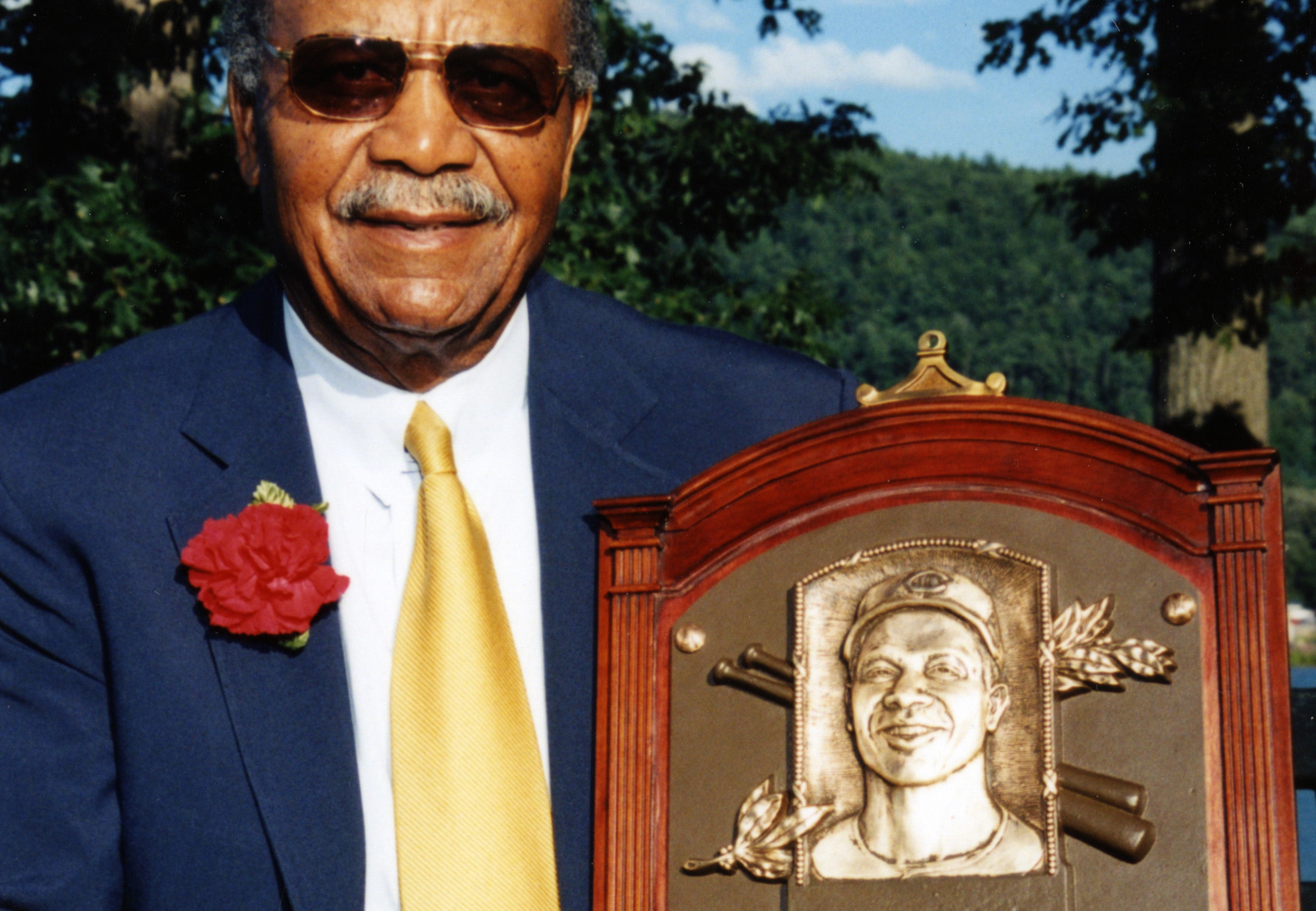

Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

Eddie Leonard’s Loving Cup for John McGraw

Banks transitioned seamlessly from Negro League to Cubs

Related Stories

Baseball and the Funny Papers

Exhibition complements exhibit as Hall celebrates Black baseball history

Negro Leagues History Digitized in Museum’s Latest Additions to PASTIME

The complete story of Jackie

Gary Herrmann - A King in Queen City

Hall to Honor Curt Flood’s Legacy, World War II Players during Awards Presentation at HOF Weekend