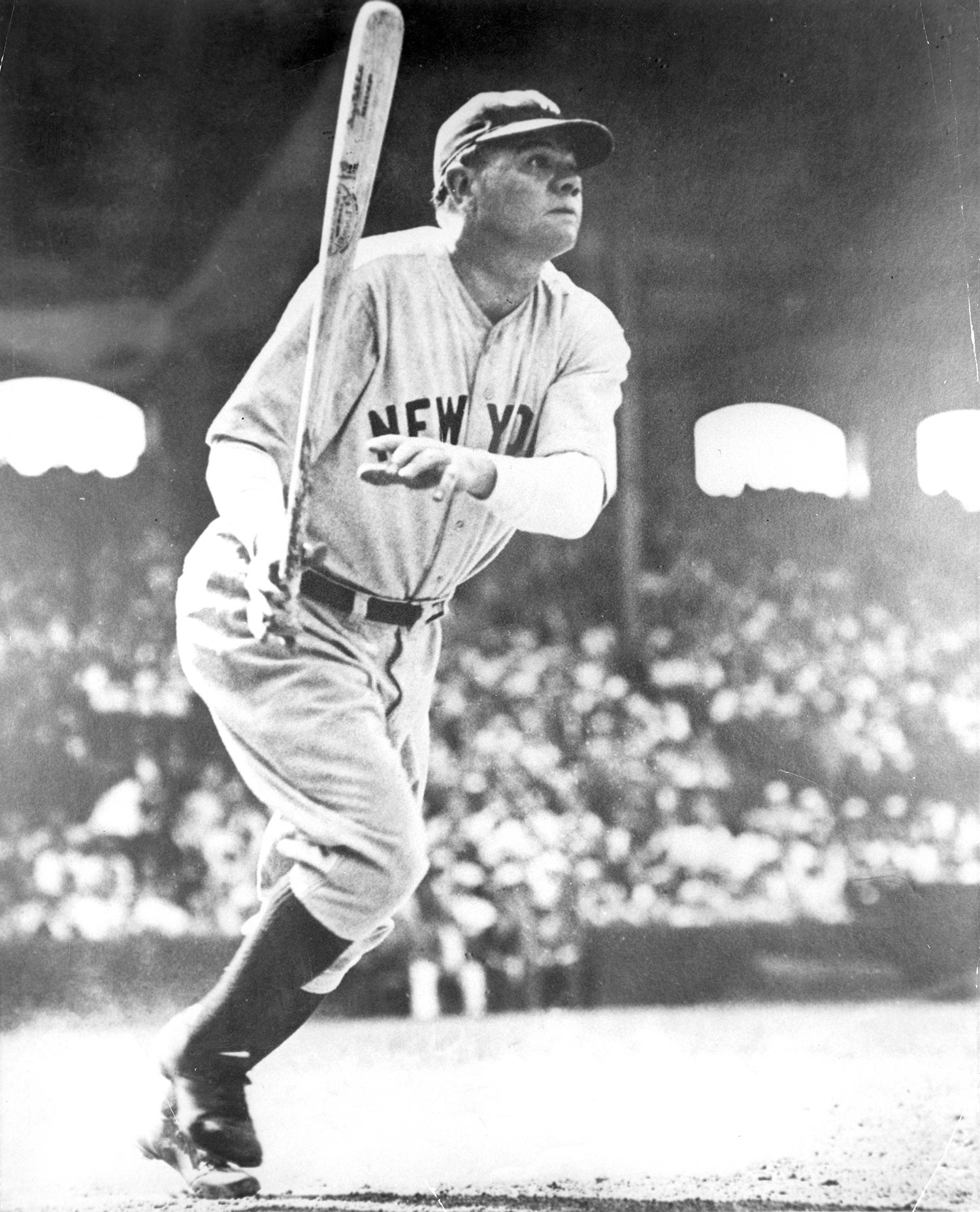

Back to Babe: The Nat Fein photo

Shortly after reporting to the Manhattan offices of the New York Herald Tribune on the morning of June 13, 1948, Nat Fein was told he would need to fill in for one of the sports photographers who had phoned in sick.

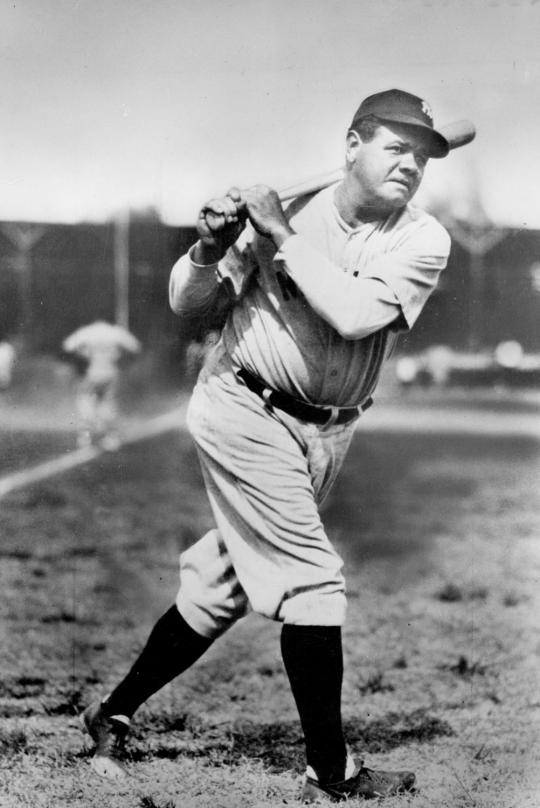

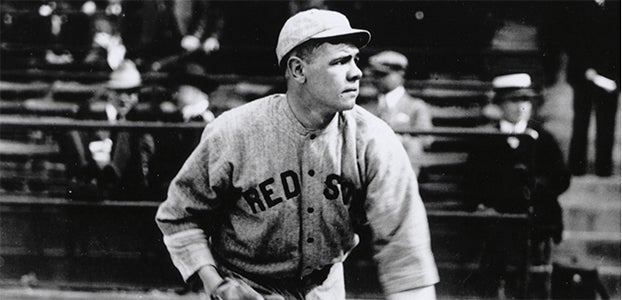

Though Fein’s specialty was human-interest photography, he occasionally shot sporting events for the famous newspaper known as the Trib, so he wasn’t going into the assignment blind. His eye for the evocative figured to come in handy this day because the Yankees were retiring Babe Ruth’s famous No. 3 jersey, and Fein’s editor wanted images that captured what was sure to be an emotional afternoon at Yankee Stadium. The Bambino was dying of throat cancer, so this was likely a requiem for the 53-year-old slugger; his last appearance wearing his famous pinstriped uniform in the quarter-century- old edifice that had become known as “The House That Ruth Built.”

Yankees Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“It’s interesting that a prop in arguably the most famous photograph in baseball history was a bat from a player who one day would join the Babe in Cooperstown, and a player known for using his arm rather than his bat,’’ said Michael Gibbons, the executive director emeritus of the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Museum in Baltimore. “Feller didn’t find out about his supporting role in that iconic photo until later because he was out in the bullpen, getting ready to pitch that day.”

Like his fellow photographers, Fein took numerous frontal shots of the Babe, including one of him doffing his cap to the adoring crowd of 49,641 fans after he had stepped onto the field to thunderous applause. Fein then joined his kneeling counterparts along the first base line where current and former Yankees were standing.

“By this point, Nat had everything he needed, but he had one shot left,’’ said filmmaker Frank LoBuono, who wrote and directed a still-to-be-aired documentary titled Nat Fein: A Talent for Living. “He said to himself, ‘I want to do something different. What can I do?’ And this is where Nat’s true genius comes into play.”

Fein decided to break away from the pack and violate the photojournalism commandment of never shooting a subject from behind. He scurried over to the third base side, peered into his view finder and framed the shot that accentuated the Babe’s No. 3, with the massive ballpark as the backdrop.

“The boss told me to go up to Yankee Stadium because that was the day Babe Ruth was retiring and this would be one of the last times to get a shot of the Babe’s No. 3,’’ the late Fein recalled in a 1986 interview with the White Plains (N.Y.) Journal News. “He drilled into me to get that No. 3, so that’s what I did. I took a lot of shots, but there was that one from the back with that No. 3 over those spindly legs.”

He also displayed his genius by violating another photographic tenet of the times by shooting the photo without flash “to give it added dimension.”

In those pre-digital camera days, a photographer didn’t really know what he/she had until they developed the film in the chemical tub of a dark room.

“He thought he might have something really different, something dramatic, but you never know until you see it come to life,’’ said David Nieves, a longtime friend of Fein’s who wrote a book about the stories behind the photographer’s most famous photos and is executor of his estate. “Now, everything with photography is instantaneous. Back then, you discovered what you had in that dark room. There was something magical about the process.”

In the hours, days and weeks that followed, Fein couldn’t help but reflect on his remarkable journey. An only child of Jewish immigrants, he grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the Great Depression. His father, Hyman Fein, worked as a touring singer with renowned composer Irving Berlin and wound up abandoning the family, leaving Nat’s mother, Frances, in the lurch. As a single mom, she did her best to make ends meet, working long hours as a seamstress in the garment district. A year after graduating from Brooklyn’s Erasmus Hall High School in 1933, Fein took a job as a copy boy in the Trib photo department for $10.86 a week.

The filing of photographs piqued his interest, and he asked his mother to help him buy a camera. She convinced three people to co-sign a loan so Fein could purchase his own Speed Graphic for $96 — a huge amount of money in those days. Before long, Fein was sneaking into the Trib’s dark room in the wee hours to practice developing his photographs.

A veteran photographer caught him in there late one night and complained to Crandell, who became so angry he almost fired Fein. But a few other photographers came to the copy boy’s defense, convincing Crandell that “the kid had a passion that should be nurtured, not punished.” The photo editor reluctantly agreed, and over time became one of the most influential people in Fein’s illustrious career.

Around 1936, he was hired as a full-time photographer — Fein called it the happiest day of his life — and from that point until the paper folded 30 years later, he established himself as one of the most celebrated photojournalists of the 20th century. He chronicled the well-known (Albert Einstein, John F. Kennedy and Queen Elizabeth were among his subjects) and the unknown, as well as animals, great and small. And he would capture the history and the feel of New York City like few others.

By the time of his death at age 86 in 2000, Fein had taken more than 50,000 photographs and had won more awards than virtually all his contemporaries. But the one shot that continues to stand out is that one of the Babe. Part of its enduring appeal has to do with Ruth, who remains a well-known public figure 75 years after his death. Part of it has to do with the poignant circumstances surrounding the photo. But, as Baseball Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber points out, the most important factor in the lasting nature of the image is the “absolute mastery” of Nat Fein.

“Like other photographers that same day, Fein captured images of Ruth facing the camera, his countenance instantly recognizable,’’ said Shieber, who used Fein’s photo and the uniform the Bambino wore that day as the focal point of the Hall’s immensely popular exhibit Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend. “But in ‘The Babe Bows Out,’ Fein embraces Ruth as a solitary figure, standing alone literally and figuratively. Also, quite literally, Ruth is the focus of the image — everything surrounding him recognizable and yet out of focus.”

Shieber notes that by photographing Ruth from this vantage point, Fein included so much of the Babe’s story: The slugger’s iconic No. 3; the packed stands and distinctive façade of the ballpark where Ruth had made his legend; various pennants from many of his championship teams; and Ruth’s former teammates, as well as Yankees from the 1948 season.

“Even the presence of other photographers to Ruth’s right lends a sense of importance to the scene,’’ Shieber said. “In short, Fein recognized the opportunity presented by this unique angle and took full advantage of it.”

He created a photo, in baseball parlance, of Ruthian proportions.

Scott Pitoniak is an author and nationally honored journalist residing in Penfield, N.Y. He has authored or co-authored more than 35 books, including “Remembrances of Swings Past: A Lifetime of Baseball Stories.”