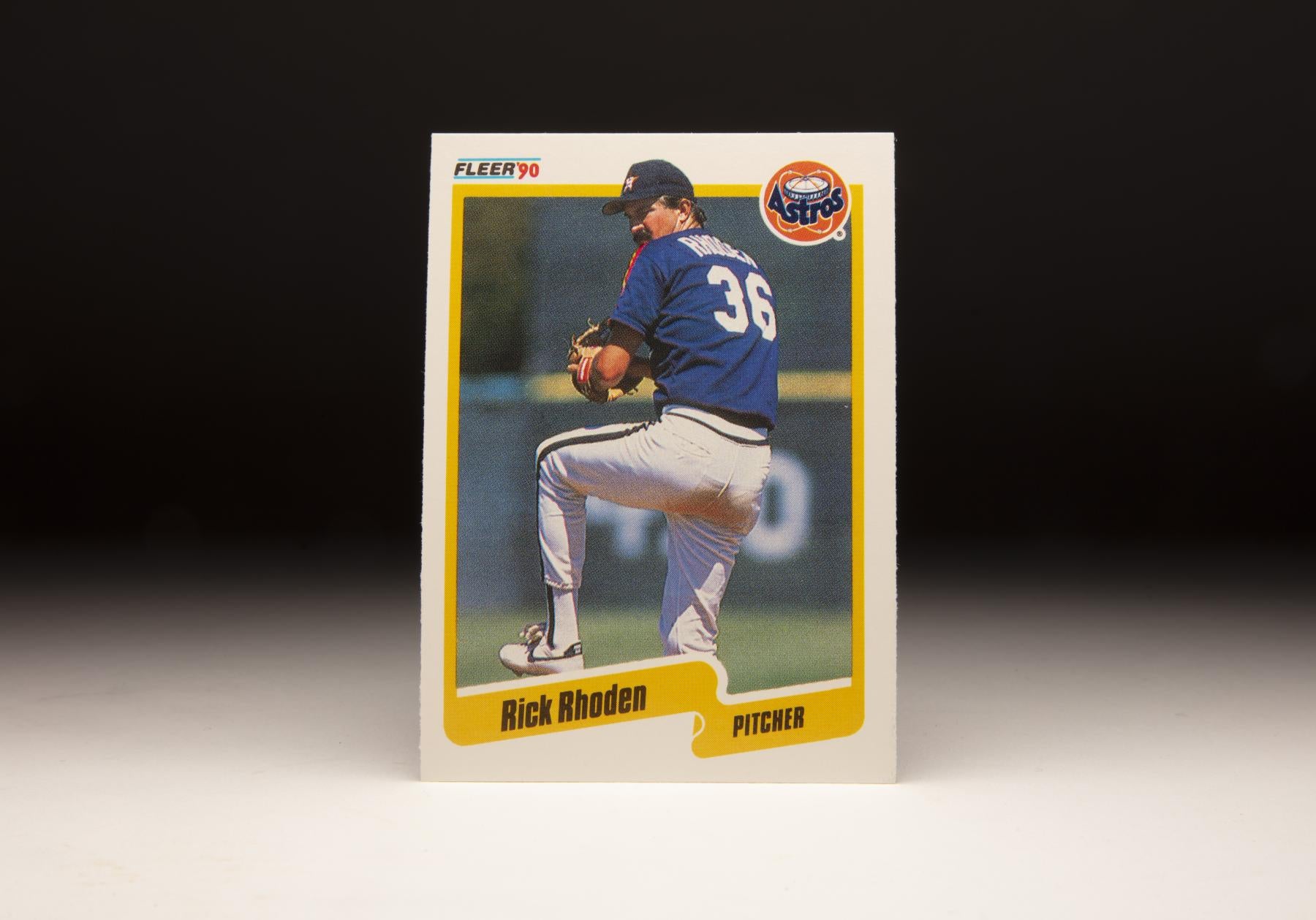

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Rick Rhoden

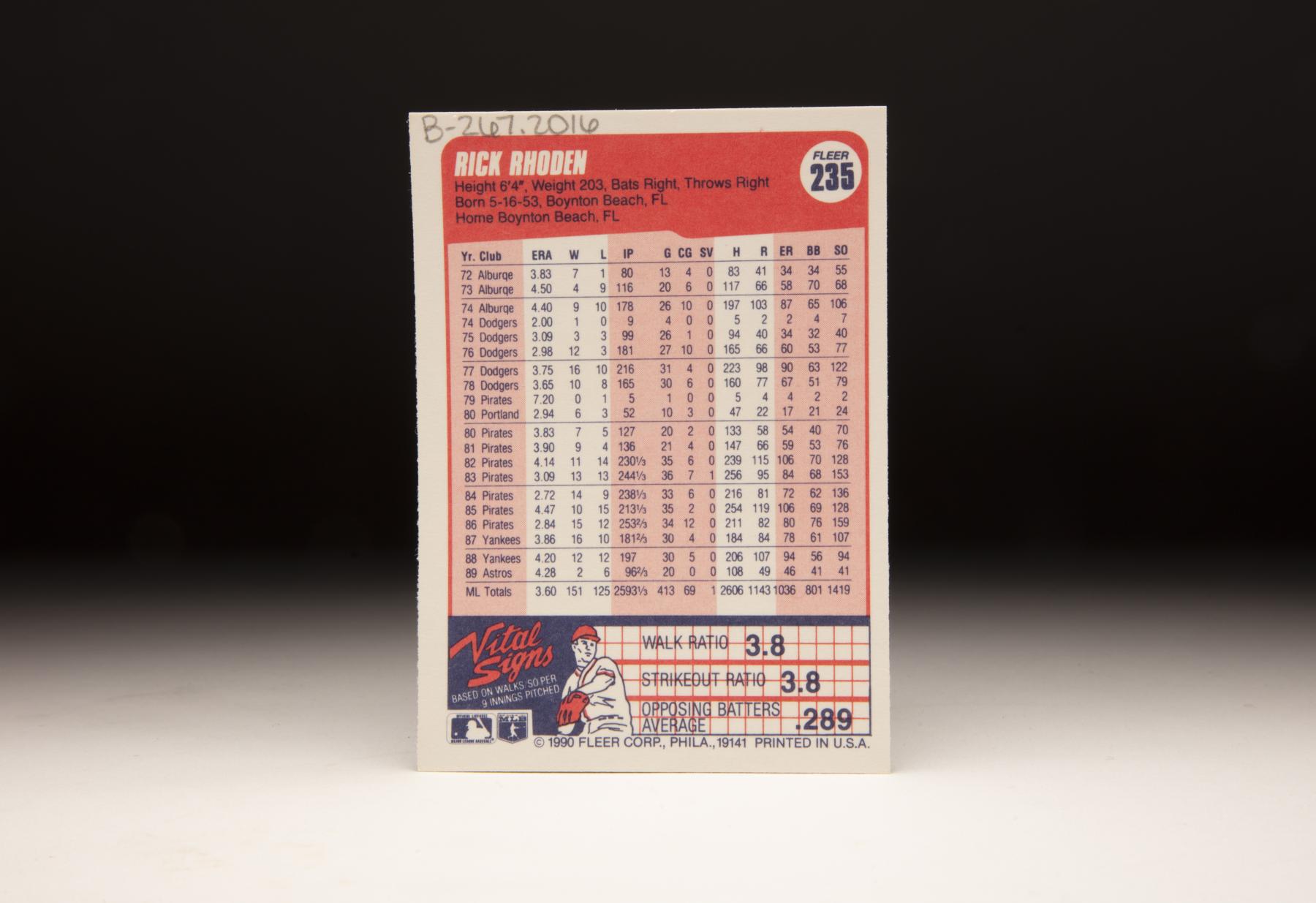

He won 151 big league games on the mound, making Rick Rhoden one of the most successful pitchers of his time.

But it was when he was swinging a club – whether on the diamond or the golf course – that made Rhoden a celebrity.

Richard Alan Rhoden was born May 16, 1953, in Boynton Beach, Fla. When he was eight, Rhoden was playing on a Slip ‘N Slide when he was cut on the right leg by a pair of rusty scissors. He soon developed osteomyelitis, a bone inflammation that usually afflicts children in the long bones of the leg and arm.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Doctors put Rhoden in a leg brace – which he wore for four years – and eventually removed part of his right knee.

“I had the leg brace and I adjusted,” Rhoden told the Associated Press in 1976 in a story that highlighted how Rhoden thought the injury was overblown in the press. “I still did everything I did before the accident except run.

“It’s no big thing. It’s nothing like, say, what Tommy John had to go through.”

At the time, John was just getting back to big league action after missing the entire 1975 season after undergoing what was then a revolutionary procedure to replace his ulnar collateral ligament. Nonetheless, Rhoden’s ability to overcome osteomyelitis made observers wonder if he could have been a position player as well as a pitcher – as his batting skills were that good.

Nurtured in baseball by his older brother Bill, who would pitch in college, Rhoden starred on the mound at Atlantic High School in Delray Beach, Fla. – striking out 20 batters in one eight-inning game – and was drafted by the Dodgers with the No. 20 overall pick in 1971. Sent to Class A Daytona Beach of the Florida State League, Rhoden went 4-6 in 11 starts while striking out 67 batters in 61 innings.

He started the 1972 season at Double-A El Paso and posted a 3.31 ERA over 87 innings before earning a promotion to Triple-A Albuquerque, where he went 7-1 with a 3.83 ERA over 13 starts and won two games in the playoffs. At 19 years old, Rhoden was younger than almost every batter he faced in Triple-A.

“I think moving up so fast helped me,” Rhoden told the Palm Beach Post just before Spring Training in 1973. “It made me a better player.”

Just like in 1972, the Dodgers brought Rhoden to their Spring Training camp in Vero Beach, Fla., in 1973. But when he was sent back to Albuquerque for more seasoning, Rhoden struggled – going 4-9 with a 4.50 ERA in 116 innings before missing the last month of the season with a sore elbow.

Rhoden began the 1974 season back in Albuquerque, and he fared little better than he did in ’73 – going 9-10 with a 4.40 ERA in 26 starts. But he stayed healthy all year and was summoned to the Dodgers during the summer, where he made his big league debut out of the bullpen against the Expos on July 5. He returned in September when rosters expanded, picking up his first win against the Padres on Sept. 22 with six innings of three-hit ball.

Los Angeles won the National League pennant before falling to Oakland in the World Series, but Rhoden was not on the postseason roster. Still, he had made a name for himself in the prospect-rich Dodgers farm system – and he won part of the Opening Day roster as a reliever in 1975.

In 26 games – including 11 starts – Rhoden was 3-3 with a 3.08 ERA as the Dodgers fell to second place in the NL West in 1975. Manager Walter Alston used a four-man rotation for most of the year: Andy Messersmith, Don Sutton, Doug Rau and Burt Hooton. But when Messersmith was declared a free agent by arbitrator Peter Seitz after the season, he signed with the Braves – leaving a spot in the rotation available for Rhoden.

In the NLCS vs. the Phillies, Lasorda lined up Tommy John, Don Sutton and Burt Hooton as his starters, sending Rhoden to the bullpen. Rhoden made his postseason debut in Game 3, working 4.1 scoreless innings in relief of Hooton as the Dodgers eventually rallied for a 6-5 win that eventually catapulted them to the World Series. Rhoden appeared in two games in relief in the Fall Classic against the Yankees, getting tagged with the loss in Game 1 when he allowed a 12th-inning walk-off single to Paul Blair before working seven innings in relief of Doug Rau in Game 4, allowing just two runs on one hit in a game New York won 4-2 en route to a six-game World Series victory.

“This place (Yankee Stadium) is really something,” Rhoden told the Rutland (Vt.) Daily Herald before Game 6 of the World Series. “The fans, the legend, the excitement – what a place to play a ballgame.”

A decade later, Rhoden would pull on the Yankee pinstripes and play in the Bronx.

The Dodgers returned their rotation intact in 1978, and Rhoden again served as the fifth starter. But as the season went on, rookie Bob Welch got more and more work in the rotation – with Rhoden often pitching out of the bullpen. John, Sutton, Hooton, Rau, Rhoden and Welch were the only pitchers to start games for the Dodgers that year – and Rhoden finished with a 10-8 record and 3.66 ERA in 164.2 innings.

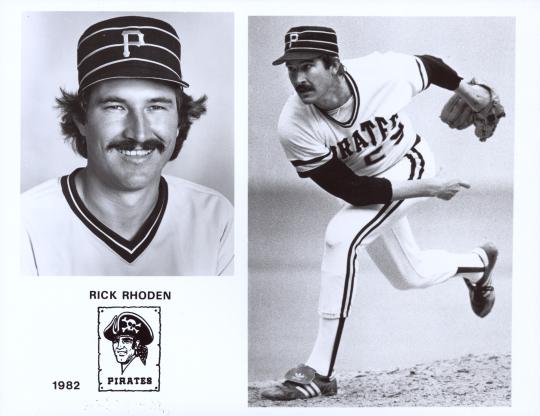

In 1981, Rhoden again got off to a fast start, winning his sixth game without a defeat by May 30. Passed over for the All-Star Game when play resumed in August following the strike, Rhoden finished with a 9-4 mark and 3.89 ERA.

“I always seem to get off to a good start,” Rhoden told the Palm Beach Post. “I don’t know why. I wish I knew what it was – maybe I could carry it over a little longer.”

Rhoden began the 1982 season in a much different manner, however, when his brother Bill died in a car crash April 14 in Charlotte, N.C. Rhoden pitched the following day against the Expos.

“It’s the toughest thing I’ve ever experienced in my life,” said Rhoden, who got a no-decision in a 4-3 Pirates win after allowing two earned runs over six innings. “It was my job to go out there and do the best I could and get my mind off it for a couple hours. I feel sorry for my folks more than anybody.”

Rhoden went 11-14 that season with a 4.14 ERA, working a career-best 230.1 innings. He then settled in as a staff workhorse, going 13-13 with a 3.09 ERA in 244.1 innings in 1983. And in 1984, Rhoden went 14-9 with a 2.72 ERA for a Pirates team that led the NL in ERA with a 3.11 mark but finished last in the NL with a record of 75-87.

Following the 1985 season, Rhoden asked the Pirates to trade him. But new general manager Syd Thrift could not find a suitable deal, and Rhoden rumors swirled throughout the 1986 campaign.

New manager Jim Leyland injected some life into the Pirates in 1986, however, and Rhoden responded by going 15-12 with a 2.84 ERA in 253.2 innings. Earning his second All-Star Game selection, Rhoden would finish fifth in the NL Cy Young Award voting.

With Rhoden’s value at an all-time high, Thift finally found his deal. With one year left on a contract that paid him a reported base salary $575,000, Rhoden – as a 10-and-5 player who could reject any trade – agreed to a deal that sent him to the Yankees along with Pat Clements and Cecilio Guante in exchange for Doug Drabek, Logan Easley and Brian Fisher.

It would be a bargain that would benefit the Pirates for years – mostly due to Drabek, who would go on to win the 1990 NL Cy Young Award.

“From the time I was hired, I said I would honor Rick Rhoden’s request to be traded to a contending ballclub if the deal was in the best interests of the Pittsburgh Pirates,” Thrift, who took over as GM following the 1985 season, told the AP as the trade details were being finalized. “I have fulfilled the only requirement Rick Rhoden ever asked of me.”

Rhoden and the Yankees quickly agreed to a new two-year deal with an option for 1989.

“If I get 35 starts and stay healthy all year,” Rhoden told the AP, “I don’t see any reason why I can’t win 20 games with a team like the Yankees.”

The Pirates, meanwhile, we’re facing their first season without their ace of the decade.

“We knew for a year that Rick Rhoden wanted to be traded,” Leyland told the AP after the deal. “But this is the first time we felt we were receiving quality in return.”

Rhoden put up his usual outstanding numbers in 1987, going 16-10 with a 3.86 ERA. But he struck out only 107 batters over 181.2 innings, indicating that at age 34 his durable arm was showing signs of age.

In 1988, Rhoden pitched a three-hit shutout over the defending World Series champion Twins on Opening Day. Then on June 11, Rhoden made history when he became the first pitcher since the advent of the designated hitter in 1973 to start a game in the DH role. Rhoden did not pitch against the Orioles that day – former Pirates teammate John Candelaria got the start for the Yankees – but went 0-for-1 with an RBI at the plate batting out of the No. 7 hole: Grounding out in the third inning against Jeff Ballard and hitting a sacrifice fly off Ballard in the fourth inning that scored Jay Buhner before being lifted for pinch hitter José Cruz in the fifth inning.

The unorthodox move by Yankees manager Billy Martin made headlines across the country.

“What do you think, I did this on a whim?” Martin told the Hartford Courant after being questioned by reporters about the strategy. “I think I know my personnel. (Rhoden) likes it, and it loosens the club up to see him up there hitting.”

It marked the first time a Yankees pitcher had come to bat since Ron Davis in 1980.

Rhoden continued to be a regular in the Yankees rotation but saw his ERA rise to 4.29 over 197 innings in 1988 as he finished with a record of 12-12. Then on Jan. 10, 1989, the Yankees traded Rhoden to the Astros in exchange for John Fishel and two minor leaguers.

“I like the National League better,” Rhoden said after the trade. “American League ballparks are too small and it’s a different game. The National League game is much faster with the (artificial) turf and more speed. In the AL, you just wait around until somebody hits a home run.”

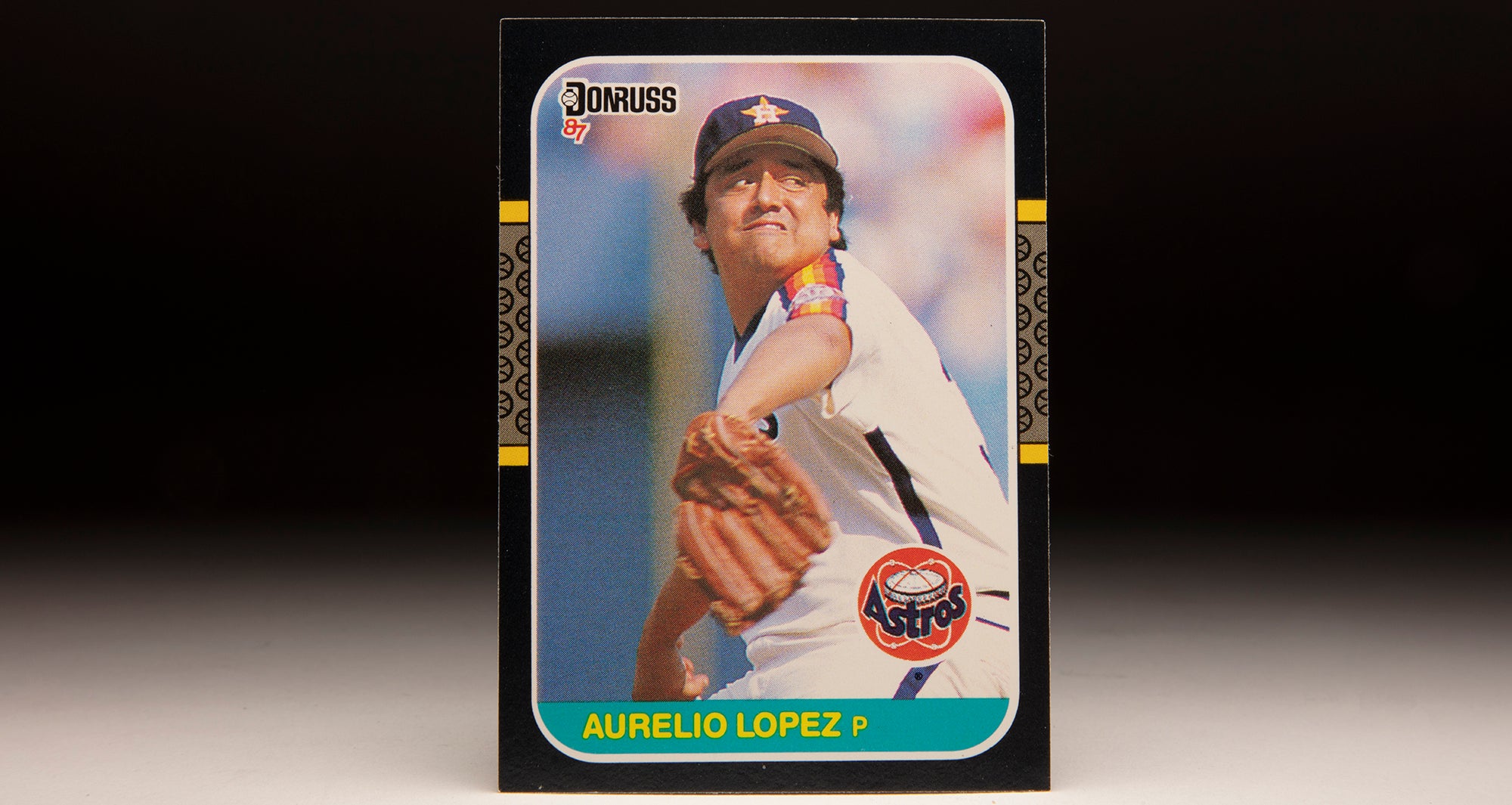

Rhoden appeared in seven of the Astros’ first 27 games in 1989, including six as a starter. But a rib injury sent him to the disabled list in early May, and he was ineffective upon his return in July. After posting a 2-6 record and 4.28 ERA over 97.1 innings, Rhoden became a free agent.

He stayed in shape as the start of Spring Training was delayed by a lockout but found no offers. But Rhoden was not out of the spotlight for long.

In 1991, Rhoden won the second edition of the American Century Championship, a celebrity golf tournament held annually on the shores of Lake Tahoe. Rhoden has won the tournament a record eight times, most recently in 2009. Rhoden also played regularly on the Champions Tour after turning 50 in 2003 and has taken home more than a quarter of a million dollars in prize money despite a back injury he suffered in an automobile crash.

“Before coming out on tour, I knew it would be difficult,” Rhoden said in 2006. “I was a better player before the (car crash).”

Over his 16 seasons in the big leagues, Rhoden went 151-125 with a 3.59 ERA and 1,419 strikeouts. At the plate, Rhoden hit .238 with 75 RBI and 38 doubles in 761 at-bats. And though he never won a Gold Glove Award, Rhoden posted a perfect 1.000 fielding percentage in exactly half of his MLB seasons, finishing with a career mark of .9894 – the best mark of any pitcher with at least 2,000 innings worked.

For Rhoden, it was a career on the diamond and links that would have seemed impossible when he was a child – or even early in his days with the Dodgers.

“I’d like to stay in baseball 10 or 12 years but I realize the average pitcher only makes it four-and-a-half to five years,” Rhoden told the AP in 1976. “I’ll face (a future career) when the time comes.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum