- Home

- Our Stories

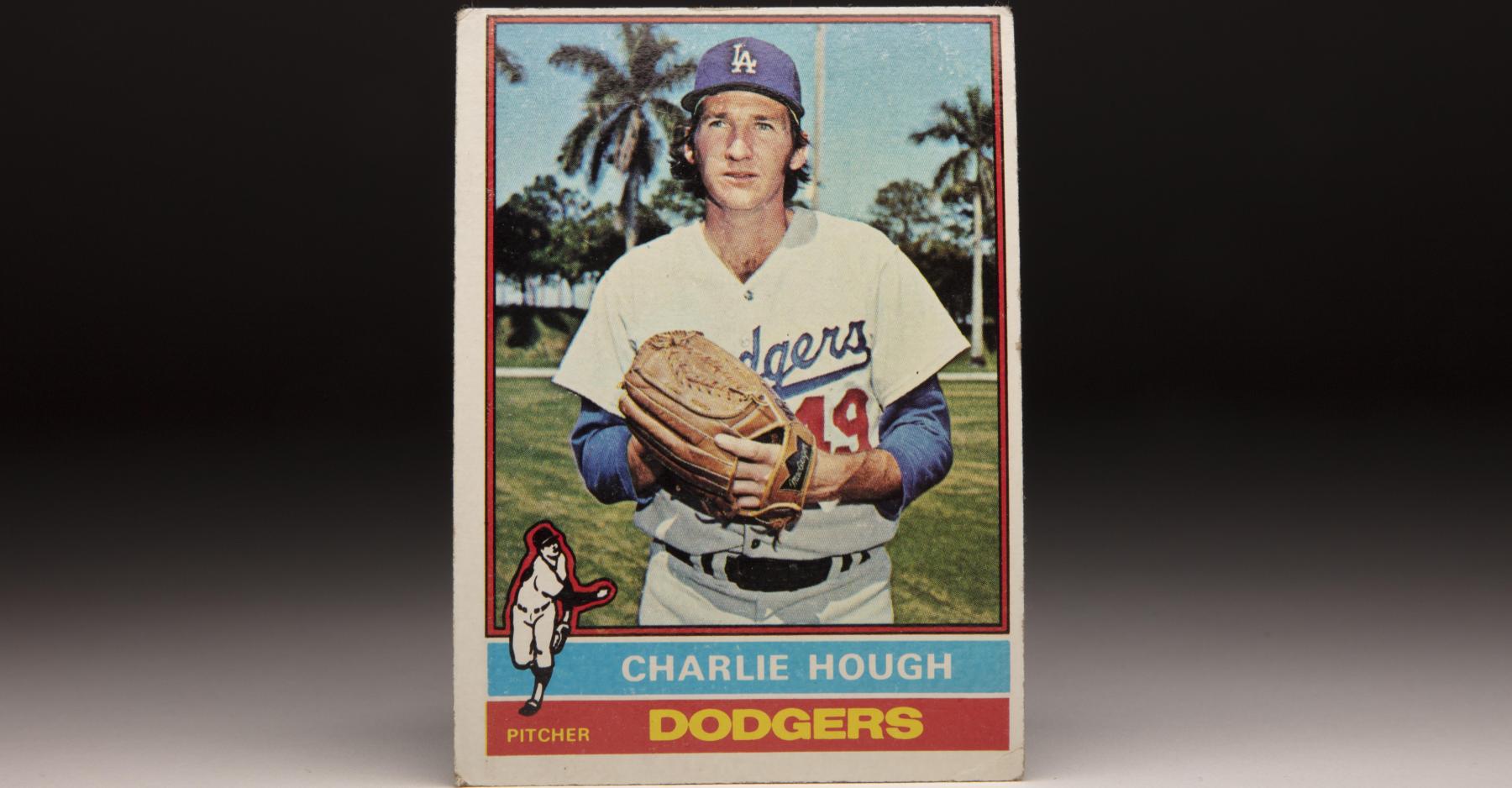

- #CardCorner: 1976 Topps Charlie Hough

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Charlie Hough

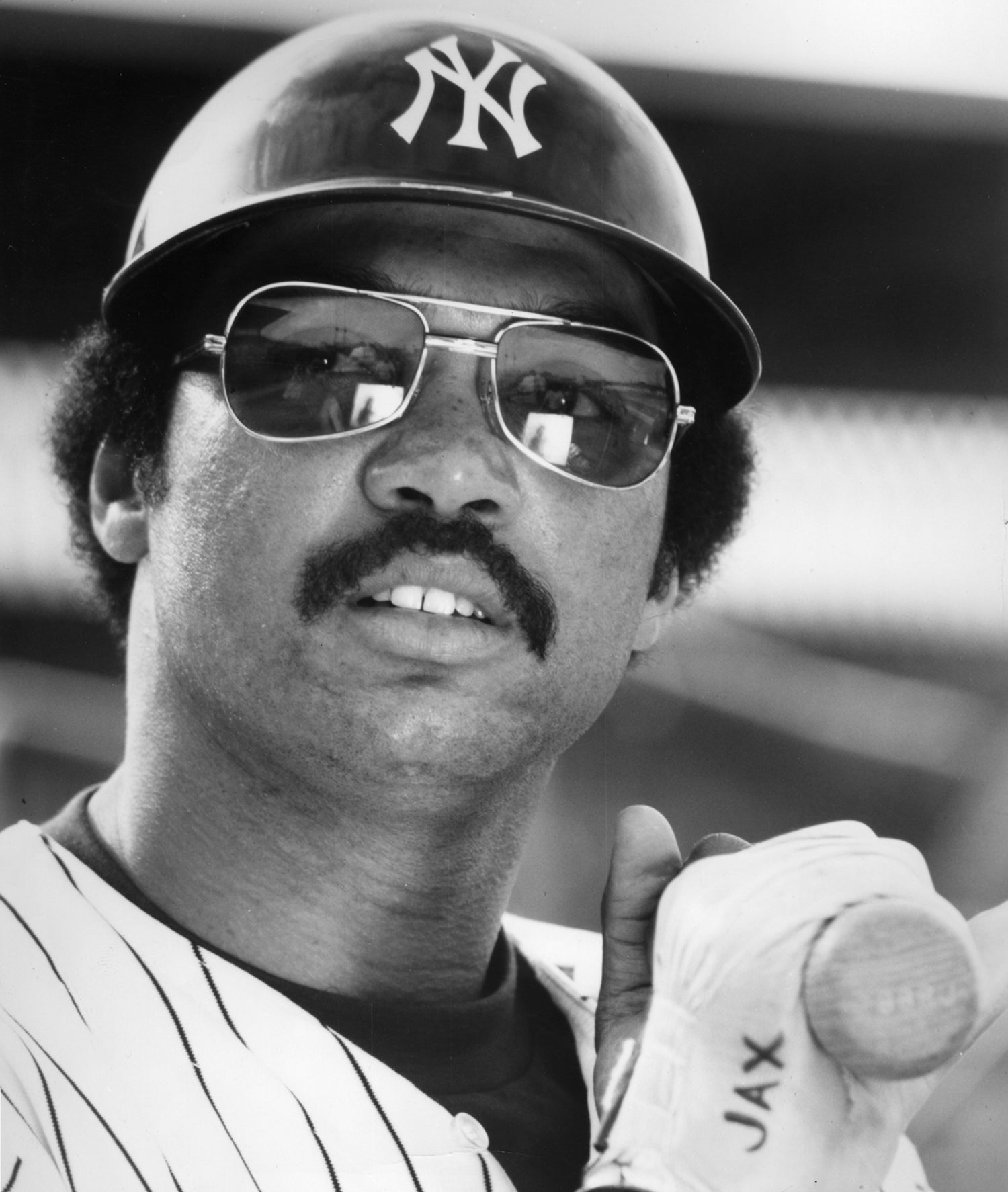

As Reggie Jackson circled the bases following his third home run in Game 6 of the 1977 World Series, Dodgers pitcher Charlie Hough grabbed a toss from home plate umpire John McSherry and prepared to throw another knuckleball to the next Yankees hitter.

At that point, the World Series was all but over – and Jackson being named Most Valuable Player was a mere formality.

Hough, however, made sure his career would be much more than a footnote in history. Because for the next 17 seasons, Hough would use his knuckler to become one of the most durable pitchers of the last half century.

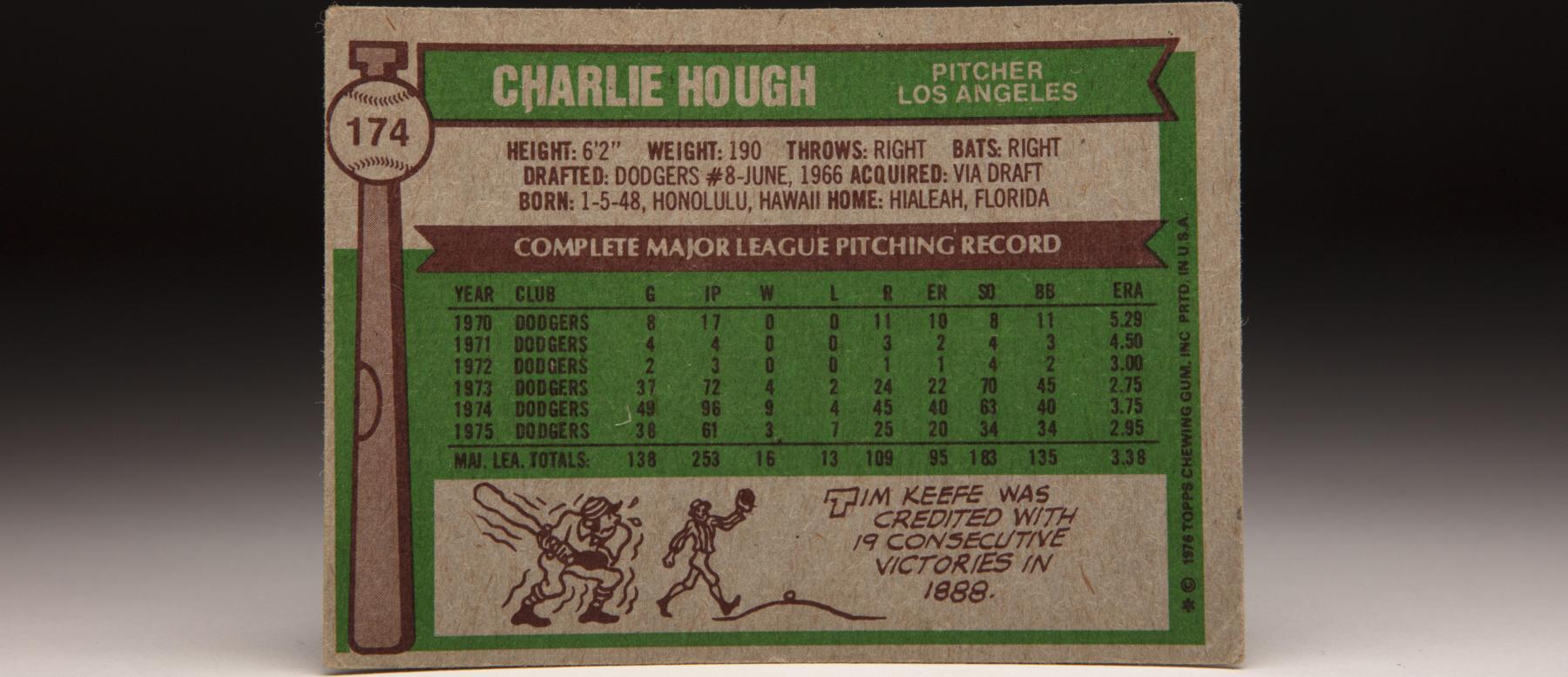

Born Jan. 5, 1948, in Honolulu and raised in Rhode Island and South Florida, Hough was the son of a minor leaguer who pushed his boys to be their best on the diamond – moving his family to the Miami area so his sons could play year-round. Richard Hough Jr., Charlie’s older brother, played a season with the Red Sox’s Class A team in Wellsville, N.Y., in 1964.

Charlie starred in basketball and baseball at Hialeah (Fla.) High School, earning All-City honors as a sophomore on the mound and then earning additional All-City notice as a junior in basketball. As a 15-year-old in 1963, Hough pitched Hialeah to the state American Legion baseball title.

A conventional pitcher at this point, Hough hurled a 16-strikeout, no-hit gem as a senior in 1966 and has his choice between playing basketball or baseball after he graduated.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“Charlie’s attitude is one of his greatest assets,” Hialeah coach Martin Frady told the Miami Herald. “And he’s made up his mind he wants to be a leader and use his talent. He has the potential to be a good pro baseball player.”

Drafted in the eighth round in 1966 by the Dodgers, Hough chose baseball and reported to Ogden of the Pioneer League, where he was 5-7 with a 4.76 ERA. But the next year at age 19, Hough went 14-4 with a 2.24 ERA at Class A Santa Barbara, earning a late-season promotion to Double-A Albuquerque.

Using a fastball/slider/curveball mix, Hough returned to Double-A in 1968 as one of the brightest pitching prospects in the Dodgers’ system. But even with future pitching guru Roger Craig serving as manager, Hough struggled – going 6-10 with a 3.94 ERA. He had hoped to earn a spot with Triple-A Spokane in 1969, but Hough was sent back to Albuquerque, where he was 10-9 with a 4.09 ERA in 26 starts.

Following the season, Spokane manager Tommy Lasorda and Dodgers roving pitching coach Goldie Holt suggested Hough – who was suffering from a sore arm – try the knuckleball. Hough experimented with it in the Arizona Instructional League before heading to Spokane for what would be the pivotal season of his career.

Through May, Hough – now a reliever – was 9-2 with a 0.68 ERA.

“It’s changed my career,” Hough told the Miami News. “My chances are much better of making the big leagues now. But I don’t know if I can recommend the knuckleball to anybody. It’s tough to control. You just have to hope you get it in the strike zone.”

Like most successful knuckleball pitchers, Hough devoted himself to the pitch. Once he demonstrated to hitters that he would throw the knuckleball at any point, Hough found success.

“It’s the best pitch in baseball,” Hough said.

Hough went 12-8 with 18 saves and a 1.95 ERA at Spokane in 1970. The Dodgers summoned him to the big leagues in August, and he notched saves in his first two appearances. He pitched in eight games down the stretch – but Dodgers manager Walter Alston was still not sold on giving Hough a permanent place on the roster.

In 1971 and 1972, Hough spent most of the time in Triple-A. He went 10-8 with 12 saves and a 3.92 ERA in 1971 with Spokane – but learned valuable lessons when future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm joined the team after he was released by the Braves. Wilhelm worked with Hough on the knuckleball, teaching Hough how to change speeds.

Hough then went back to Albuquerque (after the Dodgers relocated their Triple-A team to that city) in 1972, going 14-5 with a 2.38 ERA and 14 saves. He appeared in four big league games in the first month of the ’71 season before he was sent back to Triple-A, then was a September call-up in 1972.

“I think it takes an awful long time to get a good release point and a good feel it,” Hough told the Associated Press about the knuckleball. “If you change the grip in the smallest degree you get a spin – and you have no chance at all.”

Finally, in 1973, Alston put Hough on the Opening Day roster and stuck with him. By September, Hough was one of the mainstays of the Dodgers’ bullpen, finishing the season with a 4-2 record, five saves and a 2.76 ERA in 37 games.

“You just feel that the manager believes in you,” Hough told the Associated Press of his regular work. “Plus it helps when you believe in yourself.”

Hough and the Dodgers had no problem with confidence in 1974 as Los Angeles won 102 games to claim its first National League West title. Reliever Mike Marshall, acquired from the Expos after the 1973 season, won the NL Cy Young Award that year, appearing in a record 106 games while going 15-12 with 21 saves and a 2.42 ERA over an incredible 208.1 innings.

Hough was 9-4 with one save and a 3.75 ERA in 96 innings over 49 games. He made his postseason debut in Game 3 of the NLCS vs. Pittsburgh, relieving starter Doug Rau in the first inning and allowing two runs over 2.1 innings of work in the only game Los Angeles lost in the series. Then in the World Series, Hough entered Game 3 in the fifth inning with the Dodgers trailing 3-0. With the series tied at a game apiece, Hough blanked Oakland for two innings while recording four strikeouts.

Los Angeles rallied to cut the deficit to 3-2 but could not push the tying run across the plate in the ninth inning. The Athletics won the next two games – and Hough did not pitch again in the series. But Hough had finally cemented his status as a big leaguer.

“I’ll pitch until I’m 45 if they let me,” Hough told the Miami Herald in a prophetic moment.

Hough went 3-7 with four saves and a 2.95 ERA in 1975 as Alston went almost exclusively to a four-man rotation with Marshall as the primary reliever. But in 1976, Alston went back to a five-man rotation. And with Marshall feeling the effects of overwork, Hough became the main relief pitcher – appearing in 77 games while going 12-8 with 18 saves and a 2.21 ERA over 142.2 innings.

With only days remaining in the season, Alston resigned – turning the team over to Lasorda. Suddenly, Hough had one of his biggest supporters in the manager’s office.

“I wouldn’t trade one Charlie Hough for five Mike Marshalls,” Lasorda told the Miami Herald early in the 1977 season.

Lasorda led the Dodgers to the NL pennant in 1977 as Hough went 6-12 with a career-best 22 saves over 70 games. He allowed only three hits and one run over five innings of work in the World Series – but that one run was Jackson’s homer, which came on a low knuckleball but one that Jackson golfed into the deepest part of Yankee Stadium’s center field bleachers.

“It was low and away,” Hough told United Press International of the pitch. “But it didn’t move much.”

Such is the danger with a knuckleball, which takes no predestined path to home plate. With no spin, it is caught by air currents and goes wherever the wind blows. But when thrown for a strike, a knuckleball is almost impossible to hit solidly.

By this time in his career, Hough estimated that he threw the knuckler on 90 percent of his offerings.

“When I throw one, it will surprise you,” Hough told the Miami Herald of his fastball. “But unfortunately, how I throw it won’t.”

Hough transitioned out of the closer’s role in 1978 when the Dodgers signed hard-throwing lefty Terry Forster as a free agent. Hough appeared in 55 games that season, going 5-5 with seven saves as the Dodgers again won the NL pennant and again lost to the Yankees in the World Series. Hough appeared in one game in the NLCS against the Phillies and two more in the World Series, pitching the final 4.1 innings in Game 5 as the Dodgers lost 12-2.

Though Hough would go on to pitch 16 more years, it would be his last appearance in the postseason.

With injuries decimating their rotation in 1979, the Dodgers used Hough as a spot starter. He made 42 appearances – including 14 starts – and worked 151.1 innings, going 7-5 with a 4.76 ERA. For the first time since the 1972 campaign, Hough did not post a big league save.

Then on July 11, 1980, Hough – who was 1-3 with a 5.57 ERA over 19 games – was shipped to the Rangers in a cash transaction, reportedly in exchange for $20,000. Like so many knuckleballers, Hough had experienced a rough mid-career stretch. And like so many knuckleballers, Hough benefitted from a change of scenery.

“Yes, it’s a sad day for me,” Lasorda told the San Bernardino County Sun. “The guy and I have been together for 15 years. He’s helped me win pennants in the minor leagues, in winter ball and in Los Angeles. He’s a true Dodger. I love him like I do my own son.”

Hough worked as a starter and reliever with the Rangers the rest of the season but was much more effective, going 2-2 with a 3.96 ERA. With his contract expiring, Hough returned to the Rangers on a three-year deal worth a reported $450,000.

Hough worked in a swingman/long relief role in 1981, going 4-1 with a save and a 2.96 ERA over 82 innings. Then in 1982, the Rangers moved Hough into the starting rotation and named him their Opening Day starter.

“I figured I’d never get the chance again,” Hough told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I always wanted to start, but I was with a club (the Dodgers) that never really needed more starting pitching.”

Hough gave the Rangers exactly what they wanted – and more. He was 16-13 with a 3.95 ERA in 34 starts in 1982, then reeled off a six-year run where he averaged 16 wins, 35 starts, 256 innings and 167 strikeouts per season. Toward the end of the 1983 season, Hough threw three straight shutouts as part of a stretch where he did not allow a run over 36 innings.

He led the majors with 17 complete games in 1984, was named to his first All-Star Game in 1986 (he pitched 1.2 innings in the American League’s 3-2 win) and led the big leagues with 40 starts and 285.1 innings pitched in 1987.

Hough was the Rangers’ Opening Day starter each year from 1984-89 except for 1986, when he was injured after he broke his right pinkie finger while shaking hands with a friend.

The Rangers continued to extend Hough’s contract, taking him over the $1 million-per-season mark in 1990. But after going 10-13 in 1989 and 12-12 in 1990 – with ERAs over 4.00 in both seasons – the Rangers allowed Hough to leave as a free agent. He signed a one-year deal worth a reported $900,000 with the White Sox on Dec. 12, 1990.

Hough went 9-10 with a 4.02 ERA in 199.1 innings in 1991, then returned to the White Sox in 1992 and went 7-12 with a 3.93 ERA over 27 starts at age 44.

On Dec. 9, 1992, Hough signed one-year deal with the expansion Florida Marlins worth a reported $800,000.

“I was just talking to my brother, who lives in Miami Springs,” Hough told the Miami Herald. “I said: ‘Suppose we had said in high school that you could go down the Palmetto (Expressway) and play big league ball.’ It’s unbelievable. This will be like playing in the World Series, this year.”

Hough made his seventh Opening Day start in 1993, allowing three runs over six innings and picking up the win against the Dodgers in the Marlins first-ever game. Hough went 9-16 with a 4.27 ERA, making 34 starts and working 204.1 innings. He became just the second pitcher in history (Phil Niekro did it each year from 1984-86) to work at least 200 innings in his age-45 season.

Hough returned to the Marlins in 1994 and made his eighth-and-final Opening Day start but struggled during the season, going 5-9 with a 5.15 ERA in 21 starts in that strike-shortened campaign. He retired after the season and immediately underwent hip replacement surgery.

Healthy again in 1996, Hough returned to the Dodgers as a minor league instructor before working his way back to the big leagues in 1998 as the Dodgers pitching coach. He spent two seasons in that role before taking the same job with the Mets in 2001-02, then returned to the minors to work for another few seasons.

He finished his career with a record of 216-216, a 3.75 ERA over 858 games, 61 saves and 2,362 strikeouts.

Hough is one of only two Modern Era (post 1901) pitchers with at least 200 victories and a winning percentage of at or below .500. But unlike the other pitcher on that list – Bobo Newsom – Hough was also a topflight reliever who absorbed more than his share of hard-luck losses out of the bullpen.

All totaled, Hough rode the knuckleball to a 25-year big league career. Only two pitchers – Nolan Ryan and Tommy John – have pitched in more seasons.

“Sure, it would be nice to be able throw 95 miles an hour,” Hough told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “But I can’t – never could. So I had to find something else.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Devon White

#CardCorner: 1981 Donruss Iván de Jesus

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Eric Davis

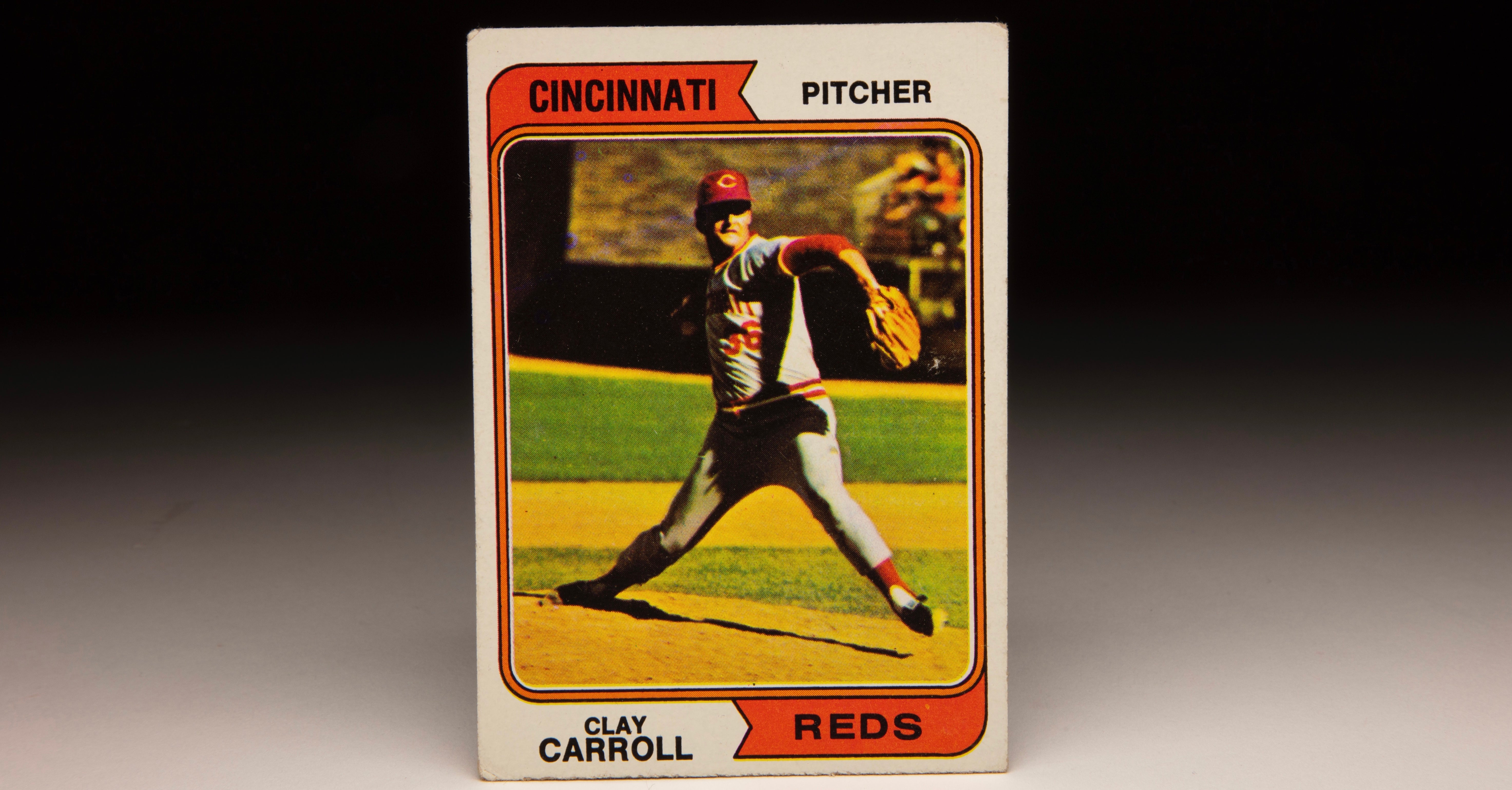

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Clay Carroll

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Devon White

#CardCorner: 1981 Donruss Iván de Jesus

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Eric Davis