- Home

- Our Stories

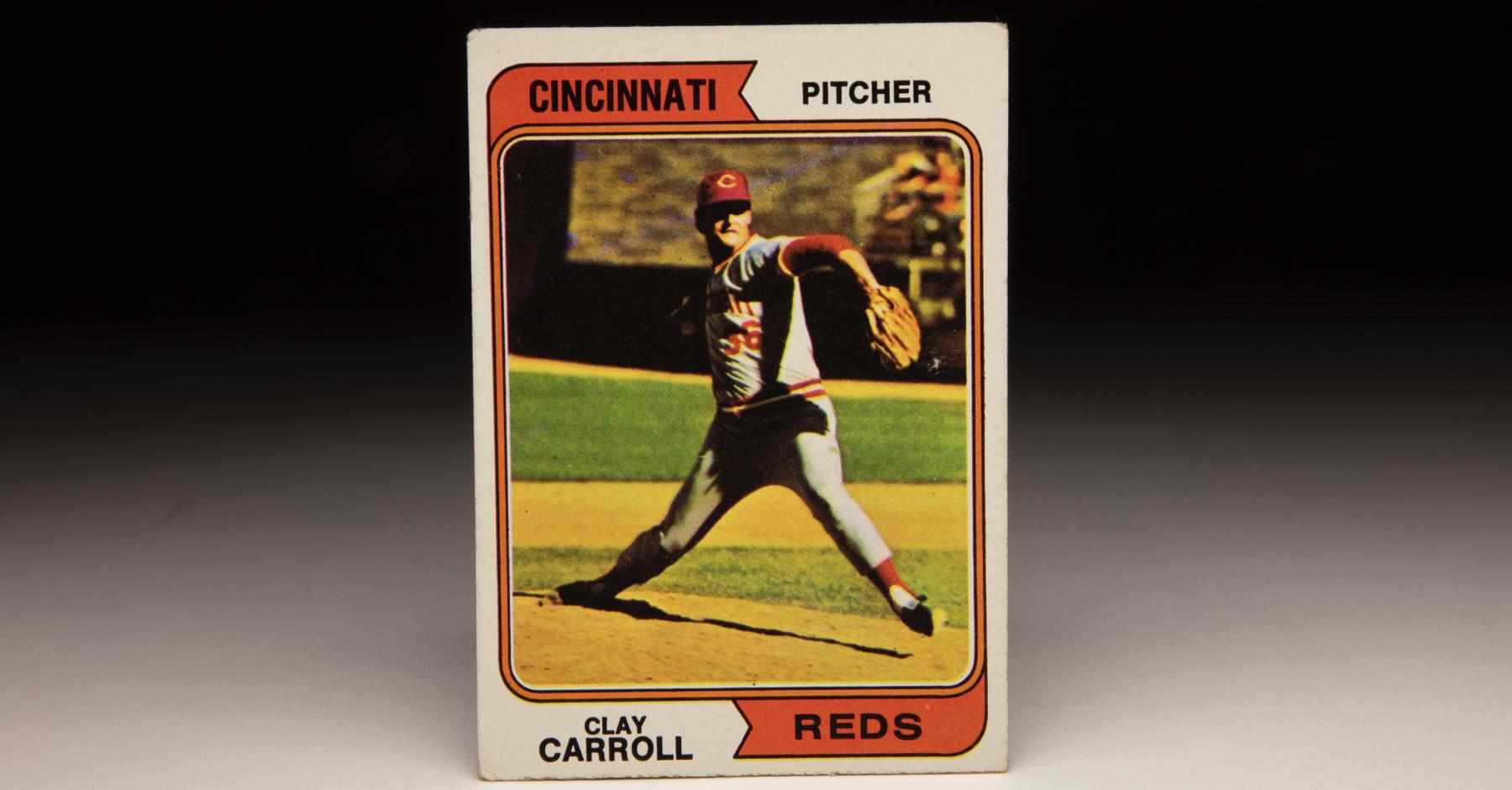

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Clay Carroll

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Clay Carroll

From 1970-75, the Cincinnati Reds played 19 World Series games – eight of which resulted in Cincinnati victories.

Clay Carroll pitched in five of those wins – earning two victories for himself, including Game 7 in 1975.

In a bullpen used often and well by manager Sparky Anderson, Carroll was a workhorse.

Carroll was born May 2, 1941, in Clanton, Ala., about 50 miles due south of Birmingham along what is now Interstate 65. Today it’s the heart of the Alabama peach crop, but Carroll grew up in a town dominated by textile mills.

By 1955, Carroll’s name began showing up regularly, thanks to his exploits on the baseball field, in Clanton’s newspaper: the Union-Banner. He starred on Little League, Babe Ruth League, Pony League and American Legion teams as well as at Chilton County High School, throwing a perfect game as a senior and putting together a streak of 27.2 scoreless innings.

On June 6, 1960, Carroll signed with the Milwaukee Braves for a modest $1,000 bonus. He began his pro career in 1961 with the Class D Davenport Braves of the Midwest League, where he was 7-10 with a 4.20 ERA in 122 innings.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

The next season, the Braves assigned Carroll to their Class C team in Boise, Idaho – which served as the organization’s showcase for its best young pitchers. Carroll went 14-7 and struck out 223 batters over 181 innings, then moved to Double-A Austin and Triple-A Denver in 1963 – posting a combined 11-11 record with a 4.30 ERA over 182 innings.

Carroll again split time between Austin and Denver in 1964, but this time was far more successful – going 10-8 with a 3.25 ERA. He was brought to Milwaukee with the September call-ups, making his big league debut on Sept. 2 against the Cardinals.

Over 11 appearances, which included two wins and a save, Carroll struck out 17 over 20.1 innings and worked to a 1.77 ERA.

Carroll had a strong Spring Training in 1965 and made a late bid for the Braves’ rotation before ultimately ending up back in the bullpen. But he showed uneven results throughout the season’s first two months, going 0-1 with a 4.70 ERA in 12 appearances before being sent to Triple-A in June.

The Braves had moved their Triple-A club to Atlanta in 1965 in advance of moving the big league team to the Deep South a year later, and Carroll fit right in – posting a 2.42 ERA over 13 starts with a hard-luck record of 3-6.

He returned to the Braves in August, and following the season set his sights on a rotation spot in 1966.

“I just want them to give me the ball and let me start,” Carroll told the Atlanta Constitution. “I can win in the National League.”

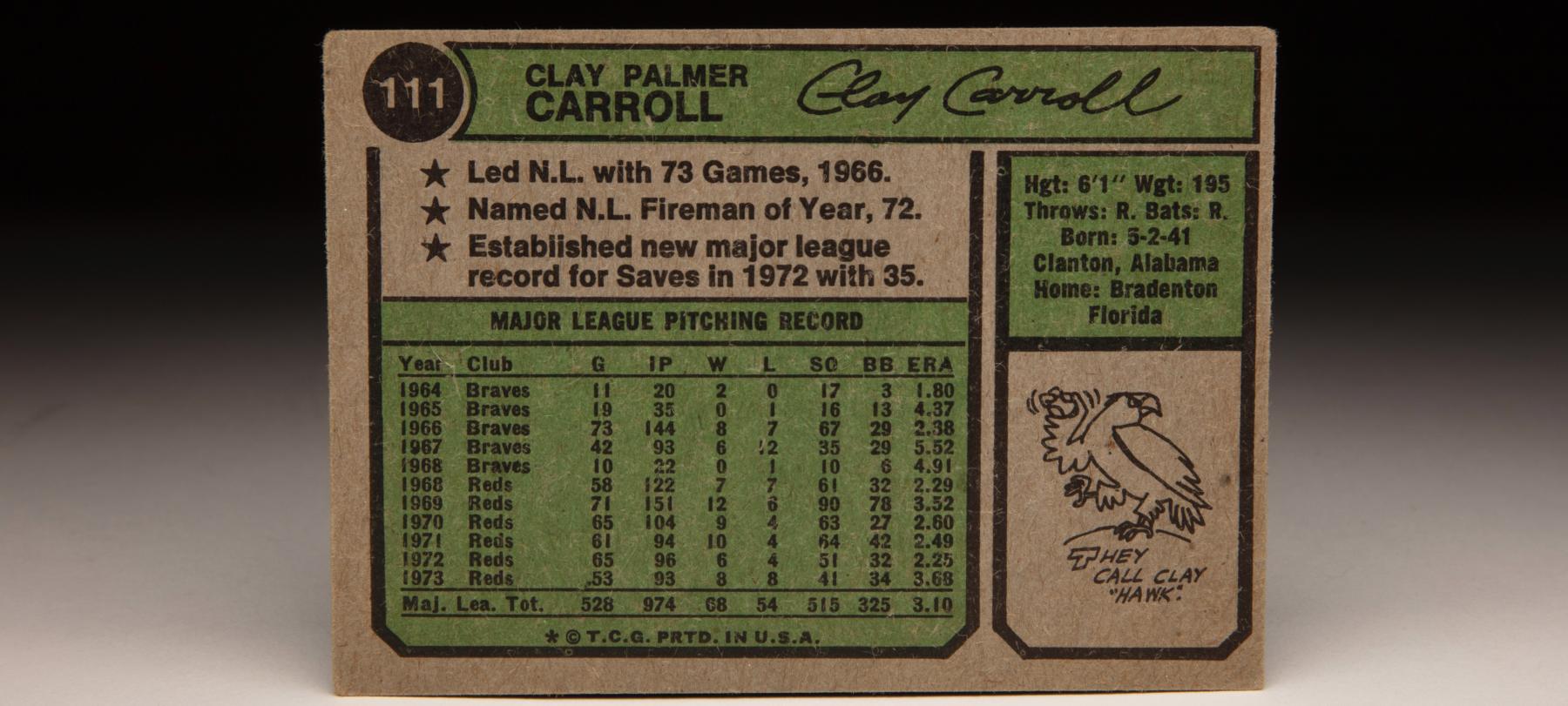

But Carroll, who had moved to Sarasota, Fla., and worked for a concrete company in the offseason to build up strength, once again found himself in the Braves bullpen. This time, however, he was effective from the start – sporting a sub-2.00 ERA as late as mid-June and finishing the season with a big league-leading 73 appearances, an 8-7 record, 11 saves and a 2.37 ERA over 144.1 innings.

His franchise games pitched record would stand for 14 years until Rick Camp pitched in 77 games in 1980.

“I wanted to be a starter,” Carroll told the Constitution in Spring Training of 1967. “But I wanted to stay on the club more. So when (Braves manager) Bobby Bragan told me to work in the bullpen, I became a relief pitcher.

“Mainly, I just want to pitch. The only thing I don’t like is not pitching.”

In 1967, however, Carroll was unable to find his top form for new manager Billy Hitchcock – who installed Carroll as the Braves’ closer but moved him into lower leverage role by May after Carroll allowed runs in seven of his first nine appearances. Carroll was sent to Triple-A Richmond in July to work out his issues and dominated minor league hitters. When he returned to the Braves, Carroll worked as a spot starter and reliever and finished the year with a 6-12 record and 5.52 ERA in 42 games.

Reporting to Spring Training in 1968 down about 20 pounds from his playing weight the year before, Carroll made the Opening Day roster but struggled in April and May – and found himself pitching in games where the Braves were losing, as Atlanta went 0-10 in the games Carroll pitched through June 5.

Then on June 11, the Braves and Reds pulled off a six-player deal, with Carroll, Tony Cloninger and Woody Woodward going to Cincinnati in exchange for Ted Davidson, Bob Johnson and Milt Pappas. The deal was primarily Cloninger for Pappas – but Carroll eventually became the player who tipped the scales of the deal in the Reds’ favor.

“It’s a gamble, but you just figure the possibilities and that’s it,” Braves general manager Paul Richards told the Constitution.

Cloninger, a former bonus baby, would win 27 games over four years with the Reds while battling arm injuries. Pappas spent the equivalent of two seasons with the Braves before being sold to the Cubs midway through the 1970 season.

Carroll, meanwhile, rediscovered his 1966 form and kept it for nearly a decade. After the trade, Carroll appeared in 58 games for the Reds, going 7-7 with 17 saves and a 2.29 ERA in 121.2 innings – impressing writers so much that he finished 25th in the NL Most Valuable Player voting that year.

Carroll was virtually untouchable in Spring Training games of 1969.

“I don’t think it’ll reverse once the seasons begins,” Carroll told the Cincinnati Enquirer.

He wasn’t unbeatable during the regular season but was still highly effective, going 12-6 with a 3.52 ERA and seven saves over 71 games that included 150.2 innings.

“I was really surprised with his velocity the first time I saw him cut loose,” Harvey Haddix, the Reds’ pitching coach, told the Enquirer. “He throws as hard as the good fastball pitchers.”

Then in 1970, Anderson took over the Reds and molded a young team into a powerhouse. Sharing the primary relief duties with Wayne Granger, Carroll was 9-4 with 16 saves and a 2.59 ERA in 65 games. He worked two games in the NLCS vs. Pittsburgh, picking up the save in Game 1 when Cincinnati broke open a scoreless game in the top of the 10th with three runs. Pitching in relief of starter Gary Nolan, Carroll retired the side in order in the bottom of the 10th with two strikeouts, including one when he caught Roberto Clemente looking.

Cincinnati swept the Pirates to advance to the World Series vs. Baltimore, and Carroll pitched 2.1 innings in both Game 1 and Game 2 – allowing no runs in both Reds’ losses. In Game 4, with Cincinnati in a 3-games-to-none hole, Carroll entered the game in the sixth inning with Cincinnati trailing 5-3. The Reds took a 6-5 lead in the eighth on Lee May’s three-run homer, and Carroll continued to blank Baltimore.

In the bottom of the ninth, Merv Rettenmund reached first on a throwing error charged to third baseman Tony Pérez. The throw pulled May off the first base bag, and when he tagged Rettenmund the ball popped out of his glove.

“Hawk (Carroll’s nickname), I’m sorry I dropped it,” May told Carroll. “It’s my fault. Pick me up.”

“When a man says something like that to you,” Carroll told the Dayton Daily News, “you’re gonna bust your gut to get the next guy out for him and yourself and the team.”

Carroll fanned Don Buford to end the game, giving the Reds their first win of the series. And though Baltimore went on to clinch the title in Game 5, Carroll had established himself as one of the game’s top relievers.

The Reds struggled to a 79-83 record in 1971, but Carroll remained effective – virtually duplicating his 1970 stats with a 10-4 record, 15 saves and 2.50 ERA in 61 games. He was named to the All-Star Game for the first time – fulfilling a goal that he openly talked about for several seasons.

In 1972, Anderson installed Carroll as his primary closer – and Carroll led the big leagues with 37 saves while going 6-4 with a 2.25 ERA in an NL-best 65 games. Carroll was again named to the All-Star roster and pitched the Reds to another NL West title. He appeared in two games in the NLCS vs. Pittsburgh – losing Game 3 but picking up the win in the decisive Game 5 when Cincinnati rallied for two runs in the bottom of the ninth.

Carroll worked five games in the World Series against the Athletics – a matchup that featured a record six one-run games. After working two scoreless innings in Game 1, Carroll picked up the save in Game 3 – a 1-0 win that featured eight scoreless innings by Reds starter Jack Billingham.

But the next day in Game 4, Carroll was tagged with the loss when the A’s rallied from a run behind with in the bottom of the ninth as Oakland manager leveraged three pinch hitters and two pinch runners into two runs. Two of the three hits off Carroll – including the game-winner by Angel Mangual – fell just out of the reach of Reds’ infielders.

Carroll bounced back in Game 5 with 1.2 scoreless innings in a game the Reds won 5-4 and retired three batters without a run scoring in Game 7. But the A’s won the deciding contest 3-2, launching their dynasty and leaving Cincinnati wondering what might have been.

In 1973, the Reds rewarded Carroll – who finished fifth in the NL Cy Young Award voting and 13th in the NL MVP race in 1972 – with an $18,500 raise to bring his salary to $67,000.

“I’m the highest-paid pitcher on the staff,” said Carroll, now one of the top paid relievers in the game after battling through a protracted holdout in 1972.

Anderson publicly stated his desire to use Carroll, who would turn 32 early in the 1973 campaign, in fewer games that season. Carroll finished the year with an 8-8 record and 14 saves over 53 games as the Reds again won the NL West title before losing to the Mets in the NLCS. Carroll worked three of the five games vs. New York, winning Game 4 with two perfect innings of relief as the Reds staved off elimination. But the Mets won 7-2 in Game 5 as Carroll was charged one run in two innings after he failed to stanch a New York rally in the fifth inning.

But Carroll continued to pitch well in 1974, going 12-5 with six saves and a 2.15 ERA in 100.2 innings over 57 games. The Reds ceded the NL West title to the Dodgers, but Carroll finished eighth in the NL Cy Young Award voting.

Carroll asked for a $100,000 contract in 1975 but settled for about $15,000 less. He delivered his usual outstanding work that season, going 7-5 with seven saves and a 2.62 ERA in 56 games for a Reds team that posted 108 victories and reclaimed the NL West crown. During that season, Carroll appeared in his 485th game with Cincinnati to surpass Joe Nuxhall’s team record for pitchers.

After sweeping Pittsburgh in the NLCS – Carroll pitched one scoreless inning in Game 3 – Cincinnati faced Boston in the World Series, with the Reds fighting a label as a team that could not win it all.

Carroll appeared in five games – with the highlight coming in Game 7 when, after the Reds tied the game at three in the top of the seventh, Anderson turned to his veteran reliever in the biggest of situations. Carroll responded by facing the minimum six batters over two innings, picking up the win when Joe Morgan’s RBI single scored Ken Griffey Sr. in the top of the ninth and Will McEnaney retired the Red Sox in order to end the game and the series.

But the good feelings did not last long for the Reds and Carroll. With McEnaney and Rawly Eastwick establishing themselves as reliable relievers – and Pedro Borbón already a favorite of Anderson – Carroll’s contract became expendable. He again asked for multi-year deal that would pay him $100,000 annually, and the Reds eventually worked out a trade with the White Sox, sending Carroll – who as a 10-and-5 player had the right to veto any trade – to Chicago in exchange for Rich Hinton and a minor leaguer on Dec. 12.

The White Sox quickly signed Carroll to a one-year deal worth a reported $100,000.

Carroll expressed regret at leaving the Reds but was glad to be reunited with Paul Richards, who was named the White Sox’s manager for 1976.

“He’ll do anything to win,” Carroll told the Bradenton (Fla.) Herald of Richards. “And he knows what type of pitcher I am.”

Richards, however, did not believe in the emerging bullpen concept. He moved closer Goose Gossage, who had a big league-leading 26 saves in 1975, into the rotation, where he was 9-17 in 1976. Carroll assumed the lead position in the bullpen but was used in a multi-inning role, working at least six innings in relief in three games over the season’s first three months.

Carroll was placed on the disabled list with a broken bone in his right hand on July 4 and returned a month later. But he was unable to help the White Sox avoid a last-place finish in the AL West, finishing the season with a 4-4 record and six saves with a 2.56 ERA in 77.1 innings over 29 games.

On March 23, 1977, the White Sox traded Carroll to the Cardinals in exchange for reliever Lerrin LaGrow. He pitched well for St. Louis, going 4-2 with four saves and a 2.50 ERA in 51 games before he was traded back to the White Sox, who were making a surprising push for the postseason under new manager Bob Lemon, on Aug. 31. But Carroll struggled back in Chicago, going 1-3 with one save and a 4.76 ERA over eight games as the White Sox finished third in the AL West with a record of 90-72.

With signs of age finally beginning to show, Carroll signed a minor league deal with the Pirates in 1978 and spent most of that season with Triple-A Columbus. He appeared in two late-season games for Pittsburgh before signing another minor league deal with Milwaukee for 1979. But after struggling in 12 outings with the Brewers’ Triple-A team in Vancouver, Carroll called it a career.

Carroll had three children with his first wife, Judy, got divorced and then married Frances Nowitzke on April 1, 1982 in Bradenton. Frederick Nowitzke, Frances’ son, served as Carroll’s best man.

On Nov. 16, 1985, Frederick Nowitzke shot and killed Frances and Clay Carroll’s 11-year-old son Bret and wounded Clay Carroll when he shot the former pitcher in the face at the family home in Bradenton. Frederick Nowitzke was convicted and sentenced to death – a conviction that was later overturned. A second trial resulted in Nowitzke being sentenced to life in prison.

Carroll, who was named to the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 1980, finished his big league career with a 96-73 record and 143 saves and a 2.94 ERA over 731 appearances.

He is one of only three pitchers in history – along with John Smoltz and Sparky Lyle– with at least 95 wins, 140 saves, 500 appearances and winning percentage of .550 or better.

“His greatest asset,” Reds pitching coach Harvey Haddix said of Carroll in 1969, “is his desire to pitch.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

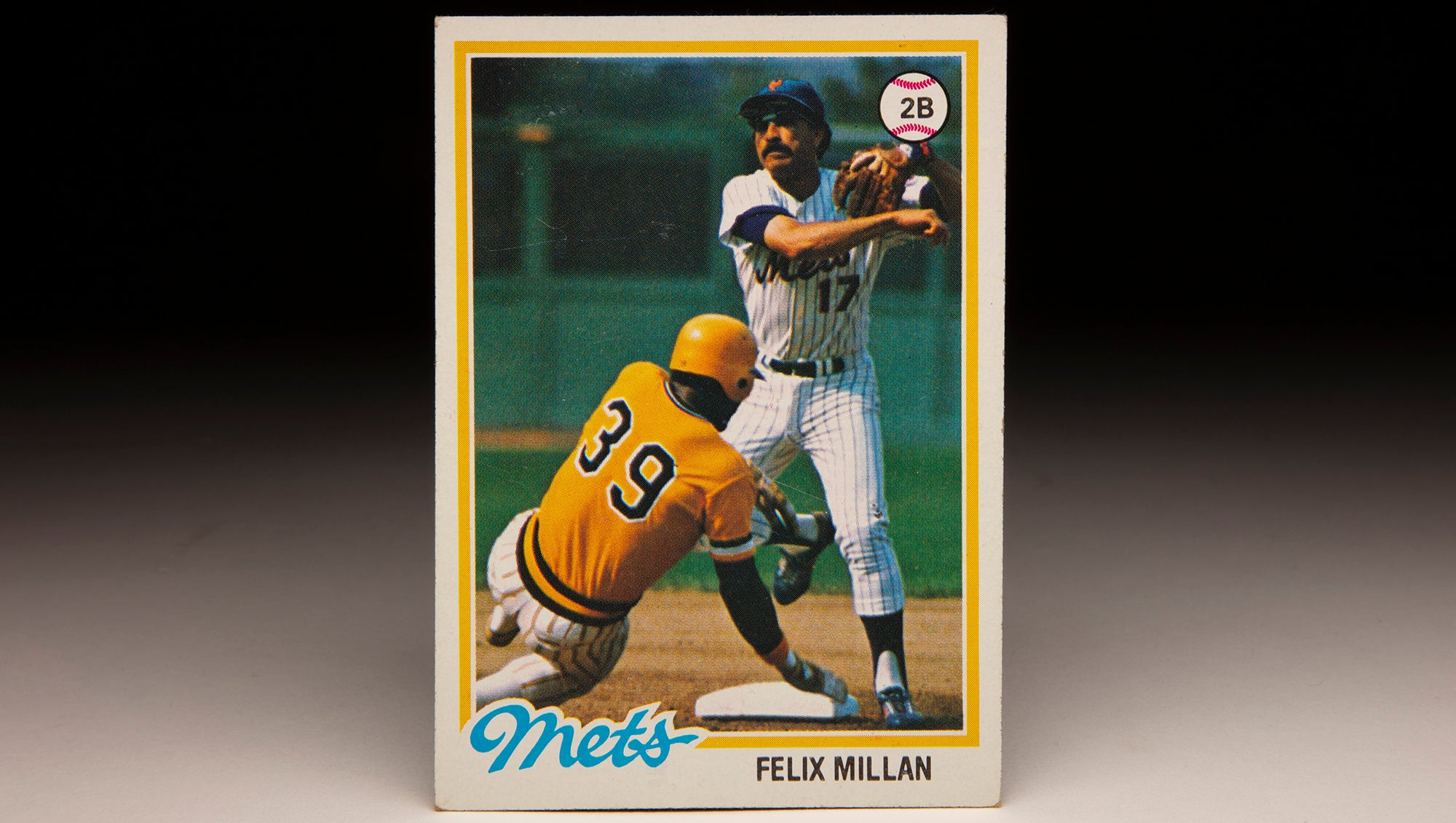

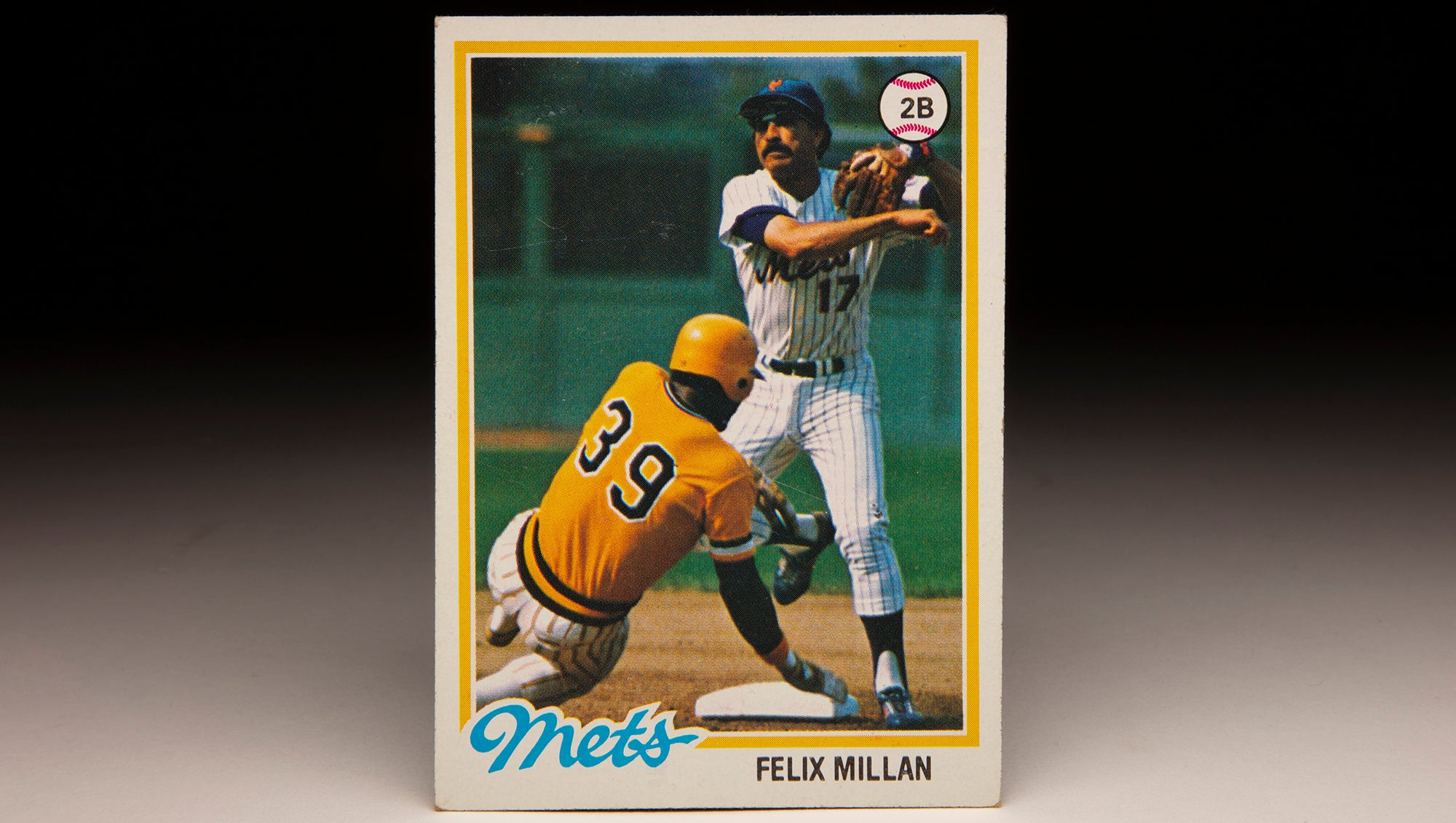

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Félix Millan

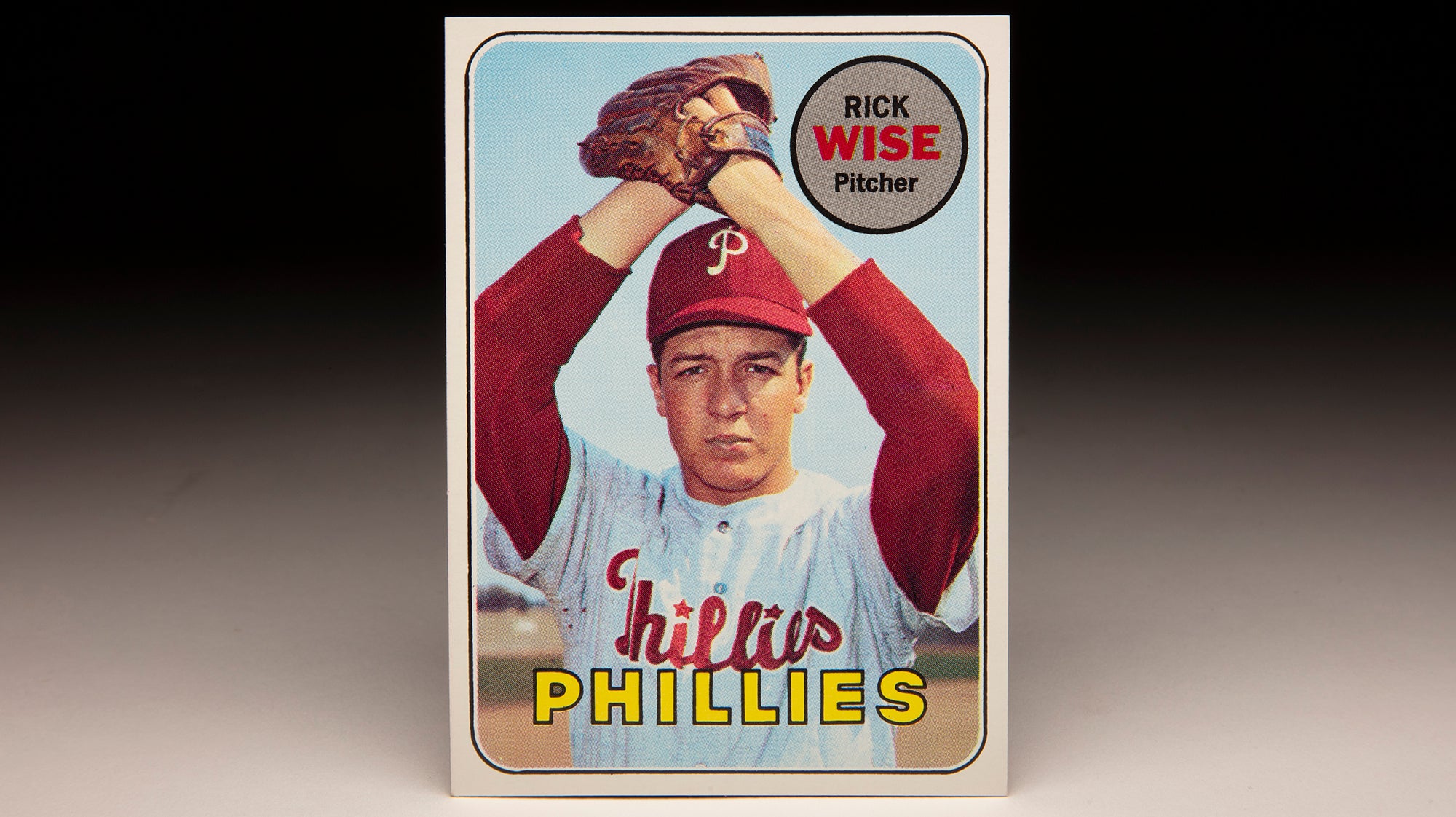

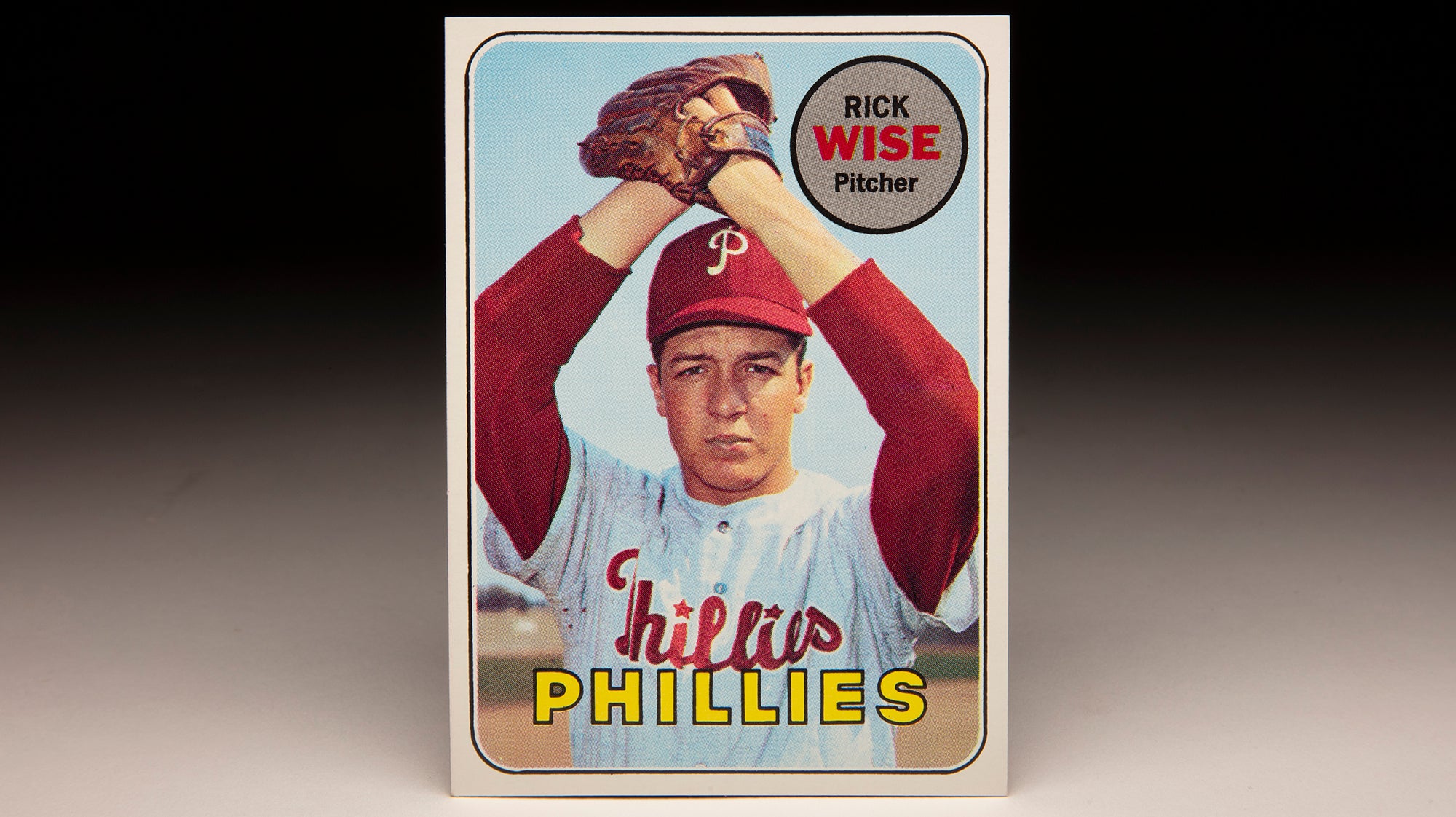

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Rick Wise

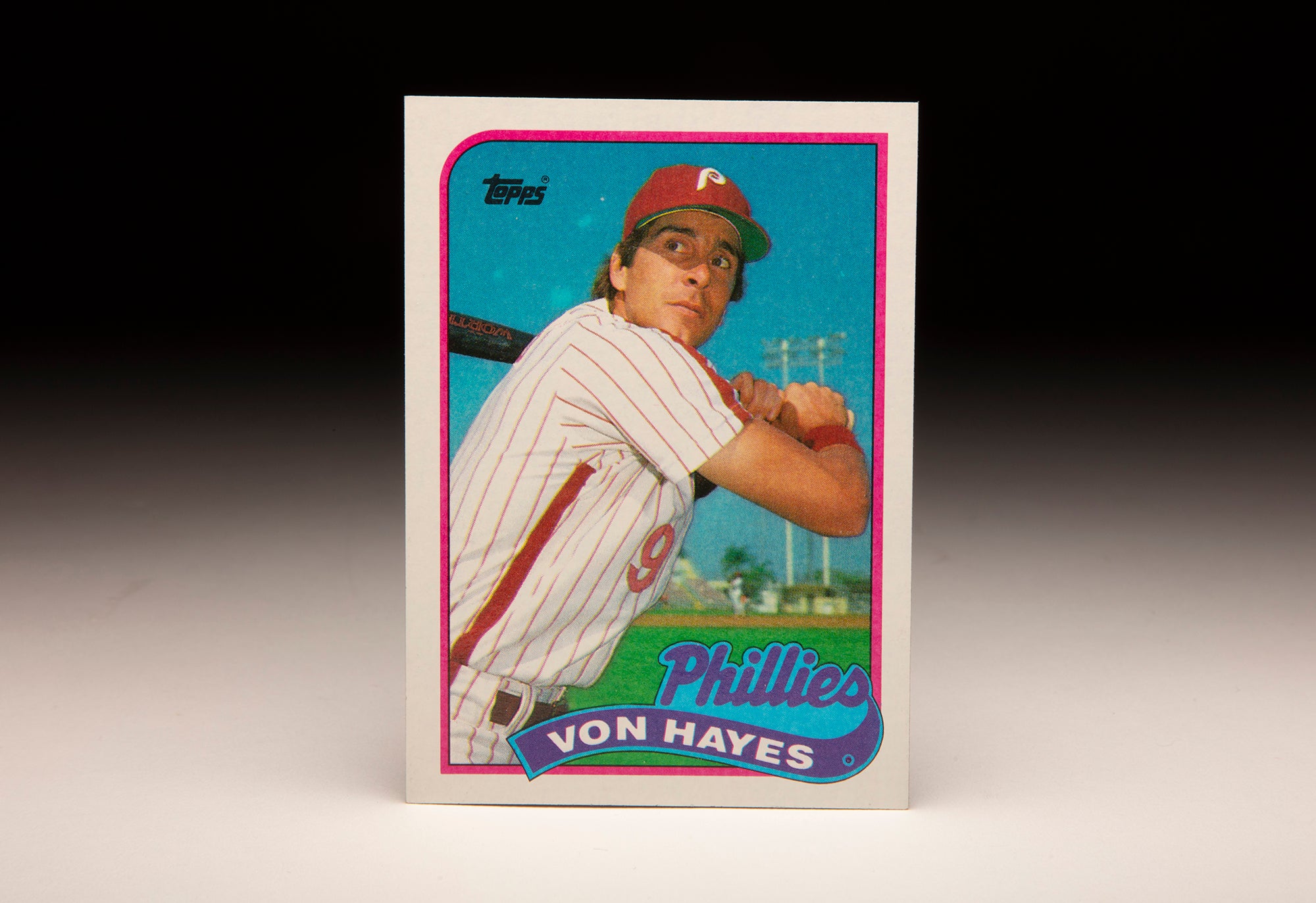

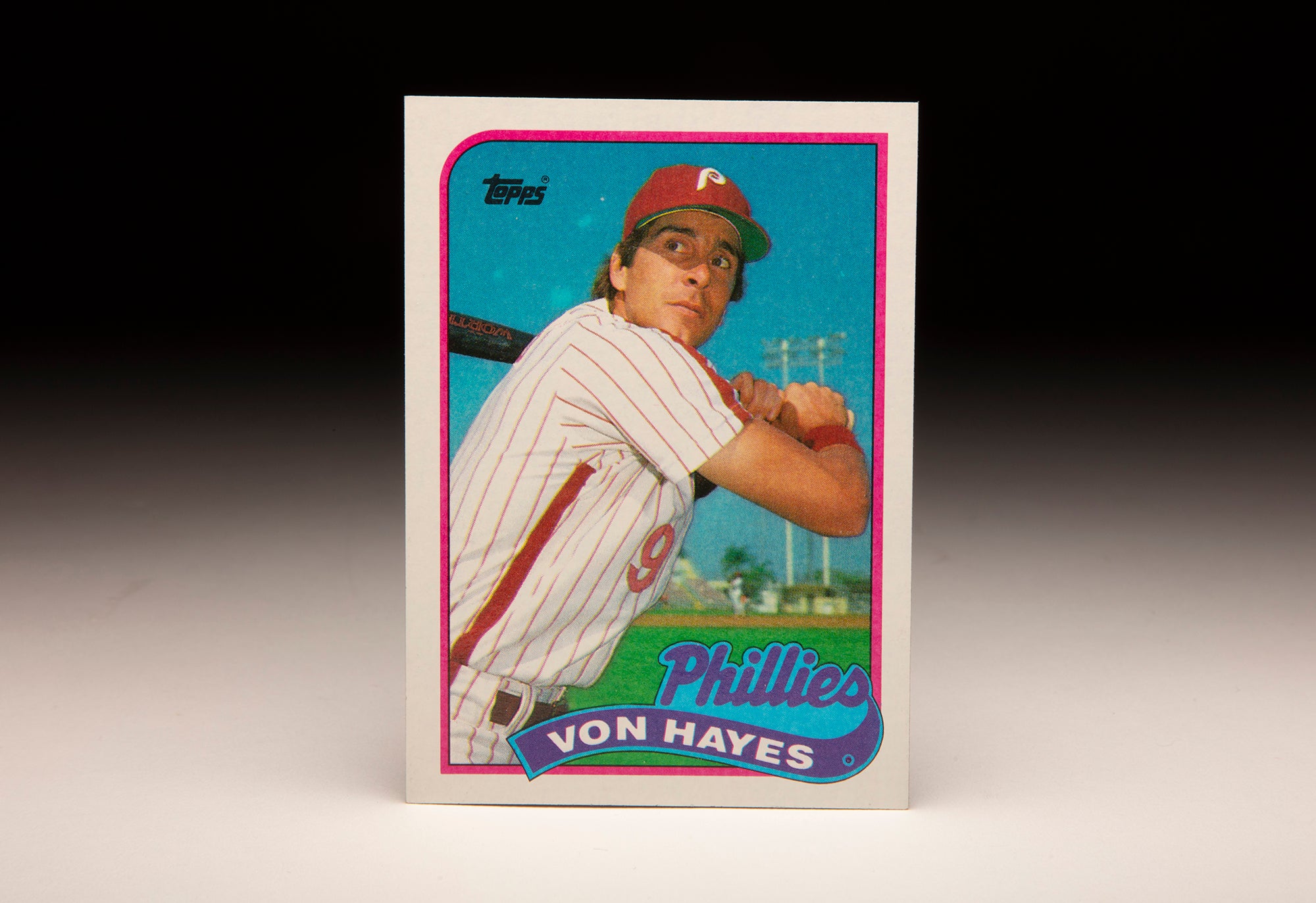

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Von Hayes

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Sam McDowell

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Félix Millan

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Rick Wise

#CardCorner: 1989 Topps Von Hayes