- Home

- Our Stories

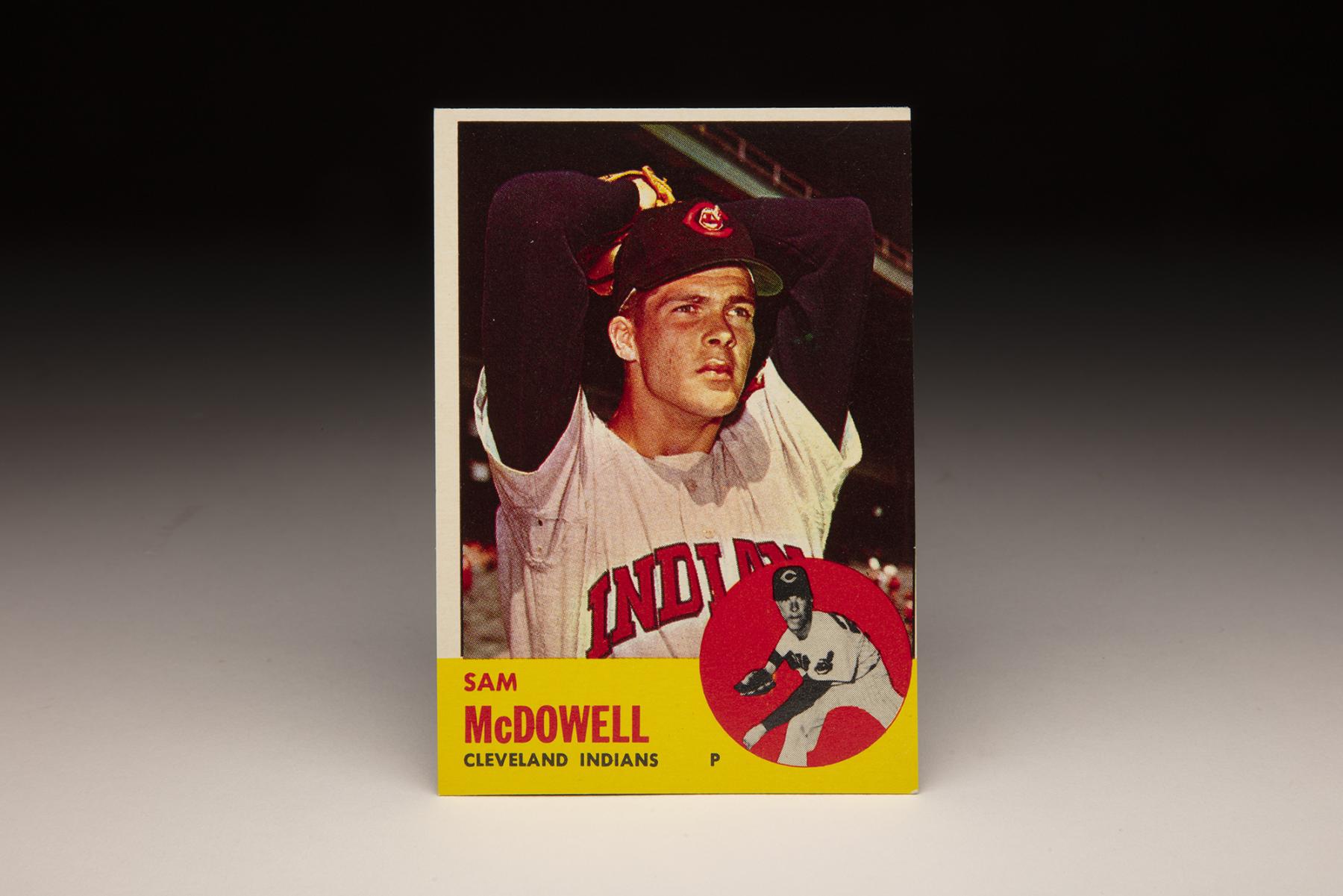

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Sam McDowell

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Sam McDowell

The numbers jump off the page on Sam McDowell’s entry in any record book: Two 300-strikeout seasons, five out of six years leading the American League in strikeouts and six All-Star Game selections in seven years.

Ultimately, alcoholism derailed a career that at one time seem destined for Cooperstown. But what McDowell left behind after 15 big league seasons can be summed up in a simple question: Did any left-hander ever throw harder than the man called Sudden Sam?

Born Samuel Edward McDowell on Sept. 21, 1942, in Pittsburgh, McDowell’s father, Thomas, was a member of the University of Pittsburgh football team in the 1930s. But Sam found a home on the diamond, and the lefty became a schoolboy legend on the mound. By the time he was a senior at Central Catholic High School in 1960, the 6-foot- 5 McDowell was credited with 40 no-hitters during his amateur career and regularly threw batting practice to his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field.

During his senior season, McDowell was 8-1 with 152 strikeouts in 63 innings and did not allow an earned run.

When McDowell graduated from high school on June 5, 1960, scouts from virtually every team in the big leagues were ready with offers. The Indians won the bidding war, signing McDowell to a bonus contract worth a reported $75,000 that made headlines in newspapers throughout the country.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

By June 21, McDowell was working out with the Indians at Cleveland Stadium.

“Sam has the fastball, but he also has a good curve,” Indians general manager Frank Lane told the Associated Press. “You find a lot of young pitchers with good fastballs. Many of them don’t have the loose wrist you need to snap off a curve.”

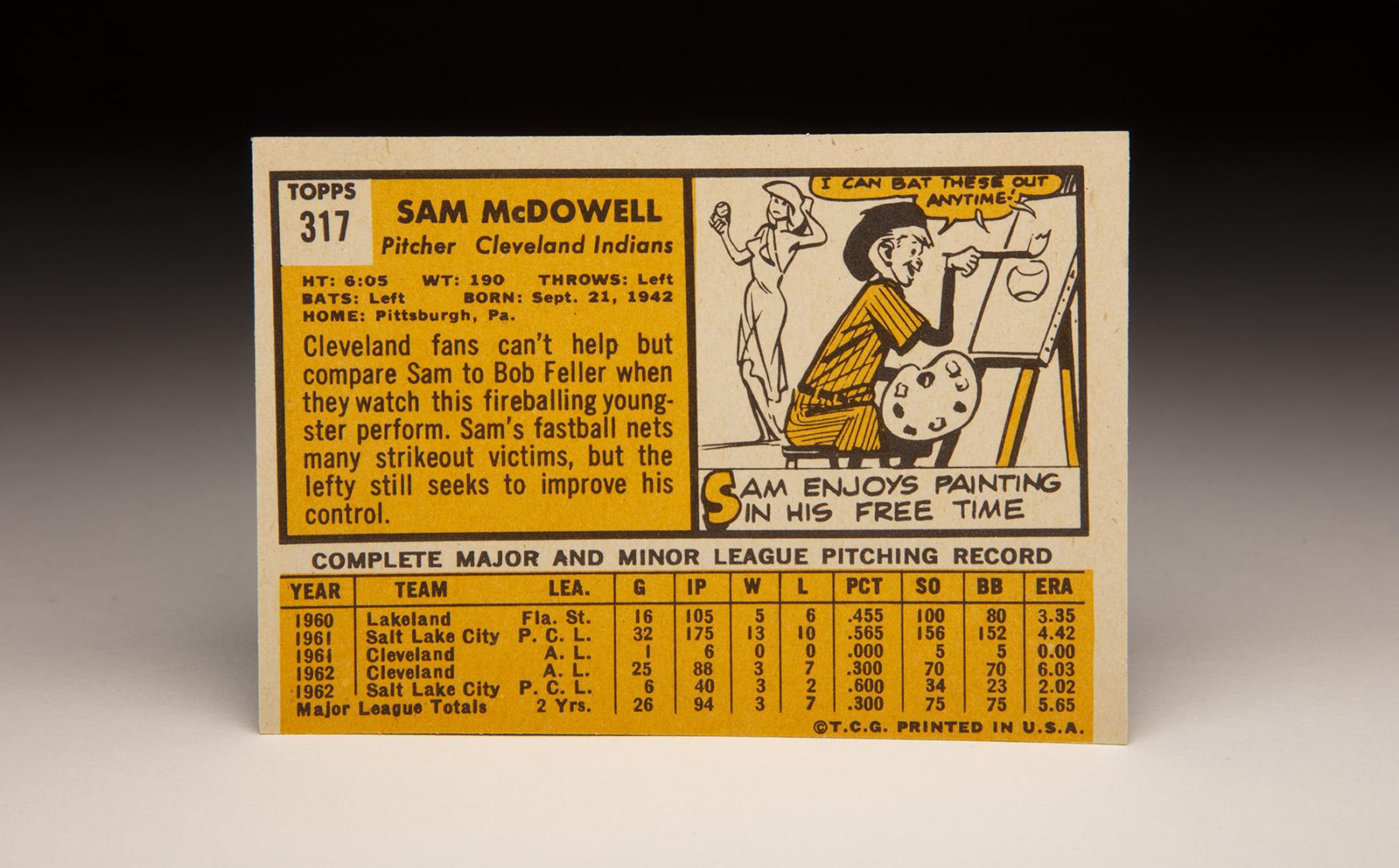

The Indians sent McDowell to Class D Lakeland of the Florida State League to begin his career, and McDowell went 5-6 with a 3.35 ERA over 16 starts, striking out 100 while walking 80 over 104.2 innings. He was also credited with an astounding 43 pickoffs, using a move to first base that he patterned after Warren Spahn’s.

Still just 18 years old, McDowell was soon invited to the prestigious Florida Winter Instructional League, where he dominated some of the best prospects in the game. Then in the spring of 1961, the Indians invited McDowell to their big league camp in Tucson, Ariz., where he was regularly compared to an Indians lefty phenom of the 1950s: Herb Score.

“I think Score was faster when he joined us,” Indians pitching coach Mel Harder told United Press International. “But McDowell has better control and a better curveball for this stage of development. In fact, McDowell’s curve is better than many pitchers with a few years of major league experience.”

Harder, a curveball specialist who won 223 games for the Indians over 20 seasons, was just one of many baseball veterans in awe of McDowell’s talent.

“If he doesn’t become one of the great pitchers,” said Indians director of player personnel Hoot Evers, “then I don’t know baseball talent.”

McDowell began the 1961 season at Triple-A Salt Lake City, where he was 13-10 with a 4.42 ERA over 175 innings, striking out 156 and walking 152 while harnessing his fastball. McDowell was six days short of his 19th birthday when the Indians introduced him to the big leagues in a start against the Twins, where McDowell worked 6.1 scoreless innings.

Gabe Paul, who replaced Lane as the Indians’ general manager in 1961, was widely expected to keep McDowell on Cleveland’s big league roster in 1962. But after an uneven spring and several rough starts in April and May, McDowell was returned to Triple-A in June before returning to Cleveland the following month.

He was 3-2 with a 2.03 ERA in 40 innings for the Bees, but struggled in Cleveland – posting a 3-7 record and 6.06 ERA over 25 appearances, including 13 starts.

McDowell bounced between the minors and the majors again in 1963, going 3-5 with a 4.85 ERA in 14 appearances for Cleveland. The in 1964, McDowell began the season with Triple-A Portland, where he went 8-0 with a 1.18 ERA in nine starts, striking out 102 batters in 76 innings. Over a three-start stretch, McDowell allowed a total of three hits – pitching a no-hitter, one-hitter and two-hitter.

“I found my control out at Portland,” McDowell told the New York Daily News. “No, we didn’t have a pitching coach there. I had to do it on my own.”

With nothing left to prove in the minors, McDowell was summoned back to Cleveland. This time, McDowell showed he was ready – striking out 14 White Sox batters in his first start on June 2 and shutting out the Athletics on four hits 10 days later.

“That was the turning point for me,” McDowell told the Tucson Citizen of his demotion to Portland to start the 1964 season. “I was determined that when I went to Portland I was going to pitch my way. I believe that you can’t tell a pitcher how to throw, when to throw and where to throw every pitch.”

By season’s end, McDowell was 11-6 with a 2.70 ERA, totaling 177 strikeouts in 173.1 innings to lead all big league pitchers with an average of 9.2 strikeouts per nine innings.

In 1965, McDowell – in his age-22 season – became just the fifth pitcher in the modern era (post 1900) to record a 300-strikeout season, whiffing 325 batters in 273 innings. McDowell was the first of those pitchers (a list which included Rube Waddell, Walter Johnson, Bob Feller and Sandy Koufax) to post a 300-strikeout season in fewer than 300 innings.

His mark of 10.7 strikeouts per nine innings set a new big league record, and McDowell finished the season with a mark of 17-11, an AL-best 2.18 ERA and his first All-Star Game berth.

“Hall of Famer,” teammate Ralph Terry told the Daily News of McDowell’s future. “If he doesn’t get hurt.”

But by this point, McDowell was already struggling with alcohol.

In 1966, McDowell began the season 4-0 and fanned 59 batters in his first six games, pitching back-to-back one-hitters April 25 and May 1. But after a 12-inning outing against the Orioles on May 6, McDowell began to experience arm problems. Moved to the bullpen following a May 21 start against the White Sox where he failed to retire any of the six batters he faced, McDowell bounced in and out of the rotation until his arm came around in July.

He finished the season with four complete games in his last eight starts, shutting out the Angels on four hits in the season’s penultimate game and posting a 9-8 mark with a 2.87 ERA for the year. Despite his arm issues, McDowell tied for the big league lead with five shutouts and led the AL with 225 strikeouts.

McDowell and the Indians struggled in 1967 as Cleveland finished eighth in the 10-team American League while McDowell was 13-15 with a 3.85 ERA, failing to lead the league in strikeouts or strikeouts per nine innings for the first time since 1963. The Indians responded by cutting his salary.

McDowell suffered facial lacerations that required stitches after a spring training car accident in 1968, but – after reporting to camp in the best shape of his pro career – took full advantage of the Year of the Pitcher, going 15-14 with a 1.81 ERA and a big league best 283 strikeouts. In 12 of McDowell’s 14 losses, the Indians scored one or zero runs – including five shutouts.

“I pitched well enough to win 20 games, but it’s not in the records,” McDowell told the Citizen in spring training of 1969. “This season I hope to see those 20 victories marked down.”

McDowell missed his goal by two wins that season, going 18-14 with a 2.94 ERA and once again leading the majors with 279 strikeouts. Then in 1970, McDowell hit the magic 20-win mark by going 20-12 with a 2.92 ERA, leading the AL with 305 innings pitched and topping all big league pitchers for the third straight season with 304 strikeouts.

McDowell joined Johnson, Koufax and Waddell as the only players to that point with multiple 300-strikeout seasons – and finished third in the AL Cy Young Award voting, a mere 10 points behind winner Jim Perry of the Twins. He set AL records for most strikeouts in two consecutive games (30), three consecutive games (40) and extended his AL record of games with double-digit strikeouts to 70.

McDowell held out of Spring Training in 1971, demanding a $100,000 salary from the Indians. But when negotiations hit an impasse, McDowell unhappily settled for $72,000.

“I intend to have another good year for the Indians,” McDowell told the Associated Press. “But that doesn’t mean I have to like working for them.”

But Commissioner Bowie Kuhn eventually ruled that McDowell’s contract contained performance incentives, a violation of MLB rules. Kuhn voided the contract and McDowell left the team after his July 27 start against the Angels, declaring that he should be considered a free agent because his contract was void. He rejoined the team in Cooperstown for the Indians’ appearance in the Aug. 9 Hall of Fame Game against the Cubs with a new deal that carried him through the 1972 season, but lost seven of his last eight decisions – finishing with a record of 13-17 and a 3.42 ERA. His 192 strikeouts were his fewest since 1964.

On Nov. 29 at the annual Winter Meetings, the Indians – who verbally agreed to trade McDowell at season’s end when he returned to the team – dealt their star lefty to the Giants for Gaylord Perry, who was four years older than McDowell, and shortstop prospect Frank Duffy.

“I honestly think the Giants gave up too much for me,” McDowell told United Press International. “But I intend to show them they didn’t make a mistake.

“I guarantee you the Giants are going to win the pennant next season. They’re gonna see a Sam McDowell they’ve never seen before.”

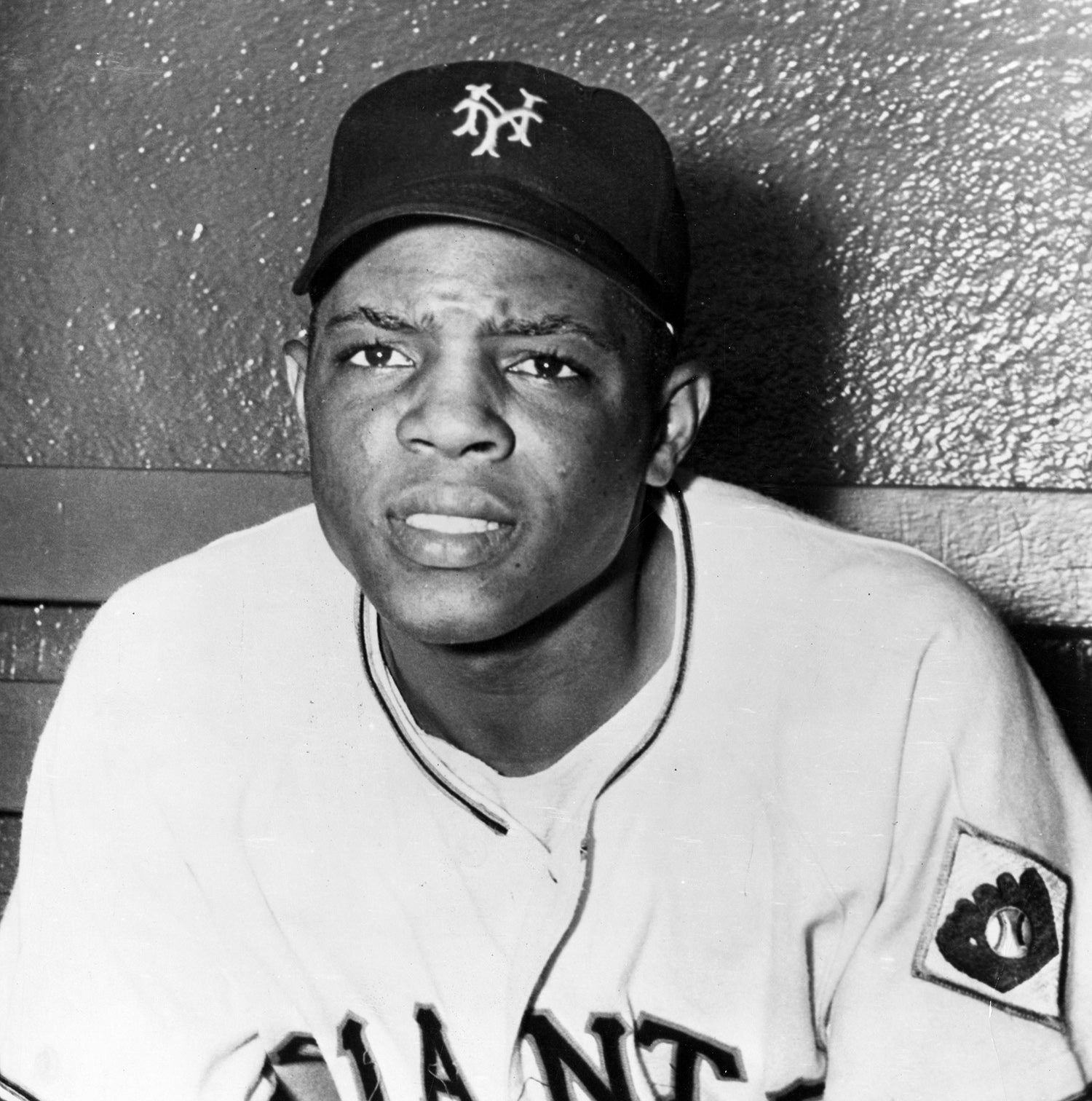

McDowell won his first five decisions in 1972 but the Giants were unable to recapture the momentum of 1971 that carried them to the NL West title. San Francisco found itself 15-31 entering June after trading the legendary Willie Mays to the Mets on May 11.

McDowell battled shoulder inflammation and was shut down in mid-July, making only two appearances in August before returning to the rotation in September. He finished the season with a 10-8 record and a 4.33 ERA over 164.1 innings, striking out 122.

“They really scared me this time,” McDowell told UPI about the doctors who advised that he could suffer permanent damage if he did not rest his arm. “Heck, I’ve played in pain before. But this time I guess it’s different.”

Perry, meanwhile, went 24-16 with a 1.92 ERA for the Indians, winning the AL Cy Young Award and earning a win, loss or save in each of his 41 appearances covering 342.2 innings.

McDowell struggled with back and neck pain in the spring of 1973 and contemplated retirement. But his health improved and Giants manager Charlie Fox – who had advocated for the Giants to acquire McDowell in the winter of 1971 – moved McDowell into the bullpen, using him as a spot starter and reliever.

McDowell’s drinking habits, however, had become more and more prevalent in the pages of Bay Area newspapers. Fox engaged in a personal feud with some of the reporters during the 1973 season, leading to unwanted publicity.

With McDowell making a reported $75,000 and the Giants surprisingly surging to the top of the NL West standings, San Francisco owner/general manager Horace Stoneham decided to sell high and shipped McDowell to the Yankees in a June 7 cash transaction.

“I don’t mean to sound boastful, but the Yankees are going to win the pennant because of Sam McDowell,” McDowell told Gannett News Service.

McDowell moved into the starting rotation in New York and won five of his first six decisions. But he didn’t win a game after July 20 and finished 5-8 with a 3.95 ERA over 16 appearances in New York as a late-season swoon left the Yankees at 80-82 and in fourth place in the AL East. For the year, McDowell was 6-10 with a 4.11 ERA.

Back problems plagued McDowell in 1974 and when healthy he was used sparingly by new Yankees skipper Bill Virdon. On Sept. 13 – with a 1-6 record and Virdon having begun to favor younger pitchers in McDowell’s former role – McDowell left the team.

“A month ago, I would have said he had a spot on this club next year,” Yankees pitching coach Whitey Ford told the Record in Hackensack, N.J. “But the way (Larry) Gura and (Mike) Wallace have pitched, I’d say no, he wouldn’t have stuck next year.”

At that point, McDowell had pitched 13 seasons in the big leagues and accumulated 2,424 strikeouts – a total topped by only nine other pitchers in history.

McDowell received an invitation to Spring Training with the Pirates in 1975 and pitched his way onto the roster as a bullpen arm. He was 2-1 with a 2.86 ERA in 14 games when Pittsburgh released him on June 26, ending his big league career.

For the next five years, McDowell struggled with alcohol, losing his family and sinking into almost a quarter of a million dollars in debt. In 1980, in his parents’ house in Pittsburgh, McDowell hit bottom.

“You beat me! You beat me!” McDowell said he cried out on the night he chose to seek help.

Checking into Pittsburgh’s Gateway Rehabilitation Center, McDowell got clean and eventually earned degrees in sports psychology and addition from the University of Pittsburgh. By 1984, he was back working in baseball with the Texas Rangers, who hired McDowell to establish a sports psychology program. He also worked tirelessly for the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), helping former players.

He would go on to form the City of Legends in Clermont, Fla., a retirement community for athletes.

In his 14 years in the big leagues, McDowell was 141-134 with a 3.17 ERA and 2,453 strikeouts, leading the AL five times. Since his debut in 1961, only Nolan Ryan (10) and Randy Johnson (nine) have led their league in strikeouts more times than McDowell.

“There’s no need for redemption,” McDowell told the Orlando Sentinel in 2003 as he worked on completing the City of Legends. “Addiction is a disease.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

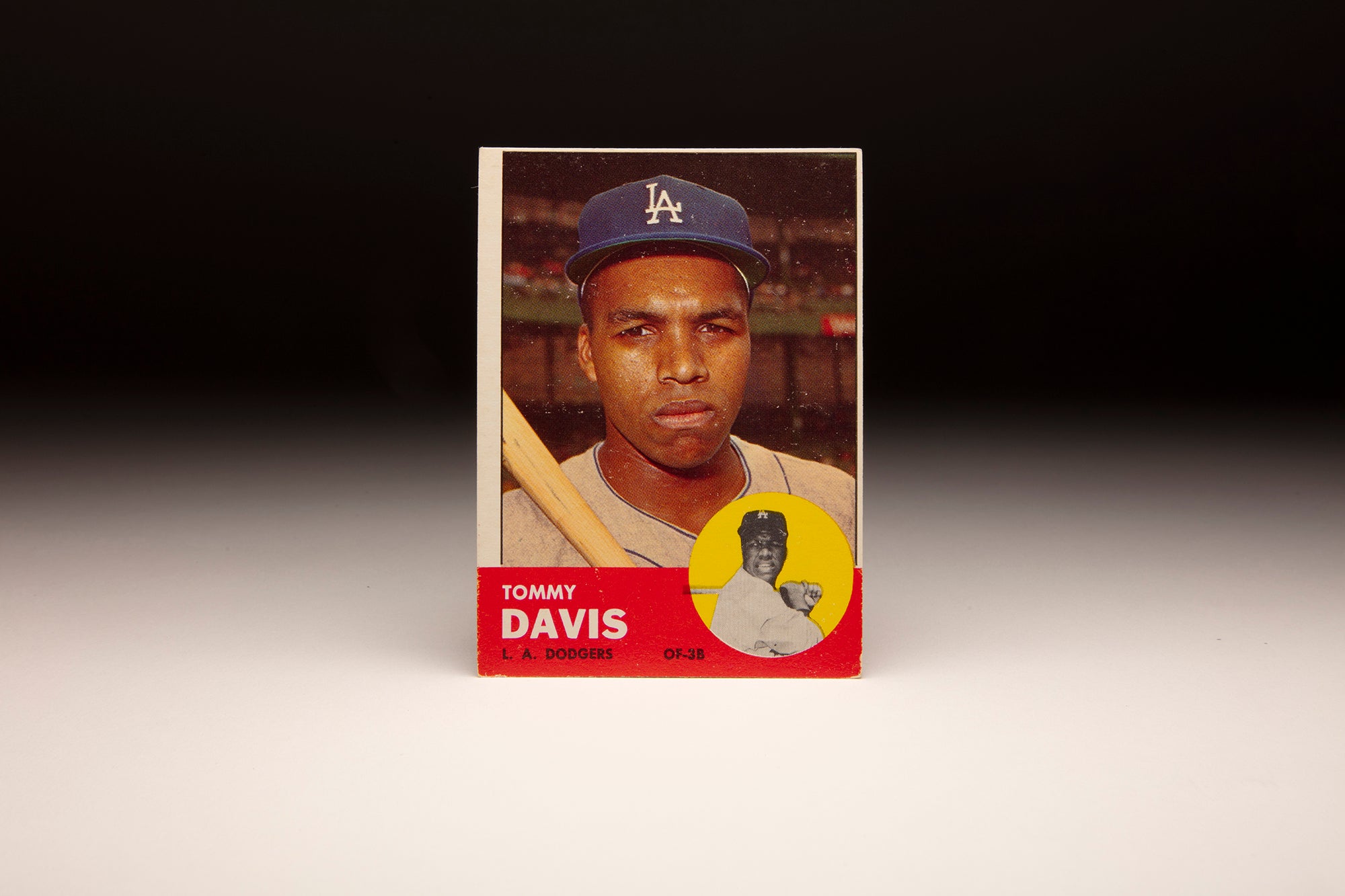

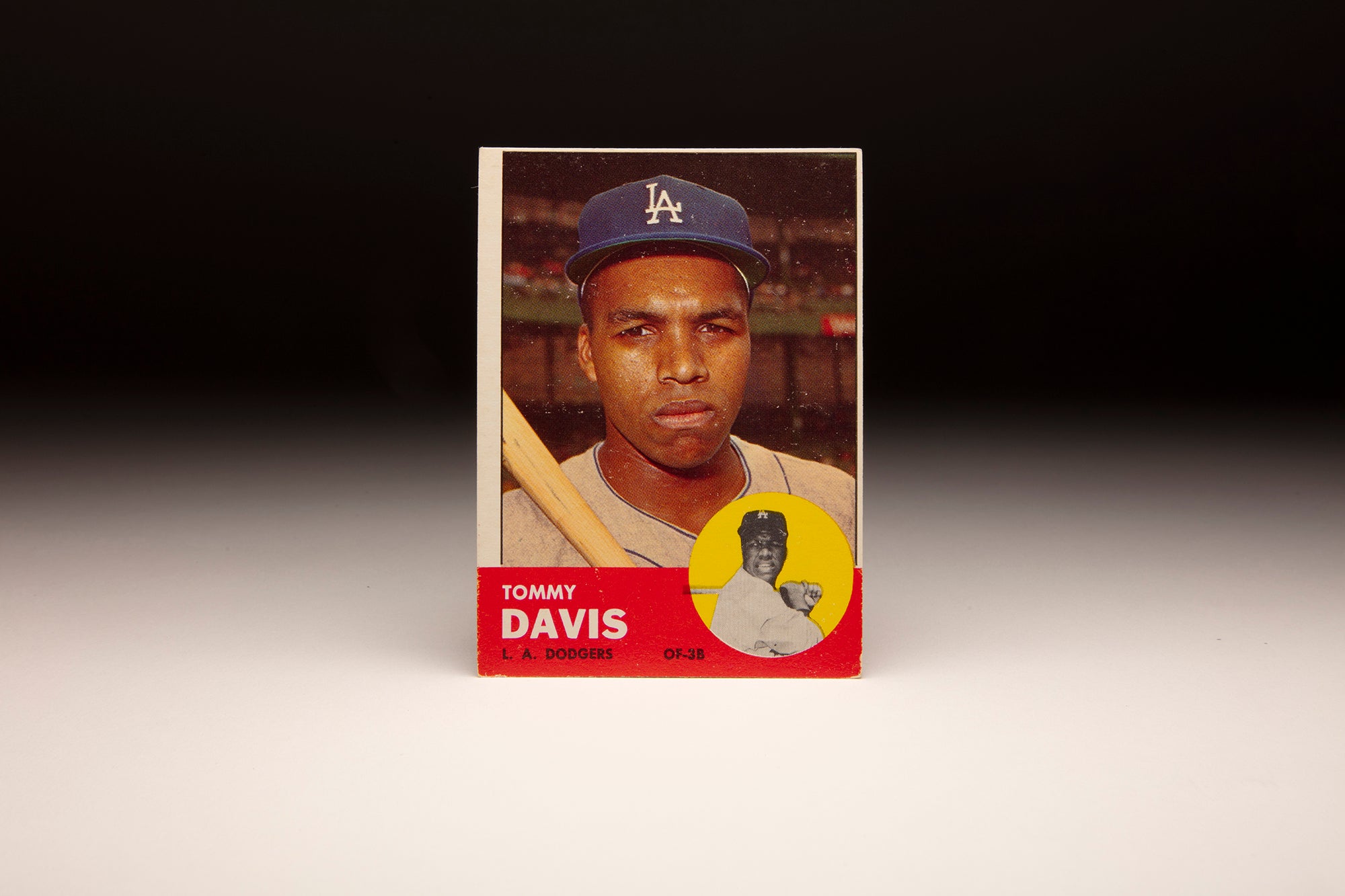

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Tommy Davis

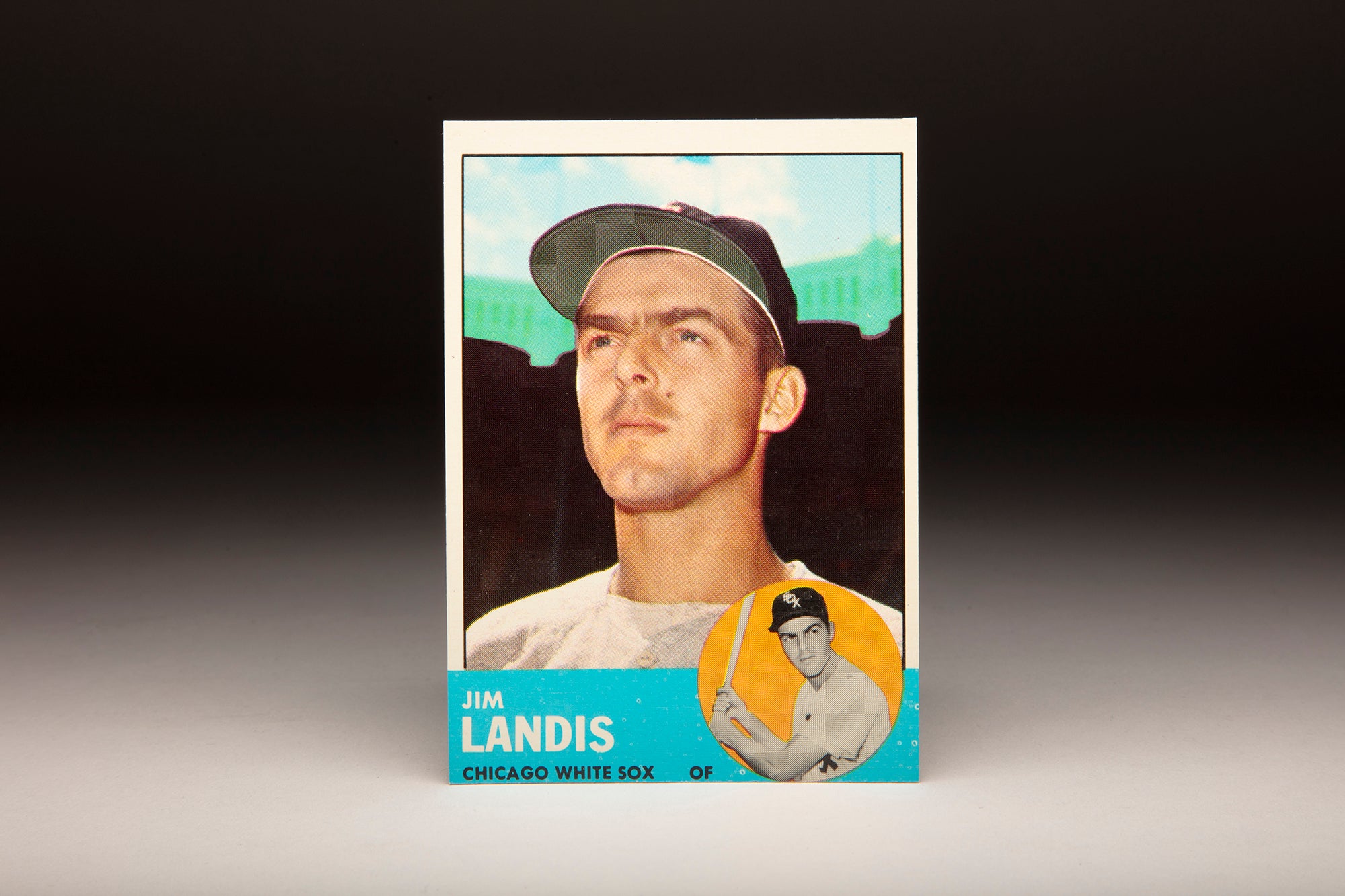

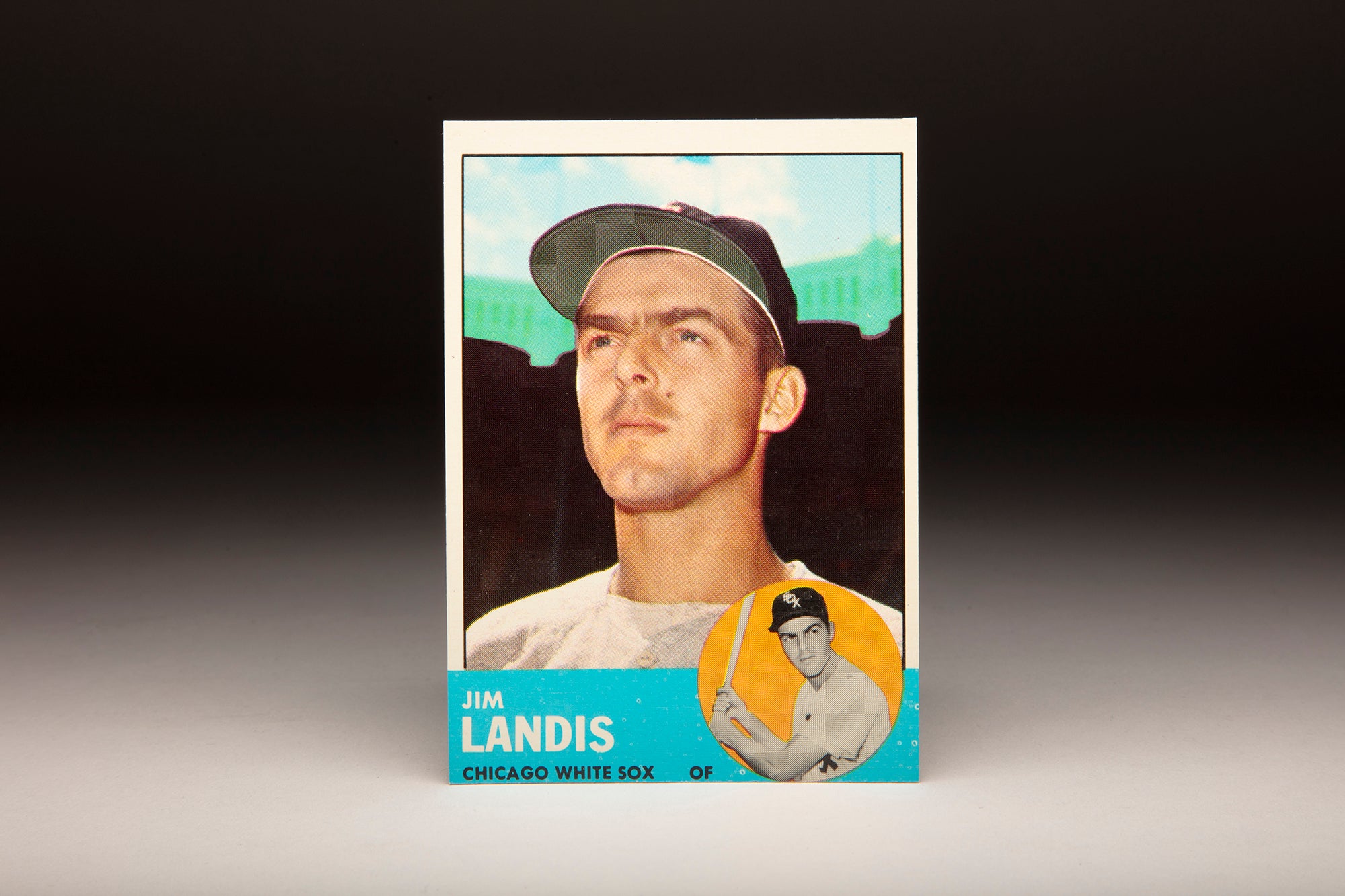

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

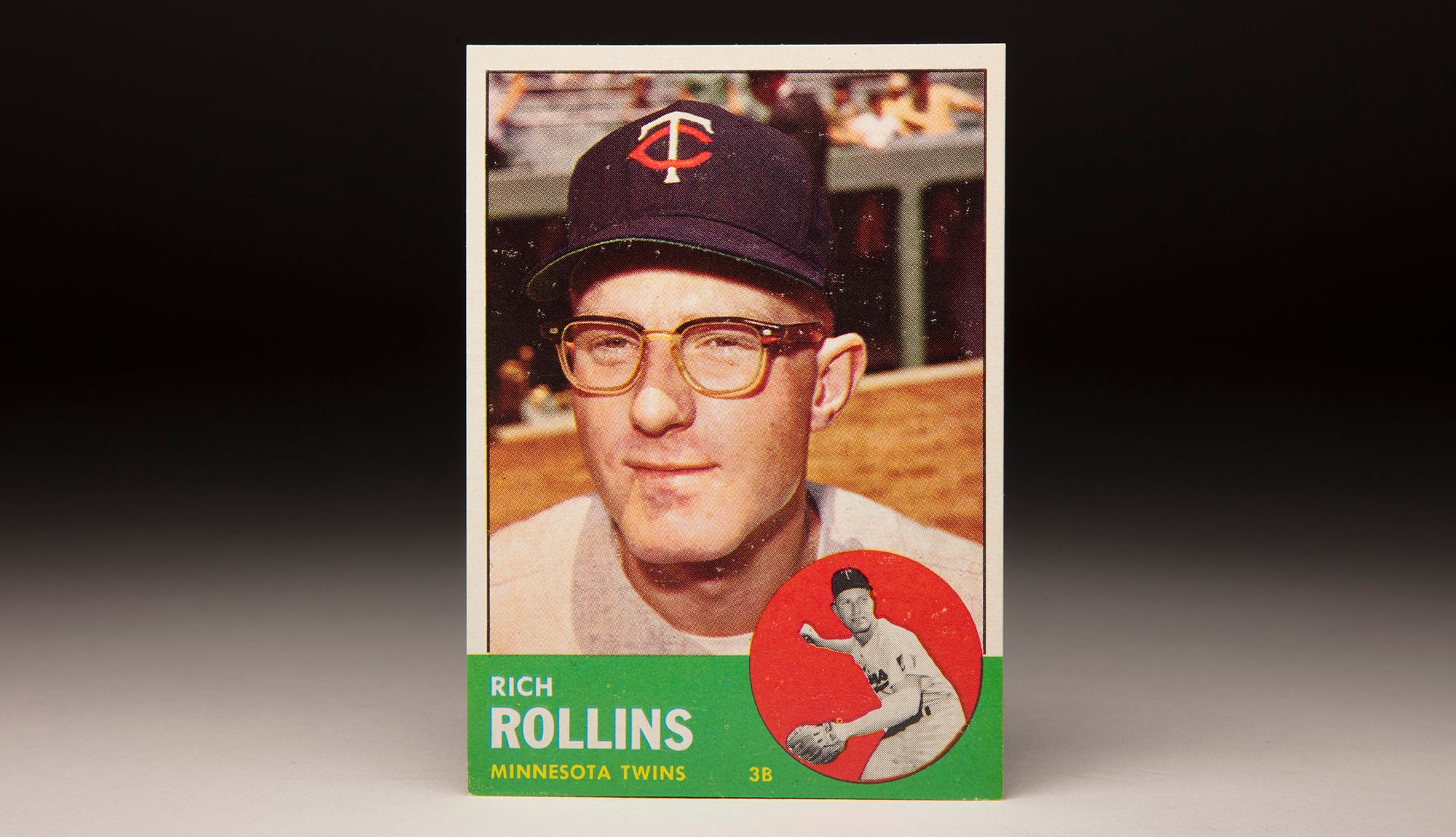

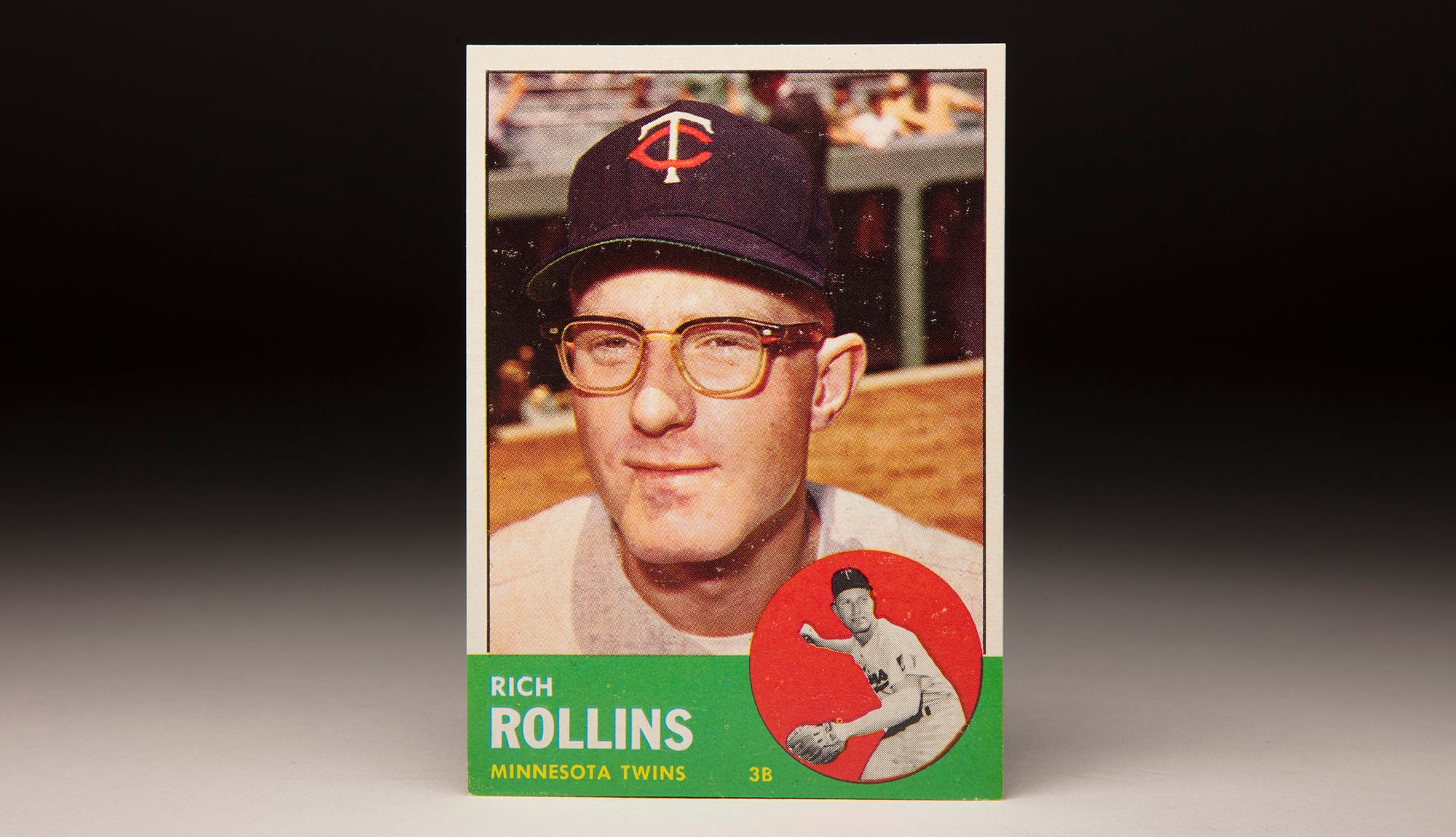

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Rich Rollins

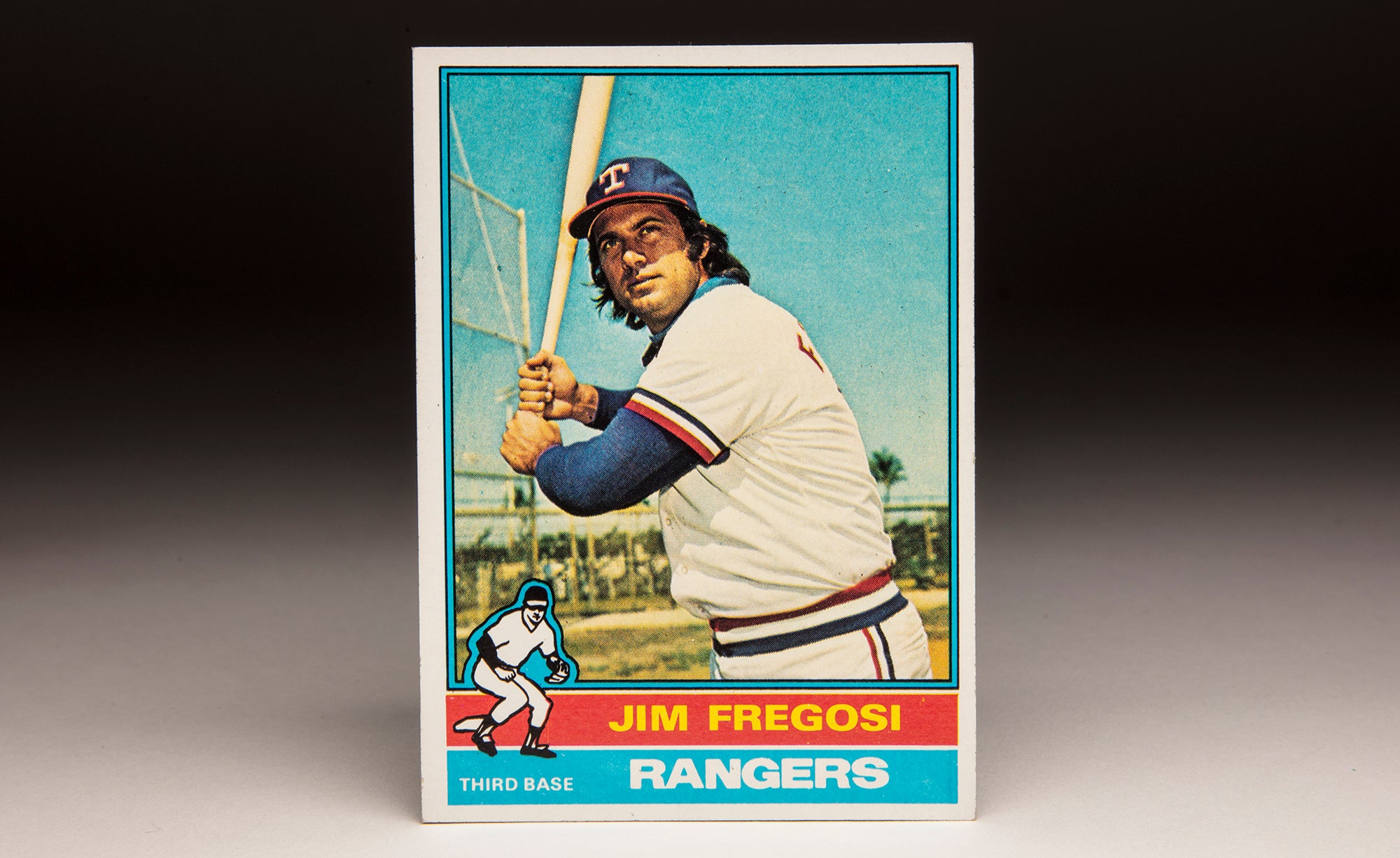

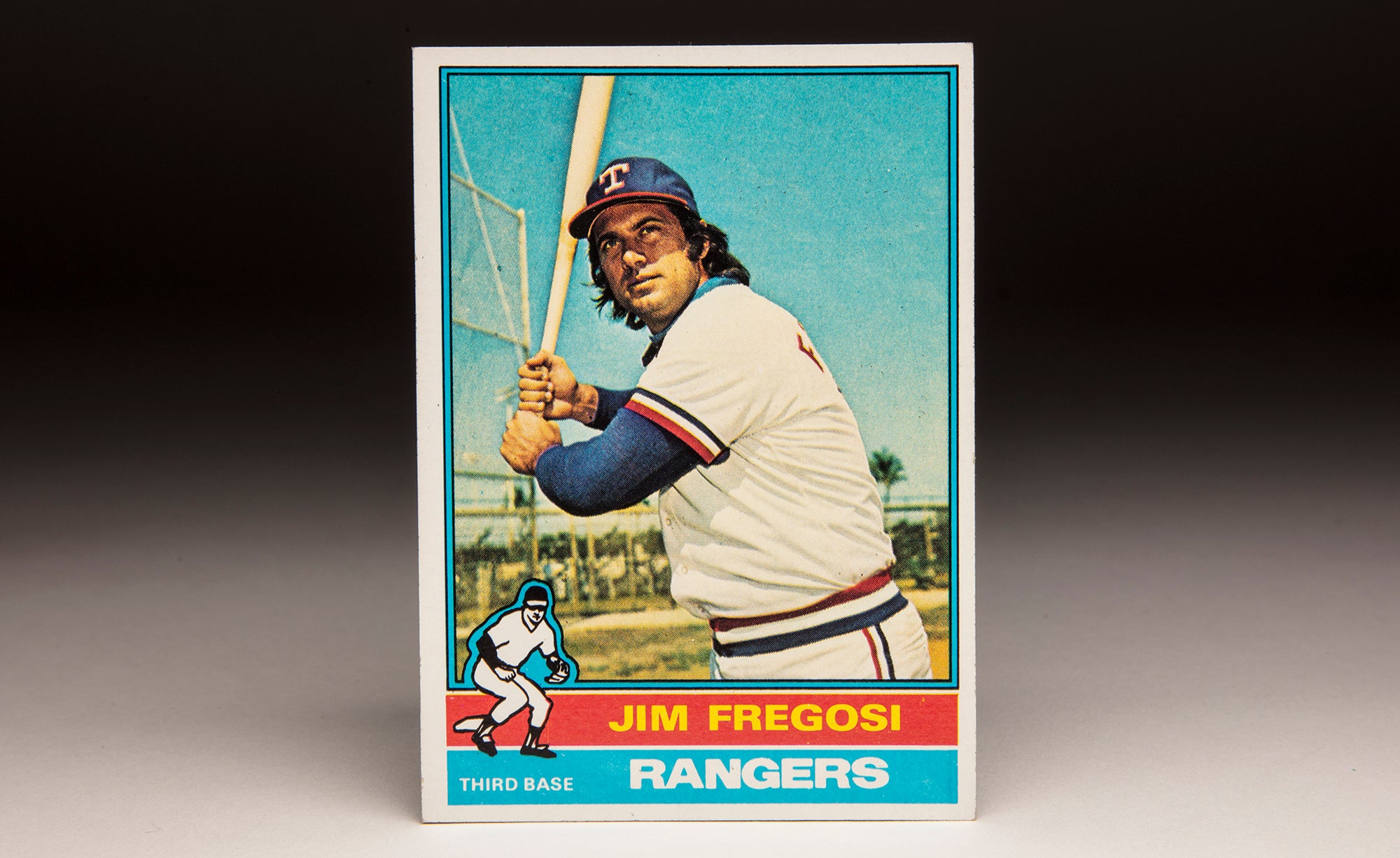

#CardCorner: 1963 and 1976 Topps Jim Fregosi

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Tommy Davis

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Rich Rollins