- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 and 1976 Topps Jim Fregosi

#CardCorner: 1963 and 1976 Topps Jim Fregosi

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With a name like Jim Fregosi, it was understandable that us youngsters growing up in Westchester County, at least those with an affinity for horror films, had some fun with that moniker. Inevitably, we referred to him as “Bela Fregosi” or “Jim Lugosi,” a direct reference to the star of the original Dracula, Bela Lugosi. Or we might say Fregosi’s name with that slow, exaggerated Transylvanian pronunciation, the way that Lugosi spoke his words so memorably in his 1931 starring role as The Count.

In the early 1970s, we played around with those names so much that some unsuspecting non-horror fans might have thought that it was actually Lugosi playing shortstop for the California Angels back then. In reality, Lugosi was already deceased, having passed away in 1956 from a heart attack. As for Fregosi, he had recently been traded to the New York Mets in the blockbuster deal for Nolan Ryan. By coincidence, Fregosi’s career would fall off appreciably after the trade, just as Lugosi’s Hollywood career did in the aftermath of his 1930s prime.

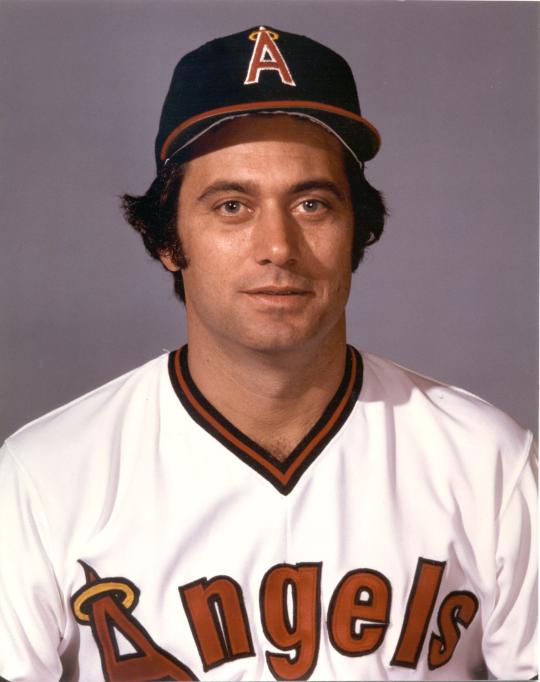

Fregosi was one of those players whose physical appearance changed drastically from the start of his career to the end. Every player ages, with many adding weight and gray hairs as they move into their 30s. But in Fregosi’s case, the physical changes were so dramatic as to be stunning.

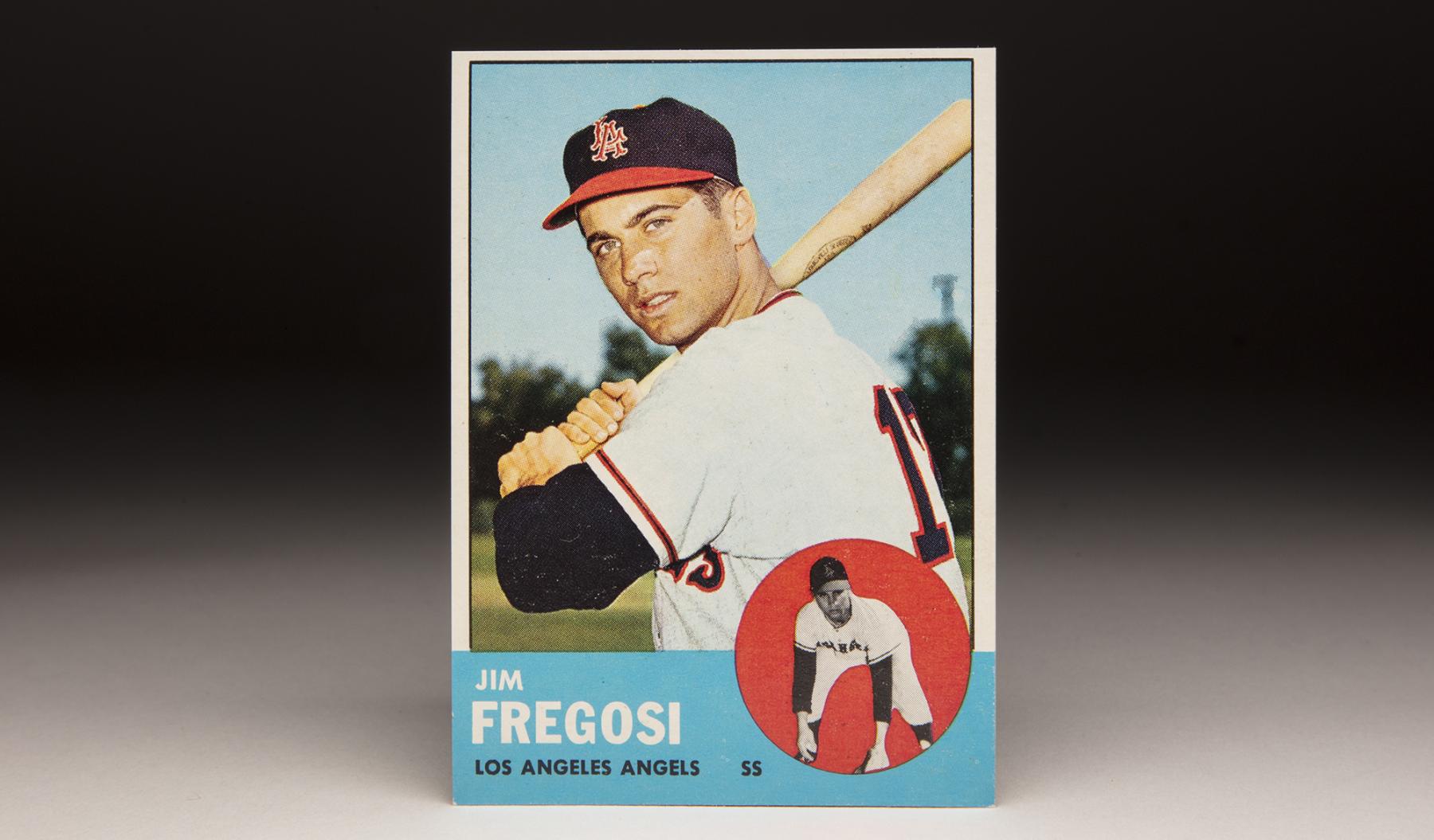

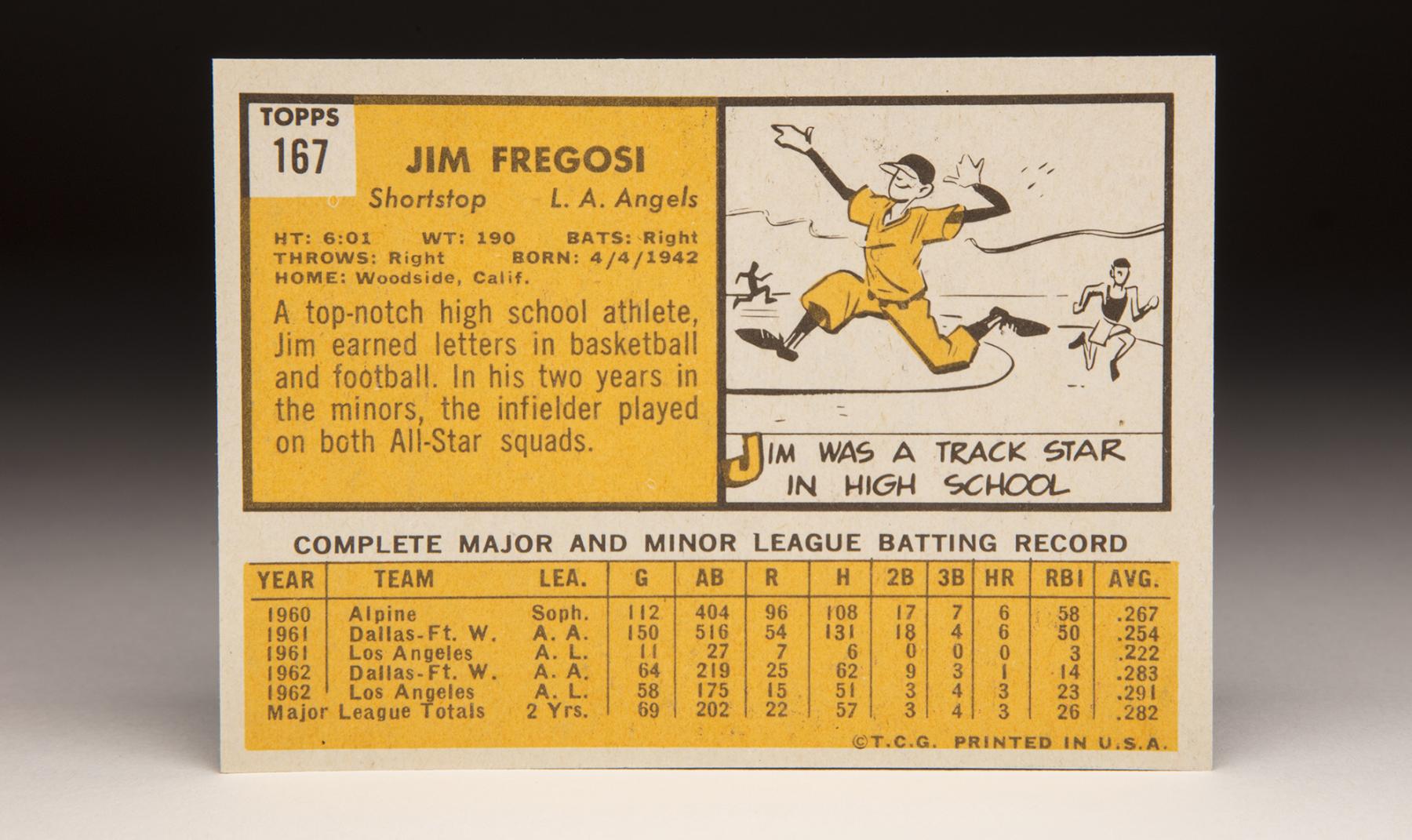

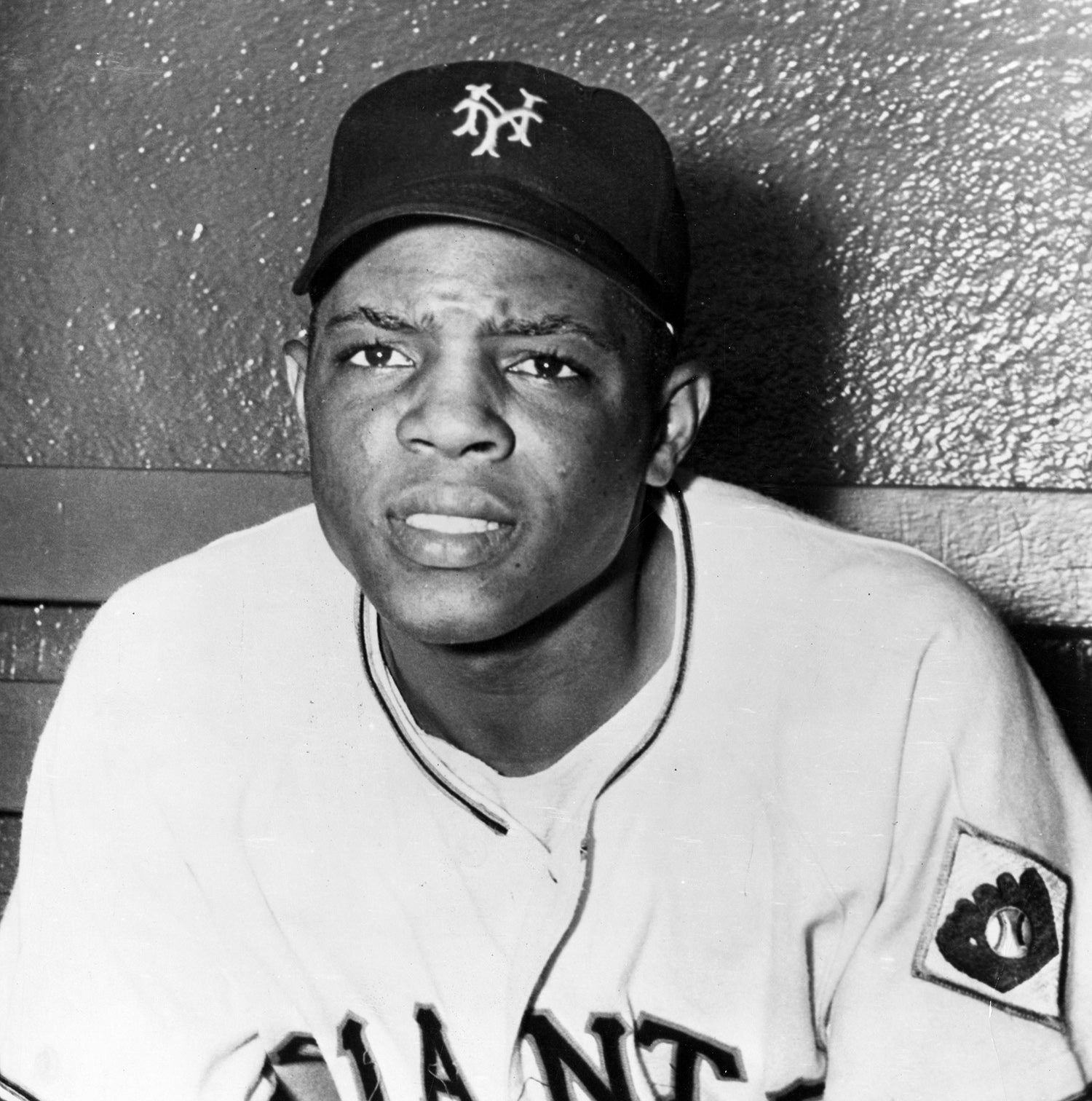

Fregosi’s 1963 Topps card, the second produced by the company, shows him in the prime of youth, with a clean-shaven baby face, a lean body and a close-cropped short haircut in keeping with the styles of players in that era. Frankly, this is Fregosi from a time that I don’t remember quite as well. I wasn’t born yet in ‘63 and wouldn’t start following the game until my seventh birthday – which didn’t come until 1972.

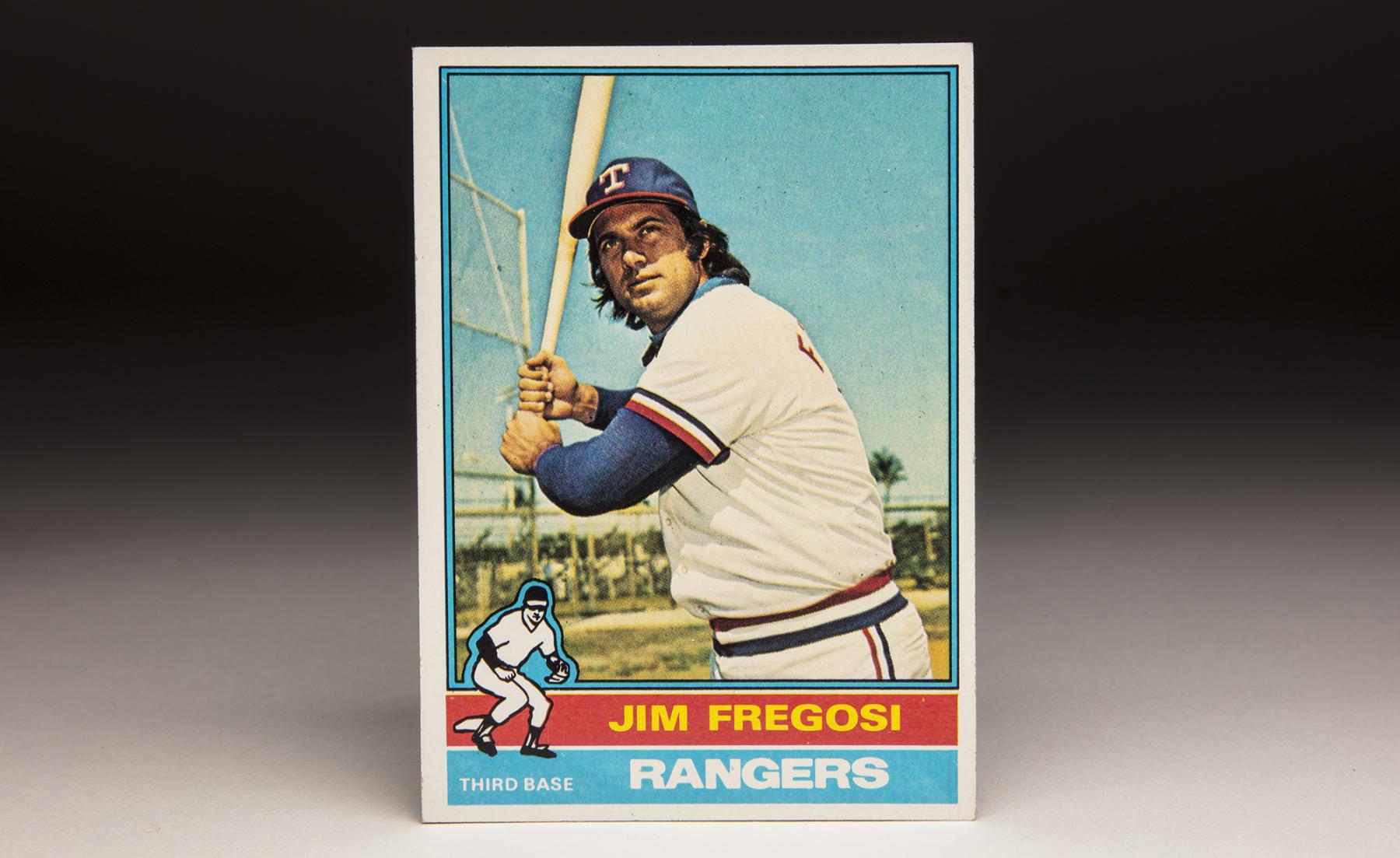

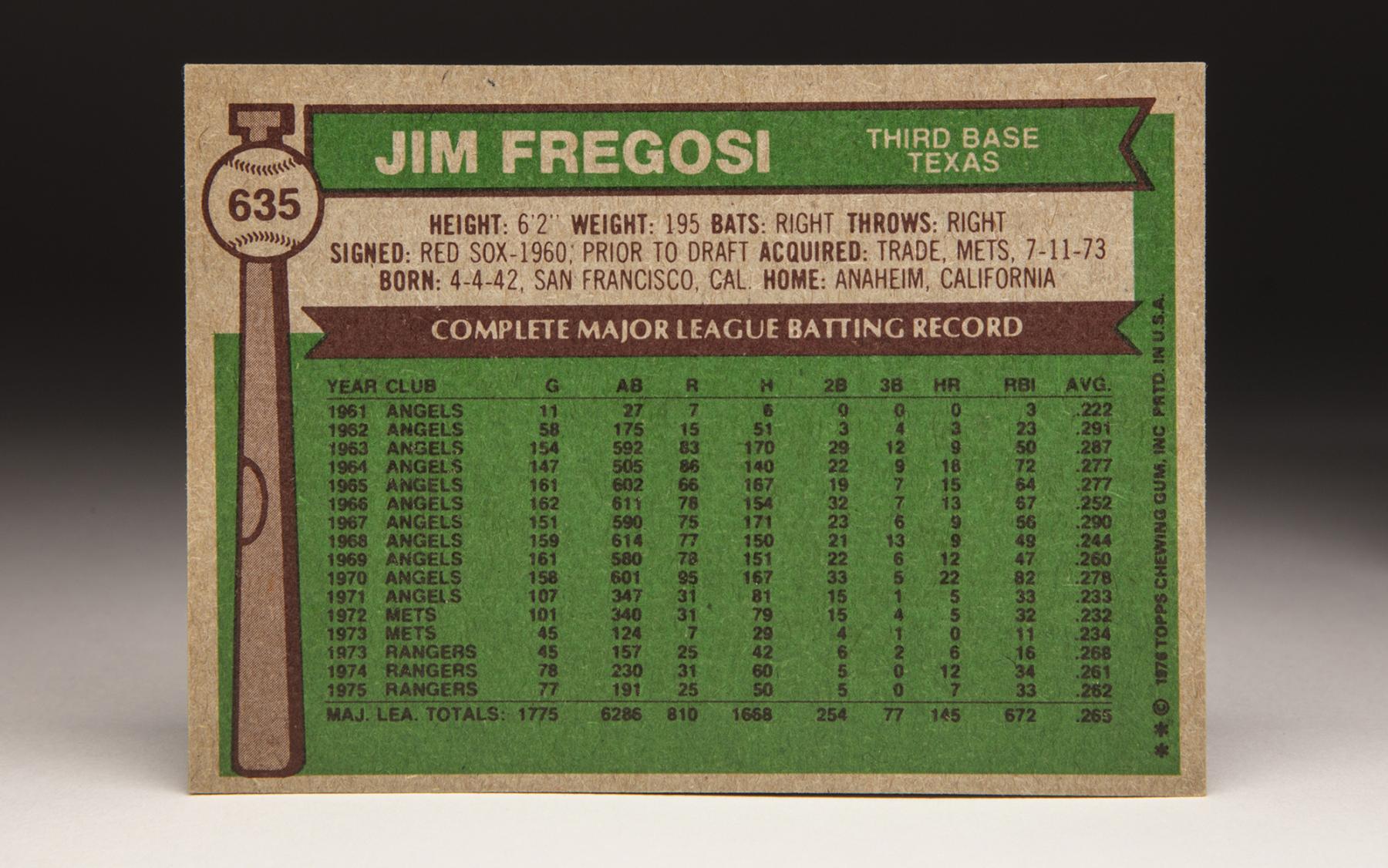

The Fregosi that I remember more closely resembles the one seen on his 1976 Topps card. It is 13 years later than the first Topps card, but it could just as well be 30 years. This Fregosi has long black hair flowing down over his collar, a fuller and more circular face, and an expanding waistline that is only underscored by the beltless polyester pants of the era. In this shot, Fregosi looks nothing like his former self. If you were to put these two cards next to each other, and cover the names and the uniform logos, you would be hard-pressed to conclude that these were photographs of the same ballplayer.

By 1976, Fregosi was near the end of his career. At his peak in the 1960s, Fregosi was about as good a shortstop as could be found. He had no legitimate weakness in his game. He could hit, hit with power, steal an occasional base and play a Gold Glove caliber shortstop. He also hustled and provided leadership in a way uncharacteristic of players still in their 20.

As good a shortstop as Fregosi was, he was a player who somehow got away from his original organization and made his way to an expansion team. In 1960, the Boston Red Sox signed Fregosi to his first contract, giving him a bonus of $20,000. They told him to report to Alpine, Texas, a Red Sox affiliate in the Class D Sophomore League. There he batted a respectable .267, drew 74 walks, and hit six home runs – and played well enough to make the All-Star team.

After the 1960 season, the Red Sox had to decide which players to protect from the upcoming expansion draft. Since the 18-year-old Fregosi wasn’t anywhere near ready for major league duty, the Red Sox left him unprotected. Given his lack of readiness, the Sox figured that neither of the two American League expansion teams, the Los Angeles Angels or the Washington Senators, would draft a player so far from the big leagues. To the surprise of many, the Angels decided to take the patient approach and make Fregosi the 35th pick of the expansion draft. They assigned him to Triple-A Dallas/Ft. Worth, their affiliate in the American Association.

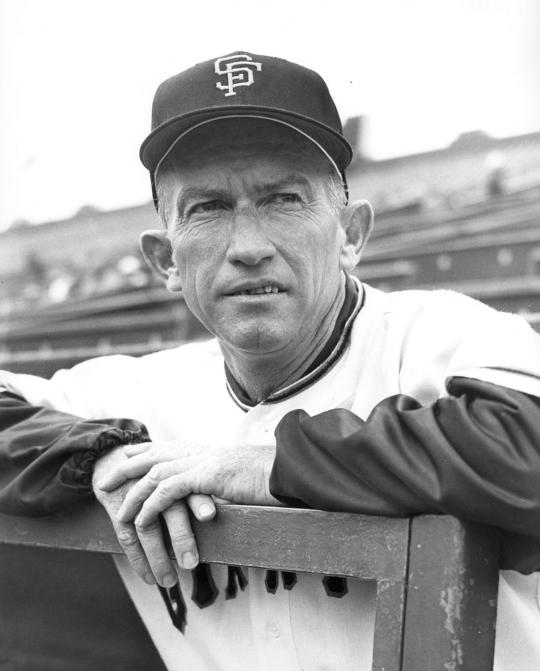

Fregosi made 53 errors at Dallas/Ft. Worth but showed enough with the bat to earn a September call-up to the Angels. He then returned to Triple-A to start the 1962 season, continuing his minor league apprenticeship. By the middle of the summer, the Angels brought him to Los Angeles and made him their starting shortstop. It did not take long for Fregosi to make a sterling impression on his manager. “This boy is going to be the Angels’ shortstop for many years,” Angels manager Bill Rigney informed the Sporting News. “Next to Willie Mays, he has more ability than any young player I’ve ever managed.” Rigney, of course, had managed Mays during his days as manager of the New York/San Francisco Giants.

The pressure of being named in the same breath as Mays had little tangible effect on Fregosi. Over 58 games, he batted .291. Thanks to such a good impression, Fregosi was the club’s Opening Day shortstop in 1963. He played well both offensively and defensively, earning some support in the American League MVP balloting. Then came his breakout season of 1964. Fregosi hit with considerable power, clubbing 18 home runs, while also doubling his walks total, from 36 to 72. Now a far more disciplined hitter with a better understanding of the strike zone, he emerged as the best hitting shortstop in the entire league.

Fregosi would never match his career season of 1964, but remained a power-hitting shortstop and a capable offensive threat in an era dominated by pitching. In 1966, his hitting took a downturn, admittedly because he reported to Spring Training 20 pounds overweight, but he improved his conditioning in 1967. Lighter and quicker, Fregosi earned the first (and only) Gold Glove Award of his career.

After a falloff in power in 1967 and ‘68, Fregosi bounced back with 12 home runs in 1969. He also drew 97 walks, helping elevate his on-base percentage to .381. The following summer, he enjoyed a banner season, hitting a career-best 22 home runs with an OPS of .812. For the fifth consecutive season, Fregosi made the American League All-Star team. And for the eighth consecutive year, he received some support in the MVP balloting.

Not only did Fregosi put up good numbers, but he also brought a set of intangibles to the team. He hustled at all times and established a reputation for playing while hurt. Ever the gamer, the Angels came to regard him as an extension of the coaching staff. “It is one thing to say that Fregosi is a great player, but it goes beyond that,” Angels coach Norm Sherry told local sportswriter Ross Newhan. “He’s a leader, a help to his manager, a guy who will kick the other players in the rear.” The fans in Southern California also came to appreciate Fregosi, who emerged as the most popular player on the Angels during their first decade as a franchise.

The first sign of decline in Fregosi’s game did not occur until 1971, when hit only five home runs while appearing in 107 games. An injury played a major factor. He had to miss a significant stretch of time with a tumor in his foot. The tumor proved to be non-cancerous, but it prevented him from playing at his usual high level. For the Angels, it was another setback in a season of disasters. The 1971 Angels became fractured because of problems affecting Alex Johnson, a feud between Johnson and utility infielder Chico Ruiz, and general dissension under manager Lefty Phillips.

Toward the end of the season, the Angels moved Fregosi to left field, an indication that they felt he was no longer capable of playing shortstop. Not long after, rumors sprung up that Fregosi would be named the team’s player/manager, amidst hopes that he could restore order to the clubhouse.

The rumors turned out to be false. Firing Phillips, the Angels instead hired Del Rice to manage the club. It was one of several moves that the Angels executed, as they looked to distance themselves from the nightmare of 1971. As part of a series of wholesale changes, they released veteran outfielder Tony Gonzalez and traded Johnson to Cleveland for Vada Pinson. They also decided to consider trade offers for Fregosi, who was approaching 30 and putting on weight. The New York Mets, desperate for a third baseman, came calling. They believed that Fregosi could make a smooth transition from shortstop to the hot corner.

The Angels made it clear that they wanted a lot for Fregosi, who remained their most popular player. The Mets agreed to give up four young players: three minor leaguers and a promising right-hander named Nolan Ryan. It would turn out to be one of the most earthshattering trades in baseball history.

With slick-fielding Buddy Harrelson at shortstop, the Mets announced that Fregosi would be their Opening Day third baseman in 1972. Up until that point, the Mets had used 45 players at third base over their 10-year history. General manager Bob Scheffing felt confident that Fregosi would stabilize the position. He harbored little concern about the switch in positions, figuring that if Fregosi could handle the demands of shortstop, he could easily tackle third base.

In theory, the move made some sense. But when Spring Training arrived, Fregosi reported to camp overweight. The lack of conditioning angered manager Gil Hodges, who had expected a leaner and quicker Fregosi.

Every day in camp, Hodges hit dozens of ground balls to Fregosi, helping acclimate him to his new position. One day, Hodges hit a grounder that took a bad hop and caught Fregosi on his bare hand, specifically his thumb. The grounder fractured Fregosi’s thumb, putting him in a cast for the rest of Spring Training.

Determined to come back quickly, Fregosi returned to the playing field in time for Opening Day, which arrived late because of the players’ strike. In reality, Fregosi came back too soon from his broken hand. The thumb still bothered him, particularly at the plate. By his own admission, Fregosi’s eating and drinking habits also contributed to a bad season in New York. “I was leading the good life and I loved it,” Fregosi told Jack Lang, the Mets’ correspondent with the Sporting News. “But I was paying for it on the field.”

For the season, he hit only .232 with five home runs, numbers that were nearly identical to his subpar 1971 performance. The Mets hoped that his second season in Queens would reveal more of the old Fregosi. The veteran infielder stopped drinking and reported to Spring Training in better shape, but his play still suffered. Over his first 45 games in 1973, he batted .234 without a single home run. The Mets decided to give up on the former All-Star. On July 11, after watching him clear waivers, the Mets sold Fregosi to the Texas Rangers, receiving only a small sum of cash in return.

In contrast to the Mets, the Rangers viewed Fregosi as a utility player. Playing for manager Whitey Herzog, Fregosi filled in at third base and first base. The following year, he continued to perform as a bench player for new manager Billy Martin. Fregosi hit 12 home runs in his role as a supersub, making him one of the more productive backup players in the American League. Fregosi remained with the Rangers until June of 1977, when Texas traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder/catcher Ed Kirkpatrick.

Fregosi performed admirably for the hard-hitting Pirates, putting up a .908 OPS as a backup infielder to Bill Robinson and Phil Garner before slumping the following spring. In the middle of the 1978 season, the Pirates received a call from the Angels’ front office. Angels owner Gene Autry wanted to see if Fregosi had any interest in becoming the team’s manager. Fregosi had already accumulated some experience in the dugout, having worked one season of winter ball back in 1970. Would Fregosi be willing to give up his playing career to concentrate on becoming a fulltime manager?

He pondered the decision before making up his mind. Fregosi told the Pirates that he wanted to retire so that he could pursue the opportunity with the Angels. The Pirates gave him their blessing. The decision to become manager brought Fregosi full circle with Nolan Ryan, who by now was the established ace of the Angels.

Fregosi took well to his new line of work, surprising no one who had remembered his leadership skills during his playing days with the Angels. In one of Fregosi’s best moves, he made hard-hitting Brian Downing his starting catcher, a change that greatly improved the Angels’ offense. Taking over an underachieving team, Fregosi applied an old school approach and steered the Angels to a strong second-half finish. The next summer, Fregosi’s Angels won the American League West, advancing to the postseason for the first time in franchise history.

Fregosi would have to wait awhile for his next trip to postseason play. After an unsuccessful term leading the Chicago White Sox, Fregosi found satisfaction in 1993 when he guided a wild group of Philadelphia Phillies to the National League pennant. No longer as unyielding in his managerial style, Fregosi became more patient with his players. The approach fit in well with the Phillies, who featured strong, hard-charging characters like Darren Daulton, Lenny Dykstra, Pete Incaviglia, Curt Schilling and Mitch Williams. Despite the team having a number of flaws, Fregosi led the Phillies to within two games of the world championship.

A few years later, Fregosi joined the Toronto Blue Jays under difficult circumstances. During Spring Training in 1999, Jays manager Tim Johnson admitted having lied about seeing combat in the Vietnam War. The Jays fired Johnson; with little advance notice, they made Fregosi their manager. Despite having almost no chance to prepare for the job and the season, Fregosi led the Jays to a record above .500. He did the same next year. But the Jays dismissed him after the second season.

Though he never won a world championship, Fregosi managed for 15 seasons and won roughly 48 percent of his games. Still, Fregosi wasn’t done. He moved on to a scouting position with the Atlanta Braves, where he carved out such a good reputation that he earned the George Genovese Award for “excellence in scouting” in 2010.

During his days in Philadelphia, I happened to visit the Phillies’ Spring Training camp as part of my duties for the Hall of Fame. I saw Fregosi sitting in the dugout and considered approaching him for an interview. His burly appearance, along with his booming voice, intimidated me somewhat. I decided not to pursue the interview. It was a decision I came to regret, upon learning that Fregosi was one of the most open and accessible people within the game. Clearly, this was my loss.

Sadly, all of the baseball world lost Fregosi in February of 2014. Six days after suffering a series of strokes aboard a major league alumni cruise, Fregosi died. He was 71. Fregosi spent 53 of those years in baseball. Whenever I hear his name, a smile comes to me because of the odd connection to Bela Lugosi. That was my early introduction to Fregosi, but I found out that there was a whole lot more to his story than a cool name that rhymed with a Hollywood legend.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

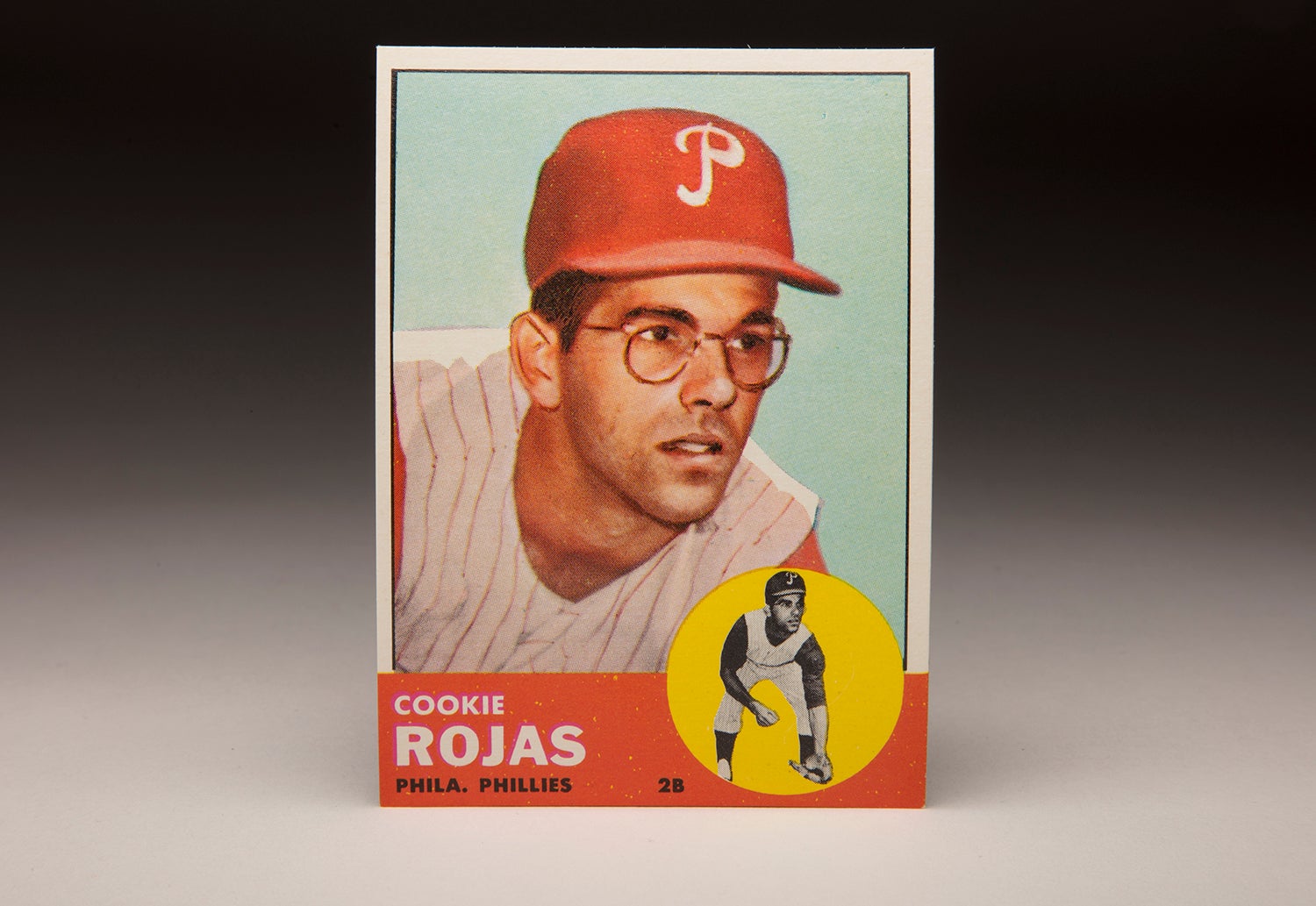

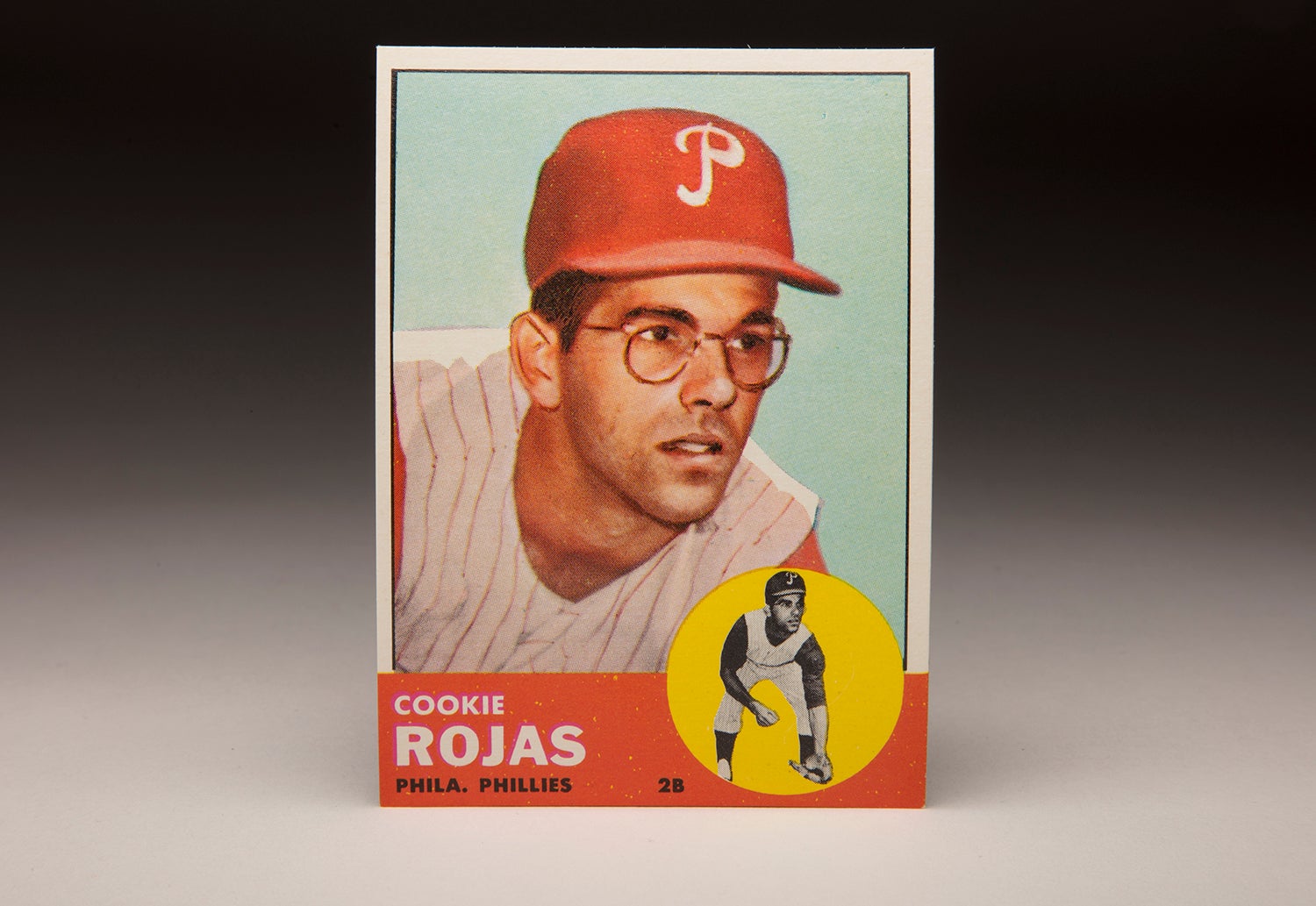

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

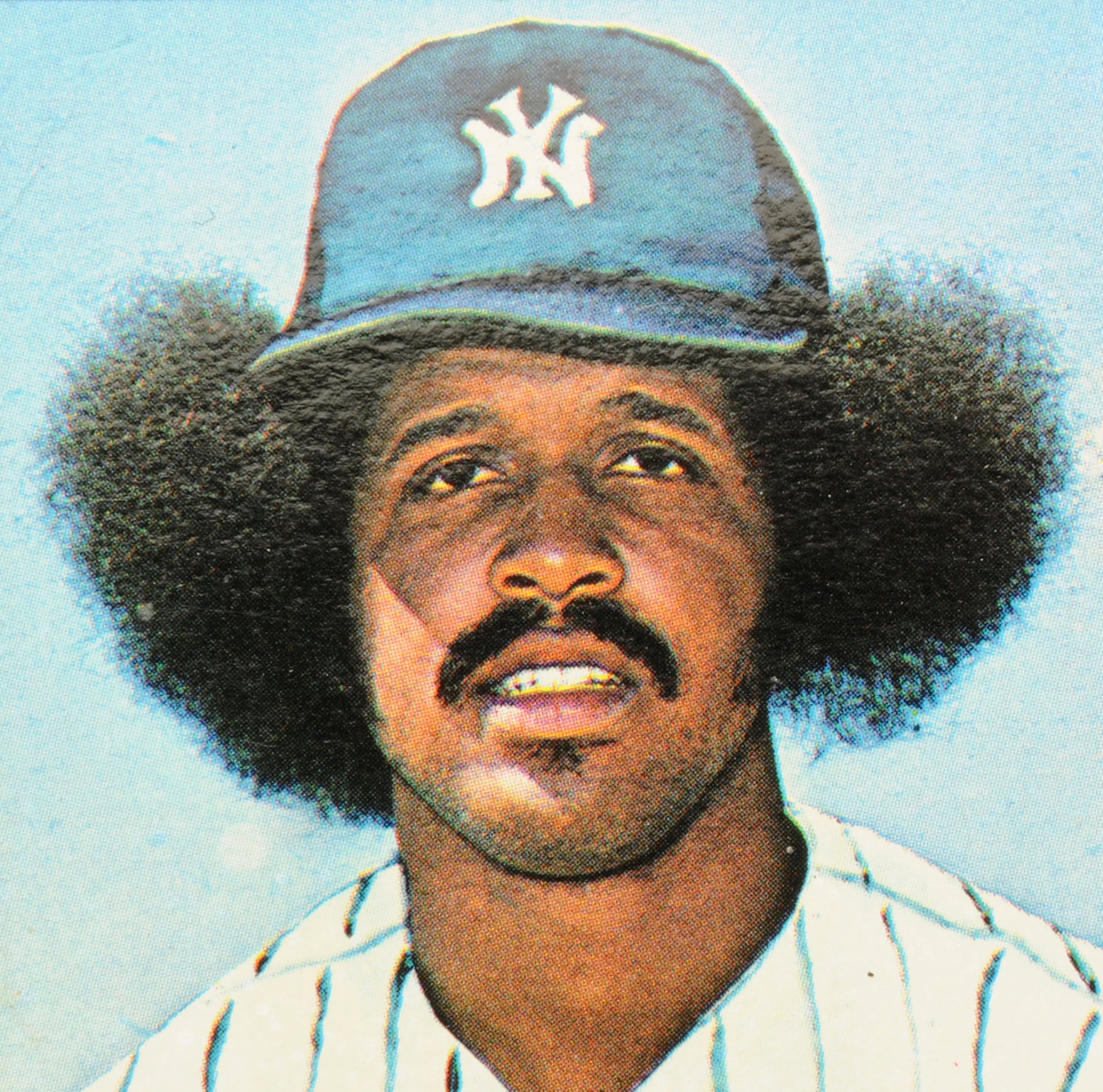

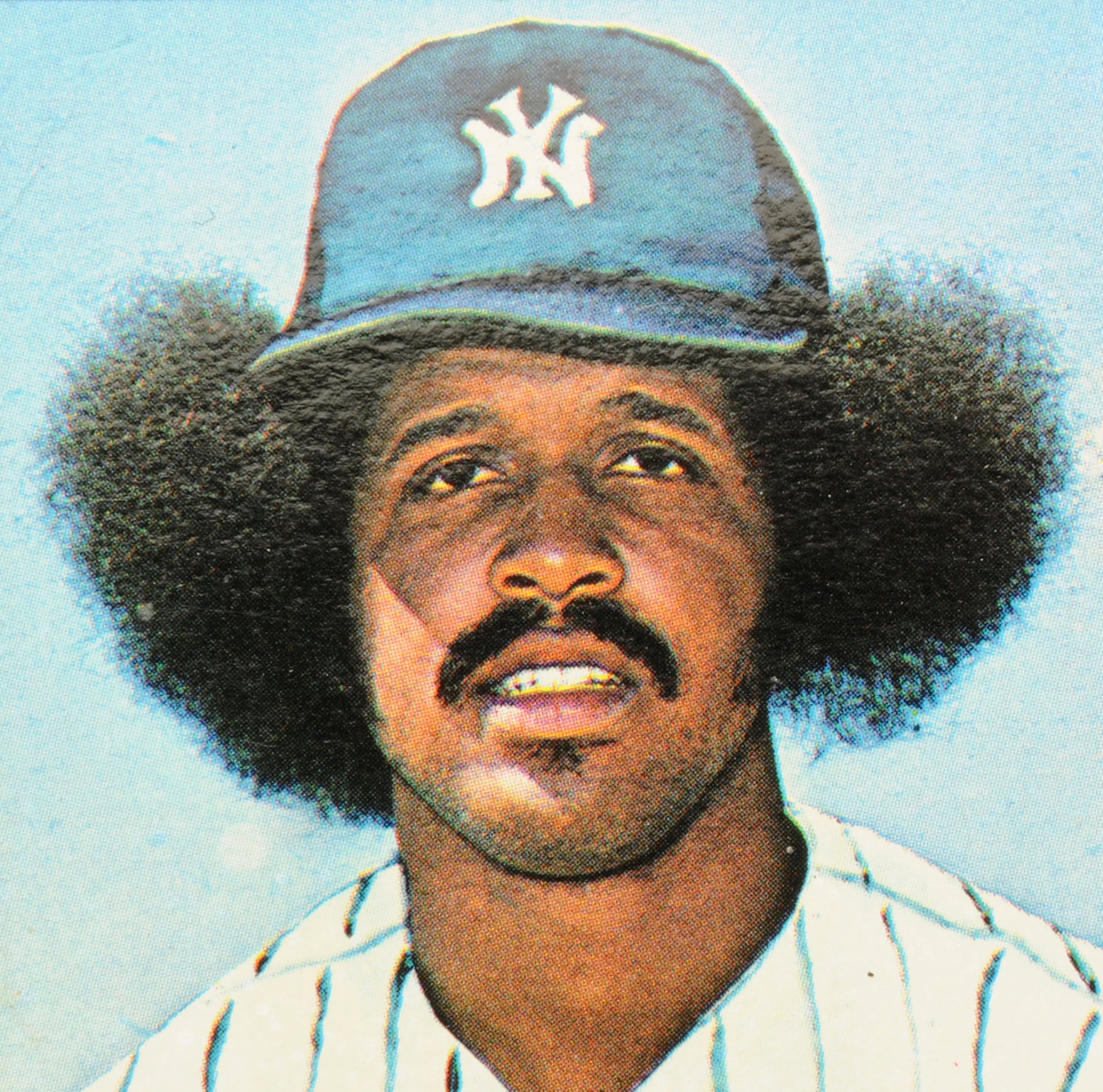

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

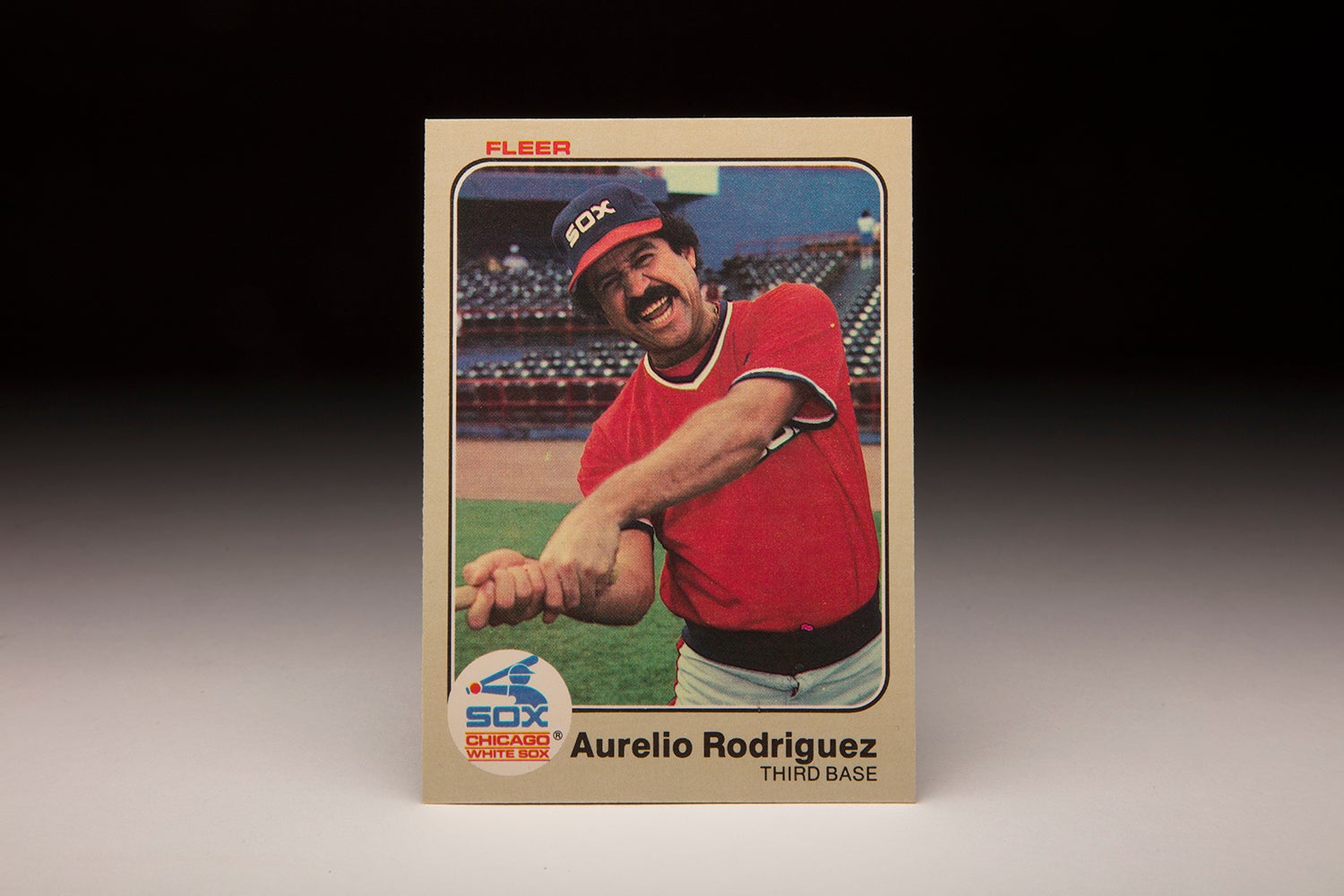

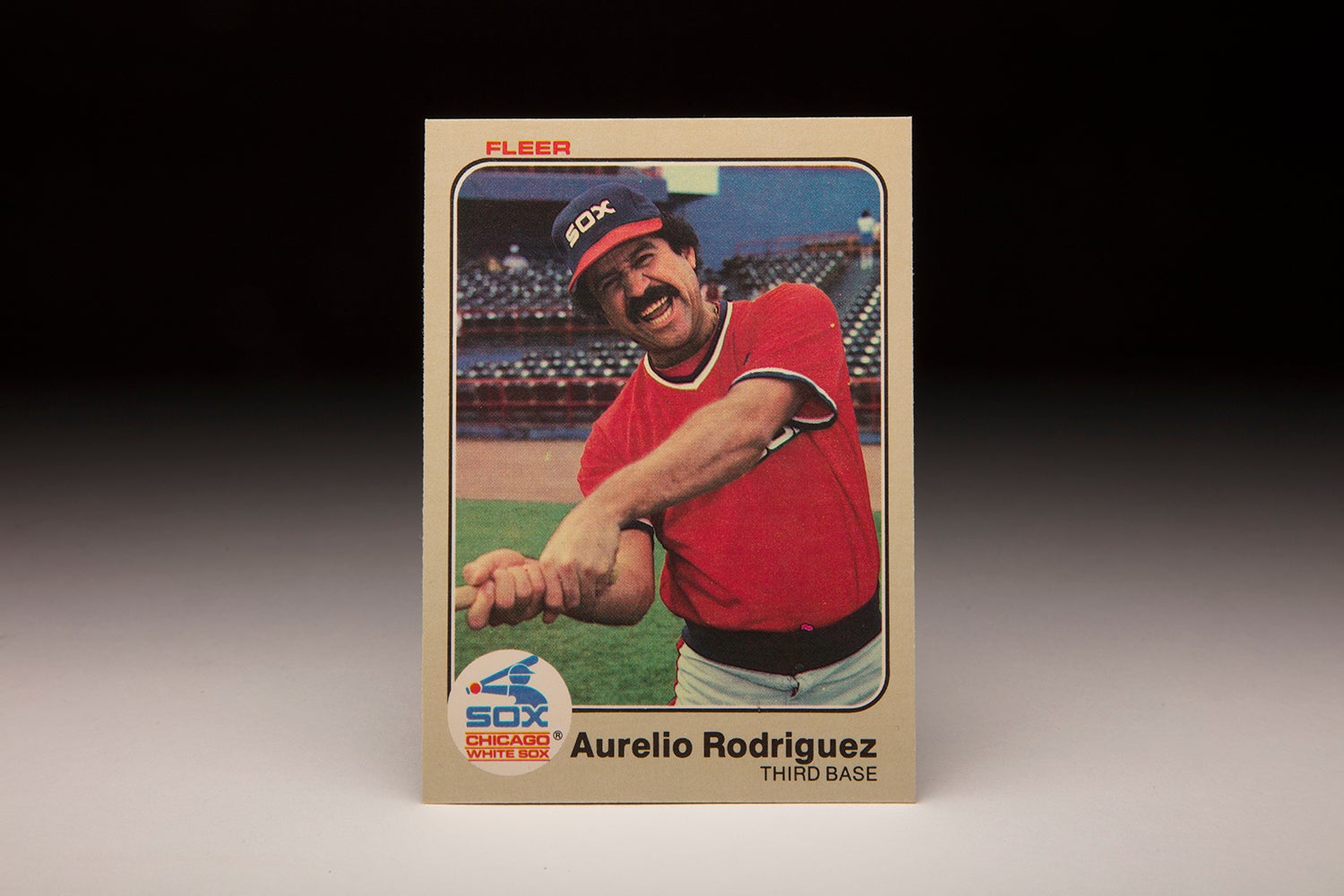

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps & 1983 Fleer Aurelio Rodríguez

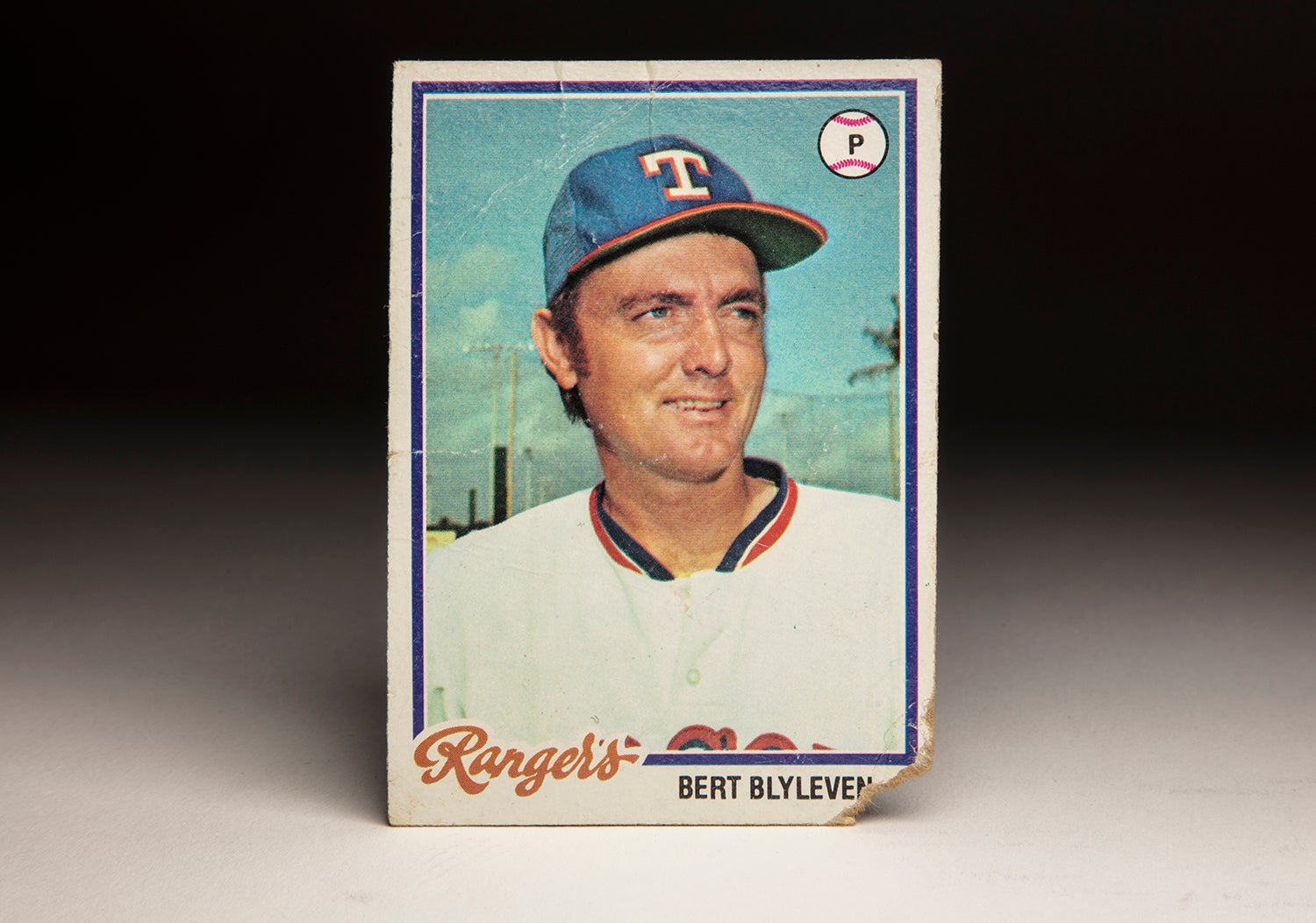

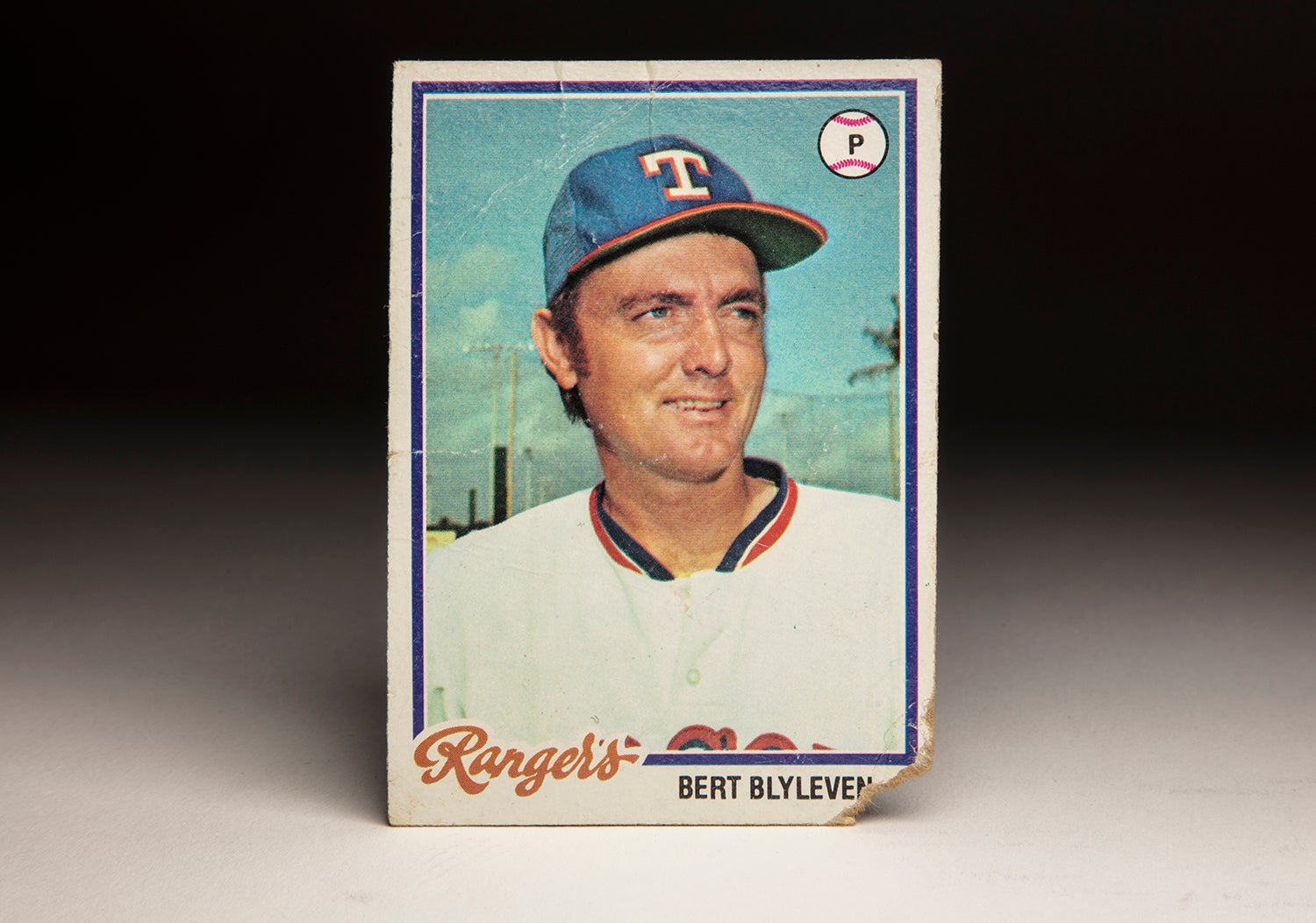

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Bert Blyleven

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps & 1983 Fleer Aurelio Rodríguez