- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

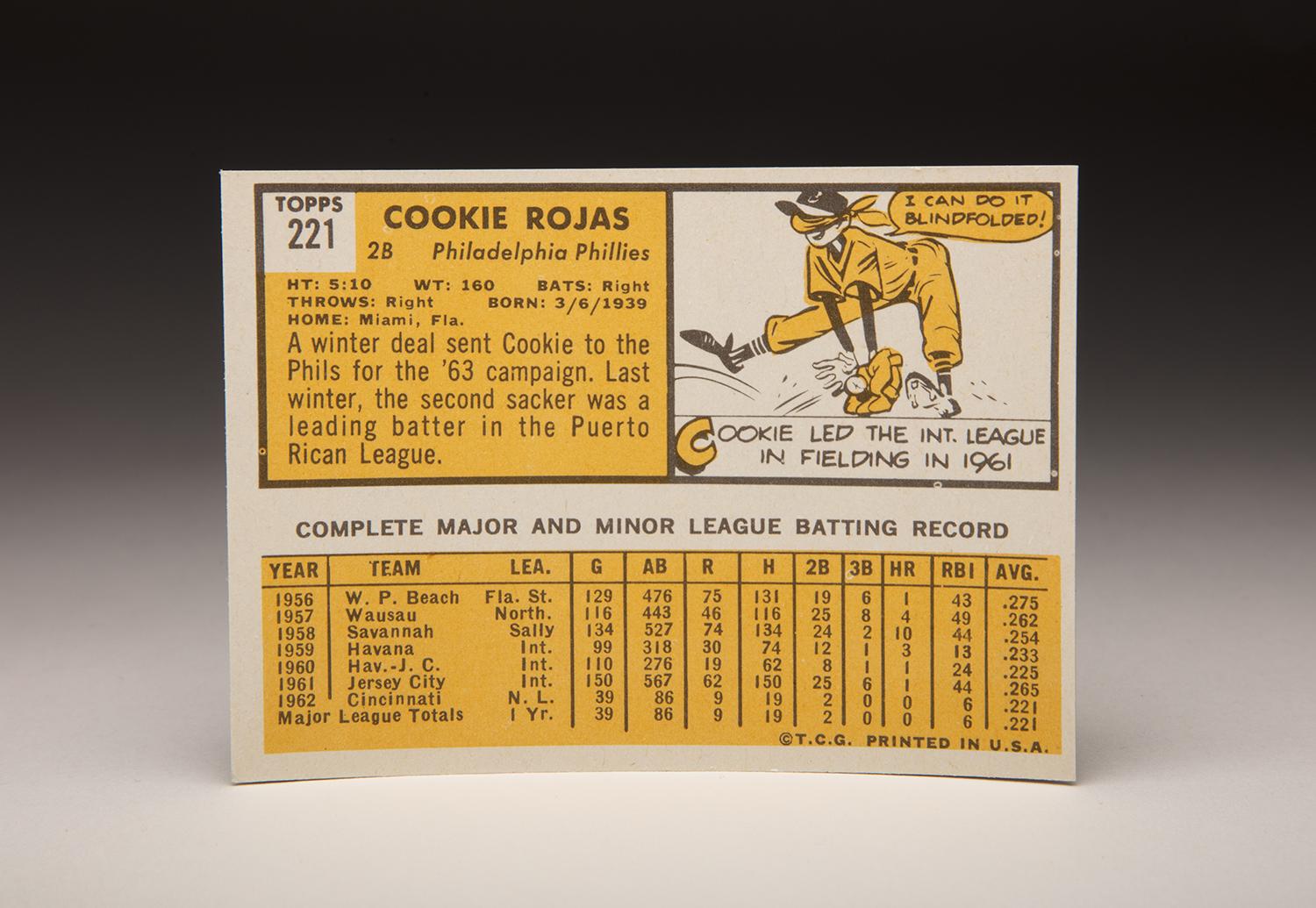

2018 marks the 55th anniversary of one of Topps most intriguing and vibrant sets. The 1963 Topps set gives us two photographic images on the front of the card, one in color and one in black-and-white. The base photograph occupies the majority of a card, while the smaller black-and-white photo can be seen in the lower right-hand corner.

Even with a black-and-white image, there is plenty of color to be found in 1963 Topps. Each card features a wide colored band near the bottom of the card. Topps also incorporates a colored circle in the lower corner, serving as a kind of frame around the smaller photograph. Combined with the vividness of the color photography that Topps produced throughout this set, these design features make the 1963 cards come across as quite striking. Cookie Rojas’ rookie card provides an excellent example of that.

The Rojas card, with its orange band at the bottom, topped off by Rojas’ reddish-orange cap, jumps out among the 1963 selections. It is also an example of early airbrushing for Topps. At the time this photograph was taken, sometime in 1962, Rojas was still a member of the Cincinnati Reds. Over the winter, the Reds traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies. Due to the similarity in the pinstriped uniforms used by the Reds and Phillies in the early 1960s, Topps did not need to do much in terms of altering Rojas’ jersey. But the cap is clearly airbrushed, with the Phillies shade of red and the large ‘P” superimposed over the Reds’ colors and logo. The cap also looks a bit unnaturally large for Rojas’ head, leading us to wonder whether the Topps art department created the cap from scratch. My guess is that Topps did not; I think Rojas simply wore a cap that was one size too large.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

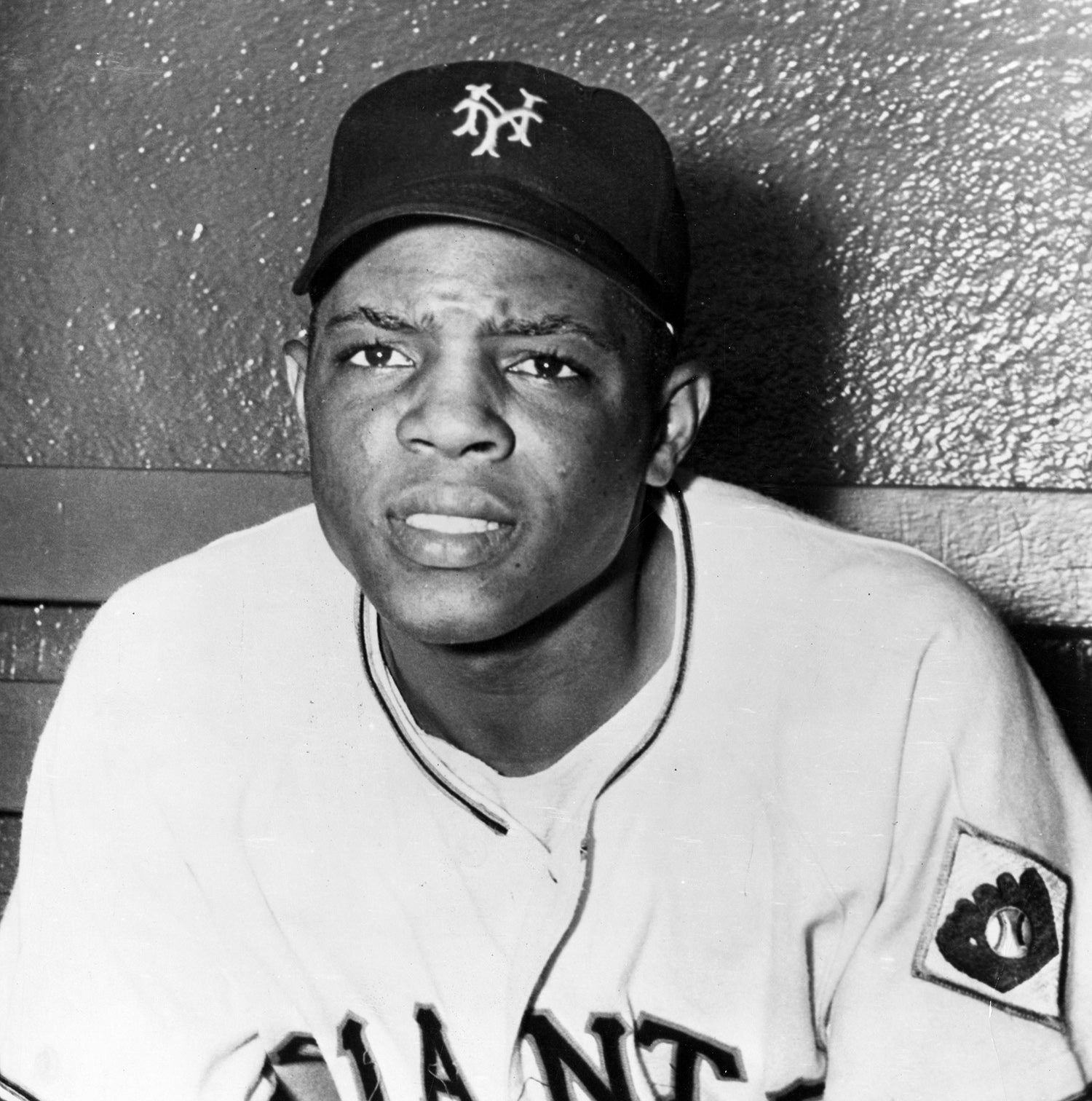

Given the size of the cap and his large, clunky glasses, Octavio “Cookie” Rojas does not look like your classic ballplayer cut from the mold of a Mickey Mantle or a Willie Mays. The glasses do give Rojas the look of a studious, intelligent young man on his 1963 card, but that’s not just a stereotype in this case. As a young student growing up in Cuba, Rojas showed such intelligence that his father, a successful doctor, believed that his son had the ability to become a doctor, too. Rojas, however, showed little interest in medicine; he wanted to play baseball, a less stressful, though still highly demanding occupation.

Contrary to his father’s wishes, the 17-year-old Rojas signed a professional contract with the Reds, who had developed a pipeline of Cuban prospects they assigned through their minor league affiliate, the Havana Sugar Kings. Initially, the Reds promptly assigned Rojas to West Palm Beach of the Florida State League. While playing for the Class D minor league affiliate, Rojas picked up the nickname of “Cookie.” In actuality, Rojas’ nickname since childhood had been “Cuqui,” a Spanish word that means “cute” or “adorable.” But sportswriters confused Cuqui with “Cookie,” and started calling him by that name. Rojas had no special affinity for cookies; the Americanized nickname was simply a mistake, plain and simple.

Almost immediately, Rojas impressed the Reds’ brass with his fielding, which bordered on the brilliant. The Reds had little doubt that Rojas could play second base in the major leagues. But they had severe doubts about his ability to hit. Rojas struggled to hit for average or power, even in the lower minor leagues. In six full minor league seasons, Rojas never batted higher than .275.

In 1959, Rojas moved up to play for the Triple-A Sugar Kings, the Reds’ affiliate in the International League, but batted only .233. He remained at Havana to start the 1960 season, but the Cuban Revolution forced the franchise to relocate in midseason. The Reds moved the franchise to Jersey City in midsummer, pulling Rojas with the rest of the team. Rojas would never return to Cuba, as he became disenchanted with the kind of government imposed by Fidel Castro.

After another full season at Jersey City in 1961, Rojas finally became a Red in 1962. Although he had played a half dozen years in the minor leagues, he was still only 23, still young enough to put together a sound career. Rojas played a utility role for the Reds, but didn’t hit much, resulting in a return to Triple-A Ball, this time at Dallas/Ft. Worth. He came back to Cincinnati at the tail-end of the season, but his lingering offensive struggles convinced the Reds that he would never hit well enough to maintain a major league job. After the season, they gave up on the young middle infielder, sending him to the Phillies for journeyman right-hander Jim Owens, who had struggled mightily in 1962.

The trade would turn out to be a stroke of genius for the Phillies, who were on the cusp of putting together a team capable of contending in the National League. Joining the Phillies for Spring Training in 1963, Rojas played sparingly as a backup infielder to second baseman Tony Taylor and shortstop Bobby Wine. But his role grew in 1964; he became a play-everywhere utilityman who appeared at every positon except for first base and pitcher. He also batted .291, far better than he had done in any minor league season. Rojas’ surprising success with the bat helped the Phillies become a strong contender in the pennant race, only to see the team collapse during the final two weeks of the season.

Rojas’ work ethic thoroughly impressed the Phillies’ brass, especially manager Gene Mauch. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times many years later, Mauch said that he never managed a player who practiced as hard or as well as Rojas. “Cookie played like he practiced,” Mauch told Times writer Ross Newhan. “He was always very well prepared. He had average speed, marginal power, and marvelous hands. He worked at becoming adept at situation baseball. [For example], if the ball had to be bunted, if it had to be directed with the bat, he could do it against any and all people… Cookie practiced better than any player I ever had.”

In 1965, Rojas graduated to a starting role, albeit at two different positions. Sometimes he played second base, and sometimes he played center field. The Phillies knew that Rojas could handle the responsibilities of both positions, but they were shocked at how well he hit. Rojas batted a career-best .303 and reached base nearly 36 percent of the time. Rojas played so well that he earned a few votes in the National League MVP race.

Rojas credited his surge in hitting to a game that was once played at ballparks, but is now mostly a thing of the past: Pepper. It’s a game in which one player tosses a teammate a ball from a short distance, forcing him to react quickly and simply try to make contact with the ball. “I found I couldn’t concentrate in the batting cage because so many people are yelling,” Rojas told the Philadelphia Bulletin. “So I worked on my stroke playing pepper, mostly with Bobby Wine throwing the ball from 60 feet out.”

Wine and Rojas also became a tandem on the infield. When Rojas played second base, he helped form a terrific double play combination with Wine, himself a slick fielding shortstop. Covering tons of ground and turning double plays beautifully, Rojas and Wine inspired some members of the Philadelphia media to come up with the catch phrase, “The Plays of Wine and Rojas.” The catch phrase, a collaborative nickname of sorts, was a takeoff of the popular 1962 film, The Days of Wine and Roses.

From 1966 to ’69, Rojas settled in as the Phillies’ starting second baseman, but retained his versatility. In 1967, he played at least one game at each position, except for first base. He also displayed remarkable bunting skills, which reached a peak when he led the league with 16 sacrifice hits in ’67. But his batting average fell each season in the late 1960s, all the way down to .228 in 1969. Given his decline offensively and the emergence of young second baseman Denny Doyle, Rojas became trade bait. That December, the Phillies included Rojas in a blockbuster deal, sending him and star first baseman Dick Allen, among others, to the St. Louis Cardinals for Curt Flood, Tim McCarver, Byron Browne, and Joe Hoerner.

The trade would become famous as the impetus for Flood’s lawsuit against Major League Baseball, but it would also result in a major jolt to Rojas’ career. “I was 31 years old and didn’t fit into their (the Phillies’) plans,” Rojas told the Nevada Daily Mail. “When I got to St. Louis they had Julian Javier (at second base) and didn’t really need me.” With Javier ahead of him on the depth chart, Rojas became an odd fit in St. Louis. Not surprisingly, his tenure with the Cardinals lasted only 23 games. On June 13, two days before the old trading deadline, the Cards dealt Rojas to the expansion Kansas City Royals for a minor league outfielder/third baseman, the wonderfully named Fred Rico.

The trade made little in the way of headlines, but it was a smart acquisition for the Royals. Rojas became their starting second baseman, stabilizing the infield for a young, inexperienced team. Yet, Rojas faced a dilemma. With his wife ill, he considered retiring after the 1970 season so that he could tend to her health needs.

Thankfully, his wife’s health improved. Rojas decided to remain a Royal. In 1971, Rojas would put together his finest offensive season, batting an even .300 while reaching career highs in on-base percentage (.357) and slugging percentage (.406). He also teamed with Freddie Patek, the Royals’ new starting shortstop. Not only did Rojas make the American League All-Star team, but he also received some consideration in the league’s MVP race, finishing 14th in the voting.

Over the next three seasons, Rojas remained a solid contributor, hitting in the .260 to .270 range and earning selection to three consecutive All-Star games. On a local level, Rojas became one of the most popular members of the Royals, attracting fans with his hustle, his steady fielding, and his ability to put the ball in play. He started to gain some national attention, too, especially in the 1972 All-Star Game. Summoned as a pinch-hitter by Earl Weaver, Rojas proceeded to deliver a pinch-hit home run.

Roja’ overall game did not start to show significant decline until 1975, when his batting average fell to .254. The following summer, he gave way to a young Frank White, a second baseman with more range and power than Rojas. Ever the team player, Rojas did not create waves. He accepted a role as a utility player and offered White the benefit of his decade and a half worth of experience in the major leagues. Rojas also added to his popularity when the Royals clinched the American League West that summer. Fans cheered as he and Patek jumped into the fountains located beyond the outfield fence at Royals Stadium.

Rojas would play one more season in Kansas City. In October of 1977, the Royals released the aging infielder, who had announced his retirement. Rojas became the first base coach for the Chicago Cubs, who actually activated him as a player in September of 1978. As it turned out, Rojas never played in a game for the Cubs. At the end of the ’78 season, Rojas called it quits for good, ending his big league career 16 years after it had begun.

Rojas continued to coach and scout with the Cubs, before eventually working as a coach with the California Angels. For a brief time, he became the Angels manager; he forged a record of close to .500, but the Angels fired him with two weeks remaining in the season. From there, he took a job with the Angels as an advanced scout, and then served coaching stints with the Florida Marlins, New York Mets, and Toronto Blue Jays.

Once his on-field career ended, the well-spoken Rojas turned to announcing. He became a Spanish-language broadcaster for the Marlins.

I have heard Rojas interviewed a number of times – he is nearly as proficient in English as he is in Spanish – and have always found him to be enlightening, insightful, and passionate about the game. I can see why Gene Mauch liked him so much. Clearly, this is a man who knows the game inside and out, and who used that knowledge to help him overachieve as a major league player.

If you ever have the chance to listen to Cookie Rojas talk baseball, don’t let the opportunity pass you by.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

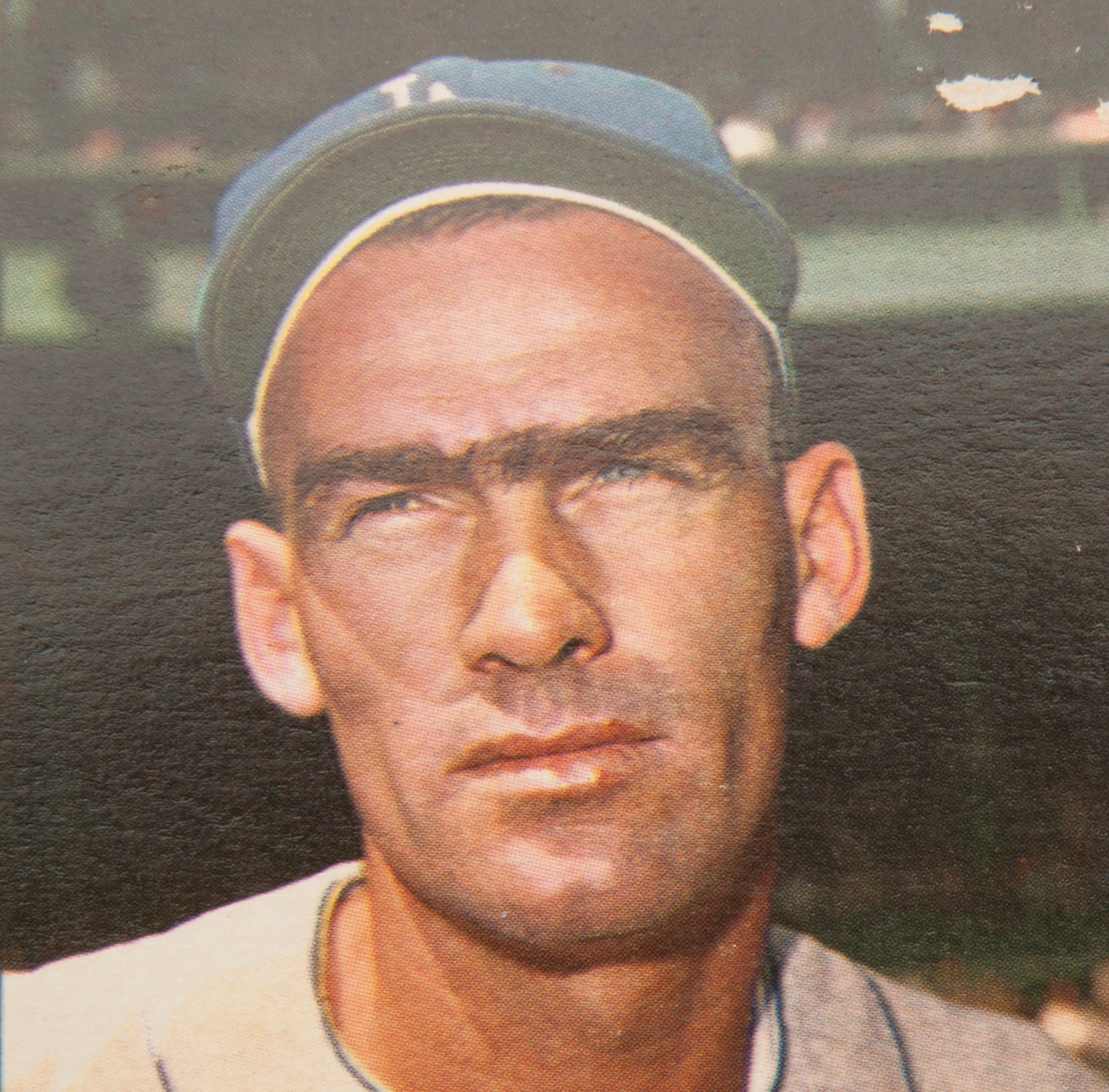

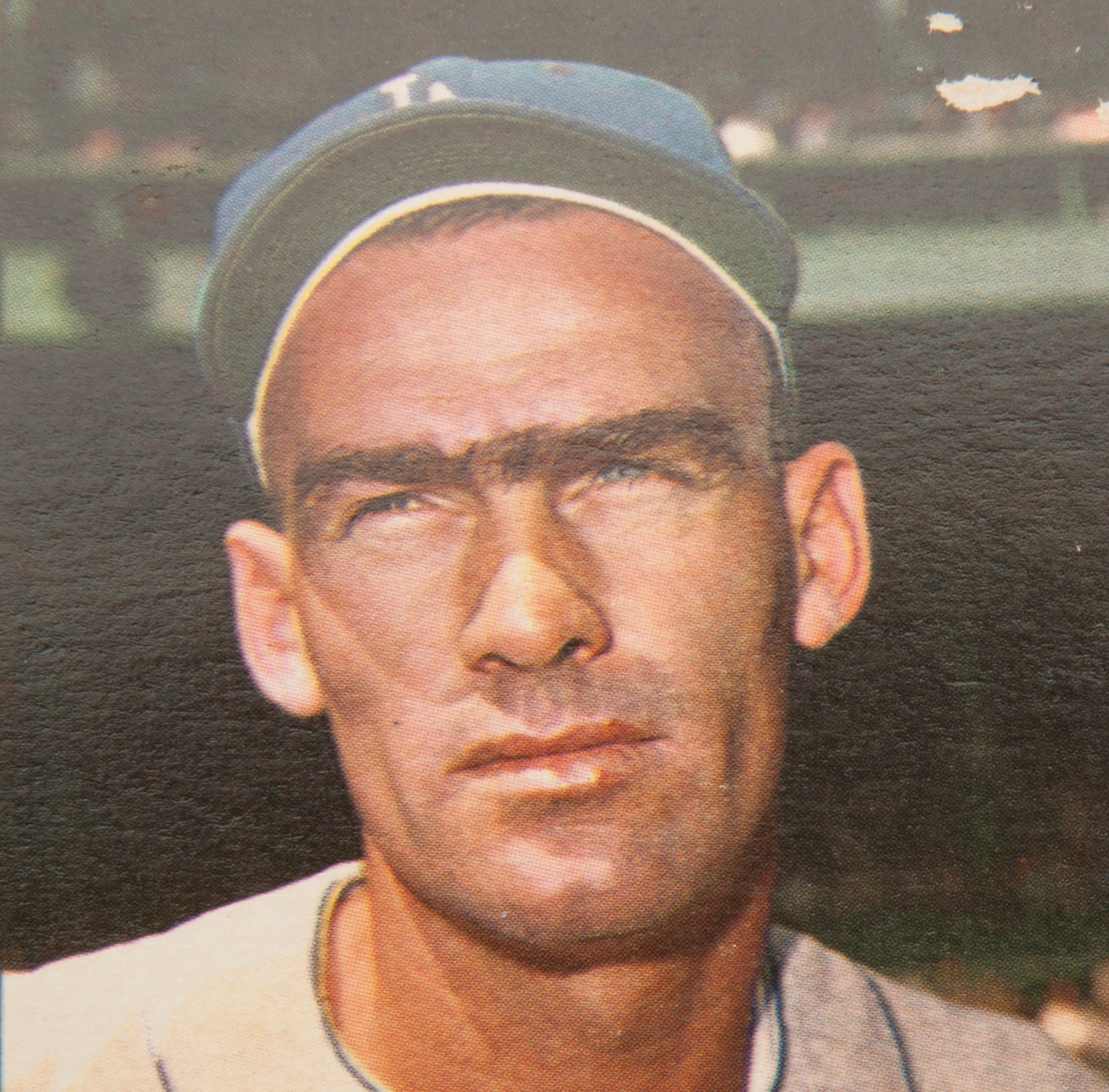

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

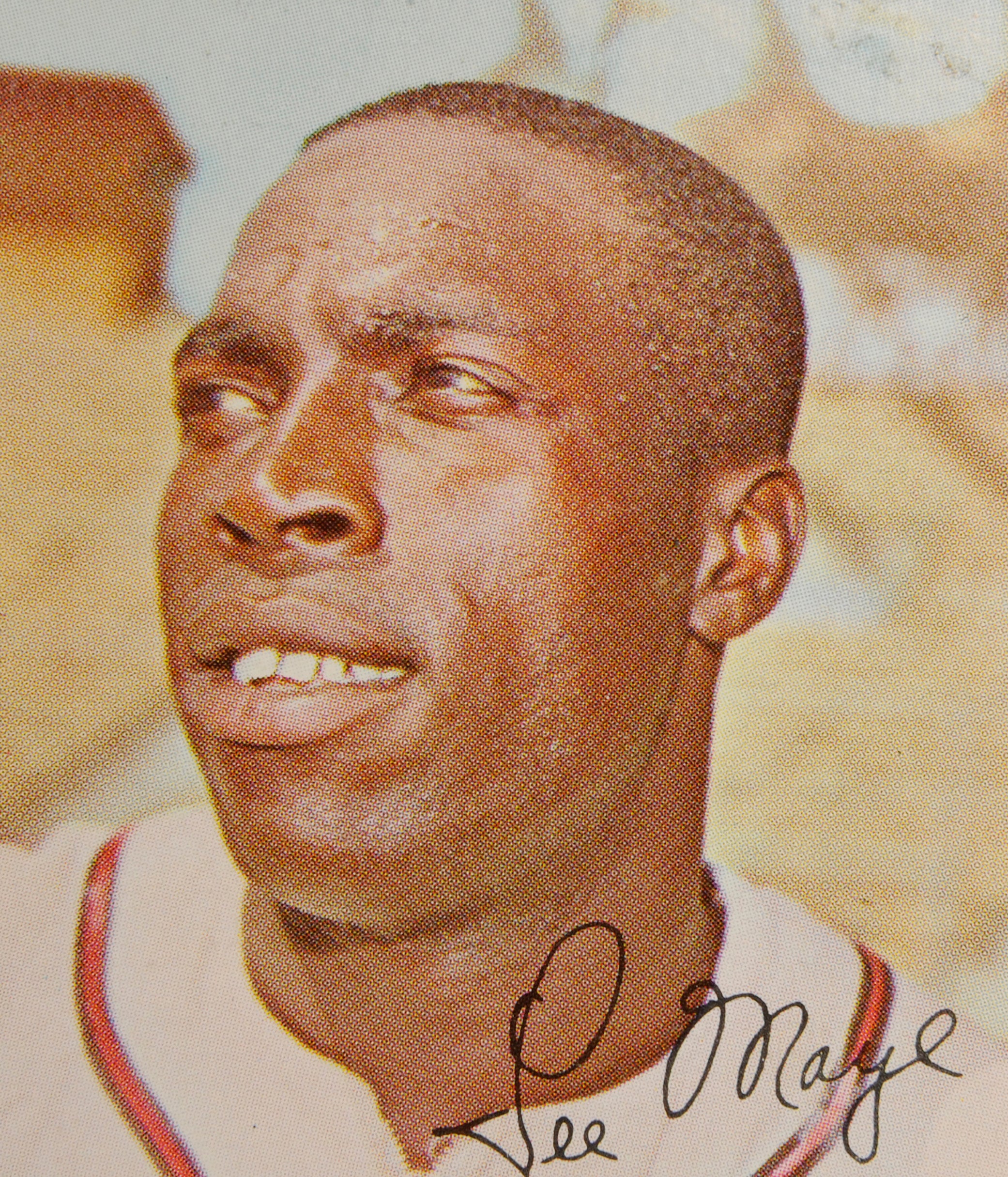

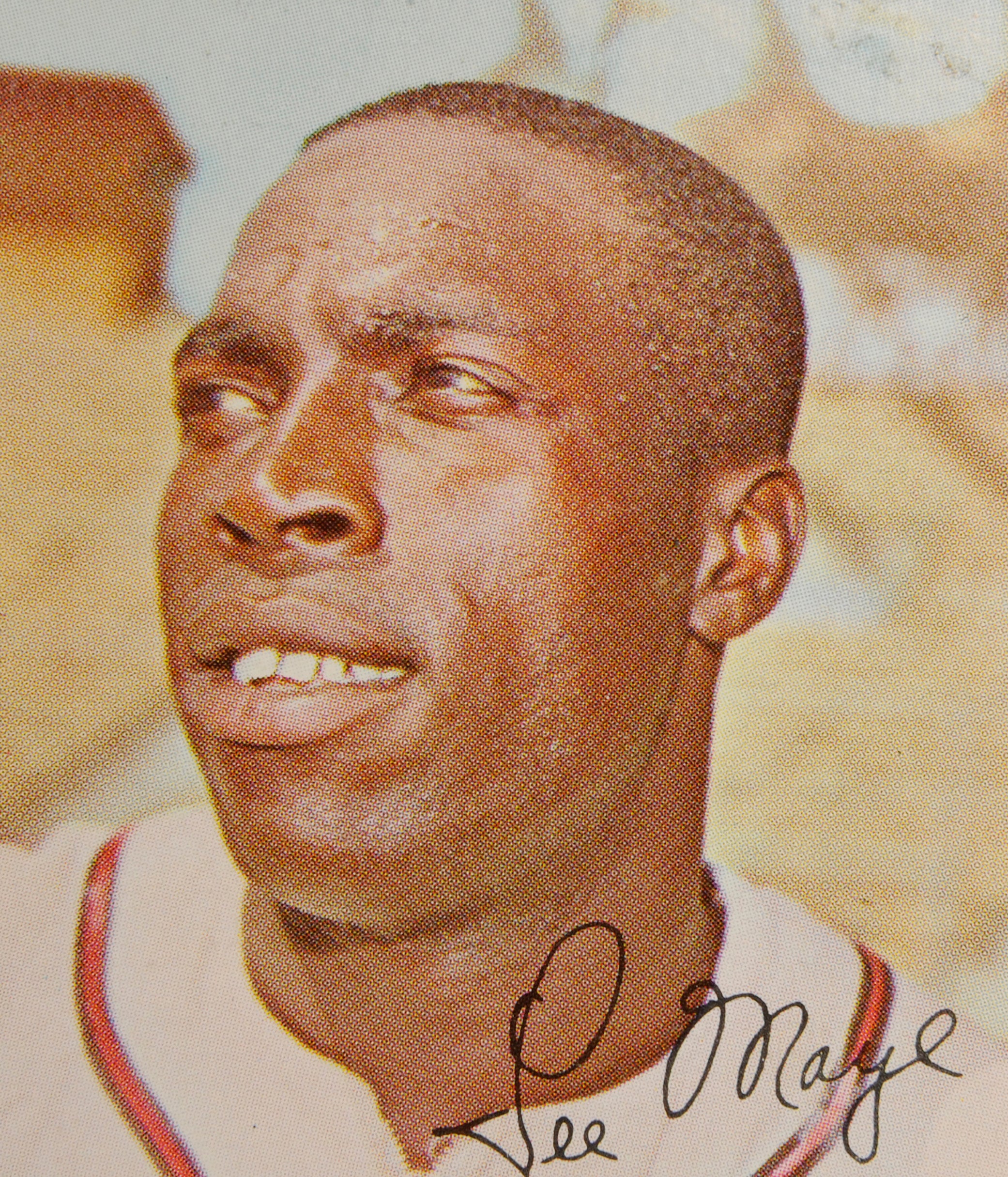

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

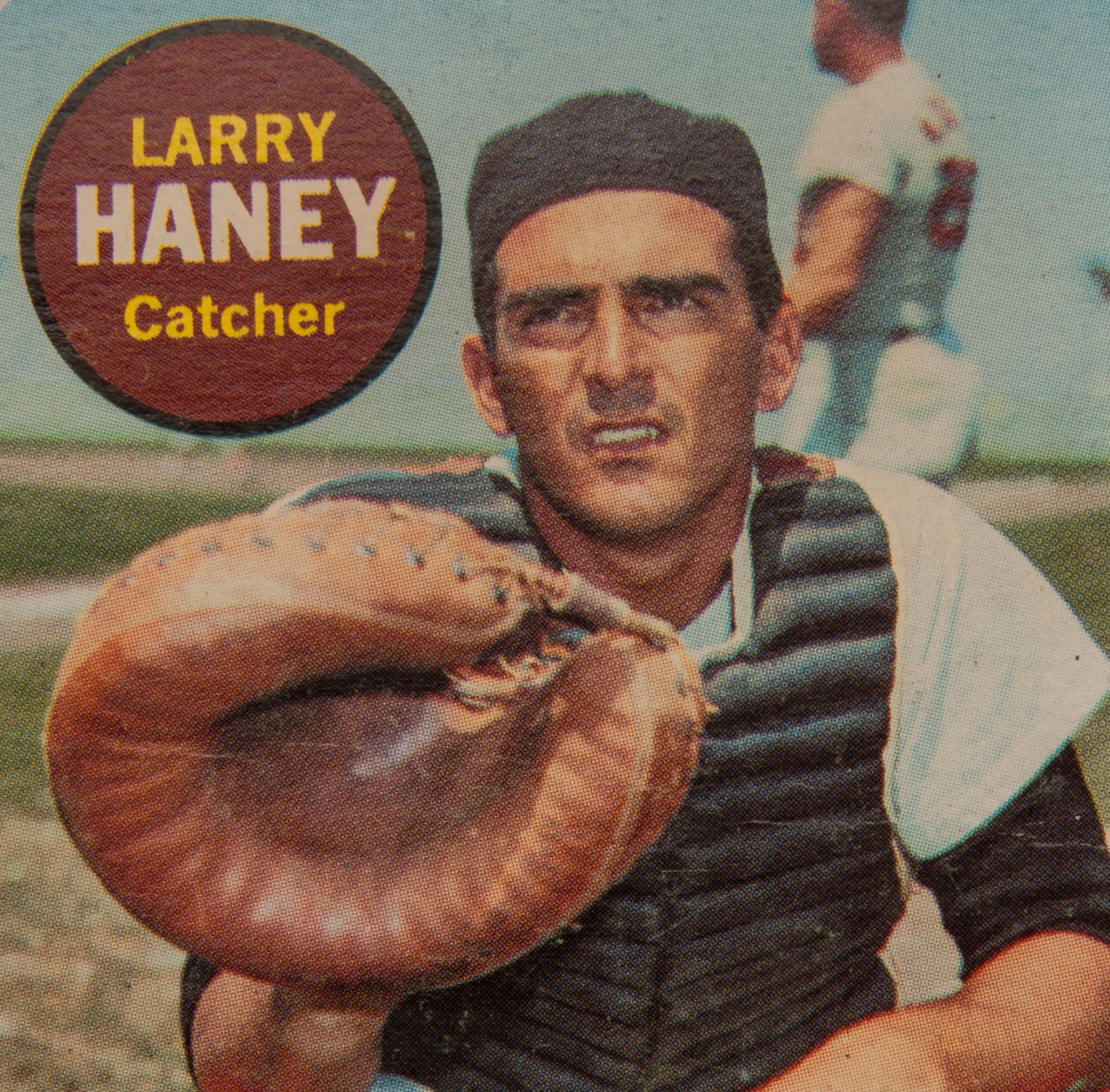

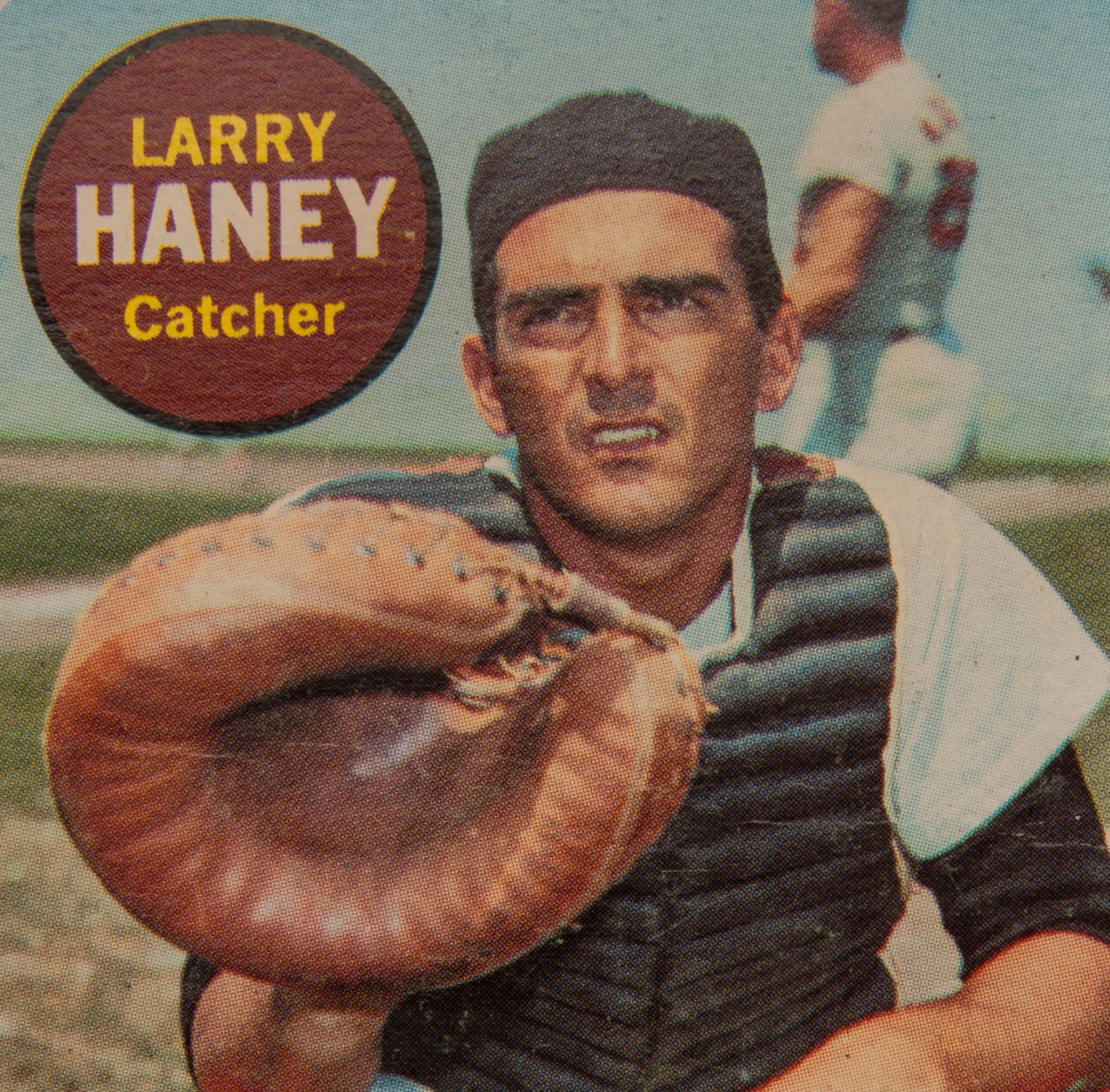

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

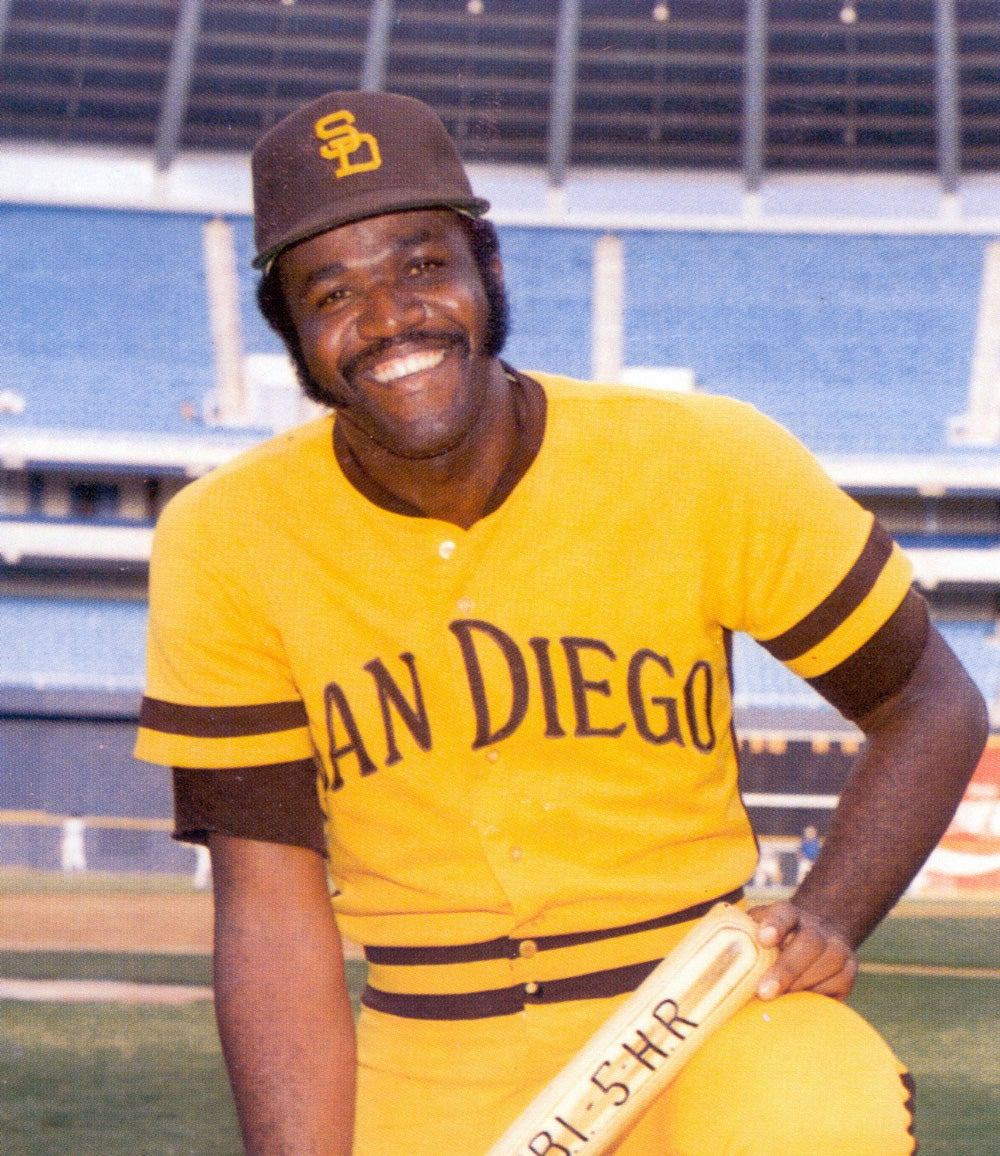

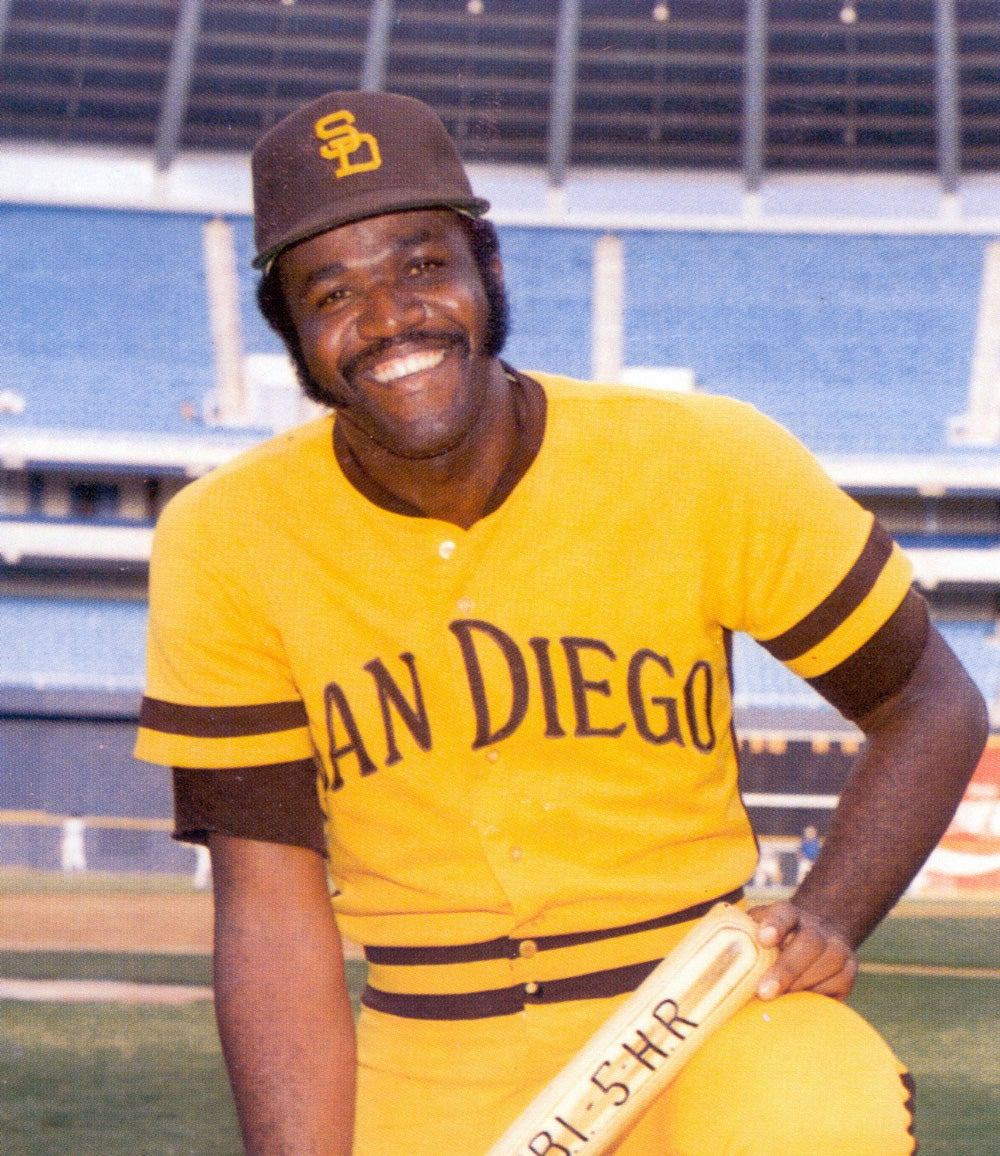

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney