- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Rich Rollins

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Rich Rollins

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

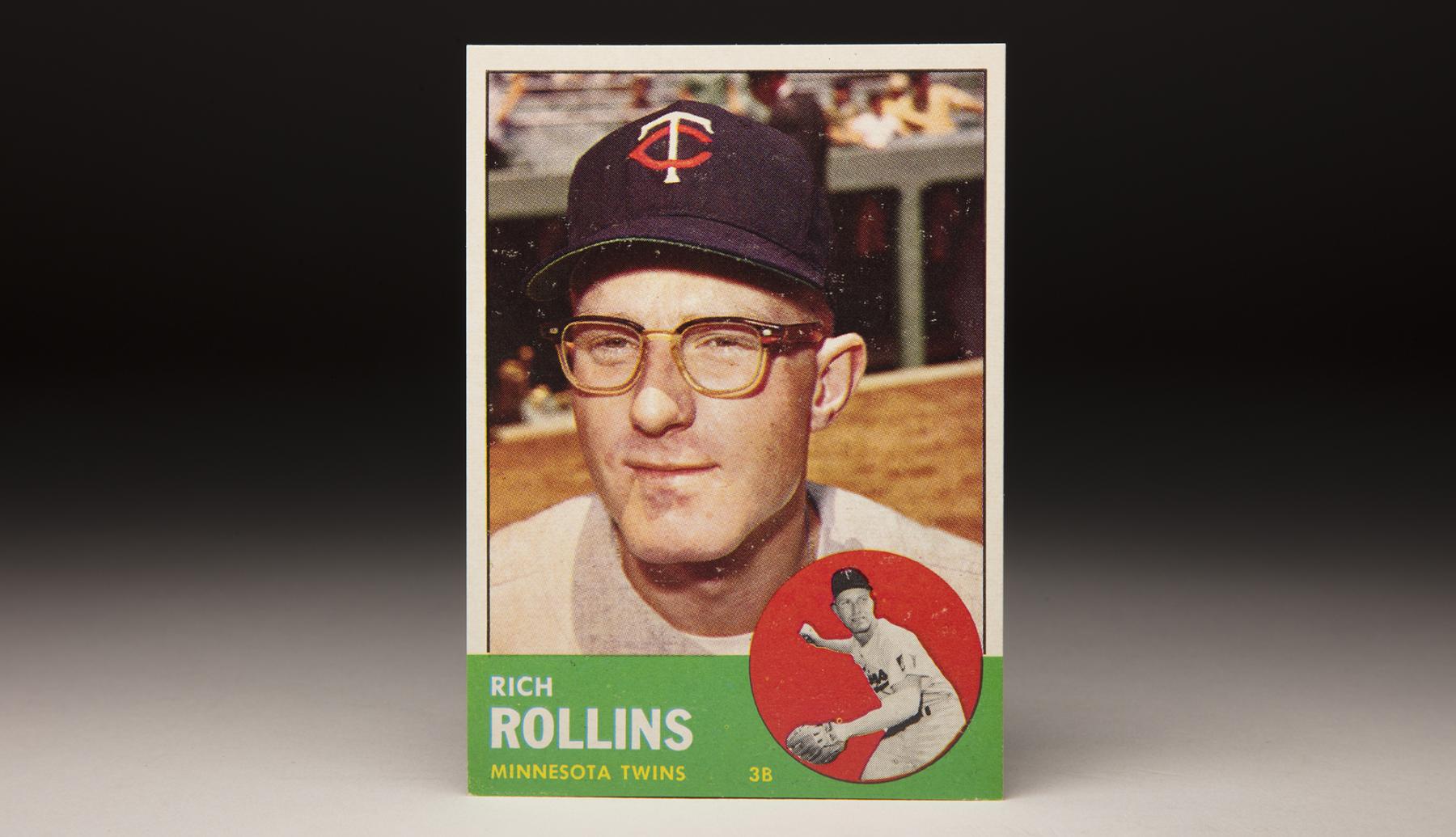

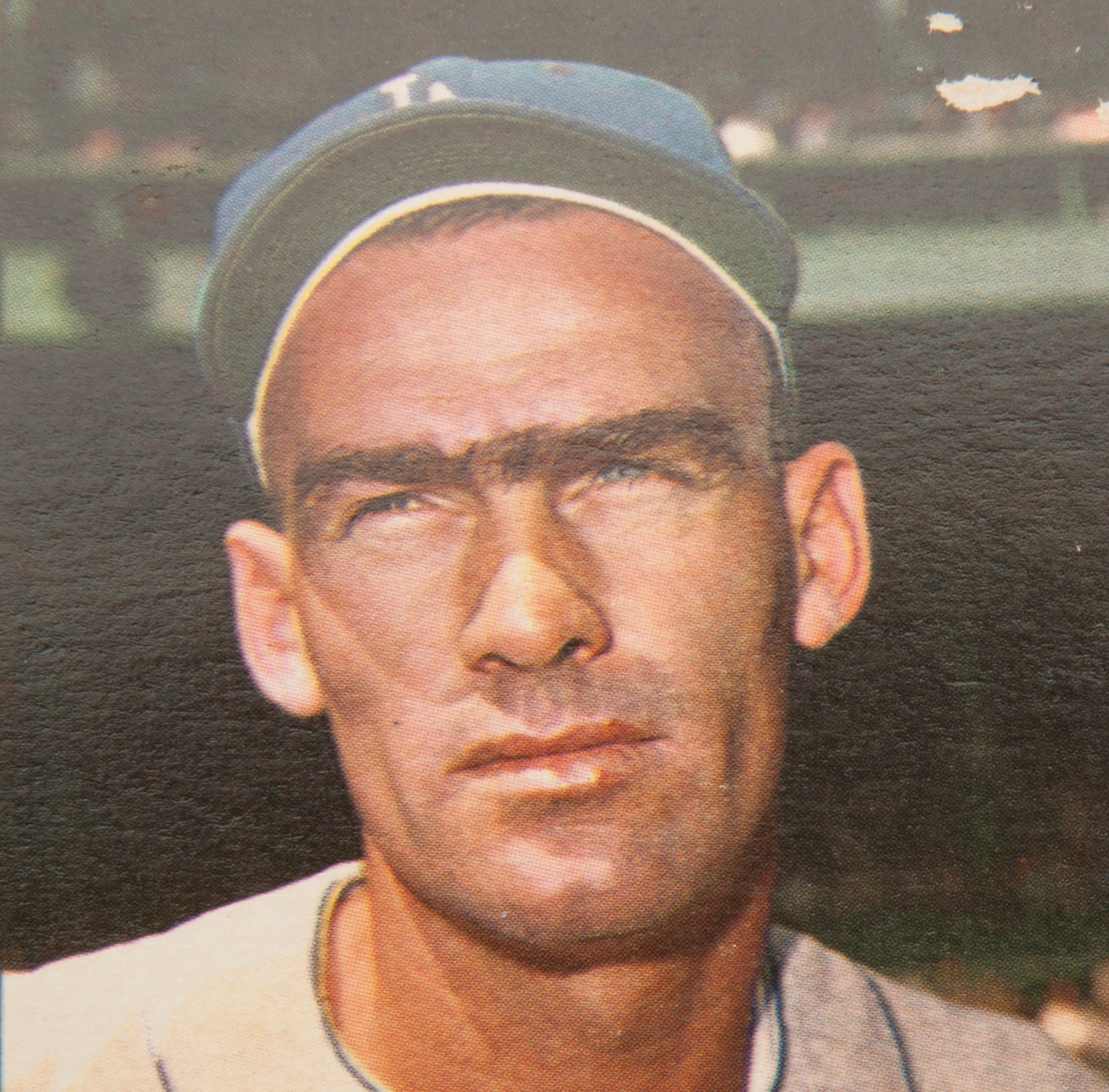

While I often used to confuse him with Rich Reese, his onetime teammate with the Minnesota Twins, it’s always been easy to pick out Rich Rollins in a stack of 1960s baseball cards. Just find the guy with the red hair and the big horn-rimmed glasses seemingly taken straight from a trailer for the 1984 comedy classic, Revenge of the Nerds, and you’ve got yourself another cardboard gem depicting the player they called “Red” Rollins. Some players from the 1960s wore dark sunglasses, like Ryne Duren and Eli Grba, giving them the look of tough, law enforcement types. Some wore clear, wireframe glasses, which were starting to gain in popularity and gave off more of a studious look. And then there were the players like Rollins who decided that the pointy, awkward horn-rims were the way to go.

By the mid-1970s, such glasses were so out of fashion as to be mocked (as if we made any better fashion choices by that time), but Rollins and a few other players, including Steve Blass and Denny McLain, proudly wore that style of spectacle in posing for their cards. Blass and McLain sported the glasses only occasionally, and not while actually pitching, but Rollins wore the glasses on many of his Topps cards and while he actually played. In later years, he adopted glasses with very dark frames, which only accentuated the old-fashioned feel of his cards.

In addition to the glasses, Rollins sports a baby-faced quality on his 1963 Topps card. Completely clean shaven and with soft features, he looks younger than his actual age of 24, when this photograph was taken during the 1962 season. (Based on the road jersey that he is wearing, it’s likely that the photo was snapped at an American League road venue.) Without his cap and uniform name on his jersey, it might have been easy to mistake him for one of the Minnesota Twins ballboys. Rollins’ face and expression make him appear especially innocent, more like an intellectual college professor than a stereotypical rough-and-tumble ballplayer from the early 1960s.

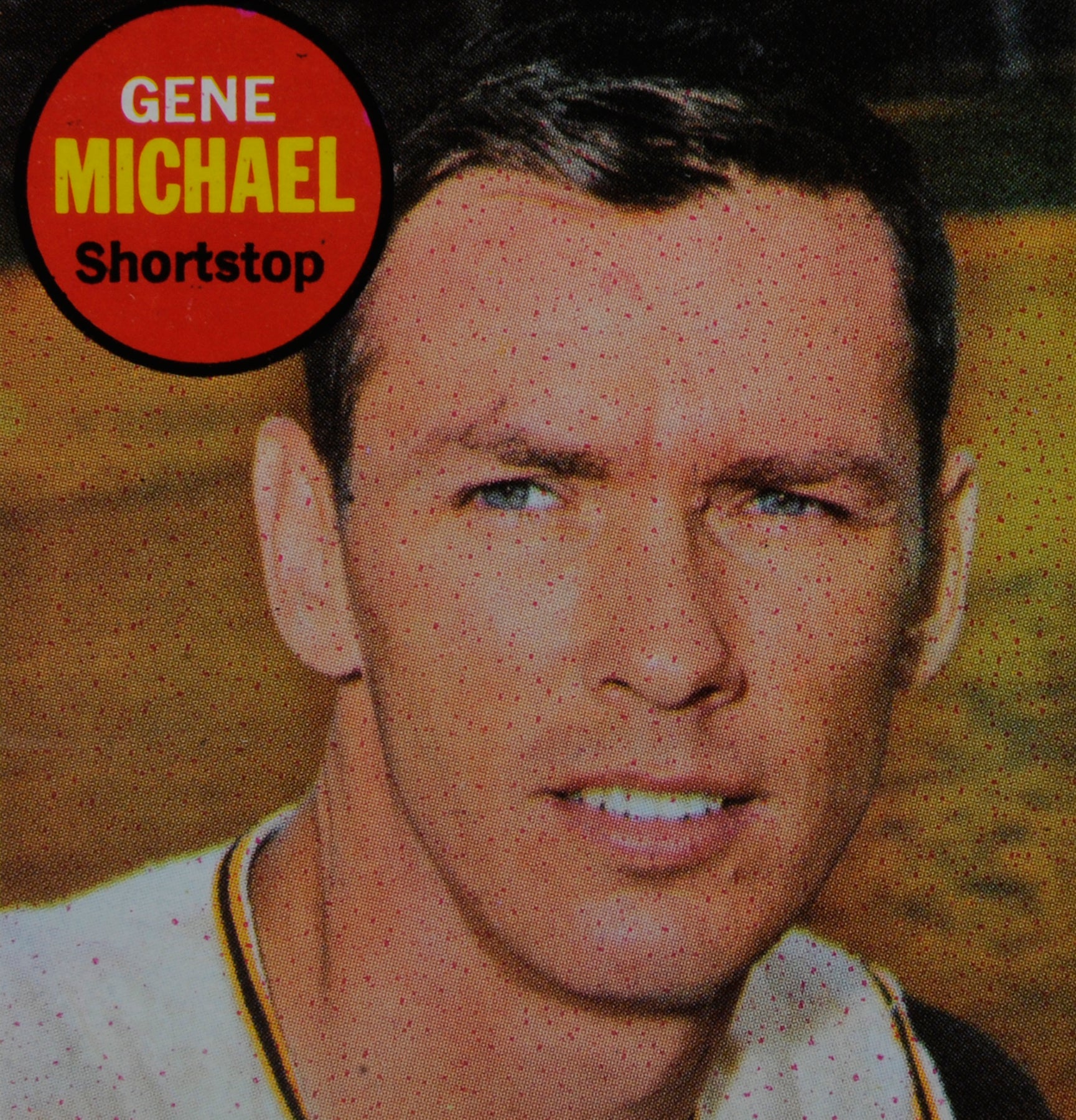

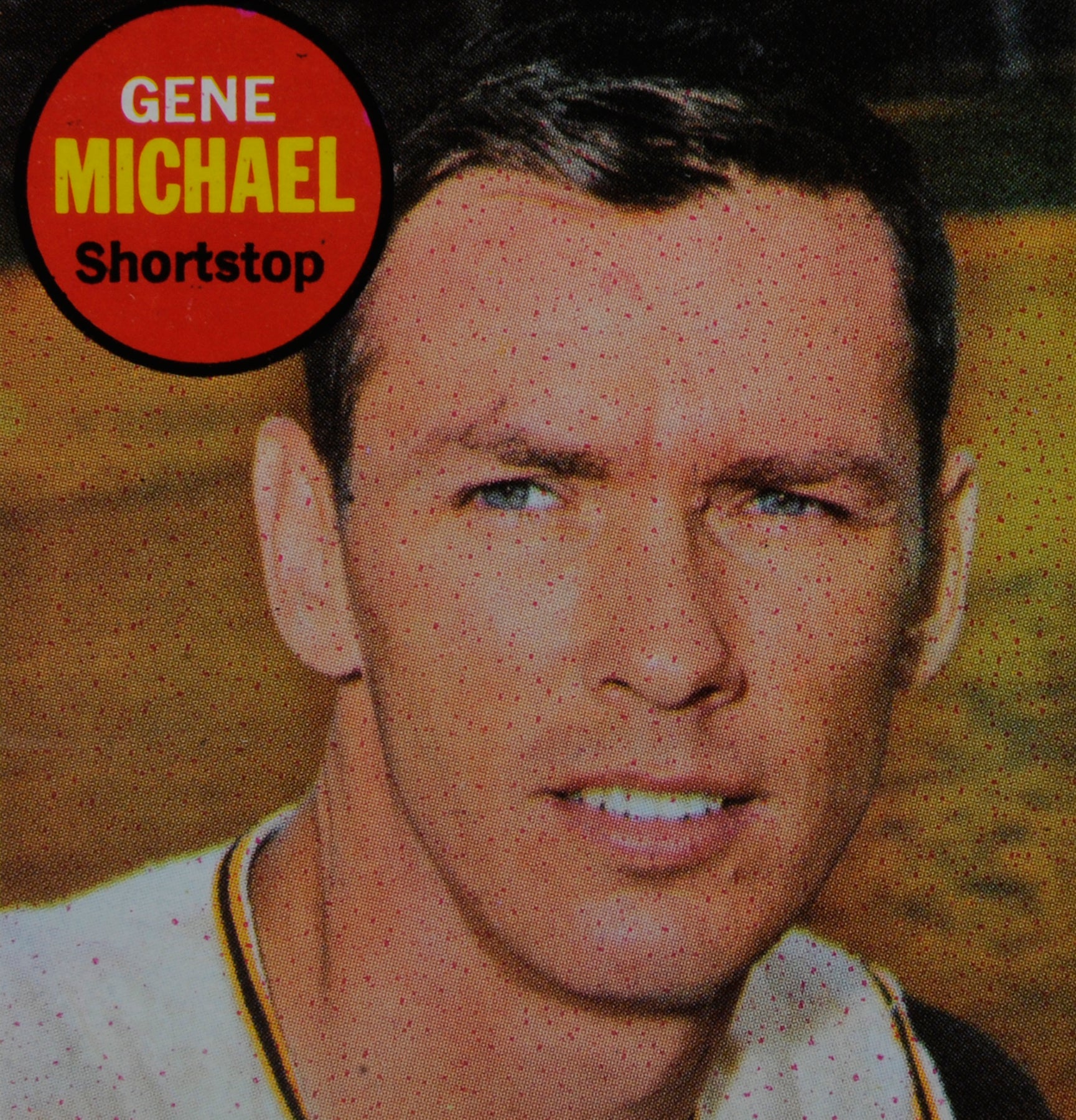

In actuality, Rollins did possess high intelligence, along with a remarkable work ethic. A star second baseman at Kent State University, he teamed with another future major leaguer, Gene Michael, to form one of the best double play combinations in the land. As well as Rollins played for Kent State, he drew the attention of only one major league team: The old Washington Senators.

“I took a whole lot of criticism. I was small, I wore glasses, I was bowlegged, I couldn’t run good,” Rollins recalled in an interview for the web site, twinstrivia.com.

While Rollins lacked the pure athletic skills of other prospects, his intangibles clearly pushed him into the category of a prospect. One of Washington’s scouts, Floyd Baker, invited Rollins to a tryout at Griffith Stadium in June of 1960. It was there that Rollins impressed Baker with both his willingness to work and an exemplary attitude. On Baker’s strong recommendation, the Senators signed Rollins to his first professional contract.

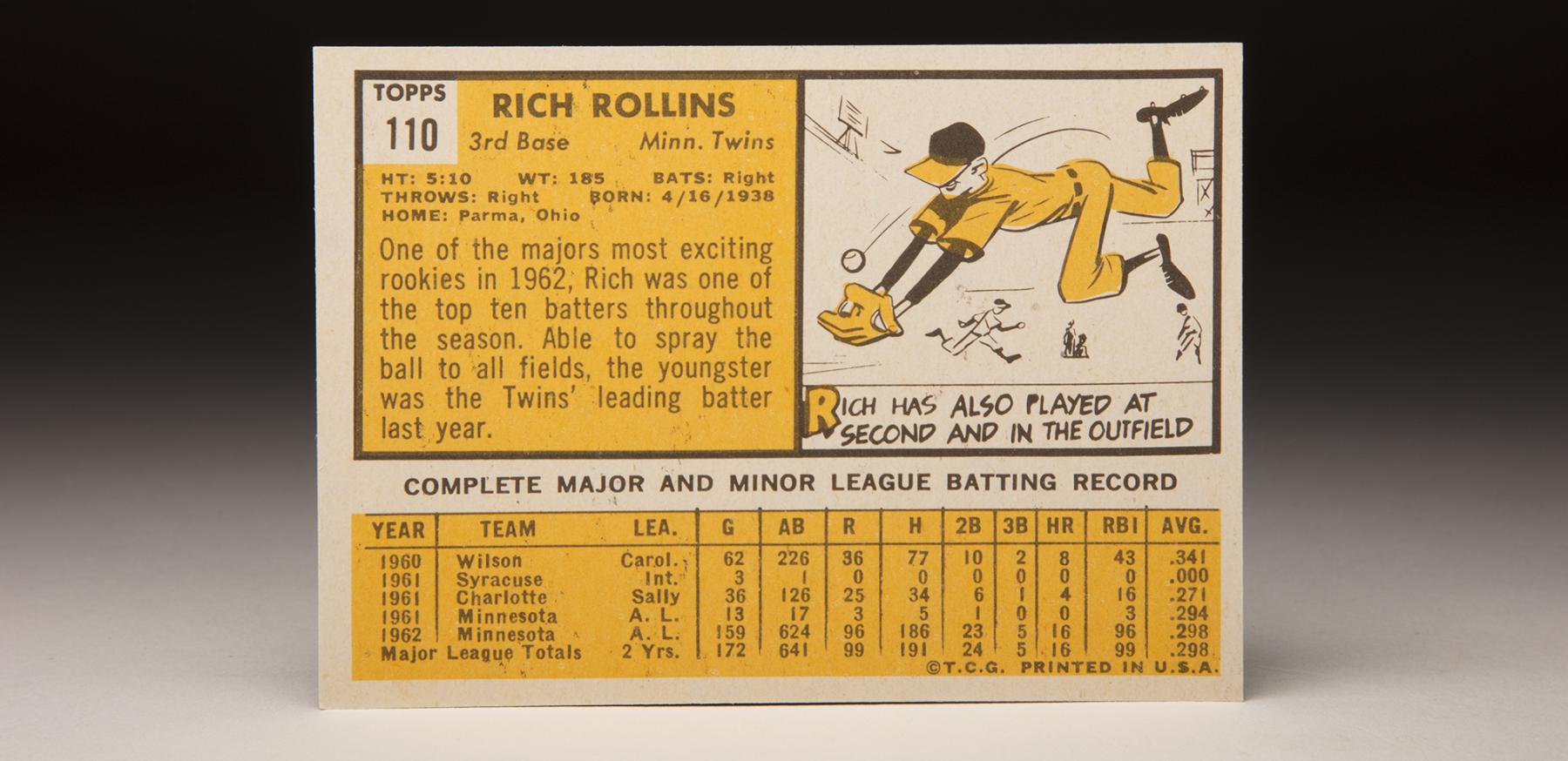

The Senators assigned Rollins to their Class B affiliate at Wilson, a team in the Carolina League. Playing for future big league manager Jack McKeon, Rollins excelled at the plate. He hit .341 in 62 games. To this day, Rollins credits McKeon for giving him the chance to play on a team overloaded with infielders.

That winter, the Senators moved to Minnesota and became known as the Twins. In the meantime, Rollins served time in the U.S. Army. He put on a significant amount of weight, increasing from 185 to 200 pounds that winter. Despite the weight gain, the Twins assigned him to Triple-A Syracuse to start the 1961 season. But he hardly played during the first few weeks of the season. Concerned that his skills were going to waste, the Twins reassigned him to Charlotte of the Class A South Atlantic League. Rollins hit a respectable .270, while learning a new position: Third base. Each day, Rollins took at least 100 ground balls hit by his manager, Ellis Clary.

After only 32 games at third base, the Twins called up Rollins. He made his major league debut on June 16, facing Hall of Famer Early Wynn, but totaled only 17 at-bats for the season. Though he rarely played as a rookie, Rollins used the time as a learning experience. He also endured criticism from a veteran teammate, Billy Martin, who happened to be playing his final season.

Martin rode Rollins hard, telling him that he would never be good enough defensively to stay in the major leagues. As a result of the criticism, Rollins and Martin argued repeatedly. At one point, Rollins became so upset with Martin’s taunts that he became tempted to punch him. Fortunately, the level-headed Rollins thought better of it.

As it turned out, Martin actually liked Rollins. Martin later told Rollins’ father that he rode his son so hard because he felt that he did have the talent to play in the major leagues. It was Martin’s old-school way of trying to make Rollins better.

Perhaps Martin’s rough treatment of Rollins paid off. During Spring Training in 1962, the Twins lost the top three shortstops on their depth chart to injury, necessitating that Rollins play the position. Though he had never played shortstop professionally, Rollins filled in well. He also batted over .400 in Grapefruit League play. When Zoilo Versalles returned to the starting lineup at shortstop, the Twins made Rollins their everyday third baseman.

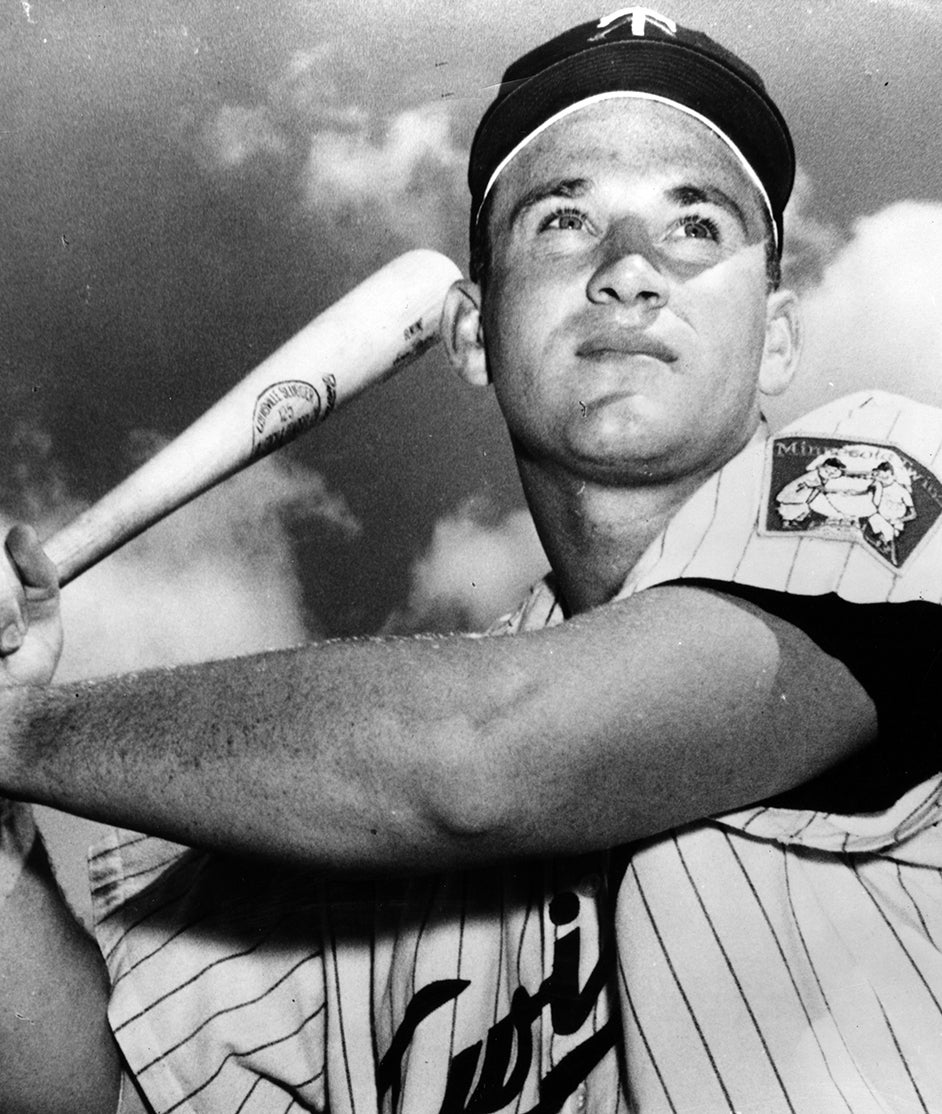

Rollins excelled for the Twins. Despite chatter among scouts that he couldn’t hit the curveball, he batted .296, ripped 16 home runs and earned a spot on both of the American League All-Star teams. (Back then, the American and National leagues played two mid-season games.) At season’s end, Rollins received strong consideration for league MVP. He finished eighth in the voting, placing higher than any Twins player in the balloting. The season turned out to be even more prosperous because of a personal meeting. Rollins met his future wife, Lynn Maher, a stewardess with United Airlines. They would marry in February of 1963.

Shortly after the ceremony, Rollins reported to Spring Training. He suffered an early setback when he was hit in the face by a pitch from Tigers’ right-hander Paul Foytack. The incident left him with a fractured jaw, which he had to have wired shut. Surviving mostly on a diet of liquids and baby food, Rollins lost weight and could not make his 1963 debut until April 20. Despite the injury, Rollins played well. He once again hit 16 home runs, raised his batting average to .307 and improved his OPS by a point.

Much like another young third baseman of the era, Chicago’s Pete Ward, Rollins seemed headed toward a career of stardom. Then came the spring of 1964, when a calcium deposit in his hip began to bother him. Rollins sought treatment at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., but the condition affected him throughout the summer. Rollins’ batting average dipped to .270 and his home run total fell to 12. He also committed 24 errors, many at inopportune times. Clearly, he did not have the impact of his first two full seasons.

Rollins would struggle to match even his modest numbers of 1964 again. In 1965, Rollins dropped nearly 25 pounds, but the weight loss did not help his play. He slumped terribly, hitting only .249 with five home runs. While Rollins’ level of play dipped, the Twins as a team excelled, capturing the franchise’s first pennant since the move to the Twin Cities. By October, Rollins had lost his place in the starting lineup. Twins manager Sam Mele moved Harmon Killebrew to third base, creating a place for Don Mincher to play regularly at first base. During the World Series, Rollins came to bat only three times, all as a pinch-hitter, as the Twins lost to Los Angeles in seven tough games.

Rollins’ backup status continued in 1966. Killebrew started at third base early in the season. After recovering from a virus, Rollins moved back to third, with Killebrew shifting to left field. Rollins hit well in June, but then slumped during the second half of the season. He finished the year hitting .245, the worst average of his career to date. He did hit 10 home runs, but his slugging percentage remained below .400.

After the 1966 season, the Twins traded Mincher and moved Killebrew back to first base, clearing a path for Rollins to return to third. Thanks to a strong spring, Rollins won back the third base job, but once the regular season started, a wave of maladies hit. First, he injured his knee, sidelining him for three weeks. Even more importantly, his hip problem had become arthritic. And his knee remained an issue.

When Rollins played, he endured plenty of pain. He put up almost identical numbers to 1966, with his batting average again settling at .245. When the 1967 season came to a close, Rollins informed Twins owner Calvin Griffith that he wanted to retire due to the condition of his knee. Griffith asked him why. “Because I can’t take it anymore,” Rollins said, according to an article in the Sporting News. “It hurts too much.”

Griffith sat down with Rollins, asking him to reconsider. The owner convinced Rollins to make an appointment at the Mayo Clinic. There the doctors advised him to undergo surgery, so as to remove torn cartilage from his knee. Rollins agreed and went under the knife.

Rollins’ recovery did not proceed as planned. He developed an infection, which had to be treated during a follow-up visit. During Spring Training, the knee swelled up, causing Rollins additional pain. He also came down with intestinal flu, weakening him just before the start of the regular season. In June, he suffered an inch-long wound on a bad hop ground ball. Alternating between the starting lineup and a bench role, Rollins appeared in only 93 games and batted .241.

With the close of the ’68 season, Rollins’ time in Minnesota came to an end. He was now 30, and his body was betraying him. Realizing that his hip and knee conditions might only get worse, the Twins failed to protect him from the upcoming expansion draft. With their 26th pick, the fledgling Seattle Pilots selected Rollins from the Twins’ roster.

A strong spring performance in 1969 earned Rollins the Opening Day third base job. But knee and back problems took their toll, forcing him to undergo another surgery in July and effectively ending his season. Rollins would return to the team, by now transplanted to Milwaukee as the Brewers, in the spring of 1970, but soon lost his starting job to Tommy Harper. In May, the Brewers released him. Two weeks later, he signed with Cleveland, where he started only three games and came to bat fewer than 50 times. He also took on an unofficial role as a coach, but the Indians released him after the season.

Rollins believed that the Indians would retain him in some other capacity, but the front office informed him that the club had no openings at the time. “I am not surprised to be released [as a player],” Rollins told the Sporting News, “but I am disappointed because I thought I would be offered another job in the organization.” Two years later, Rollins did return to the Indians’ organization as an instructor and scout. Later on, he became the Indians’ director of group sales before switching sports, taking a job with the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers as part of their ticket sales department. Retiring in 1993, Rollins continues to live in Akron, Ohio, not far from where he grew up.

With his awkward glasses and soft features in full evidence on his Topps card, Rollins looked like anything but the typical ballplayer of 1960s vintage. He lacked the natural athletic skills of the players who became stars. But his smarts, his work ethic and his easygoing personality allowed him to forge out a 10-year career in the big leagues, along with a successful second career in the front offices of two professional sports teams. Rollins’ success should teach us to never underestimate the staying power of the kid with the big glasses.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

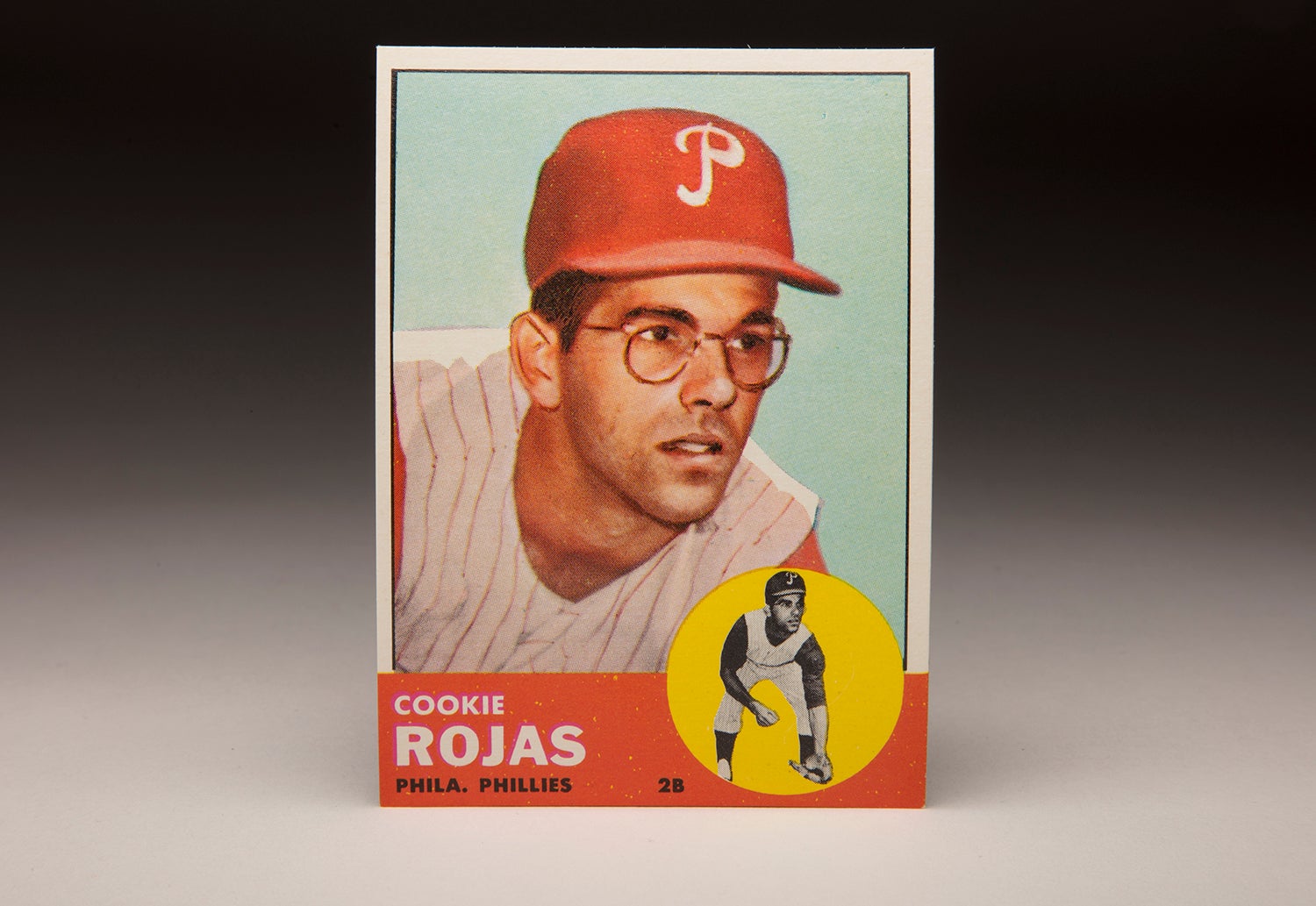

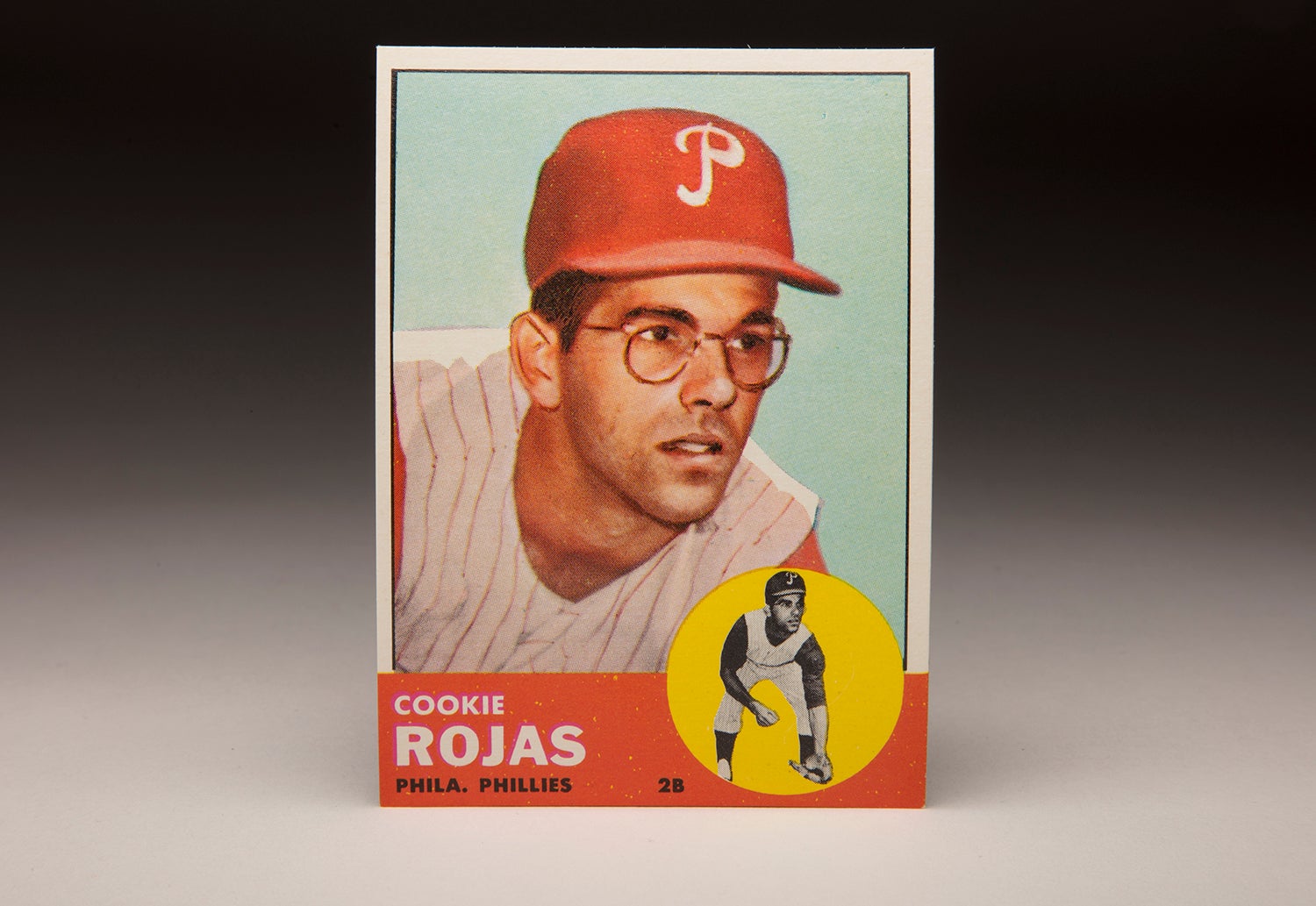

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

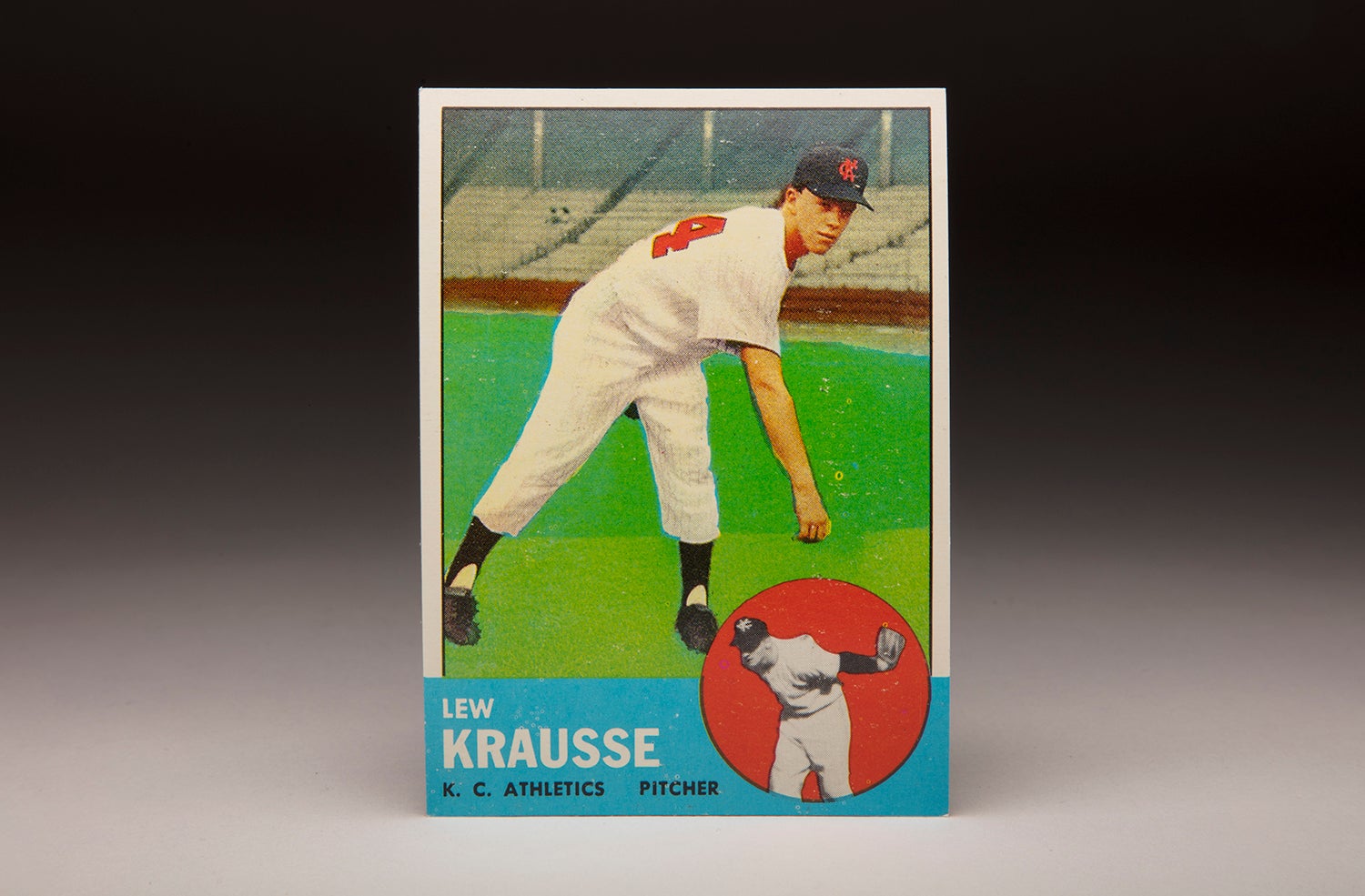

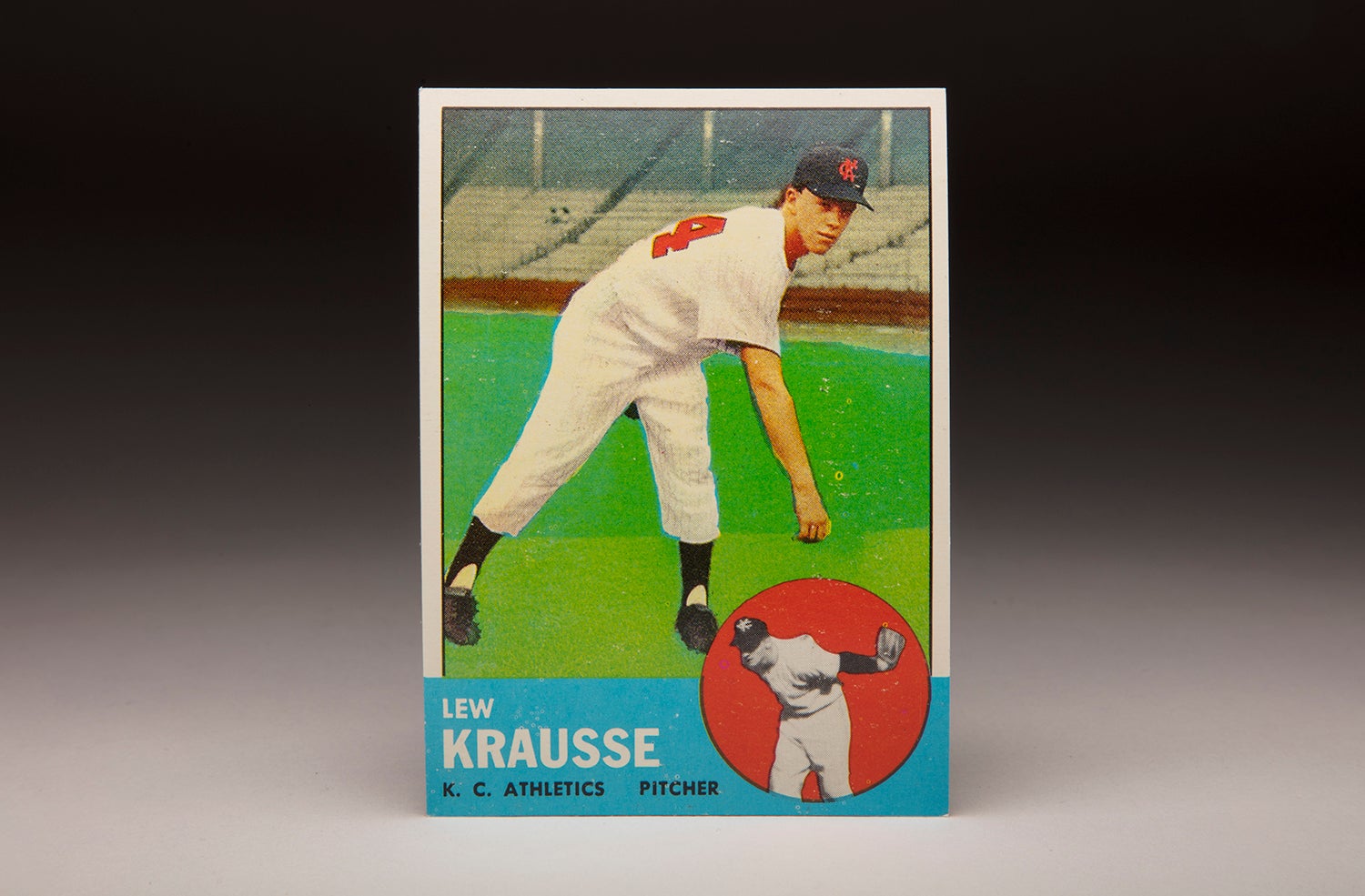

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Lew Krausse

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Lew Krausse

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon