- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Lew Krausse

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Lew Krausse

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

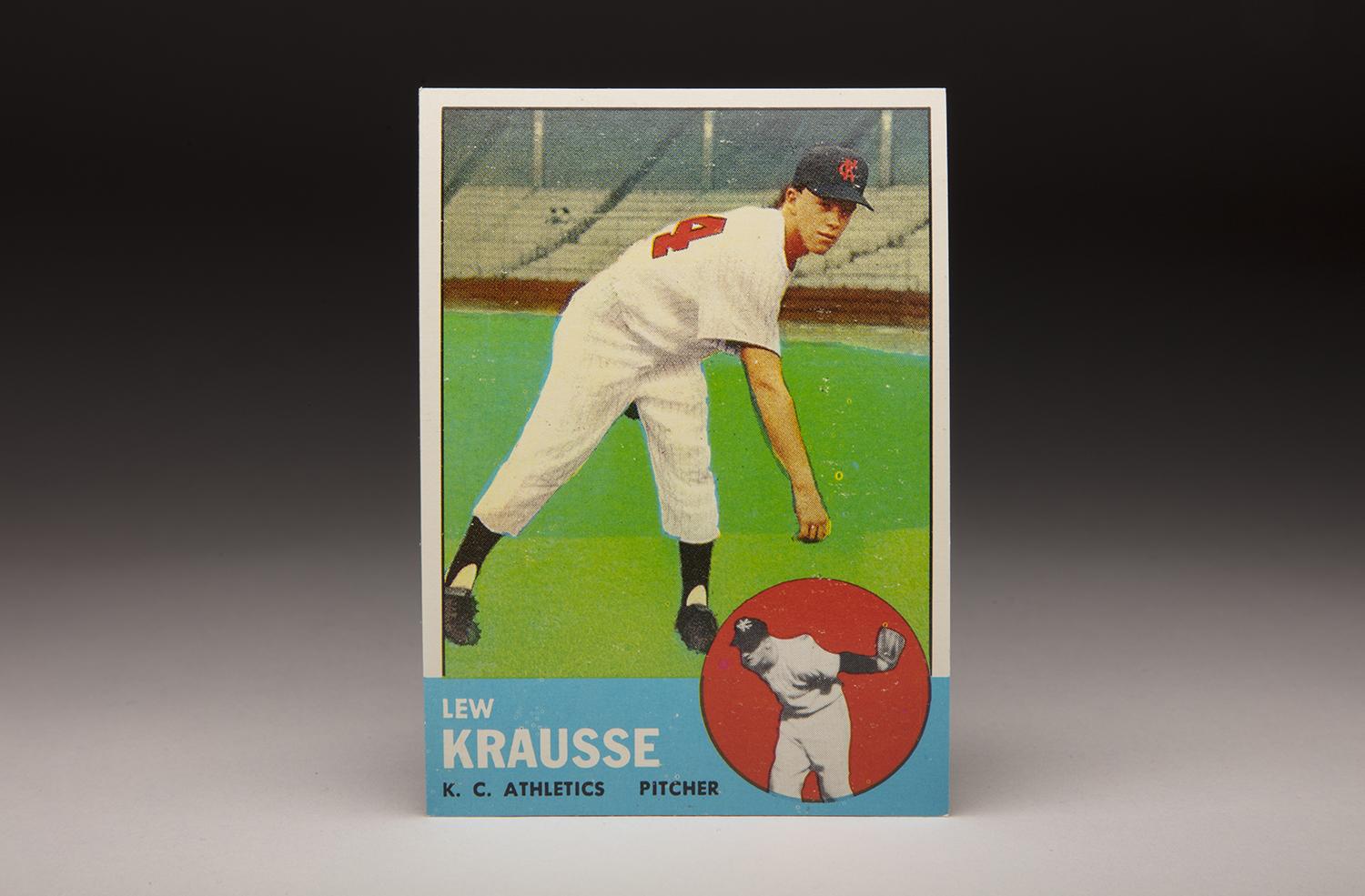

There is nothing normal about Lew Krausse’s 1963 Topps rookie card.

First, it appears that all of Krausse’s Kansas City A’s uniform has been airbrushed, based on the lack of definition to the pinstripes and the strange brightness of the No. 4 on the back of his jersey. Beyond that, it appears that the playing field and the stadium grandstand, presumably at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City, have also been airbrushed, too. Notice the strange two-tone nature of the grass, which is a lighter green in the area near Krausse but a darker green behind him. The grass doesn’t really look like grass at all; it looks more like artificial turf, which was not yet used in the big leagues at that time.

Furthermore, there is a stunning lack of detail to the grandstand, which gives off the impression that it too is airbrushed, or perhaps simply drawn from scratch. It looks more like a painting than a photograph.

Finally, there is the odd perspective to the card. Is Krausse actually standing on the grass, or is he floating above it? It’s hard to tell. Initially I thought that entire card was a painting, one that was created by an artist still trying to master the techniques of perspective and three-dimensionality. Simply put, the card appears odd in every way, shape, and form.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In searching for some answers to the mystery behind this card, I happened to see a 1964 card of Krausse. It looks eerily similar to the 1963 version. This time, the airbrushing has been removed, so that the grass and the grandstand look normal. The colors of Krausse’s uniform are duller, but look more realistic. It is quite evident that this was the original photograph that Topps used for the basis of the ’63 card.

Of course, this doesn’t answer the question as to why Topps felt compelled to use so much airbrushing on the card to begin with. The original photograph, which is a little dull but decent enough, did not really need to be touched up at all. My only theory is that Topps was trying to do something creative and bold, in an abstract art kind of way, in an effort to make the card look brighter and gaudier. If that was the goal of the Topps artists, they certainly succeeded.

The offbeat and unusual nature of Krausse’s rookie Topps card matches the nature of his story. The son of the former major league pitcher who bore the same name, Krausse became a sensation as far back as Chester High School in Chester, Pa., where he drew the attention of numerous scouts in the early 1960s. As a high school pitcher, Krausse threw a whopping 18 no-hitters.

Krausse’s high school domination resulted in a flood of scouts descending on the small city of Chester. A bidding war resulted during the early the early summer of 1961, one that Kansas City Athletics owner Charlie Finley became determined to win. At a time when other amateur stars were securing large bonuses, like the $175,000 that went to Bob Bailey, Finley went as high as $125,000 in his effort to woo Krausse. That turned out to be the winning bid, ensuring that Krausse would make his major league debut for the A’s.

Krausse’s contract contained an unusual stipulation: A guarantee that he would pitch in the major leagues. On June 16, only three weeks after his signing, Finley and the A’s fulfilled that guarantee. Without the benefit of a single day in the minor leagues, Krausse went straight from high school to the big leagues, facing the expansion Los Angeles Angels. A crowd of more than 25,000 fans, a remarkable total for a franchise that did not draw many followers, welcomed Krausse to the major leagues. Those in attendance on the hot, humid night were not disappointed. They watched Krausse dominate the Angels over nine innings. Allowing only three hits while working around five walks, Krausse pitched a complete game shutout – good for a 4-0 win over LA.

On the surface, Krausse seemed headed for an impressive rookie season. Yet, some circumstances of his debut need to be underscored. The Angels, as an expansion team, did not feature a star-studded lineup. They also had little to go on in terms of an extensive scouting report on Krausse. Those factors worked in his favor. But after that debut, reality set in for the youthful right-hander. Although he continued to draw large crowds, Krausse won only one of his next six decisions, finishing his rookie year with an ERA of 4.81.

Krausse threw as hard as most right-handers in the American League, but his lack of control remained the primary setback. For that Krausse took the blame. “After [my debut], I started trying to throw too hard. I got real wild.” As a rookie, he walked 46 batters in 55 innings. Finley and the A’s realized that he needed more time – perhaps a significant amount – in the minor leagues.

The A’s sent Krausse back to the minor leagues for the next two full seasons. In his minor league debut for Binghamton, he struck out 16 batters, leading to speculation of a quick return to Kansas City. But Krausse developed a sore elbow with Binghamton in July of 1962, forcing the A’s to shut him down for the balance of the season. In November, an examination at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota determined that he would need elbow surgery, which was regarded as a risky procedure for any pitcher of that era.

The elbow problems should not have surprised the A’s. At the time of his signing in 1961, a doctor had examined Krausse’s arm, noting that it looked like that of 25-year-old man, rather than that of a teenager. Concerned that Krausse has been subject to overuse as an amateur, the doctor wondered how long a career Krausse would be able to have. Apparently, Finley either ignored the doctor’s observation or simply didn’t know about it.

Once recovered from the surgery, Krausse earned a promotion to Triple-A Portland of the Pacific Coast League in 1963. Given the PCL’s penchant for run-scoring, that proved a good test for Krausse. After a rocky start to the season, Krausse settled in and showed improved control, delivering a respectable ERA of 4.22 and winning 13 games.

Krausse opened the 1964 season with the A’s and made one start for them in April, but that turned into a disaster. He gave up four hits and three runs, retiring only one batter before being lifted by manager Eddie Lopat. From there, Krausse returned to the minor leagues, this time to Dallas, where the A’s had relocated their Triple-A franchise. Krausse again pitched creditably, but lost 19 games for a terrible Dallas Rangers team that was defeated 104 times. In September, the A’s gave him another look. He pitched well in one start, but struggled in three other outings, leaving the A’s wondering just how much progress he had made.

The 1965 season would represent another split summer for Krausse. He started the year at Triple-A Vancouver, where he spun an ERA of 3.22, a terrific number for the PCL. Then came another call-up to Kansas City. This time, he made seven appearances and showcased good control, but was otherwise hittable. At the end of his season, his ERA stood at 5.04.

The A’s encouraged Krausse to pitch in winter ball. He agreed, and reported to the Venezuelan League, where he dazzled. Nearly throwing a perfect game one day, he ended up with a pair of no-hitters and prepared to report to Spring Training.

The spring of 1966 represented a watershed moment for Krausse. Though Krausse was only 23, he was now out of minor league options. If the A’s didn’t include him on the Opening Day roster, they risked losing him to another team. Rumors circulated that the A’s might entertain trade offers for Krausse, which was once an unthinkable option.

Much to the delight of the A’s, Krausse carried the success of the winter league over to the regular season. On a staff that boasted of Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, Chuck Dobson and Jumbo Jim Nash, Krausse emerged as one of the most effective starters. Showing off a devastating curve ball that complemented his good fastball, he made 22 starts, won a team-high 14 games, and lowered his ERA to 2.99.

The 1966 season also brought some levity to the A’s, with Krausse, known as “Lew-Lew” to his teammates, unwittingly involved in the shenanigans. During a game in Kansas City, in which Jim Nash was dominating Baltimore, Krausse sat in the bullpen. The bullpen phone suddenly rang, with the voice on the other end instructing Krausse to begin warming up. When Nash saw Krausse begin to stir in the bullpen, he became rattled on the mound, wondering why there was a need for a reliever to start working. It turns out that the call had not been placed by manager Alvin Dark, but rather by Orioles reliever Moe Drabowsky, a noted prankster who was trying to disrupt Nash. The prank upset Nash, but proved amusing (and slightly embarrassing) to Krausse and the rest of the Kansas City bullpen.

There were additional hijinks in 1967, but this time, the situation created trouble for Krausse. During a team flight from Boston to Kansas City on Aug. 3, the behavior of several of the A’s upset Finley.

“Things were building to a head on one particular road trip,” said reliever Jack Aker, the A’s’ player representative that season, during a trip to the Hall of Fame years ago. “One of our broadcasters was riding on the plane with us – Monte Moore. Lew Krausse, who was a prankster right from the time he first came up, started ragging on Monte Moore a little bit and some other fellows came in on it. Before we know it, we had an argument on the plane. It was [childish] rowdyism, even though it was nothing that any of the stewardesses on the plane complained about. When the flight was over, they didn’t complain to anyone about it, until Mr. Finley actually asked them. So, it wasn’t a big deal, we didn’t think.

“Then the next day, of course, we have another meeting, where Mr. Finley comes in and starts chewing everybody out. He ended up suspending Lew Krausse.”

On that commercial flight, an eyewitness had claimed to have seen inappropriate behavior by several drunken players, principally Krausse. After hearing about the complaint, Finley had not only suspended Krausse but also fined him $500 and ordered a ban on the serving of alcohol on all team flights. For his part, Krausse said that he did nothing wrong; he and several of the A’s players were merely sitting in the back of the plane, talking and laughing with two of the flight attendants. In retrospect, Krausse believed that Finley was trying to exaggerate the incident so as to give himself another public excuse to move the team out of Kansas City, where the owner was not happy.

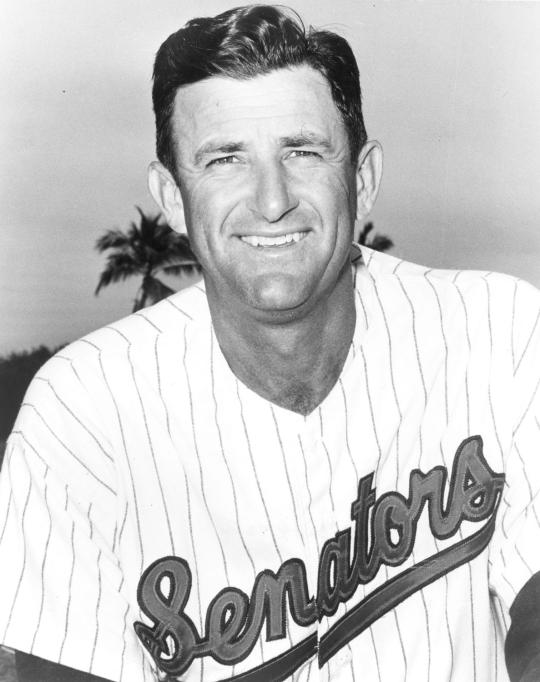

When several players came to Krausse’s defense, saying that he was neither drunk nor disorderly, Alvin Dark supported his players and took up a public stance against Finley. The owner fired the manager shortly thereafter. The incident eventually ended in the release of popular first baseman Ken “Hawk” Harrelson.

Based on the players’ accounts, Krausse had done nothing wrong. Of course, it didn’t help that he was in the midst of a disappointing season. Krause would win only seven of 24 decisions, while seeing his ERA soar to 4.28. Perhaps if Krausse had been pitching better, he might have been spared the wrath of Finley.

Krausse appealed his fine and suspension, but eventually dropped the protest. Still, he remained bitter about the way that Finley had treated him. Both Krausse and Aker demanded that Finley trade them.

For the most part, Finley ignored the request. Krausse himself showed a willingness to forgive and forget. In preparation for the 1968 season, Krausse decided to take a more serious approach to his conditioning. “I worked on the docks in Chester this winter and I want to tell you it was hard work,” Krausse told the Sporting News. “It just made me realize how good a life baseball is… It gave me a different outlook.”

Signing his 1968 contract early, Krausse reported to Spring Training a week before the reporting date.

Known for his love of the night life, Krausse completely changed his off-the-field behavior in 1968. As a younger player, Krausse had earned a reputation for having fun in unconventional ways. “There was the party in Anaheim, the swim-with-your-clothes-on-party,” he told Murray Chass of The New York Times. “We had one or two drinks and then it was off the diving board with our clothes on. We ruined [our] alligator shoes.”

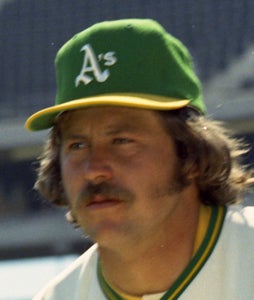

The 1968 season brought another change. Krausse and the rest of the A’s moved to Oakland, where the franchise had relocated from Kansas City. Perhaps energized by the new environment and his improved conditioning, Krausse pitched capably that summer, winning 10 games and helping the A’s to a respectable record of 82-80. For the A’s, it was their first winning season since their days in Philadelphia. Krausse pitched so well that the A’s kept him on their protected list, so that he could not be taken in that winter’s expansion draft.

The next year, Krausse did not fare as well. Reporting to camp late because of his father’s heart attack, Krausse had to adjust to a new role as Oakland’s relief ace. He spent most of the season in the bullpen, but with few save opportunities. That summer turned out to be Krausse’s swansong in Oakland. After the season, trade rumors swirled around Krausse, but November and December came and went without a trade.

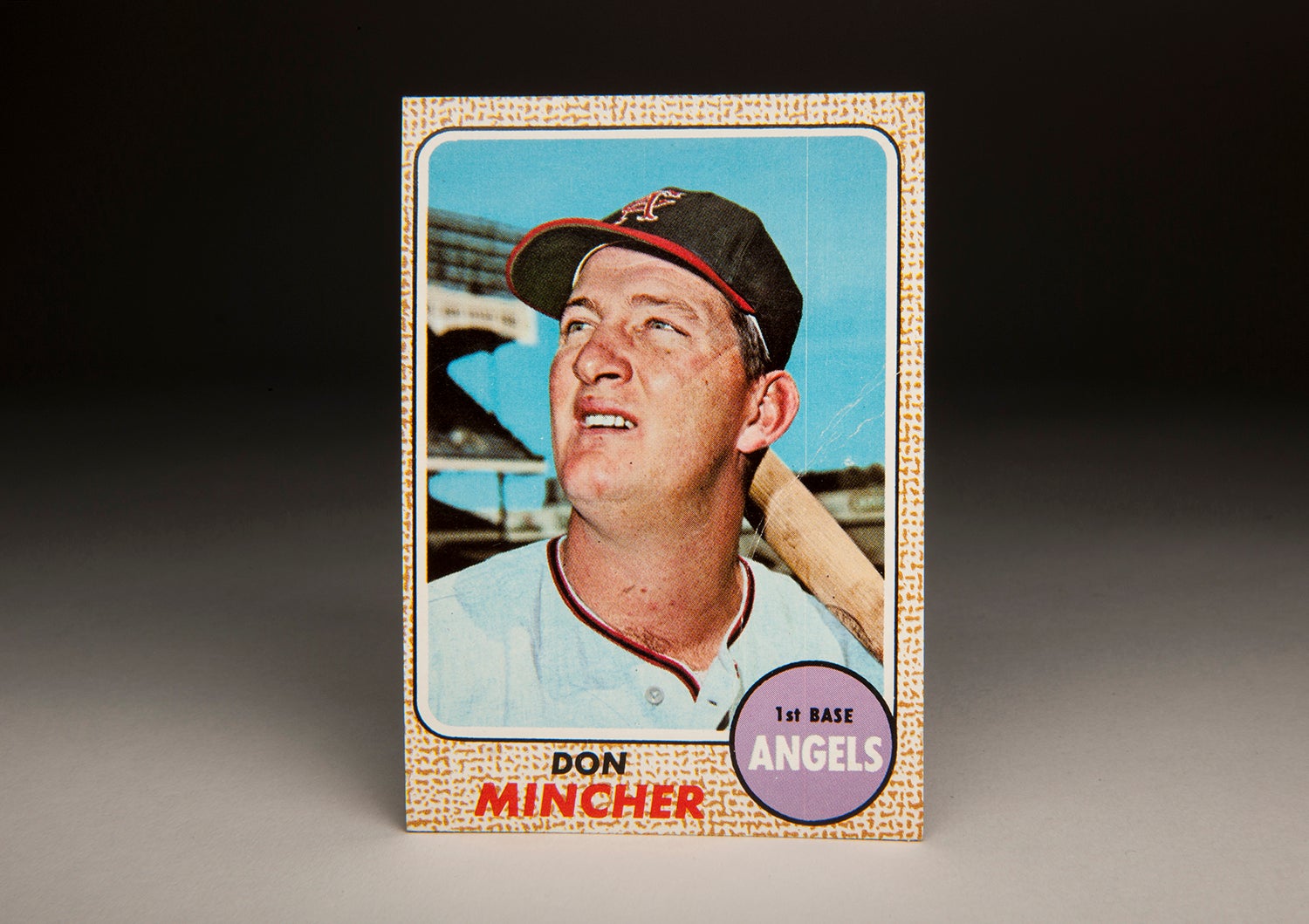

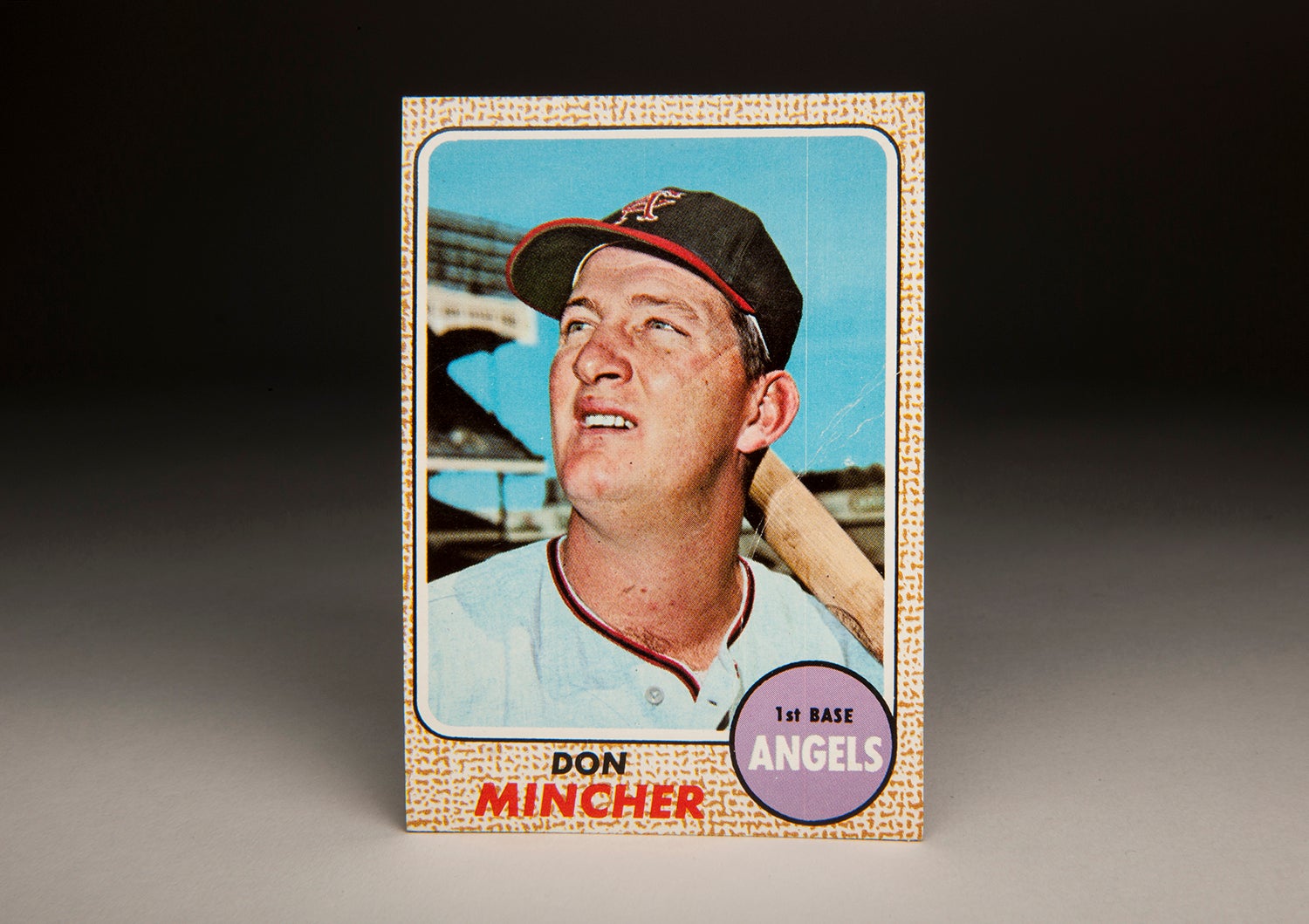

Krausse finally found himself on the move by January. That’s when Finley traded him to the expansion Seattle Pilots in a deal for Don Mincher. In a curiosity, Krausse would never actually pitch for the Pilots, who moved to Milwaukee just before the start of the new season and became the Brewers. The move came at an especially tumultuous time for Krausse, whose wife had recently given birth.

In contrast to his up-and-down career with the A’s, Krausse turned in two good seasons for the Brewers. That didn’t keep him in Milwaukee long-term. He didn’t like pitching in relief, which he did for most of 1971. He also didn’t care for manager Dave Bristol or pitching coach Wes Stock. Given his unhappiness, Krausse asked for a trade. The Brewers accommodated the request, including Krausse in a massive 10-player deal with the Boston Red Sox, one that sent Tommy Harper to Boston for George Scott.

The trade thrilled Krausse, who was now joining an apparent pennant contender after spending all of his career with also-ran teams. The match with Boston seemed ideal, but a labor dispute delayed the start of the new season. As Krausse and his Red Sox teammates worked out on their own at Harvard University, Krausse pitched to backup infielder John Kennedy in a simulated game. The circumstance prompted Krausse and his usual sense of humor.

“No matter what comes out of this strike,” Krausse told the Sporting News, at least I can tell my grandchildren that I pitched to John Kennedy at Harvard.”

Once the season started, Krausse retained his humor but lost control of his fastball. He made only 24 appearances for the Red Sox, mostly out of the bullpen, and put up a bloated ERA of 6.38. The Red Sox brought him back for Spring Training in 1973, but released him before Opening Day.

From there Krausse signed with the A’s, who immediately assigned him to Triple-A, where he spent the entire season. On Sept. 1, the A’s sold his contract to the St. Louis Cardinals, but he made only one appearance for the Redbirds, who released him in October. From there, he staged a comeback with the Atlanta Braves, where he introduced a sidewinding motion to his repertoire. He pitched decently with Atlanta, but was released after the season. He tried to stage another comeback with the A’s in 1975, but failed to make the Opening Day roster. In midseason, Krausse retired at the early age of 31.

During his playing career, Krausse became friends with other Pennsylvania legends like Danny Murtaugh and Mickey Vernon, whom he worked with during wintertime business ventures. One of those ventures included a men’s clothing store. Admittedly, Krausse, Vernon, and didn’t know much about the finer points of men’s clothing, but they did their best as salesmen, in between playing practical jokes on one another – much to the “amusement” of their boss.

Rather than go into the clothing business fulltime in Pennsylvania, Krausse decided to move to Kansas to start his own company, one that specialized in manufacturing aluminum and stainless steel. Krausse enjoyed tremendous success, more than he had during his star-crossed time in baseball, allowing him to retire comfortably and turn the business over to his son. As Krausse told author Chris Zantow in 2016, “We never made enough money playing. I entered into the business world and made millions!”

Playing golf regularly as part of his retirement, Krausse remains a legendary figure in his native Delaware County in Pennsylvania. The days of jumping off the diving board fully clothed, or feuding with a difficult owner, are long gone now, even if it’s fun to reminisce about those episodes. It’s certainly been an eventful life for the guy with the colorful rookie Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

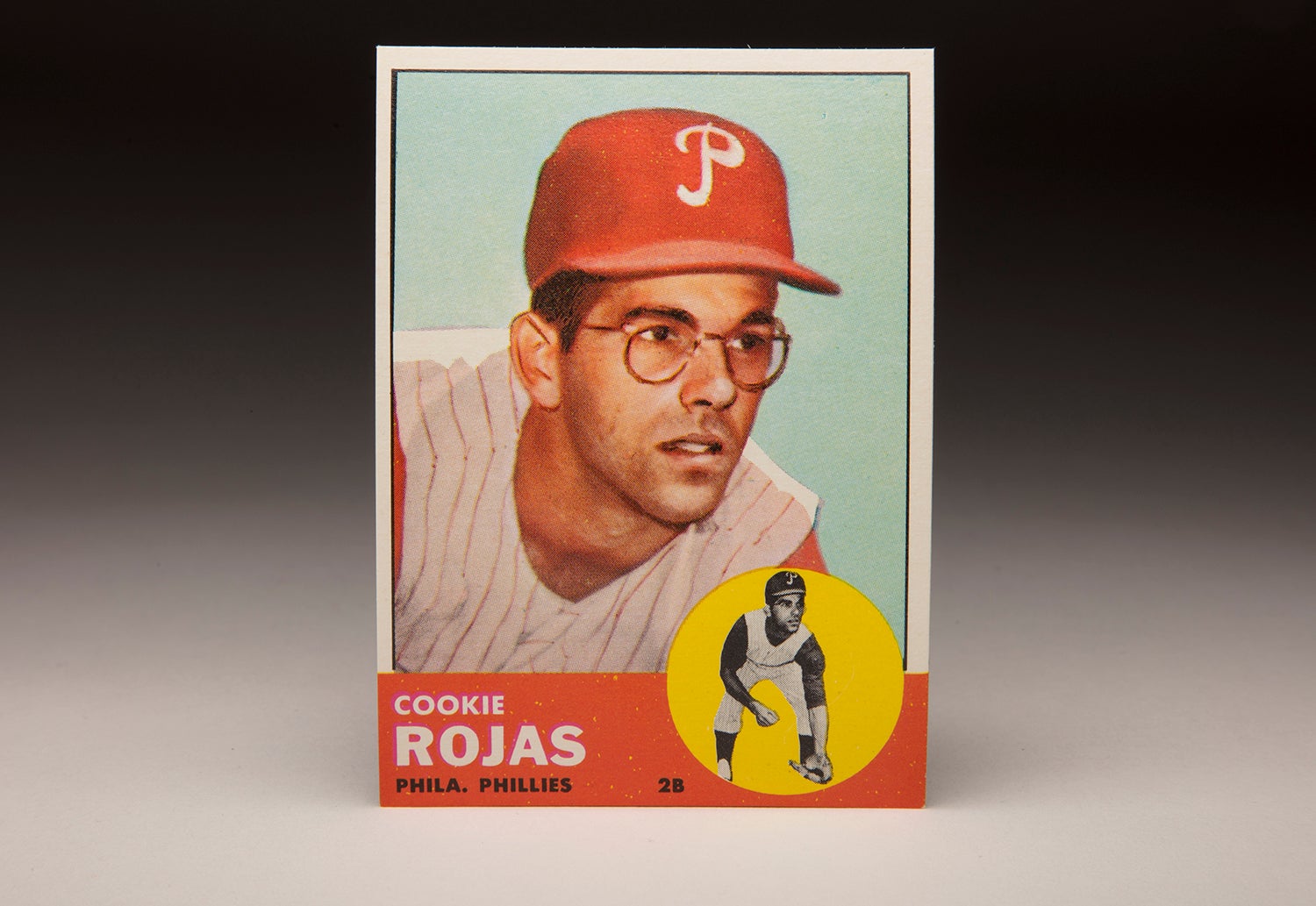

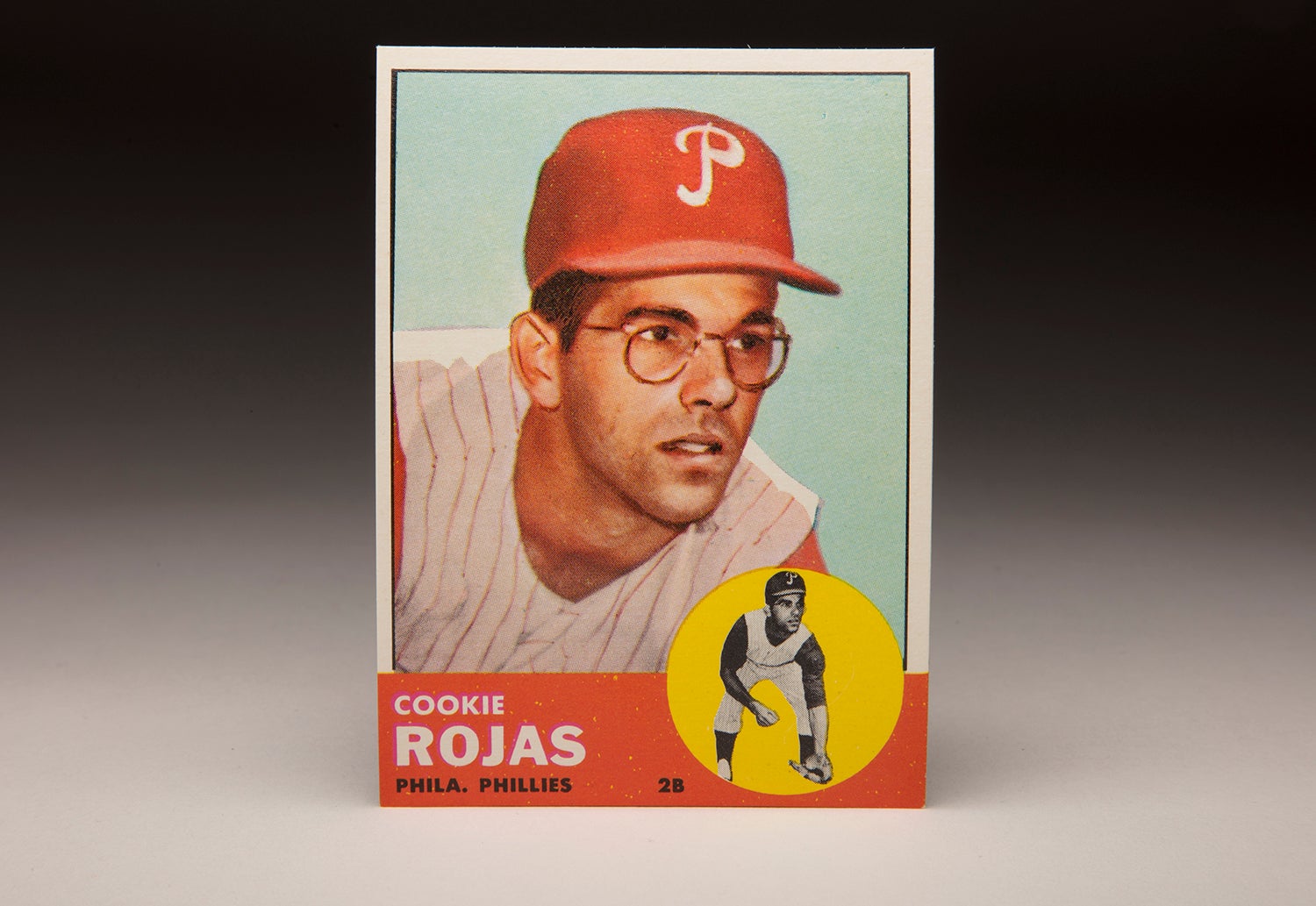

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

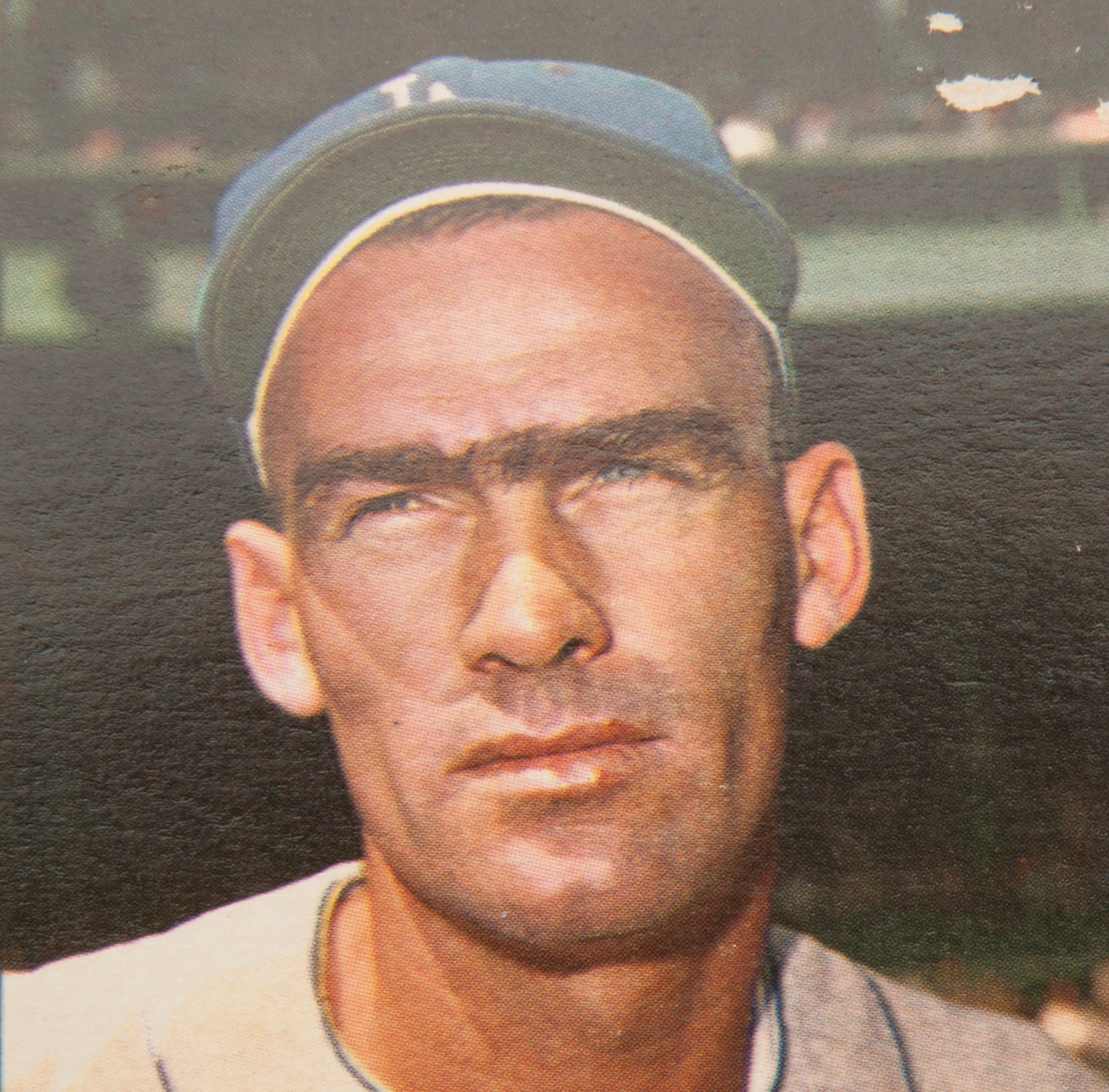

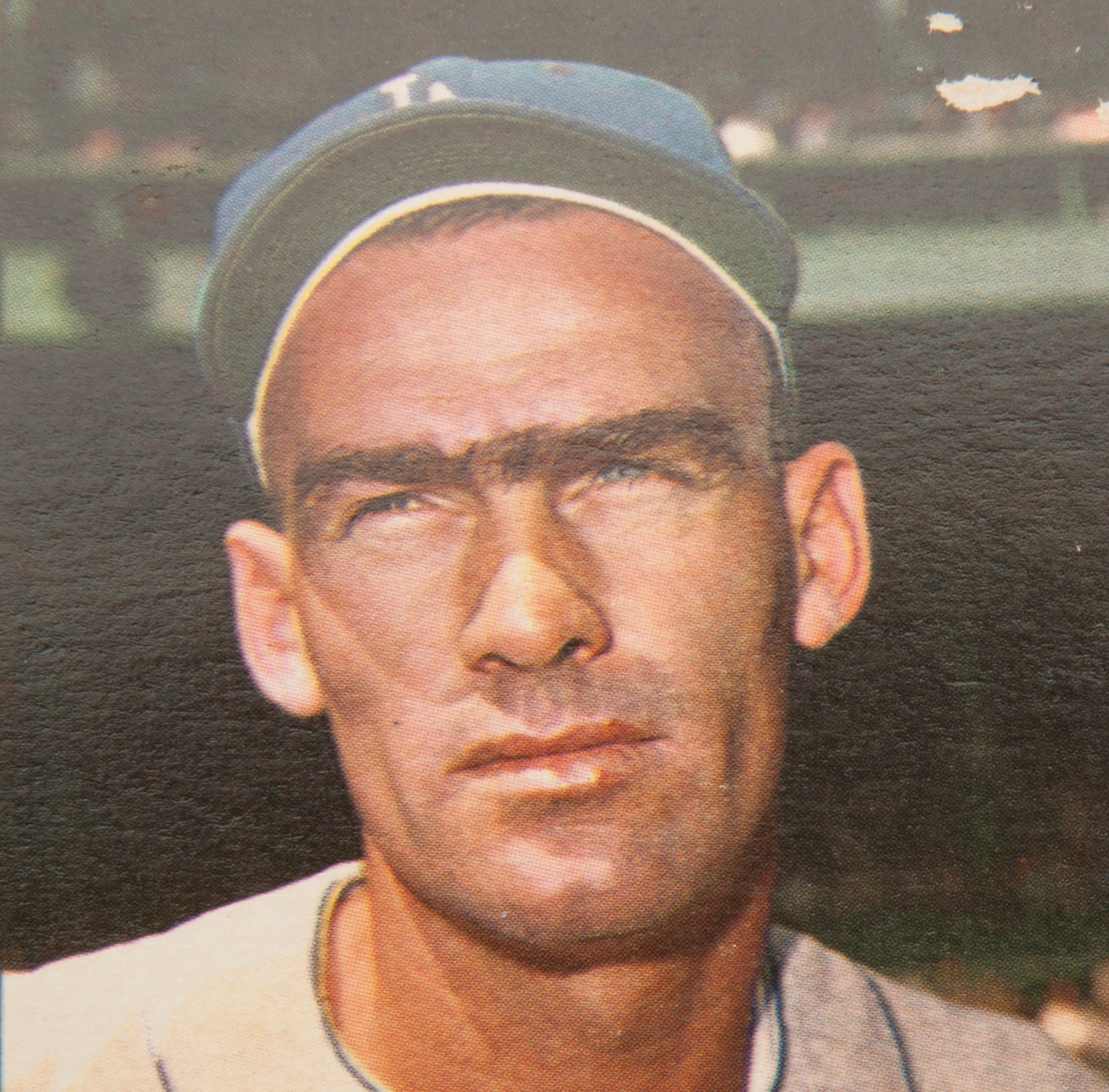

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

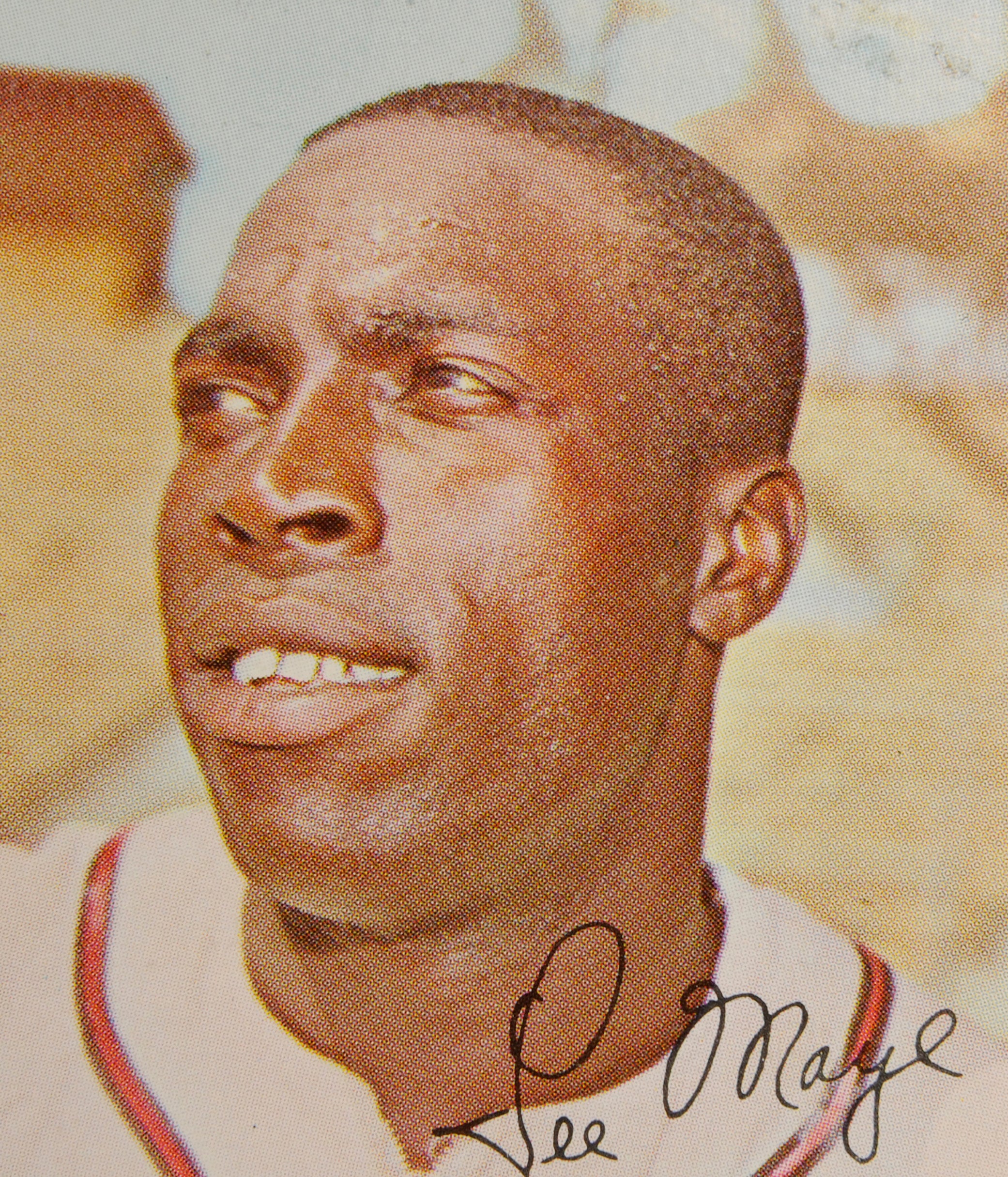

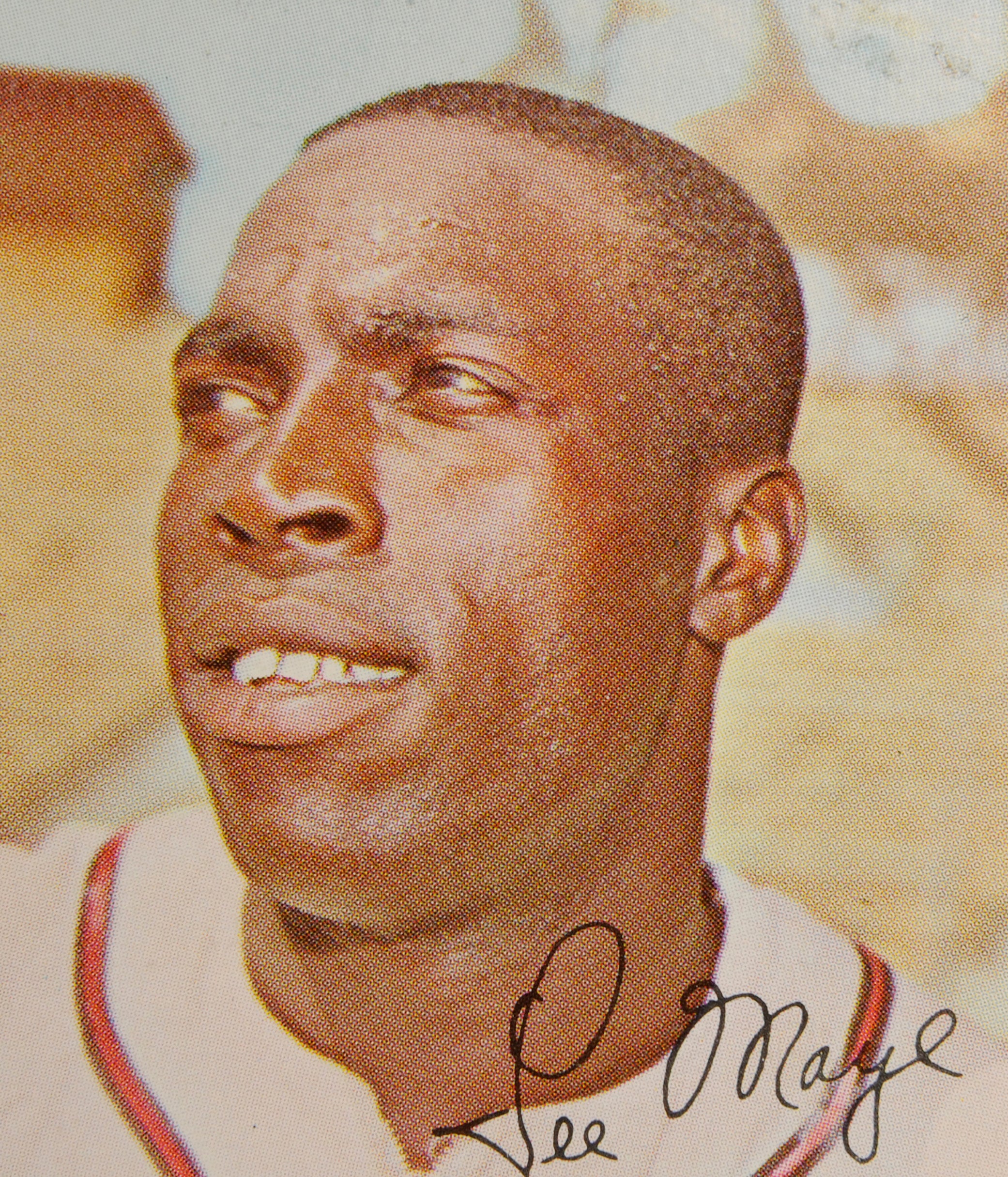

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Don Mincher

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Cookie Rojas

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye