There are a lot of things I can remember and be proud of. I didn’t make too many enemies. I didn’t disgrace myself, and I played the game as hard as I could. I can walk out with a clean slate and a clean mind.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Don Mincher

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Don Mincher

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

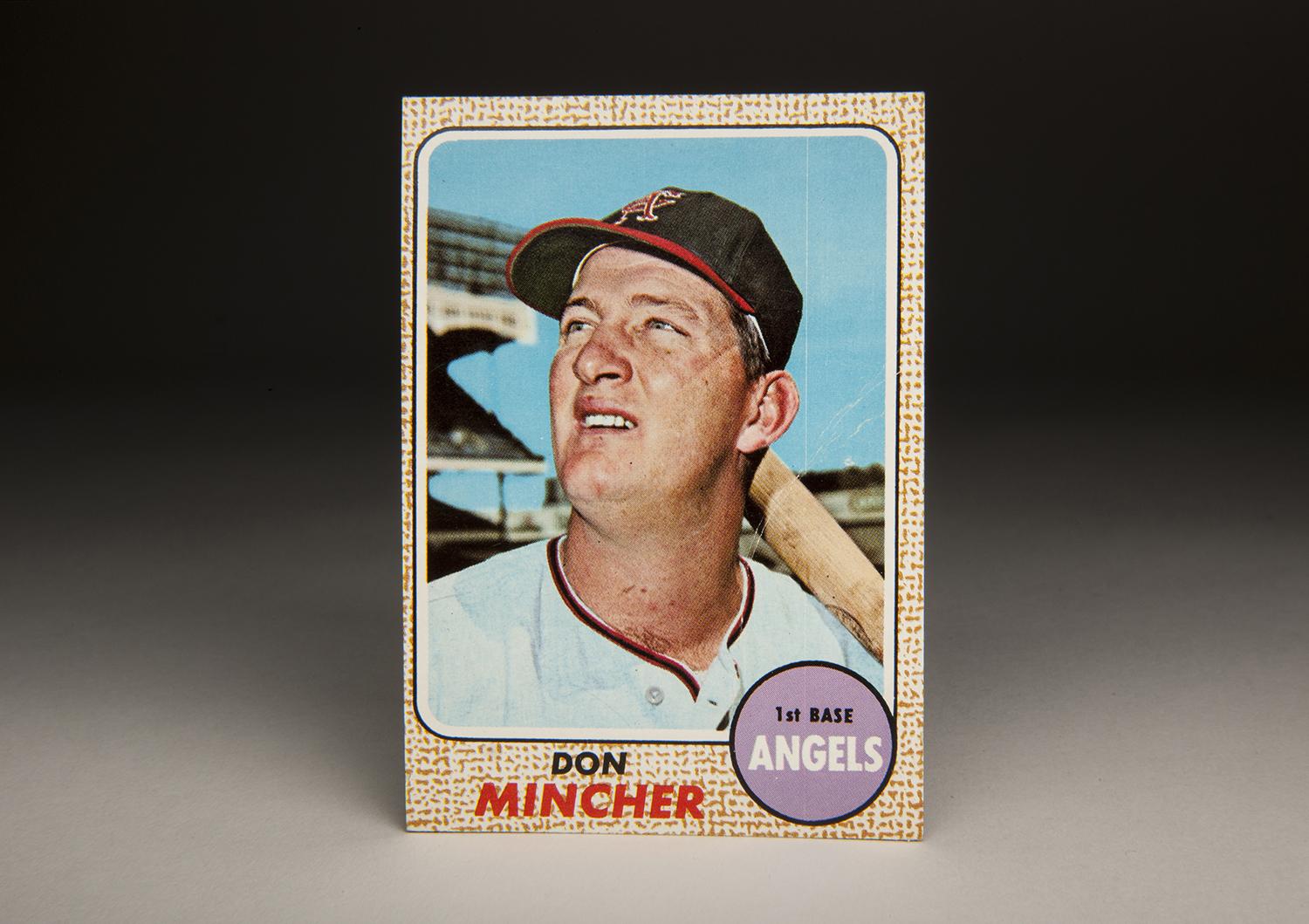

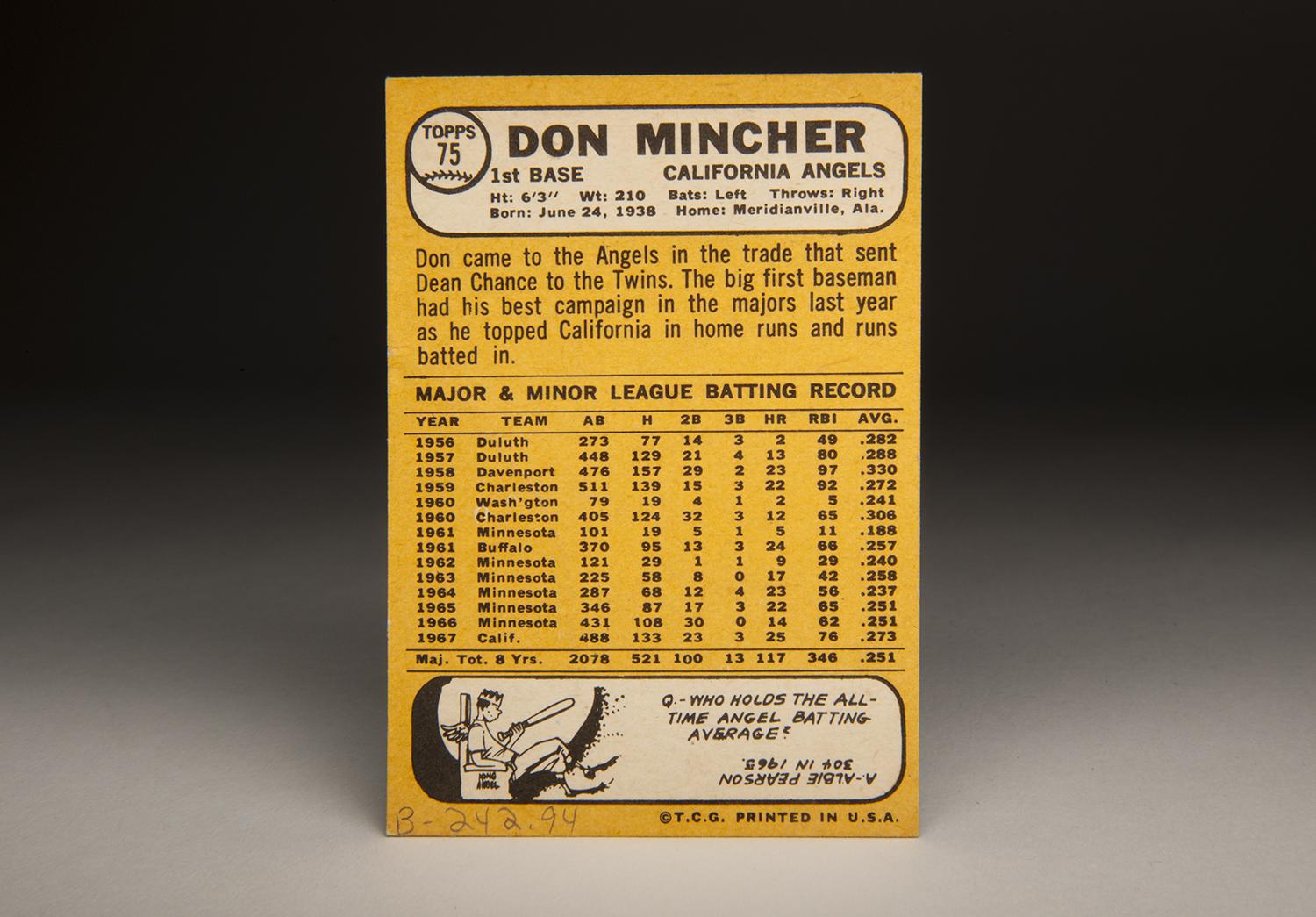

The 1968 Topps card of Don Mincher has all the elements of a classic baseball card: A strapping slugger holding a bat on his left shoulder, dramatically looking to his right as the photographer takes his picture. (Notice how Mincher’s top button is left unbuttoned; that’s how the home run hitters wear their jerseys.)

Then there is the backdrop of the Yankee Stadium façade, often seen in the backgrounds of cards from the 60s and 70s, a ballpark feature that epitomizes what we remember about the “house that Ruth built.” To top it off, the brilliant blue sky lightens the card, giving us a reminder of what it was like to spend an afternoon at the Stadium.

In some ways, Don Mincher was a classic 1960s ballplayer. Not a Hall of Famer and rarely a star, he was nonetheless a very good player for some very fine teams, including a couple of great ones. Over the years, I’ve heard some broadcasters refer to a certain type of player as “a good, old-fashioned country ballplayer.” Mincher was just that kind of player.

From a personal standpoint, Mincher will always hold a particularly important place. That’s because Don Mincher was the first player I interviewed for the first book I ever wrote, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s. Not only was Mincher the first player to grant me some time on the telephone – this was back around 1995 or 1996 – but he might just have been the best of the interviews I did. That’s not because of anything I did. Keep in mind that I really didn’t know what I was doing; I had done interviews before, but never for a full-length book, and this was a book for which I had not yet developed a theme. On this subject, I was as green as the Oakland A’s uniforms of the early 1970s.

Don made the interview worthwhile, and easy, all on his own. He spoke freely about the inner workings of the A’s teams during the early years of their dynasty, back in 1971 and ’72, when he was finishing his career. He told me about the strong personalities on the A’s who sometimes argued, sometimes fought. He gave me advice on whom I should interview next, and which ones I might be better off avoiding. He even warned me that one player might ask me for money, which would have made the project especially difficult since I had no money to spend!

During our long talk on the phone, Mincher treated me like an old friend. He made me feel as if it wasn’t bothering him. If anything, this was an interview that he was eager to do. He seemed grateful that somebody was taking an interest in his career and life in baseball, especially since it had been more than 20 years since his retirement as a player.

Not one to brag about himself, Mincher was modest about his playing days, preferring to talk more about his teammates. In actuality, Mincher was better than he was willing to let on. A left-handed hitter with enormous strength, he earned the nickname of “The Mule.” He hit with power, hitting exactly 200 home runs over his career, and exhibited discipline at the plate, walking nearly as often as he struck out. Even though much of his career coincided with the dead ball era of 1960s baseball, Mincher managed to post OPS numbers of better than .800 a half-dozen times.

Mincher didn’t just put up good numbers for bad teams, either. He played for two exceptional clubs, the 1965 pennant-winning Minnesota Twins and the world championship A’s of 1972. He was the starting first baseman for the former team, and a key backup for the latter. In the 1972 World Series, he helped the A’s win Game 4 with a pinch-hit RBI single, which turned out to be the final at-bat of his career.

Mincher’s major league days began back in 1960, when he debuted for the old Washington Senators. There wasn’t much playing time available, not with Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew ahead of him on the first base depth chart, but Mincher would eventually find his niche. In 1961, Mincher and the rest of the Senators moved to the Twin Cities, reborn as the Minnesota Twins’ franchise.

Over his first two seasons in Minnesota, Mincher remained a bench player, but received a break in 1963, when the Twins moved Killebrew to the outfield. That opened up some playing time for Mincher in a time-sharing arrangement with Vic Power at first base. In the spring of 1965, Mincher asked for a trade to a team that could offer him more playing time, but he remained put in Minnesota. That season, his playing time increased, as he became the primary first baseman for the pennant-winning Twins. Mincher hit 22 home runs and slugged .509, adding depth to a lineup that already featured Killebrew, Tony Oliva, and Bob Allison.

In that fall’s World Series, Mincher started all seven games against the vaunted Los Angeles Dodgers. He didn’t hit much, his average falling to .130, but did blast a home run against Hall of Famer Don Drysdale in Game 1, helping the Twins to a victory. Ultimately, the Twins would lose a tough Series to the Dodgers in seven games.

With Killebrew slated to return to first base, Mincher became expendable after the 1966 season. The Twins traded him to the California Angels as part of a package for onetime Cy Young Award winner Dean Chance. While Mincher loved playing in Minnesota, he took well to Southern California. He hit 25 home runs, drew 69 walks, and earned selection to his first All-Star Game. After the season, baseball writers showed him some support in the American League MVP voting.

Then came the near tragedy of 1968. In only the second game of the season, Mincher stepped in against intimidating left-hander Sam McDowell, arguably the hardest throwing southpaw in the league. McDowell unleashed a fastball that rode in on Mincher, smashing him in the cheekbone. Always tough, Mincher missed only nine games, but a series headaches and recurrent dizziness bothered him for the rest of the season.

Concerned that Mincher was now damaged goods, the Angels left him unprotected in the expansion draft. The Seattle Pilots jumped on the chance to acquire a left-handed slugger of Mincher’s reputation. Installed as the everyday first baseman in Seattle, Mincher played well for the Pilots, earning selection to his second All-Star team.

After the 1969 season, the Pilots moved to Milwaukee to become the Brewers. But Mincher never made the shift with the franchise. Before the move to Milwaukee, the Pilots traded Mincher to the A’s in a deal for four lesser players. Mincher continued to hit well, giving Oakland solid production from a first base position that had been lacking in power.

After the 1971 season, Mincher endured yet another franchise shift, as the Senators moved to Arlington, TX, where they became known as the Rangers. Through all of the shifts and all of the trades, Mincher retained the even-keeled disposition that made him so popular with teammates. Quiet and reserved but ever the leader, Mincher established a reputation as an elder and respected statesman in the Rangers’ clubhouse. “If you didn’t like Don Mincher,” says Jimmy Driscoll, at the time a young infielder with the Rangers, “you didn’t like yourself.”

Mincher’s teammates so admired him that they elected him as the team’s player representative. Rangers owner Bob Short, running contrary to his players, became upset with Mincher for failing to reveal information from the union side that led to a strike at the beginning of the 1972 season. That summer, Short exacted some payback, trading Mincher back to Oakland, where he assumed a role as a pinch-hitter and backup first baseman to Mike Epstein.

The trade turned out to be a huge favor for Mincher, who was departing a last-place team for a team headed straight to the World Series. In the ninth inning of Game 4, with runners on first and second, one out, and the A’s trailing by a run, manager Dick Williams called on Mincher as a pinch-hitter. The stately veteran promptly lined a single into right-center field, tying the game and setting the stage for a dramatic comeback victory. Mincher’s at-bat, the final appearance of his major league career, helped the A’s win the title, while also earning Mincher his first World Series ring.

No longer wanting to be a bench player and bothered by bad pain in his shoulder, Mincher decided to retire after the Series. Charlie Finley, Oakland’s enterprising owner, later approached Mincher to tell him about the new designated hitter rule that had been signed into law. He offered Mincher a chance to come back as Oakland’s first DH. He would have made an ideal DH, platooning against right-handed pitching. Mincher thought about the offer, but the pain in his shoulder was so bad that it became difficult even to comb his hair. All things considered, Mincher decided that retirement was the better option.

In making the decision, Mincher felt no bitterness about the end of his career. “There are a lot of things I can remember and be proud of,” Mincher told Ron Bergman of the Sporting News. “I didn’t make too many enemies. I didn’t disgrace myself, and I played the game as hard as I could. I can walk out with a clean slate and a clean mind.”

Unlike some ballplayers who struggle to find life after baseball, Mincher made a smooth transition to the front office. He went back home to Huntsville, Ala., where he ran the Double-A Huntsville Stars of the Southern League for 15 years as a general manager and part owner. Having established a terrific reputation within the minor league world, he agreed to become the Southern League’s interim president before accepting the job on a fulltime basis.

In all of his minor league jobs, Mincher made a strong impression on fellow workers, the media, and fans with his easygoing manner, his intelligence, his willingness to work and his basic integrity. In his hometown of Huntsville, Mincher became a legendary figure.

In 2012, one year after Mincher retired as Southern League president, Huntsville mourned its good citizen. That March, Mincher died after a battle with heart disease and pneumonia. He was 73 years old.

I never met Mincher face-to-face, but I felt like I had during our long and meaningful phone conversation. Some people struggle to talk on the phone, but not Mincher. He was so vibrant, so friendly, that it seemed like he was in the room with me.

I talked to Don Mincher just that one time, but his words stayed with me, both in my book and in my thoughts today. I miss having the chance to talk to him again. For those who really knew him well, those good people in Huntsville, I can only imagine how much they have missed him since his passing in 2012.

Guys like Don Mincher make you proud to be a baseball fan.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

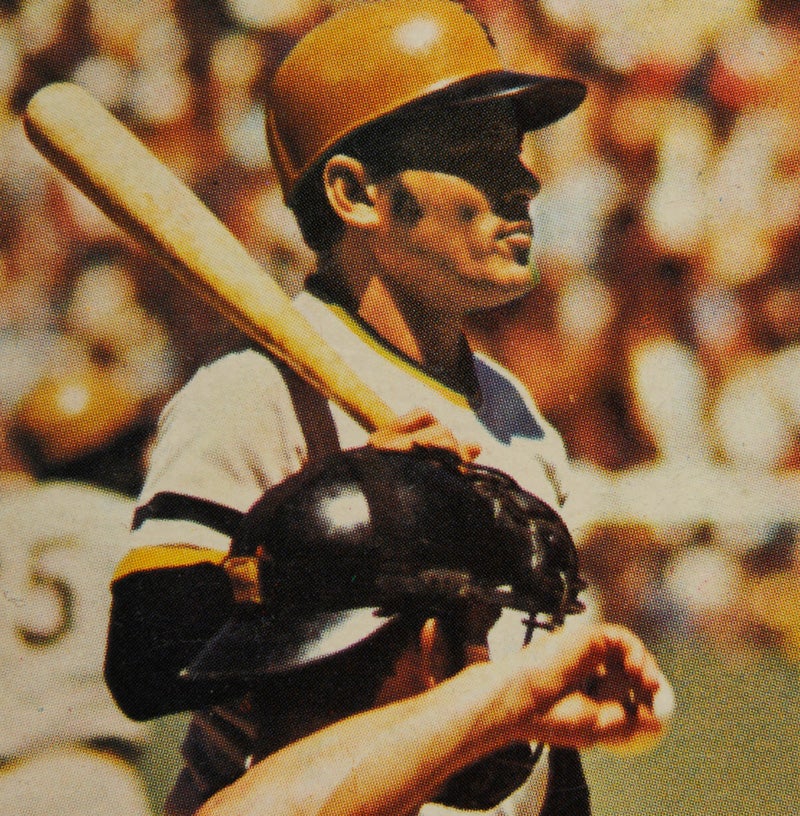

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

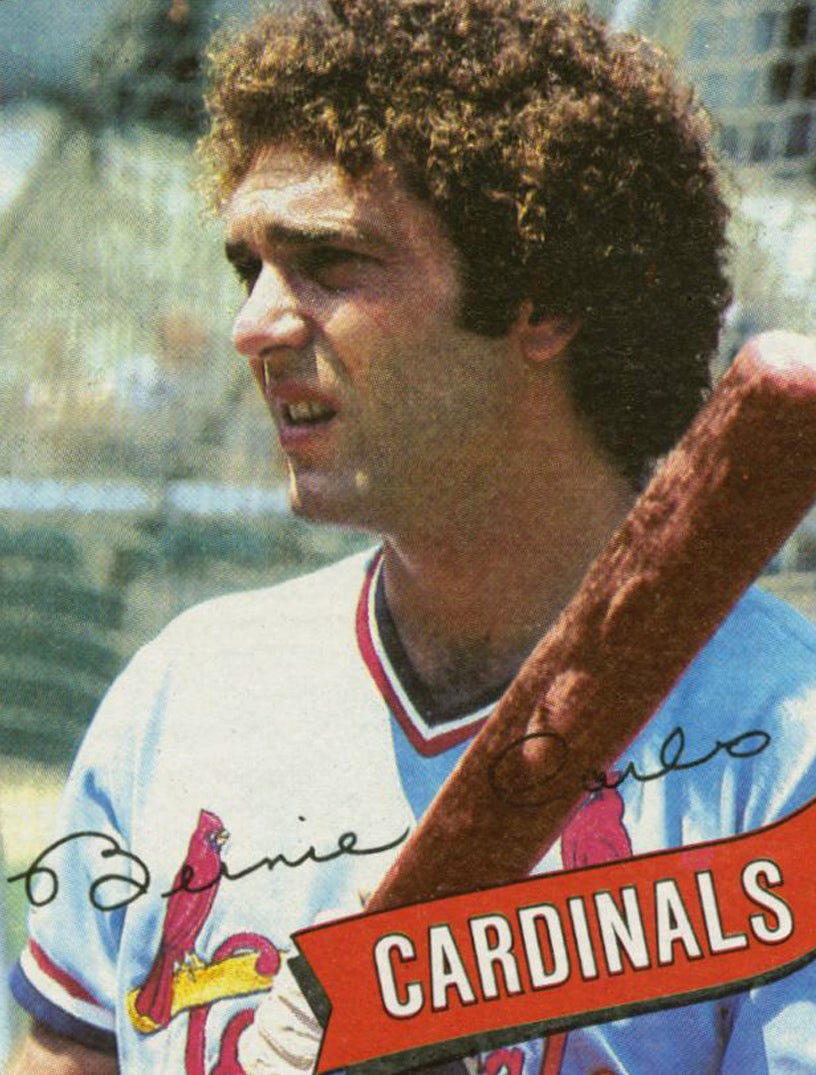

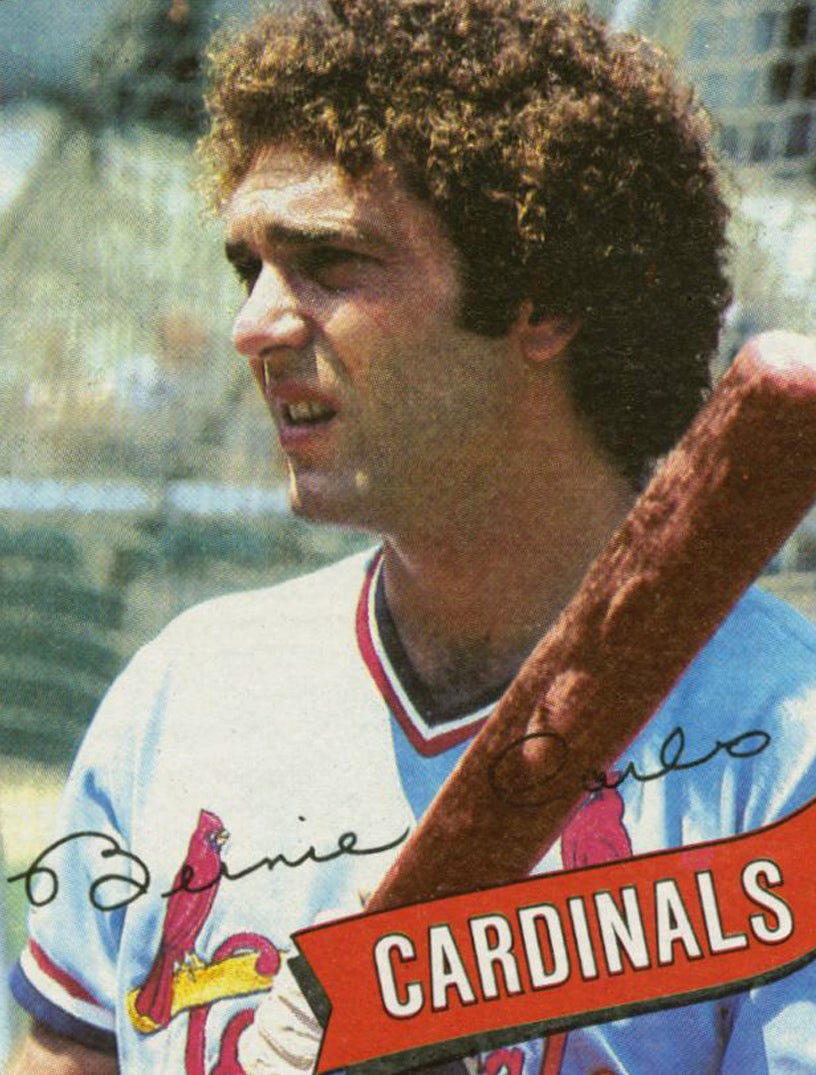

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

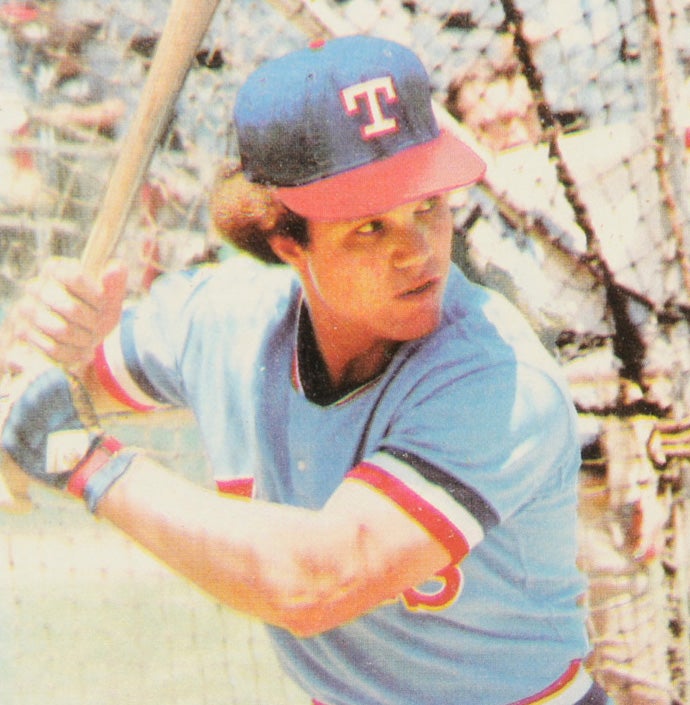

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler