- Home

- Our Stories

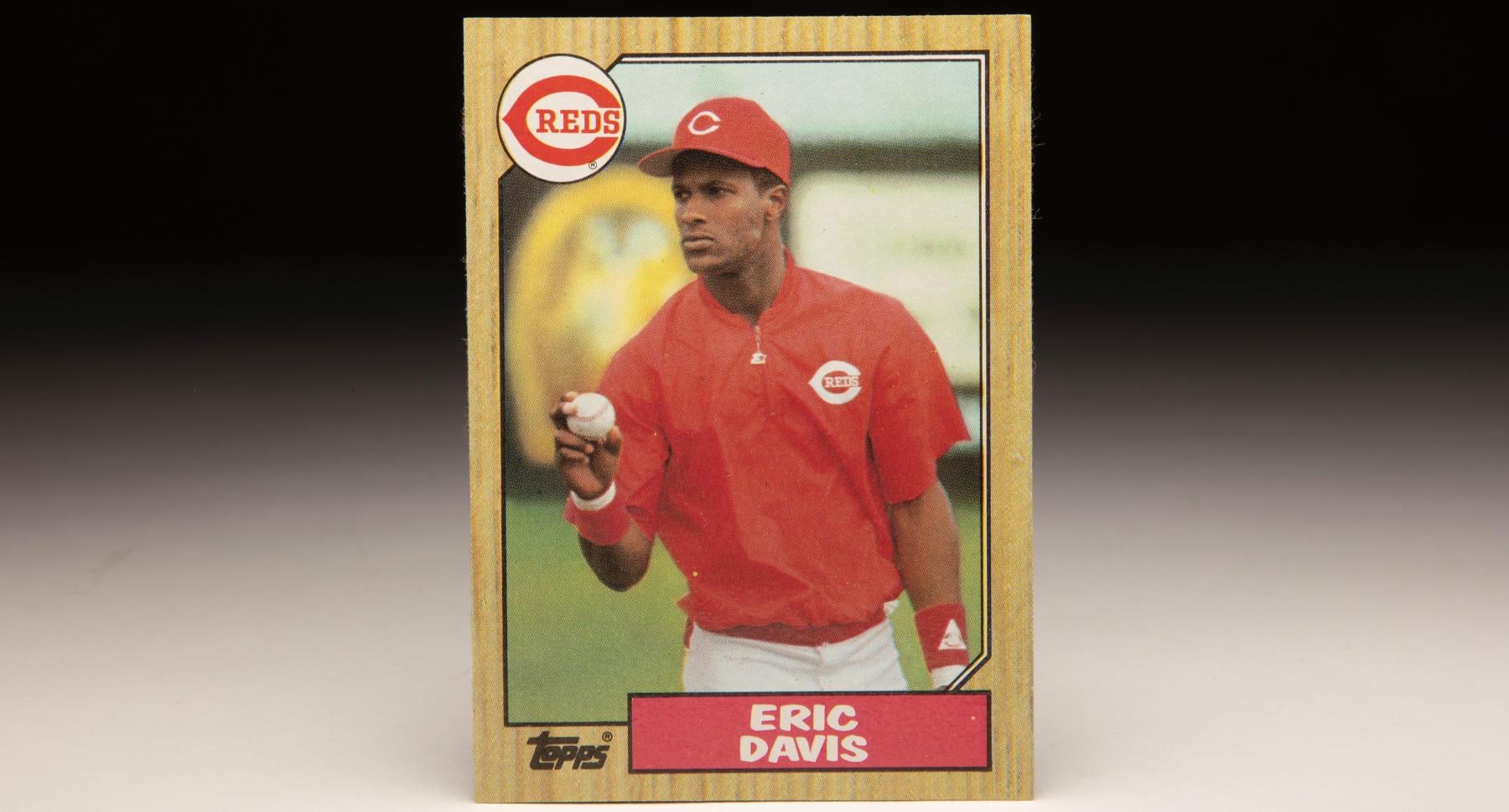

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Eric Davis

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Eric Davis

Eric Davis had suffered through an injury-filled 1991 campaign, sidelined in June by a bad hamstring and then for a month in late summer by chronic fatigue.

But while standing around the batting cage on a hot August day at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium, Davis was cajoled by teammates into taking some swings with a composite ceramic/graphite bat made by Easton.

The resulting line drives down the right-field line – the right-handed Davis’ non-pull side – left visible marks on the cement retaining wall.

“Man, the ball jumps from this,” Davis told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “You’d have to move the fences back, and someone would still get hurt.”

Davis had experience with both. Because when healthy and swinging his customary lumber, Davis was as dangerous as any hitter of the 1980s.

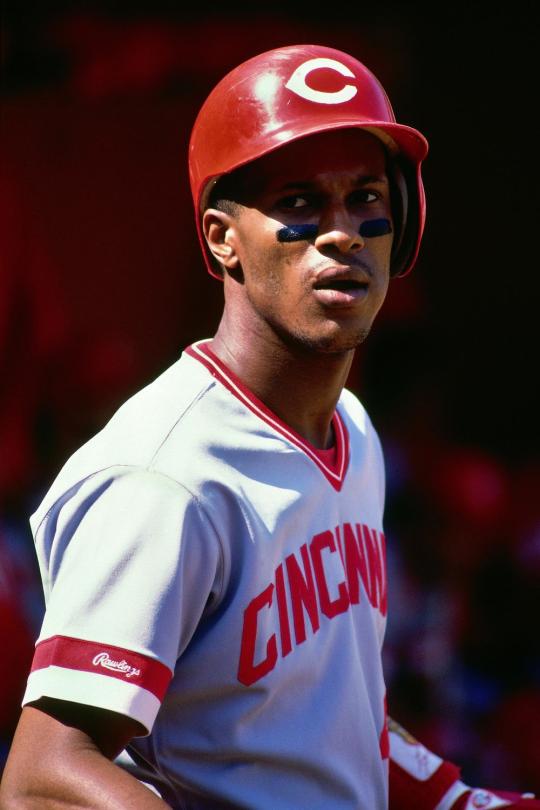

Eric Keith Davis was born May 29, 1962, in Los Angeles and grew up in the impoverished area of South Central L.A. His first love was basketball, but Davis soon discovered that his wiry 6-foot-2 frame was better suited for the diamond.

Teammates with future big leaguers Darryl Strawberry and Chris Brown on the Compton Moose Pony League team and a Fremont High School teammate of future NFL star David Fulcher, Davis turned down several offers to play his high school ball at neighboring schools – opting to stay where he grew up.

“We used to slide on the cement,” Davis told the Cincinnati Post of his days playing on a lot near the 68th Avenue Elementary School. “There would be times we’d come down here with all three balls: Basketball, football and baseball. We’d play a little bit of one then switch to something else.”

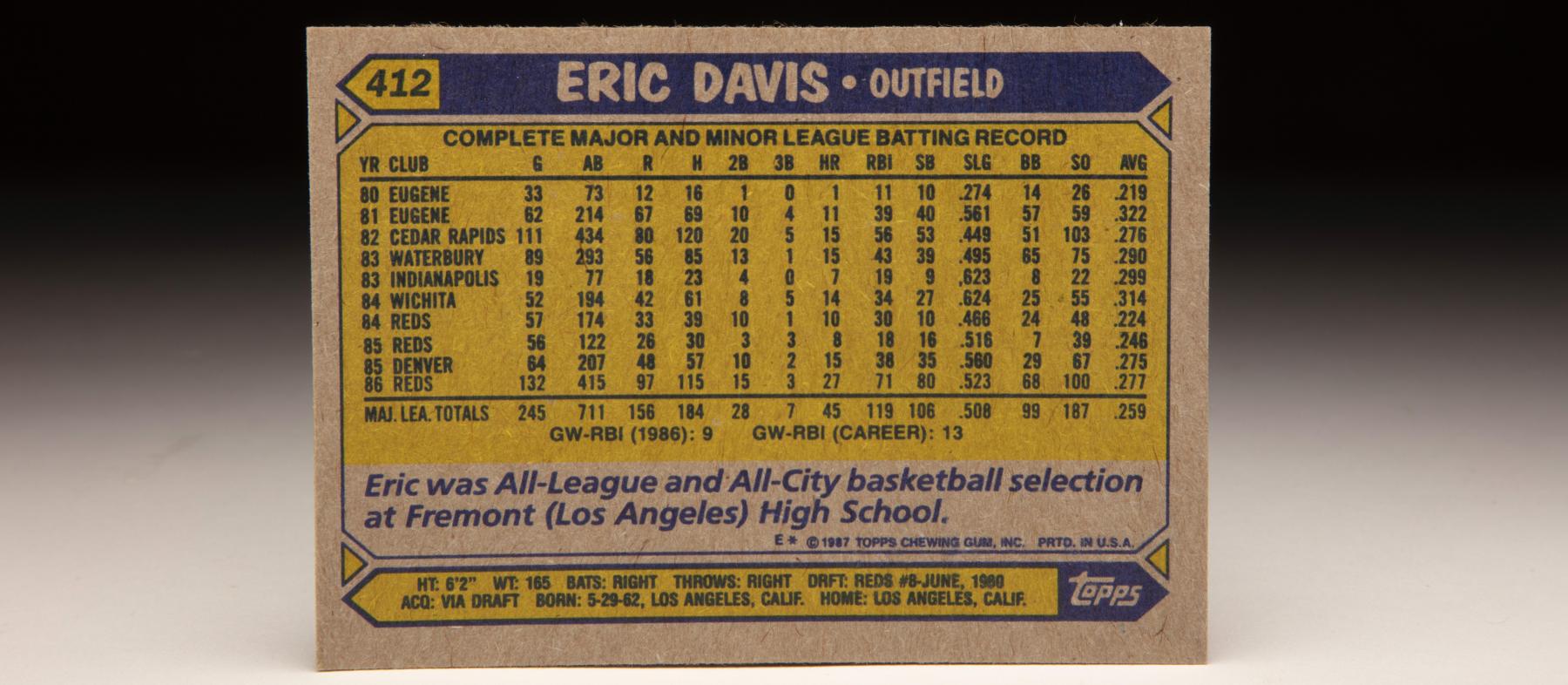

Fremont High School produced several future big leaguers, including Gene Mauch, Bob Watson, Bobby Tolan, Willie Crawford, George Hendrick, Chet Lemon and Dan Ford. But Davis, who hit .667 with 50 stolen bases as a senior, went unselected until the Reds tabbed him in the eighth round of the 1980 MLB Draft.

“I could have played (college basketball) anywhere in the country,” said Davis, who by his own account was recruited by at least 50 schools.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

But Davis believed that baseball was his best shot at stardom and signed with the Reds. He was sent to Class A Eugene of the Northwest League that summer, where he hit .219 with 10 stolen bases in 33 games. Davis returned to Eugene in 1981, this time hitting .322 with 40 steals and 67 runs scored in 62 games.

In 1982, Davis – now an outfielder after playing shortstop as an amateur – flashed his all-around game over a full season at Class A Cedar Rapids of the Midwest League, hitting .277 with 15 homers, 56 RBI, 80 runs scored and 53 steals in 111 games. He began the 1983 season at Double-A Waterbury, hitting .290 with 39 steals in 89 games before earning a promotion to Triple-A Indianapolis.

The Reds brought Davis to Spring Training in 1984, but Reds manager Vern Rapp made it clear that Davis was unlikely to go north with the team despite impressing teammates and opponents in Spring Training games.

“If I have to go to Triple-A, I’ll go and I’ll work hard there,” Davis told the Tampa Tribune after drawing comparisons to former Reds slugger George Foster following a two-homer game against the White Sox on March 15. “I figure if I do go back, I’ll just be polishing my skills.”

Davis did return to Triple-A, this time in Wichita, where he was hitting .311 with 10 homers, 25 RBI and 10 steals through mid-May when the Reds brought him to the big leagues.

“Our plans are to use him for defensive replacement when needed,” Rapp told the Dayton Daily News. “I felt this spring he was the best defensive outfielder we had. We also felt he needed further minor league seasoning.”

Rapp was true to his word, using Davis as a pinch-hitter in his big league debut May 19 and then playing him only sporadically for the next two weeks. When outfielder Duane Walker returned from the disabled list on June 4, Davis was sent back to Wichita. But he continued to wear out Triple-A pitching – and the Reds brought Davis back to Cincinnati in late June.

This time, Rapp put Davis in center field and kept him there. He struggled for the next month and a half, hitting .198 with three homers and seven steals in 29 games. Then on Aug. 15, the Reds fired Rapp – who had an often-tense relationship with his players – and brought in Pete Rose as player/manager.

At the same time, Davis went on the disabled list with a right knee injury – the result of Osgood-Schlatter disease. He returned in September but missed more time due to the ailment and had the knee surgically repaired in the offseason. He finished the year with a .224 batting average, 10 homers, 30 RBI, 33 runs scored and 10 steals in 57 games with the Reds.

Davis began the 1985 season as one of baseball’s most touted young players and was in the Opening Day lineup as the Reds’ center fielder, going 1-for-3 with a double, two runs scored and two stolen bases out of the leadoff spot. But he struggled to make contact more often than not – something that Rose did not appreciate.

Davis fanned at least once in 15 of his 17 games in April, finishing the month batting .152 with three homers, six steals and 25 strikeouts.

“He’s pulling away and swinging up,” Reds hitting coach Billy DeMars told Scripps Howard News Service about Davis’ struggles. “I’d just like him to know that I’m here to help him.”

But even at that early point in his career, Davis fully believed in his athletic ability.

“I trust my own judgment,” Davis said. “If I’ve gotten this far, I know a little something about hitting.”

Rose removed Davis from the starting lineup for much of May, but the change did not help. Following the Reds’ game on June 4, the team sent Davis – hitting .189 – back to Triple-A.

“He can steal bases and he can hit the ball 500 feet,” Rose told the Associated Press. “He’s got to put the ball in play and not strike out. If he does the things I think he can do down there, he’s going to be a star here for many years. It’s not like I traded him somewhere.”

In 64 games with Triple-A Denver, Davis hit .277 with 15 homers, 38 RBI and 35 steals. When he returned in September, Rose slowly worked him back into the lineup – and Davis finished the season with nine hits, including three home runs, in his final 19 at-bats, wrapping up his year with a .246 average, eight homers and 16 steals in 56 games with the Reds.

In 1986, Davis was once again the Reds’ Opening Day center fielder. Once again he struggled, lugging a .200 batting average and .298 on-base percentage into June.

But on June 14, Davis single-handedly helped Cincinnati beat the Braves when – with the game tied at 1 – he singled to left to lead off the ninth, went to second on a bunt by Buddy Bell, stole third and scored when the ball got away from Atlanta third baseman Rafael Ramírez.

Davis went 2-for-4 with a home run and three RBI the next day and finished the season’s final 93 games on an incredible tear, hitting .297 with 23 homers, 78 runs scored, 59 RBI, 63 steals and a .398 on-base percentage.

For the season, Davis totaled 27 homers and 80 steals – becoming the second member of the 20 homer/80 steal club, joining Rickey Henderson, who turned the trick in 1985 and 1986. No player has reached those numbers since.

“He’s got phenomenal ability and world-class speed,” Reds teammate Dave Parker told the Los Angeles Times about Davis in 1986. “He’s going to stand this league on its head.”

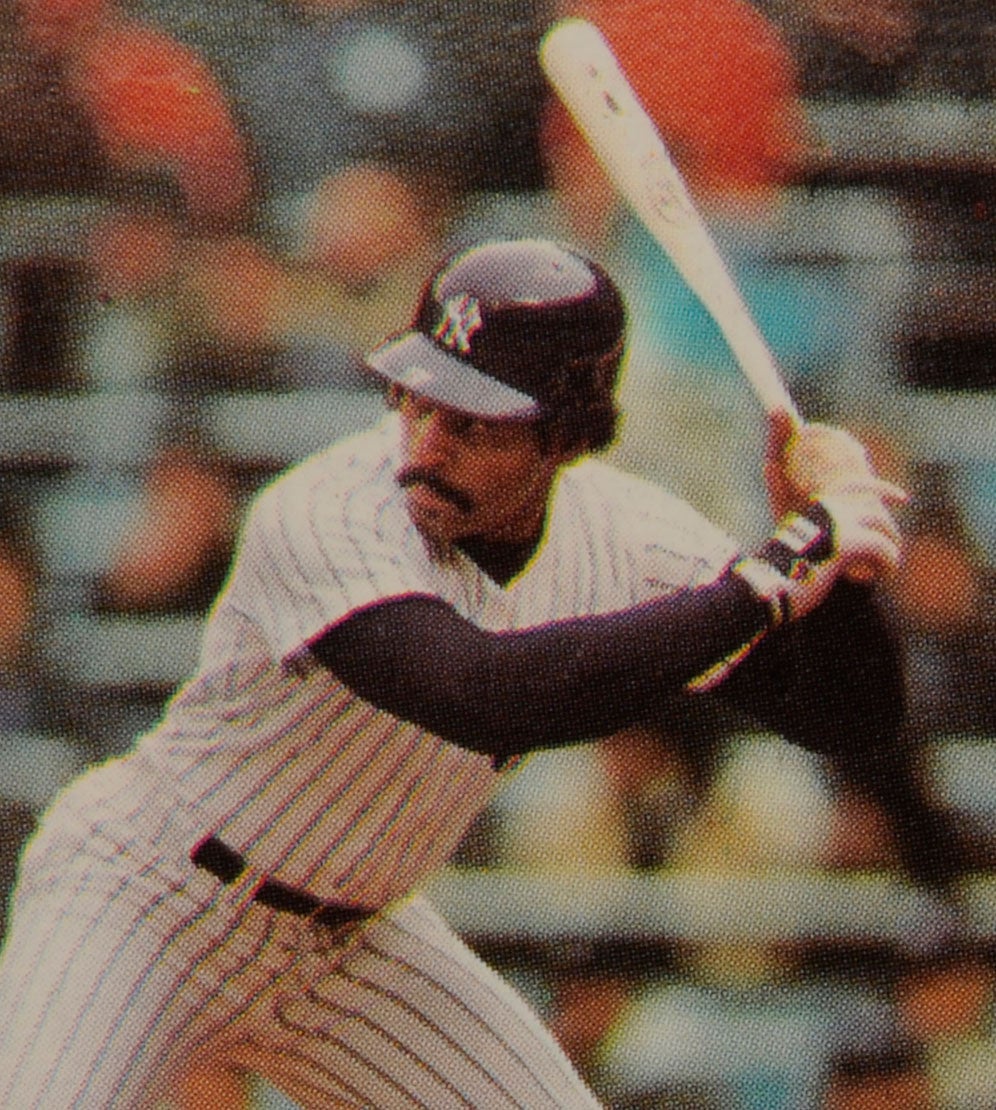

In 1987, Davis nearly did – hitting .346 with 19 homers, 52 RBI and 20 steals through May. A regression was inevitable, but Davis still finished the year with a .293 batting average, 120 runs scored, 37 homers, 100 RBI and 50 steals in just 129 games – becoming the first 30 homer/50 steal player in history.

Davis missed eight games in mid-September after hurting his ribs while crashing into the Wrigley Field wall while making a game-saving catch against the Cubs on Sept. 4. He won his first Gold Glove Award that season for his defense while also earning an All-Star Game selection and a Silver Slugger Award en route to a ninth-place finish in the NL MVP voting.

Davis appeared in what would be his career-best game total in 1988 – 135 – while hitting 26 homers to go with 93 RBI and 35 steals. He won another Gold Glove Award and following that up with his third in 1989, hitting 34 home runs and totaling 101 RBI while hitting .281. But nagging injuries limited his stolen base total to 21, and Davis never topped 35 steals in any season during the rest of his career.

After a short dust-up, Davis and the Reds had settled on a $1.35 million salary with incentives for the 1989 season. Then prior to the 1990 campaign, Davis signed a three-year deal worth a reported $9 million.

“Eric is a player we need to have,” new Reds manager Lou Piniella told the Cincinnati Post. “We’re going to expect him to go out and have fun.”

All the Reds had fun that season, as Piniella led the club to a season where they spent the entire year in first place in the NL West. Davis hit .260 with 24 homers and a team-best 86 RBI. He hit just .174 in the NLCS vs. the Pirates – Davis’ first Postseason games – but had a key RBI groundout in the deciding Game 6, giving the Reds a 1-0 lead in the first inning in a game the Reds would eventually win 2-1.

Then in the World Series, Davis – who had moved to left field late in the season to make room for Billy Hatcher in center – and the Reds steamrolled a heavily favored Athletics team. Davis set the tone in Game 1 with a two-run home run in the first inning – becoming the 22nd player in history to homer in his first World Series at-bat – and Hatcher would eventually hit .750 (9-for-12) with six runs scored.

In Game 4, however, Davis dove in vain for a first-inning ball hit by Willie McGee that went for a double. Davis, whose elbow was jammed into his right side on the play, remained in the game but needed to be helped into the clubhouse after the inning. Blood was discovered in his urine, and he was eventually diagnosed with a lacerated kidney. Reports indicated Davis lost about two pints of blood.

The Reds won Game 4 to end the series – not a moment too soon for Piniella.

“I thought I was going to have to activate myself,” said Piniella, who also nearly lost Hatcher to injury when he was hit on the hand by a pitch from Dave Stewart in the first inning of Game 4.

Davis recovered in time for Opening Day 1991 but struggled all year with health issues. The Reds were unable to replicate their success from the year before and Davis appeared in only 89 games, batting .235 with 11 homers, 33 RBI and 14 steals.

“I’m going to have to take it slow,” Davis told the Cincinnati Enquirer when he returned to action Aug. 26 after his bout with fatigue. “I have to find out where my body is, if I’m going to get tired as fast as I was before I went down.”

On the day before Thanksgiving, the Reds decided that Davis would potentially never be the same player he was before the injury – and traded Davis and pitcher Kip Gross to the Dodgers in exchange for Tim Belcher and John Wetteland.

“I was surprised that it happened,” Davis told the Cincinnati Post. “I have mixed emotions.”

The trade reunited Davis with his old high school rival Darryl Strawberry, who was ensconced in right field for the Dodgers. But Davis and Strawberry appeared in a combined 119 games due to injuries, with Davis – who suffered a fractured wrist among other maladies – batting .228 with five homers, 32 RBI and 19 steals.

The Dodgers finished 63-99 and in last place in the NL West.

“Darryl and Eric were the heart of our club,” Dodgers president Peter O’Malley told the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “Losing the heart of a club is a big, big hit for any team.”

Davis was healthier in 1993 but was hitting .234 with 14 homers, 53 RBI and 33 steals through 108 games when the Dodgers traded him to the Tigers on Aug. 31 in exchange for a player to be named later who turned out to be pitcher John DeSilva. Davis finished the year hitting .237 with 20 homers, 68 RBI and 35 steals.

After agreeing to a one-year deal with the Dodgers worth $2 million in 1993, Davis returned to the Tigers on a another one-year deal for 1994. But after starting the year healthy, Davis was hitting .186 through May 22 when he went on the DL with a pinched nerve in his neck. He played only two more games all year – and after undergoing surgery for a herniated disc opted to retire.

But while on the field at Dodger Stadium during the 1995 NLDS between the Reds and the Dodgers, Davis decided to give the game another chance. He signed with the Reds for one year and $750,000 for the 1996 season and brought back memories of his youth by hitting .287 with 26 homers, 83 RBI and 23 steals.

Following the season, Davis quickly signed a one-year, $2.2 million deal with the Orioles.

“We believe Eric has returned to the All-Star type player he was in the late 1980s,” Baltimore general manager Pat Gillick told the Associated Press.

But once again, Davis’ body had other plans. Davis was hitting .304 with seven homers and 21 RBI through 34 games as Baltimore’s primary right fielder when he was sidelined with what was first diagnosed as a stomach ailment. It was later found that Davis had colon cancer and he immediately underwent surgery, losing one third of his colon in the process.

When he returned to the field in September, Davis was grateful just to be alive.

“This was just the icing on the cake, being able to get back between the lines,” Davis told the AP after returning to the lineup as the Orioles right fielder Sept. 15.

Davis helped the Orioles defeat the Mariners in the ALDS and played in all six games of the ALCS vs. the Indians as Baltimore fell to Cleveland. He was honored with both the Hutch Award and the Roberto Clemente Award in 1997 for his fight to defeat cancer and continue his career.

Davis returned to the Orioles in 1998 on a one-year, $2.5 million deal and flashed his old form – hitting a career-high .327 with 28 homers and 89 RBI in 131 games. He then signed a two-year, $8 million deal with the Cardinals but was limited to 58 games in 1999 due to injuries.

Davis hit .303 in 92 games as a bench player in 2000 – including a .391 batting average against left-handers – helping St. Louis advance to the NLCS. He signed with the Giants for the 2001 season, hitting .205 in 74 games and announcing during the season that the 2001 campaign would be his last.

Over 17 big league seasons, Davis hit .269 with 282 homers, 934 RBI and 349 stolen bases. Davis is the only player in history with more than 275 homers and 300 steals with fewer than 1,500 career hits (1,430).

In short, Davis made every one of his big league games count.

“It’s hard for me to sit down and watch,” Davis said during one of his stints on the disabled list. “It’s hard because it’s killing me not to play.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

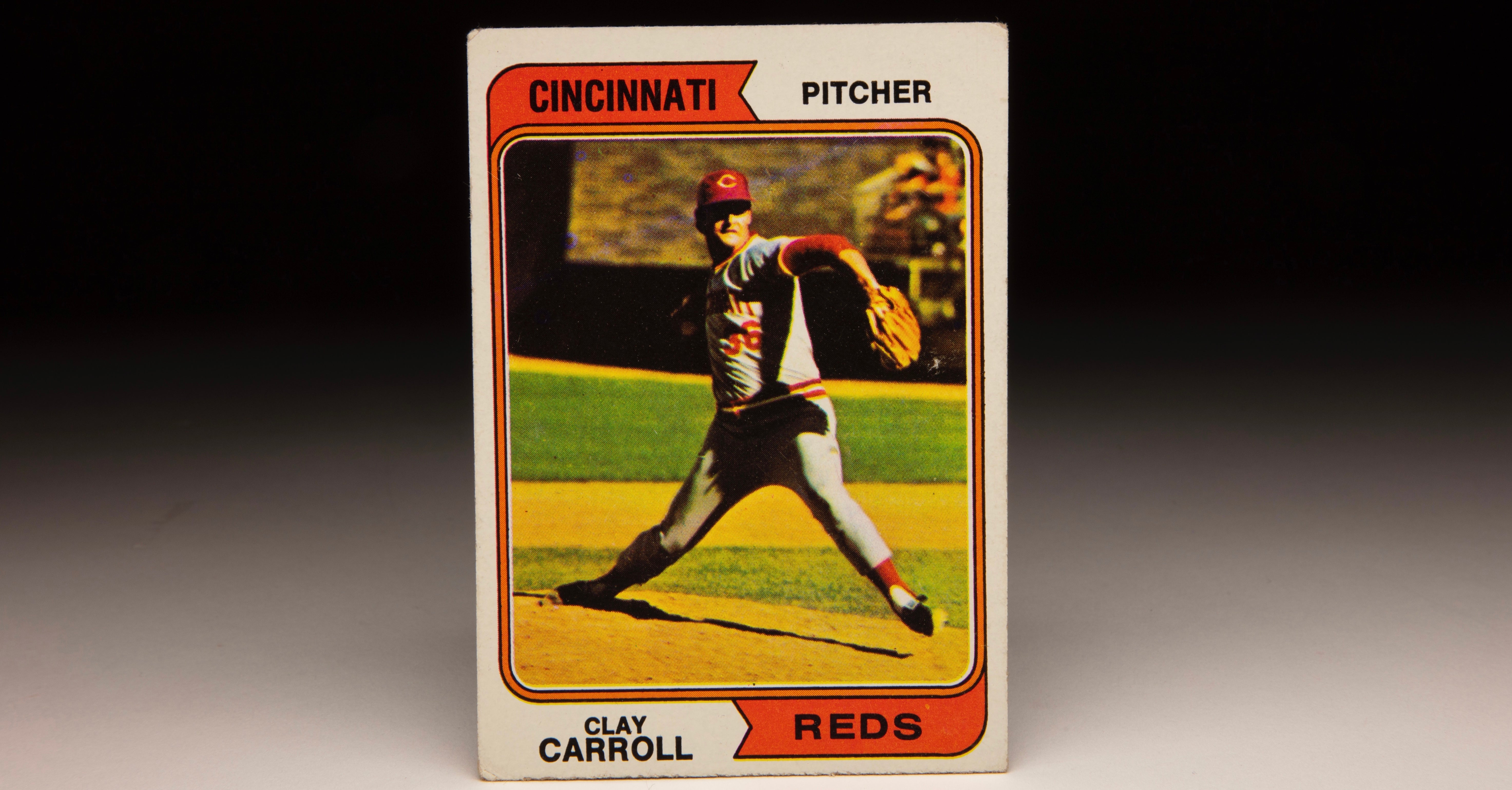

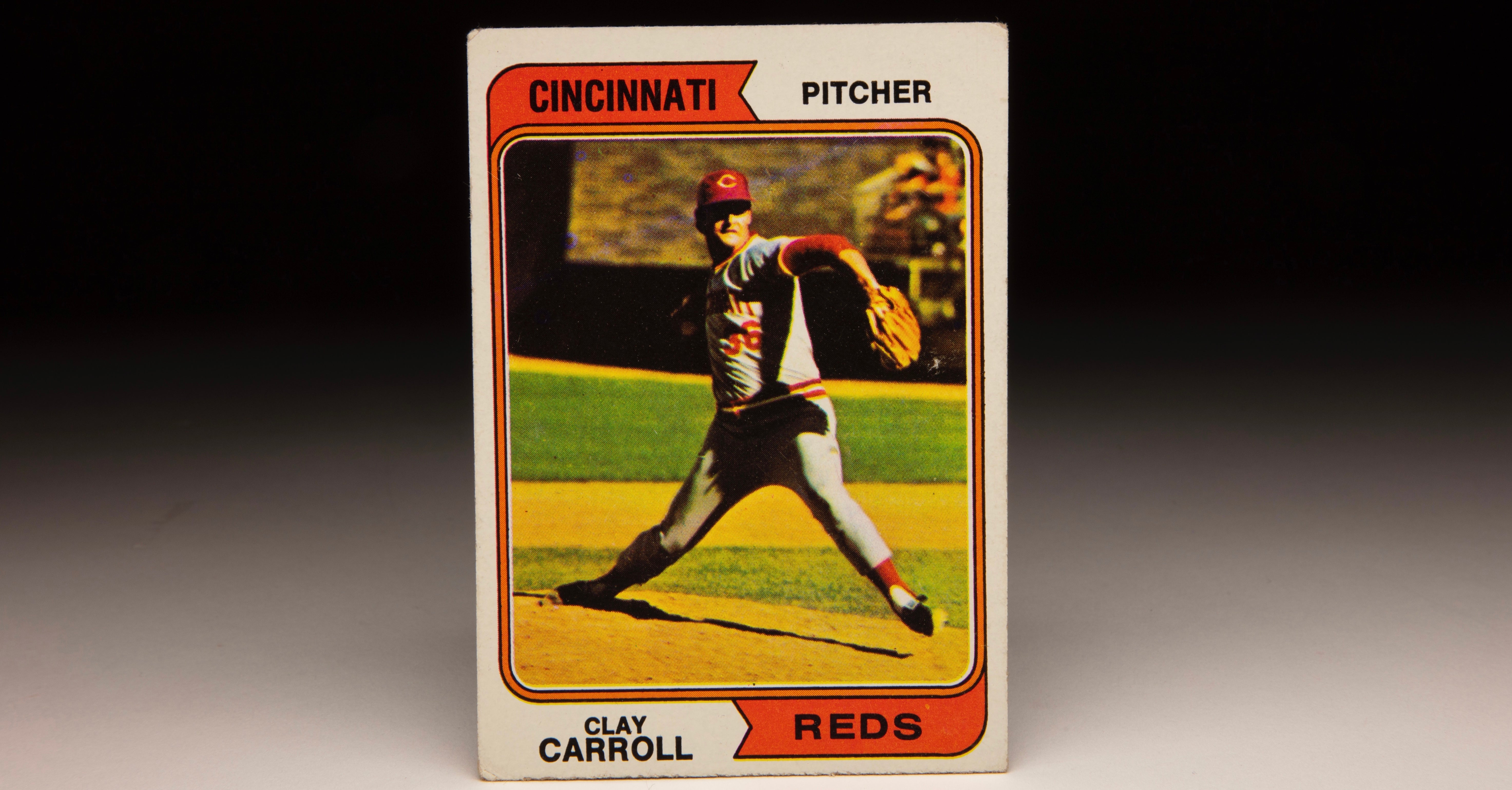

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Clay Carroll

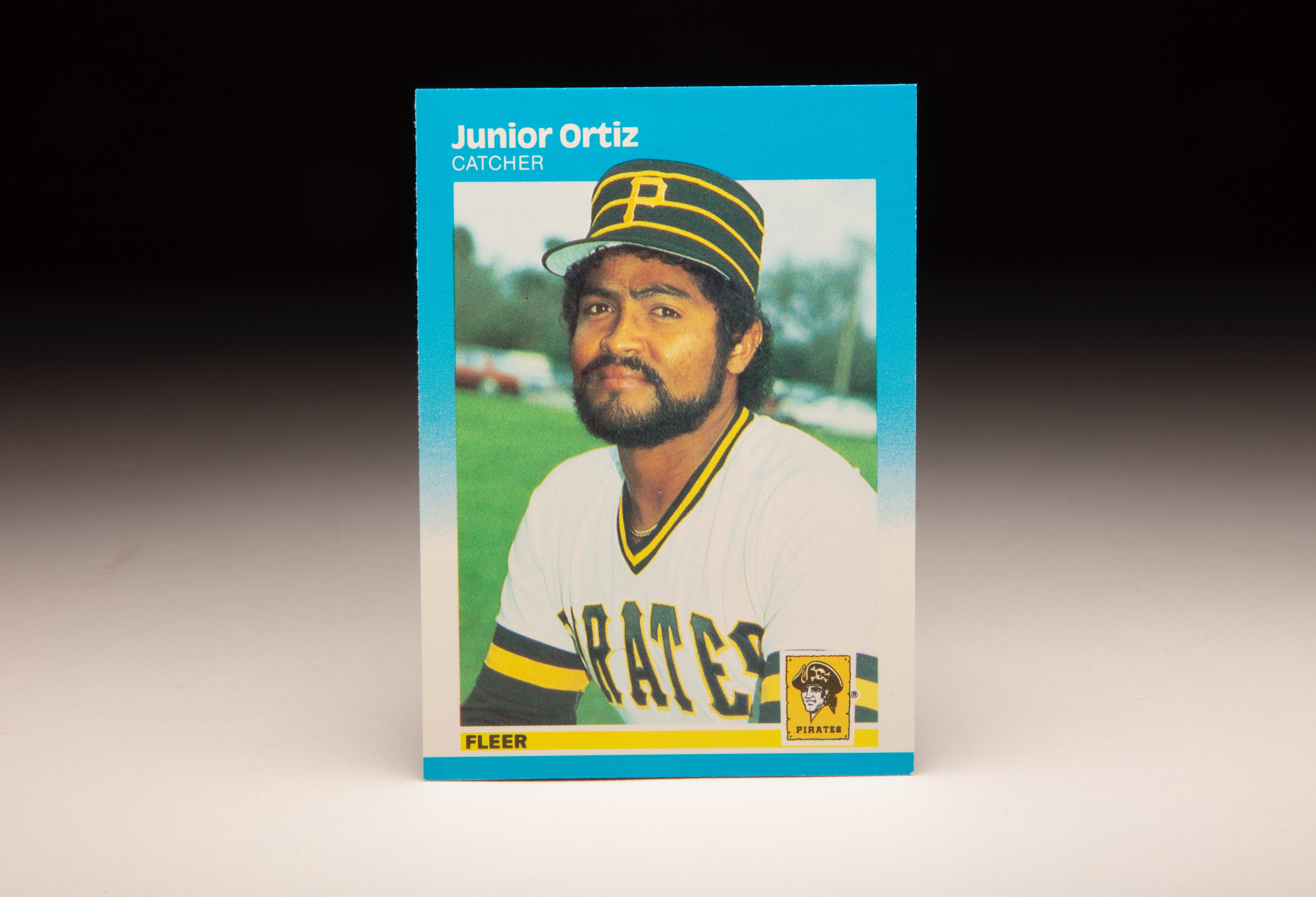

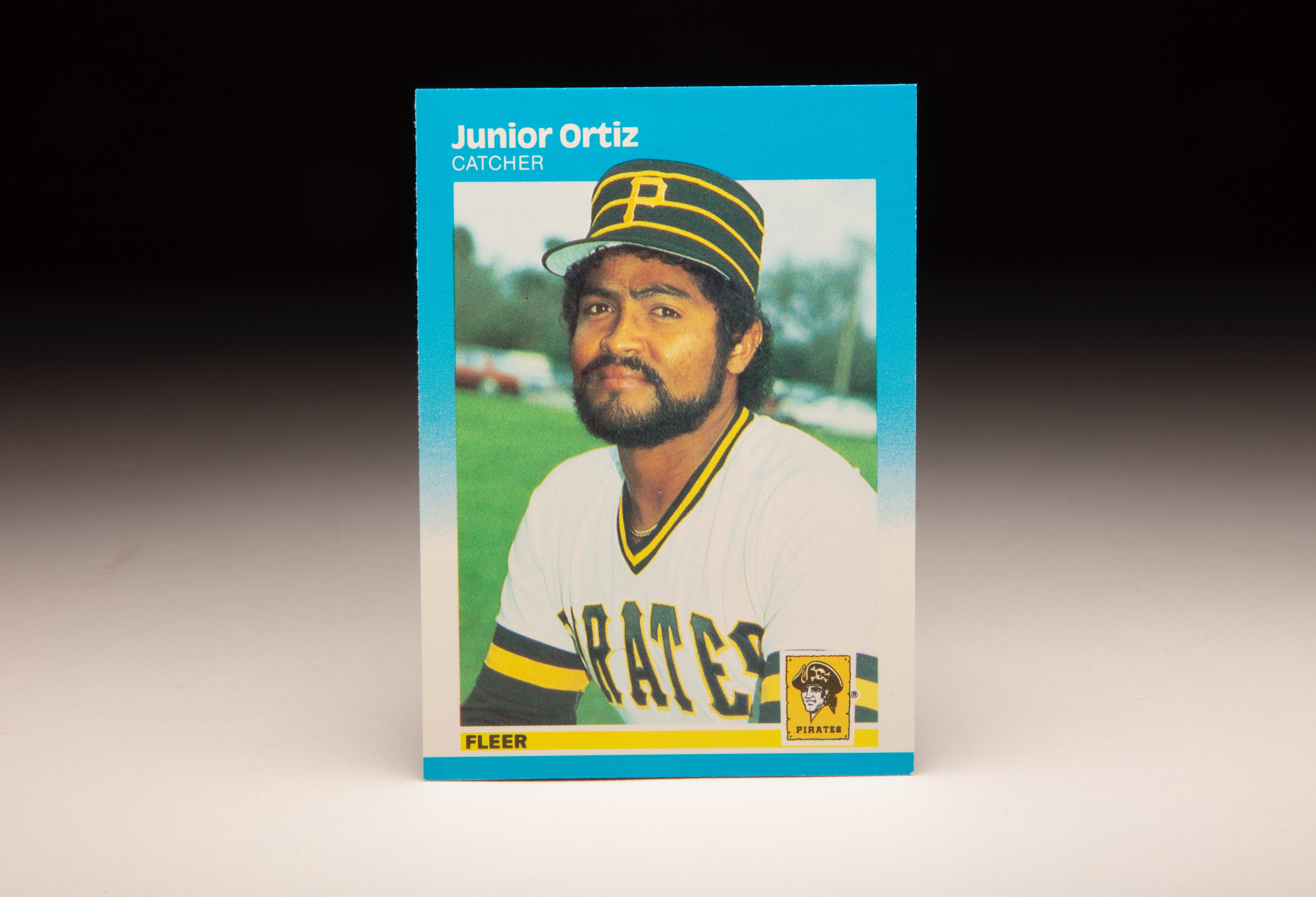

#CardCorner: 1987 Fleer Junior Ortiz

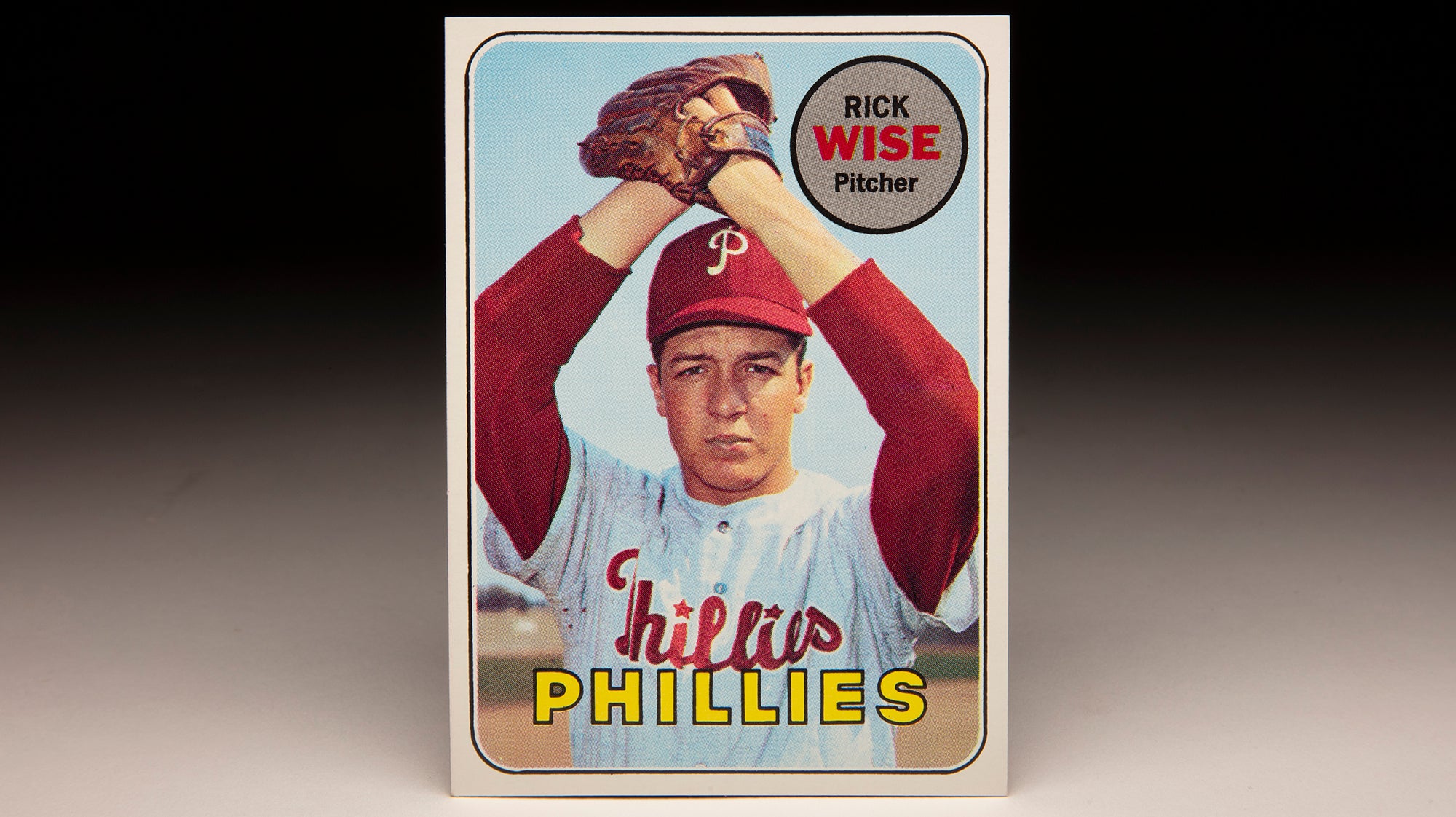

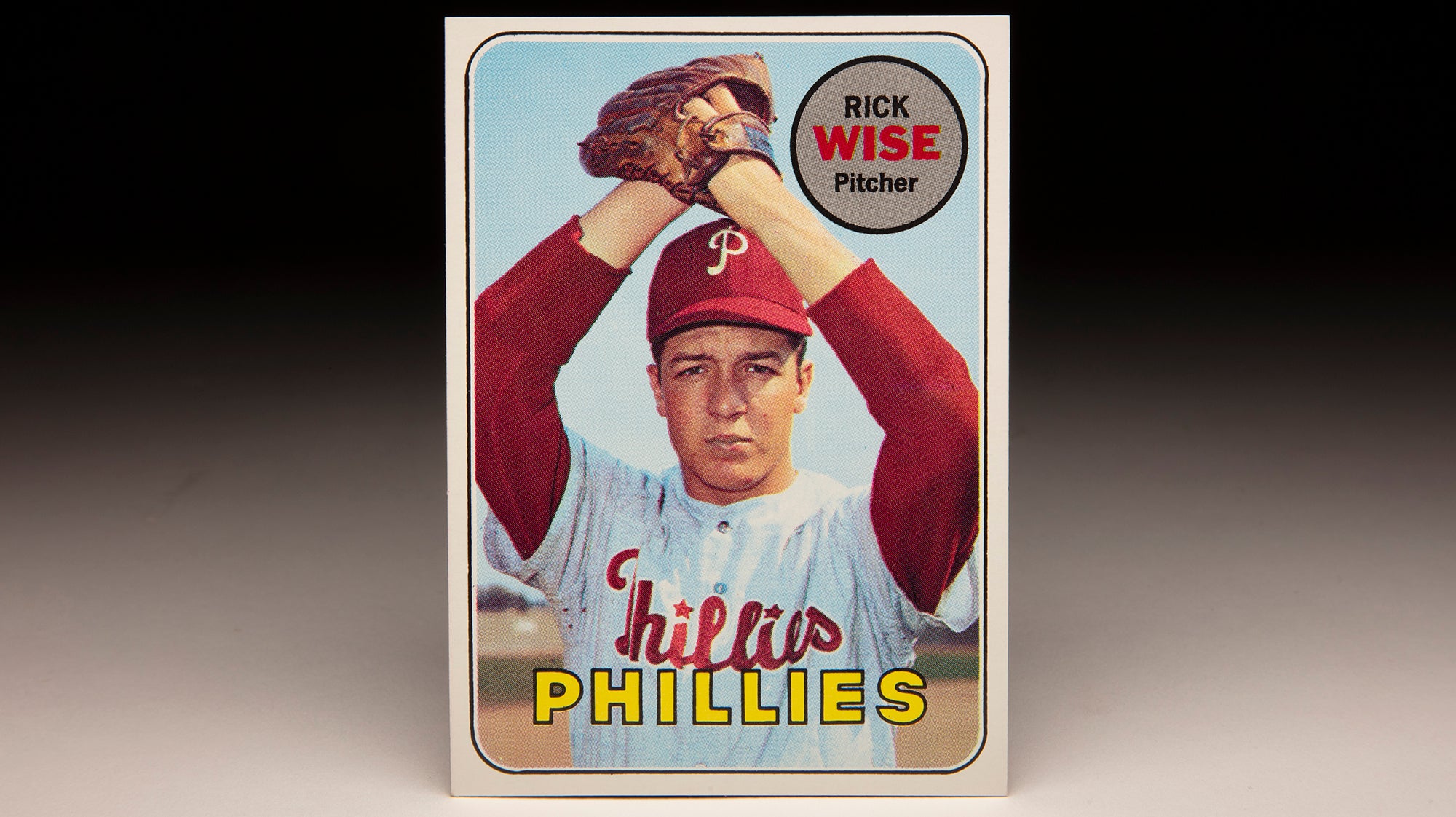

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Rick Wise

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Clay Carroll

#CardCorner: 1987 Fleer Junior Ortiz

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Rick Wise