- Home

- Our Stories

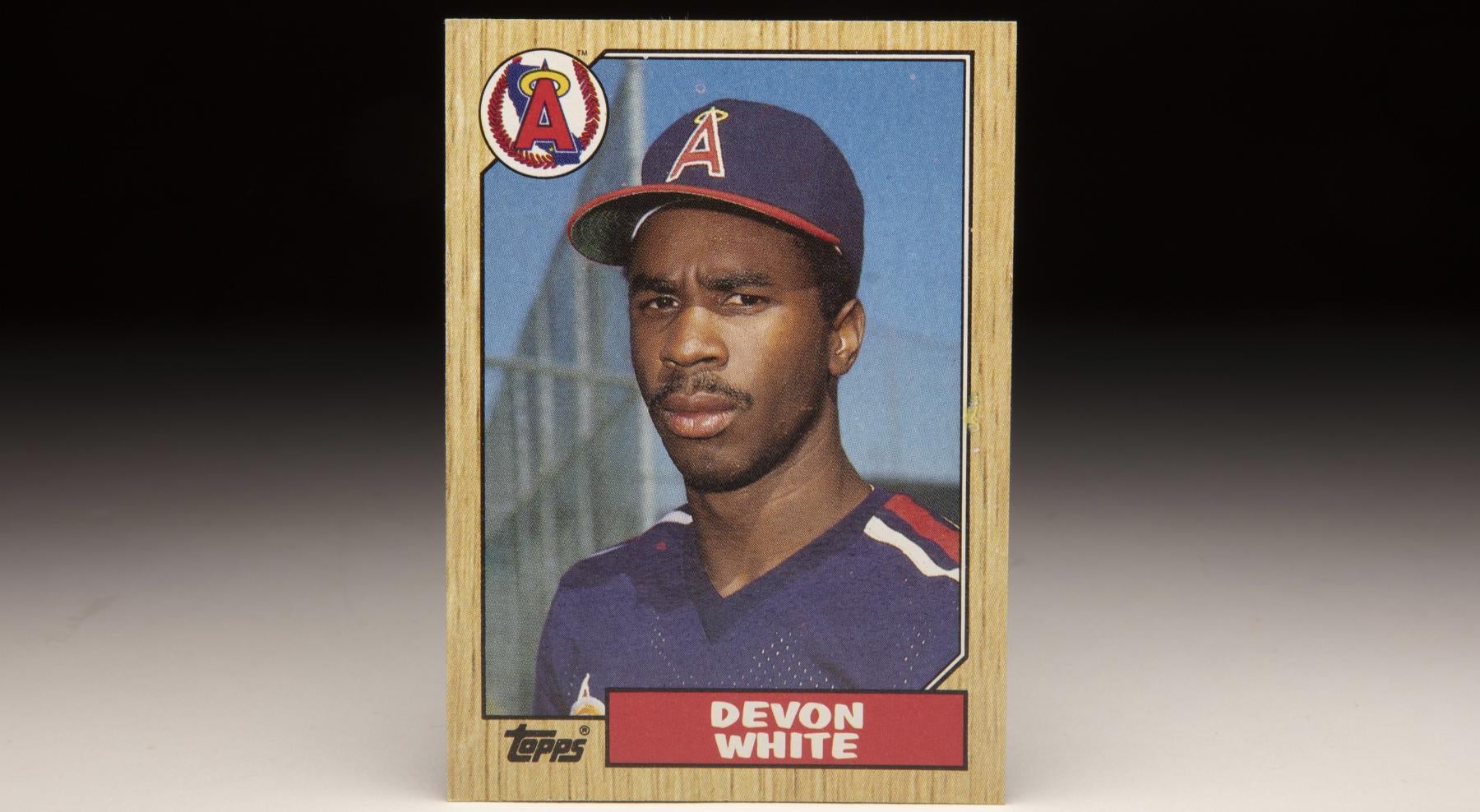

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Devon White

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Devon White

Devon White is one of only 23 players in history with at least 200 home runs and 300 steals – and is one of just two players on that list, along with Derek Jeter, who played on at least three World Series winners.

But White’s legacy might be even more prominent had replay review existed in the 1992 World Series. That, in turn, would have likely made him a part of the second triple play in the history of the Fall Classic – largely due to an incredible catch by White, who was one of the game’s top center fielders.

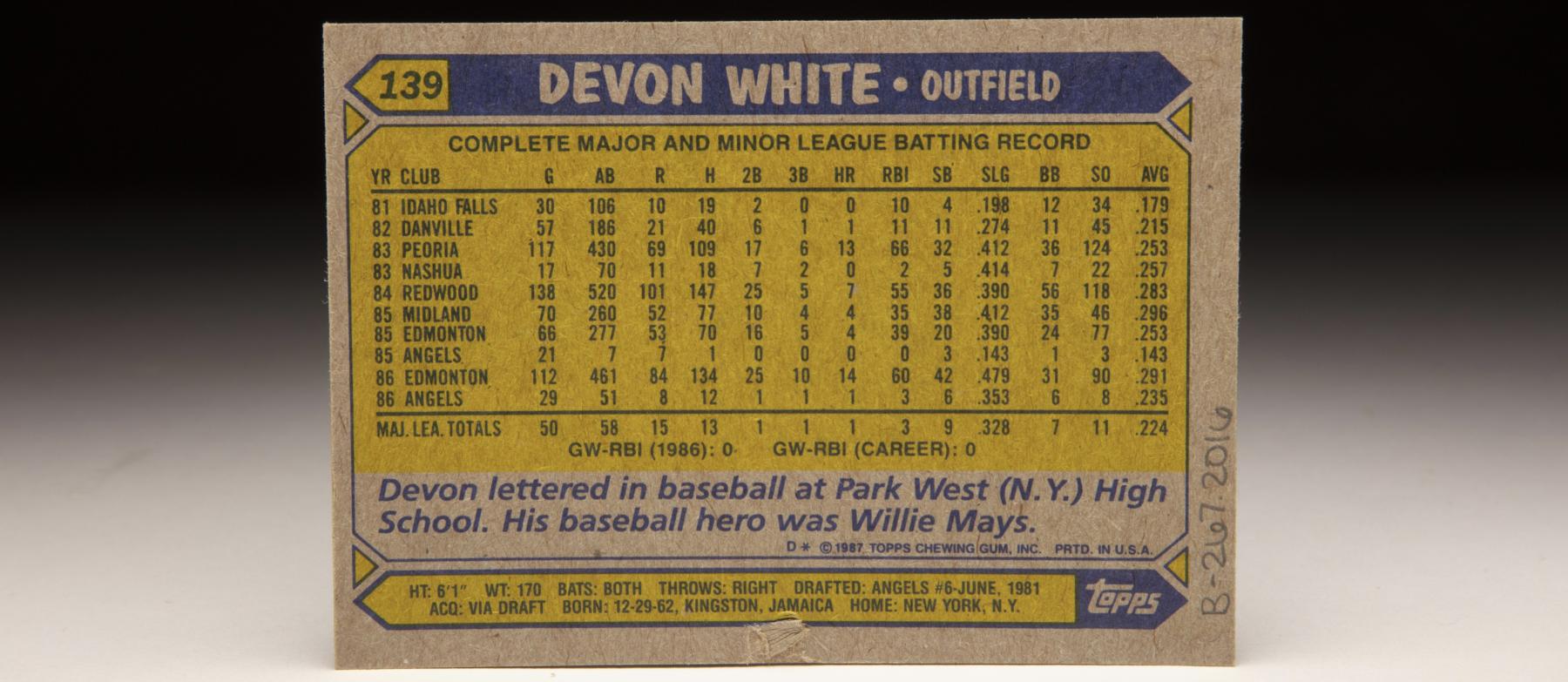

Born Devon Markes Whyte on Dec. 29, 1962, in Kingston, Jamaica, Whyte and his family came to the United States a decade later and had their surname changed to “White” due to a paperwork error. He attended Park West High School in Manhattan, starring in baseball and basketball while growing up in and around the Bronx. Selected in the sixth round of the 1981 MLB Draft by the Angels, White turned down college basketball scholarship offers for a chance to play baseball.

White struggled in his first two minor league stops with Idaho Falls in 1981 and Danville a year later. But while in Danville, he made an impression on the Angels’ front office that was worth more than any stat line.

On July 19, 1982, White and his Danville teammates were eating breakfast in a coffee shop in Davenport, Iowa – another Midwest League outpost. The driver told White they would leave in a few minutes after he finished his breakfast, and that he would be out soon to warm up the bus.

White, who had finished eating, left the restaurant and boarded the bus. Trying to be helpful, he started the vehicle – which had been left in gear by the driver.

Moments later, the bus crashed into a cement wall that was separating the parking lot from a swimming pool.

The Angels sent White back home to New York while they tallied the damages – an estimate that came to about $10,000.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“I’m going to enroll in junior college,” White was quoted by United Press International as telling Angels executive Bill Bavasi. “I’m going to get a job and pay for the damage I caused. No matter what it costs, I want to pay for all the damage.”

Bavasi and the Angels paid the bills – and knew then they had someone special in White.

“He’s not only a fine looking prospect,” Al Goldis, the Angels scout who signed White, told UPI, “but he’s a young man with unusual character and integrity,”

In 1983, White began to flash the power/speed combination that would bring him to the big leagues. White hit .254 with 13 homers, 66 RBI and 32 steals in 117 games for Class A Peoria of the Midwest League, earning a promotion to Double-A Nashua.

White returned to Class A ball in 1984 with Redwood of the California League, hitting .283 with 36 steals and 101 runs scored in 138 games. That performance put White on the Angels’ top prospect list, and he received an invitation to Spring Training in 1985.

“This is the best crop of young players I’ve ever seen in an Angels camp,” Dodgers scout Mel Didier told the Los Angeles Times, singling out White for special praise.

White began the 1985 season with Double-A Midland and was leading the Texas League with 38 steals – while hitting .296 in 70 games – when he was promoted to Triple-A Edmonton. He stole 21 more bases for the Trappers, finishing the minor league season with a .274 batting average, 59 steals and 105 runs scored in 136 games.

On Sept. 2, 1985, White made his big league debut with the Angels as a defensive replacement in left field. He would play in 21 games – mostly as a pinch-runner or late-inning defensive sub – as the season wound down, getting his first start and recording his first hit in the season’s final game.

But with Gary Pettis coming off his first Gold Glove Award in center field, the Angels had the luxury of giving White more time in the minors in 1986. After another impressive performance in Spring Training, the switch-hitting White was sent back to Edmonton, where he hit .291 with 14 homers, 42 steals and 84 runs scored in 112 games. He returned to the Angels on Aug. 31, getting called up just in time to qualify for the postseason rosters as the Angels were chasing the AL West title.

Playing nearly every day down the stretch – sometimes starting and other times coming off the bench – White hit .235 with eight runs scored and six steals in as many attempts. The Angels clinched the division with more than a week left in the season, setting the stage for a memorable ALCS vs. the Red Sox.

White appeared in Games 1, 3 and 4 against Boston, scoring the tying run in the bottom of the ninth of Game 4 when – as a pinch runner for Bob Boone – he crossed the plate when Brian Downing was hit by a Calvin Schiraldi pitch. The Angels went on to win 4-3 in 11 innings, taking a three-games-to-one lead.

Game 5 would go down as one of the most thrilling games in history.

White entered the game as a pinch runner for George Hendrick in the seventh inning and scored on a Rob Wilfong double as the Angels eventually took a 5-2 lead. Staying in the game in right field, White singled in the eighth but was caught stealing, leaving the Angels with a three-run lead and three outs to get to advance to the World Series.

But in the top of the ninth, Don Baylor’s two-run homer off Mike Witt cut the lead to 5-4. Witt got Dwight Evans to pop up for the second out, but Angels manager Gene Mauch then turned to reliever Gary Lucas – a lefty – to face left-handed hitting Red Sox catcher Rich Gedman.

Lucas proceeded to hit Gedman, bringing up Dave Henderson and bringing in reliever Donnie Moore. Henderson then homered to left field, leaving the crowd at Anaheim Stadium stunned and the Red Sox with a 6-5 lead. The Angels, however, tied the game in the bottom of the ninth on a single by Wilfong – and had the bases loaded with only one out. But Steve Crawford retired Doug DeCinces and Bobby Grich to end the threat.

After a scoreless 10th inning – White struck out against Crawford – Henderson hit a sacrifice fly to score Baylor in the 11th. Schiraldi retired the side in order in the bottom of the inning, sending the series back to Boston – where the Red Sox won both games by a combined score of 18-5 to advance to the World Series.

White, however, had made an impression on the game’s October stage.

“Devon White has super physical ability,” Angels general manager Mike Port told the Los Angeles Times. “Right now, he’s on a very fine, fine line. Devon White is very, very close to waking up and finding out what this game is all about.”

White opened the 1987 season in left field before moving to right and eventually to center, replacing the slumping Pettis. White finished the year with a .263 batting average, 24 homers, 87 RBI, 32 steals and 103 runs scored. He led all big league outfielders with 424 putouts and finished two off the assists lead with 16.

White finished fifth in the AL Rookie of the Year balloting. His WAR – 5.6 – was better than any other rookie in either league. But the Angels slid to last place in the AL West despite the infusion of young talent like White and Wally Joyner.

Cookie Rojas replaced Mauch as manager in 1988, but in the season’s eighth game White tore cartilage in his right knee while sliding into second base. He played through the injury until May when he underwent arthroscopic surgery, sidelining him for a little more than a month.

White finished the year hitting .259 with 11 homers, 76 runs scored and 51 RBI in 122 games – and won his first Gold Glove Award. But the Angels finished with 75 wins for the second straight year.

“Devo’s a gamer,” Angels teammate Mark McLemore told the Los Angeles Times about White’s ability to play through pain. “He’s gonna do it until he can’t do it anymore.”

White played in 156 games in 1989, hitting .245 with 12 triples, 12 homers, 56 RBI, 44 steals and 86 runs scored while earning his second Gold Glove Award and first All-Star Game selection. But in 1990, White struggled for the first three months of the season and was hitting .213 when he was optioned to Triple-A in July. After three weeks in Edmonton – where he hit .364 – White was recalled but never got hot, finishing the year with a .217 batting average and 21 steals in 125 games with the Angels.

On Dec. 2, the Angels shipped White, Willie Fraser and Marcus Moore to the Blue Jays in exchange for Junior Félix, Luis Sojo and a minor leaguer.

“One of our problems last year was outfield defense,” Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick told the Associated Press. “We got (White) for defense. We’re not worried about his hitting. We feel we have enough offense to carry Devon White, no matter what he hits.”

Gillick was correct about the defense: White would win a Gold Glove Award in each of his five years in Toronto. But on offense, Gillick underestimated his new center fielder. In his first year with the Blue Jays, White hit .282 with 110 runs scored, 181 hits, 40 doubles, 10 triples, 17 homers, 60 RBI and 33 steals. The Blue Jays won the AL East title but lost to the Twins in the ALCS despite a .364 batting average and three steals by White.

In 1992, White’s batting average dipped to .248 but he still scored 98 runs to go with 17 homers, 60 RBI and 37 steals. White hit .348 with five walks as Toronto defeated the Athletics 4-games-to-2 to advance to its first World Series against Atlanta. There, White put on a show on the national stage.

With the series tied at a game apiece and Game 3 scoreless in the fourth inning, the Braves’ Deion Sanders led off with an infield single that eluded pitcher Juan Guzmán. Terry Pendleton followed with a single to right field, sending Sanders to second base and bringing up David Justice.

Guzmán’s first pitch was low and out over the plate, and Justice crushed it to dead center field. White, shading Justice a bit toward right field, turned with the crack of the bat and – seemingly unfazed by the situation – calmly ran toward the SkyDome fence. A step away from a collision, White jumped and snatched the ball out of the air – his glove just inches away from the wall – before crashing into the barrier.

Upon landing, White fired a strike to second baseman Roberto Alomar, who was behind second base. Alomar threw on to John Olerud at first base, but Pendleton – who was retreating to the bag – had already been called out by second base umpire Bob Davidson for passing Sanders on the base paths.

Olerud then fired to third baseman Kelly Gruber, and Sanders suddenly found himself caught in a rundown. Gruber ran Sanders back to the bag and dove at him at the last second, apparently tagging Sanders on the right ankle. But Davidson, who was moving as he made the call due to the rundown, missed the tag and called Sanders safe.

It would have been just the second triple play in World Series history, following Bill Wambsganss’ unassisted three outs in Game 5 for Cleveland in 1920. And it would have elevated White’s catch to World Series aristocracy.

“Devon White is the trade we made that nobody talks about,” Gillick told the New York Daily News. “But he’s the best center fielder in the American League.”

The Blue Jays went on to win the World Series in six games, with White scoring the go-ahead run in the top of the 11th inning of Game 6 on Dave Winfield’s memorable double down the left field line.

The Blue Jays were even better in 1993 as White hit .273 with 116 runs scored, 42 doubles, 15 homers, 52 RBI and 34 steals. White hit .444 with a series-high 12 hits in the six-game ALCS win over the White Sox. White then hit .292 with seven RBI and eight runs scored in Toronto’s six-game win over the Phillies in the World Series.

The Blue Jays were denied a chance at a three-peat when the strike ended the 1994 season, but White hit .270 with 67 runs scored in 100 games while overcoming injuries to his hip and Achilles tendon. Injuries and a shortened season limited White to 101 games in 1995 but he still managed to hit .283 with 61 runs scored and 53 RBI.

With his contract expiring, White became a free agent and signed a three-year deal with the Marlins worth a reported $9.9 million.

“We were amazed at how quickly this thing happened,” Marlins general manager Dave Dombrowski told the Miami Herald. “So many teams wanted him, we had to move fast.”

White put up numbers in line with his best seasons in Toronto in 1996, hitting .274 with 37 doubles, 17 homers, 84 RBI, 22 steals and 77 runs scored. Though his 1995 Gold Glove would be the seventh and last of his career, White was still among the best outfielders in the game.

But in 1997, White missed virtually the whole month of May with a knee injury and then was sidelined for almost all of June and July with a pulled calf muscle. He returned to full strength in August and hit .245 on the season with 37 runs, helping the Marlins win the NL Wild Card.

Once again, White was at his best in the postseason. His sixth-inning grand slam in Game 3 of the NLDS vs. the Giants turned a 0-1 Marlins deficit into a 4-1 lead, and Florida went on to sweep the series. He scored four runs in the Marlins’ six-game win over Atlanta in the NLCS before recording eight hits in the World Series against Cleveland to help the Marlins win a thrilling seven-game series.

But almost immediately after the end of the World Series, the Marlins began dismantling their team. On Nov. 18, 1997, the Marlins traded White to the Diamondbacks in exchange for Jesus Martínez, a minor league pitcher who Arizona had just selected from the Dodgers in the Expansion Draft and the younger brother of Hall of Famer Pedro Martínez. Jesus Martínez would never play in the big leagues.

White, who was living in Phoenix at the time, was at a Phoenix Suns basketball game when the trade was announced and received an ovation when he stood up and showed off a Diamondbacks jersey.

White gave the Diamondbacks all they wanted and more in their inaugural season, hitting .279 with 22 homers, 85 RBI and 22 steals while becoming the team’s first All-Star Game representative. Soon after the season ended, White – a free agent – signed a three-year deal with the Dodgers worth a reported $12.4 million, a pact that included a team option for a fourth year.

White, who would be 36 years old at the start of the 1999 season, hit .268 in 134 games, totaling 14 homers, 68 RBI and 19 steals. But on May 2, 2000, White suffered a partial tear of his left rotator cuff while diving for a ball in the Dodger Stadium outfield in a game against the Braves. White would appear in just 25 more games that season.

On Feb. 24, 2001, the Dodgers sent White to the Brewers in exchange for Marquis Grissom and pitcher Ruddy Lugo in a deal that was essentially a swap of veteran center fielders. White hit .277 with 14 homers, 47 RBI and 18 steals in 126 games in 2001, but the Brewers declined to pick up his 2002 option.

He would not play in the big leagues again.

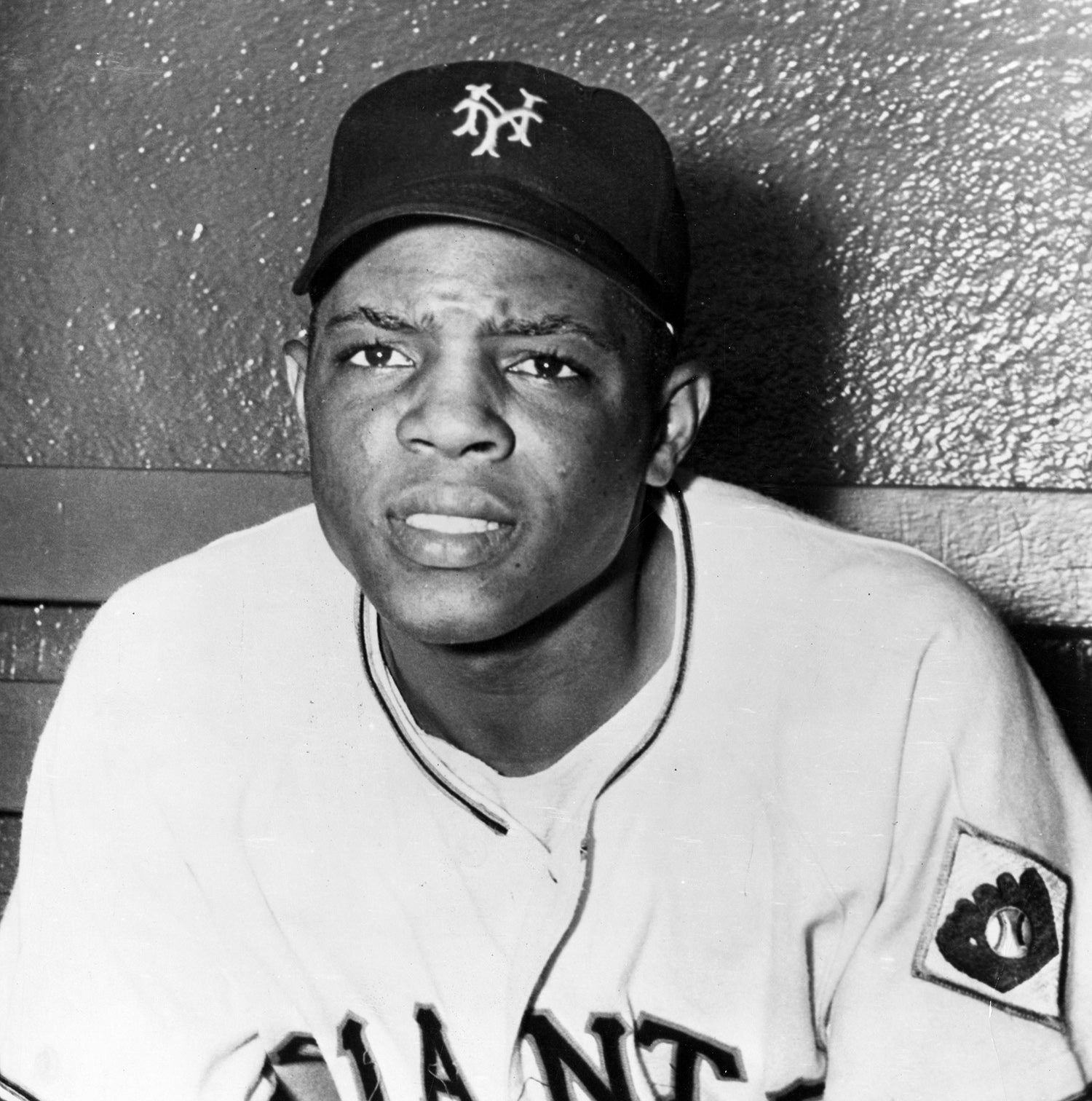

White, who later served as a hitting coach with Toronto’s Triple-A team in Buffalo, ended his 17-year career with a .263 batting average, 1,125 runs scored, 378 doubles, 208 homers and 346 steals. His career defensive WAR of 16.7 ranks fourth all-time among retired center fielders, behind only Andruw Jones (24.4), Paul Blair (18.8) and Willie Mays (18.2).

“He was born to play the outfield,” Bill Bavasi, the Angels’ farm director when White was their top prospect, told UPI. “And he can fly.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

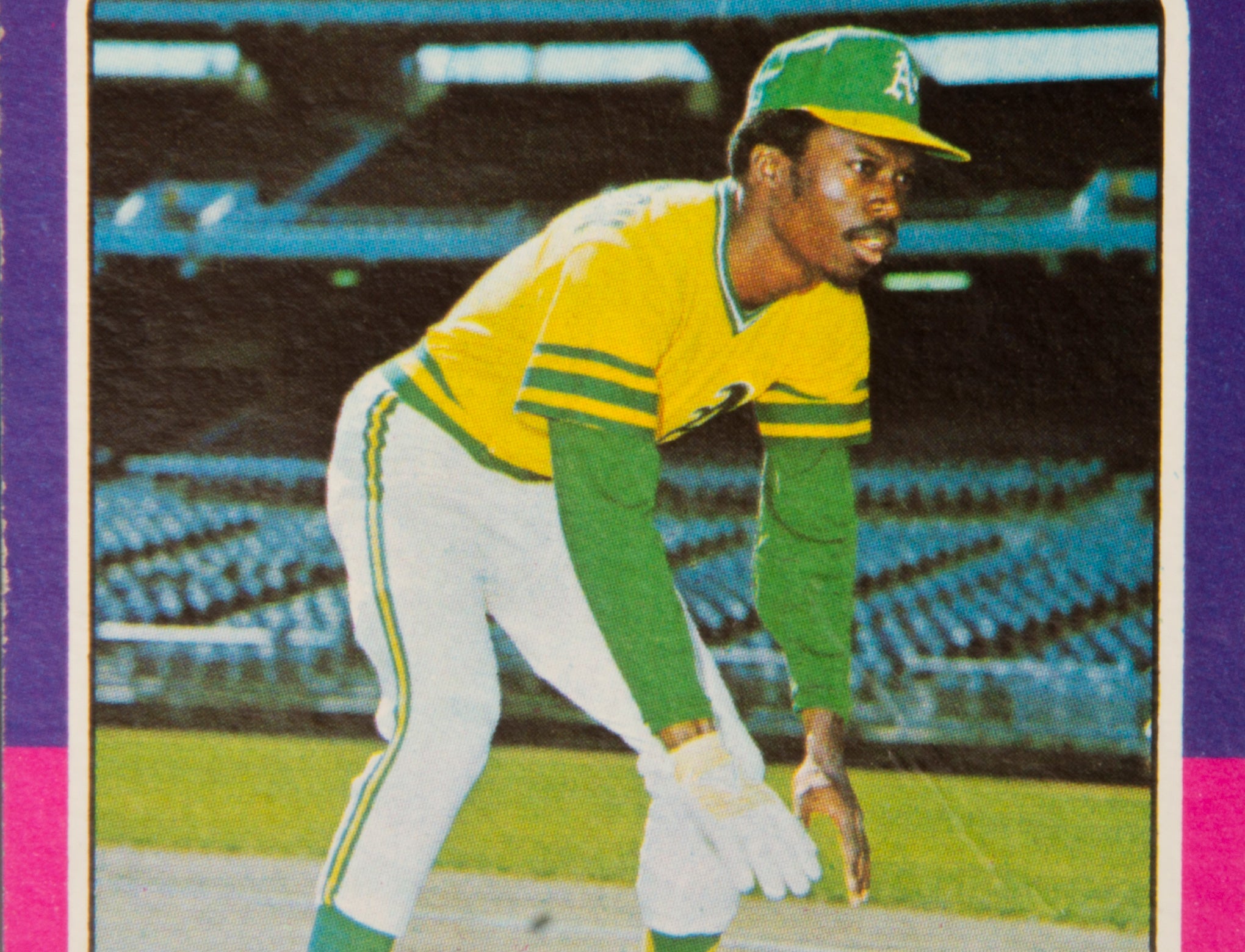

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington

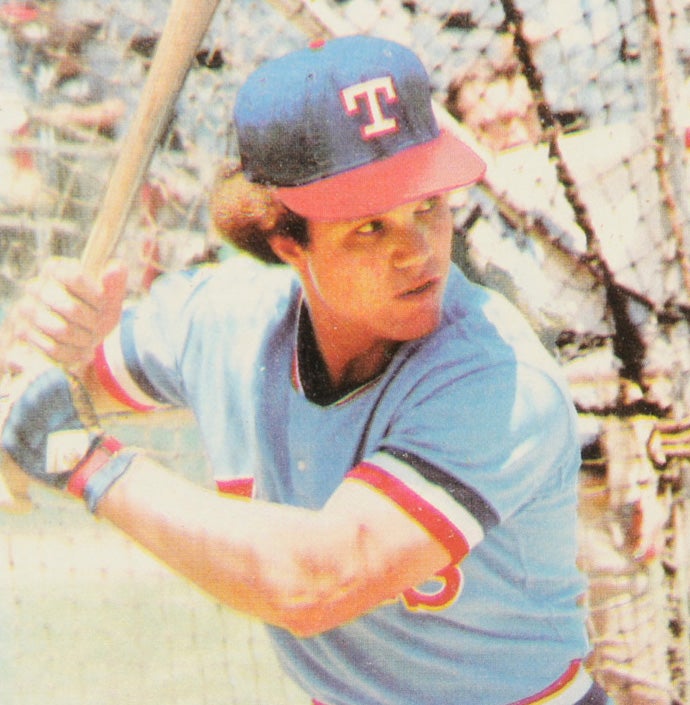

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills