- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Bobby Bonds

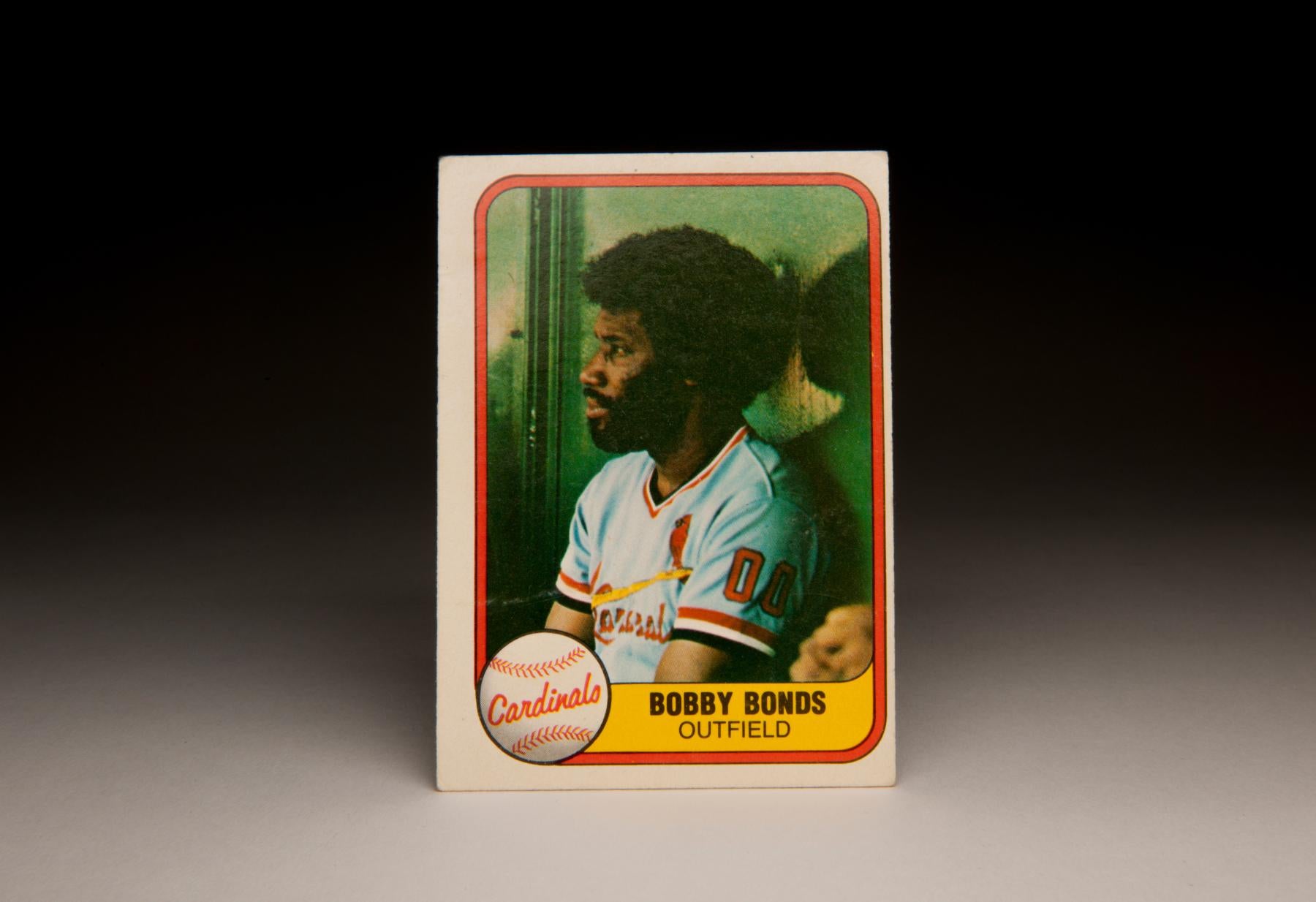

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Bobby Bonds

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With his head propped against the dugout wall, Bobby Bonds looks tired on his 1981 Fleer card. The beard that he has chosen to grow for the first time in his professional career makes him look old, older than his 35 years. Even the uniform seems out of place. I mean, who remembers Bobby Bonds playing for the St. Louis Cardinals? That’s not the Bonds that I know.

Every player ages. That is an unquestionable and unavoidable fact. But Bonds appears to have aged faster and more considerably than most. Perhaps it’s the frequent travels of his career, which have taken a toll on his body. Or it could well have been the effects of a fast-paced 1970s lifestyle.

By 1981, Bonds’ playing abilities had so eroded that it was easy to forget just how phenomenal he was in the prime of his career. At his peak, Bobby Bonds was just about as good as there was to be found in either league. He was a premier five-tool talent who could run with anyone, hit with Ruthian power, and pursue fly balls with unmatched aggressiveness and speed. He was the Mike Trout of an earlier era, a player who seemed destined for the Hall of Fame.

Bonds’ professional career dates back to 1964, when he signed with the San Francisco Giants. Shockingly, he almost quit during his first season in the minor leagues. Assigned to a team in Lexington, N.C., he was the only black player on the team. Due to Jim Crow segregation, he couldn’t eat with the teammates or stay with them on many Southern city road trips. But his manager, former major leaguer Max Lanier, sat down with Bonds and convinced him to keep playing.

Given his talents, it was no surprise that that Bonds moved up steadily within the Giants’ system. When he started the 1968 season by hitting .370 at Triple-A Phoenix, the Giants realized that he was ready. Shortly after his call-up, Bonds delivered his first hit, which turned out to be a grand slam.

Given a full season in San Francisco in 1969, Bonds blossomed. He blasted 32 home runs, stole 45 bases, and drew 81 walks. Bonds drew comparisons to one of his veteran teammates, a fellow named Willie Mays. Being compared to Mays, while flattering, can also be a kiss of death. Who can live up to such lofty expectations? Remarkably, Bonds did not shrink under the spotlight of such a comparison. Over the first five full seasons of his career, Bonds reached the 30 homer/30 stolen base club twice, led the league in runs twice, received MVP votes three times, won two Gold Glove Awards and earned selection to two All-Star teams.

By the middle of the 1973 season, when Bonds was named MVP of the All-Star Game, some sportswriters were beginning to refer to him as the best player in the game. In a season that featured star players like Johnny Bench, Cesar Cedeno, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Willie Stargell in their primes, that was saying an awful lot. As a leadoff man, Bonds skillfully drew walks and posed particular trouble for the opposition because of his incredible power. He sometimes struggled with the curve ball, but he could handle any pitcher’s best fastball. As a base runner, he dazzled everyone, from teammates to opponents to fans. “He was the best-looking runner I’ve ever seen,” Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda once told the Associated Press. “Nobody stole second base as easily as Bobby Bonds.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As well as Bonds played for San Francisco over his first five full seasons, he did draw criticism on two counts. He struck out excessively, particularly for a leadoff man, leading the league in that unwanted category in 1969, 1970 and 1973. Bonds also had a tendency to slow down on routine ground balls and pop-ups. The latter point became such an issue that Pittsburgh Pirates superstar Roberto Clemente felt motivated to talk to Bonds in 1972. Clemente stressed to the young Bonds the importance of playing hard at all times.

Off the field, another concern persisted. Bonds enjoyed living life to the fullest. In an era where many players drank and smoked, Bonds did both. Bonds admitted to the drinking, but categorically denied whispers of drug use. “I have never in my life messed with any kind of drug,” Bonds told the New York Daily News. “I never fool with it and I never will.”

The drug rumors were unsubstantiated, but his problems with Giants management became a matter of record. In 1974, he butted heads with Giants manager Charlie Fox, an old school, no-nonsense sort. One day, Fox became angry when Bonds decided to skip both infield and batting practice. The two exchanged hostile words, though Bonds claimed he and Fox quickly moved past the argument.

When Fox lost his job to Wes Westrum in midseason, some speculated that Bonds would remain in San Francisco long-term. That turned out not to be the case. With his offensive numbers slipping, Giants management believed that Bonds’ hard way of living was taking its toll. So the Giants did something that had been considered unthinkable as recently as 1973: During the winter, they made a blockbuster trade, sending Bonds to the New York Yankees for Bobby Murcer.

Giants fans despised the decision to trade Bonds, who was more talented and more athletic than Murcer. Predictably, the fan base in New York held the opposite viewpoint. Yankee fans loved Murcer; they regarded Bonds as an intruder. Some have speculated that racism was involved, but I don’t think it was that. Murcer was just so popular, so beloved, that any such trade would have been treated with rancor, no matter the player coming back to New York. What I do know is this: As a young Yankee fan at the time, I had nothing against Bonds, but I simply hated the decision to trade away Murcer.

In spite of the cold greeting waiting for him in New York, Bonds played well over the first half of the 1975 season. In fact, he picked up enough votes in the fan balloting to earn a starting role on the American League’s All-Star team.

A development in August changed the tenor of Bonds’ season. On August 1, the Yankees fired the patient Bill Virdon as manager and replaced him with the more demanding Billy Martin. Bonds, with his habit of jogging on batted balls and missing the cutoff man on throws from the outfield, was not the kind of player Martin preferred. Martin liked players who hustled at all times and paid attention to the fundamentals of the game.

The inevitable clash between player and manager occurred only two-and-a-half weeks later. During a series in Kansas City, Bonds failed to make a catch in right-center field, the misplay resulting in a triple for Al Cowens and leading to the go-ahead run for the Royals. Bonds was not charged with an error on the play, but Martin felt that the veteran outfielder did not give his best effort. Martin immediately removed Bonds from the game, replacing him with journeyman Rick Bladt. Bonds spent the rest of the day in the dugout; he and Martin glared at each other repeatedly.

In spite of the feud, Bonds put up a 30/30 season for the Yankees. He also impressed the Yankees by playing hurt, appearing in 145 games despite being hobbled by a torn ligament in his knee. Then, after the season, Bonds was charged with drunk driving. According to some observers, that incident cemented his fate in New York. General manager Gabe Paul, who had been a huge fan of Bonds, now felt committed to trading his star outfielder. He sent Bonds to the California Angels for a package of speedster Mickey Rivers and right-hander Ed Figueroa.

On the surface, this appeared to be a favorable career move for Bonds. Playing in Southern California, with a more laid-back fan base and a more forgiving media than what he had faced in New York, figured to help. The Angels also made him a full-time right fielder, where he was a more comfortable defender than in center field.

In contrast to his relationships with Billy Martin and Charlie Fox, Bonds now had a manager fully in his camp. “I consider Bobby Bonds one of the six best players in baseball,” Hall of Fame skipper Dick Williams informed The New York Times. “You don’t usually get a player of that quality in a trade, but we did.”

With his manager fully in his corner, the scenario for Bonds looked good. But then a preseason hand injury limited his effectiveness, grew worse as the season progressed, and eventually forced him to shut down his season in August. For the first time since his rookie season, he played in fewer than 100 games. Still, the Angels remained patient with Bonds, and watched him flourish in his second season with California. He drove in a career-high 115 runs, hit 37 home runs, stole 41 bases, and lifted his OPS to .862 in 1977.

Bonds and the Angels should have been a perfect long-term match. But there was the matter of baseball’s new free agent system, which had gone into effect after the 1976 season. Bonds had just one year left on his contract. Concerned that they might lose him to another team without any compensation, the Angels traded Bonds, outfielder Thad Bosley and pitcher Richard Dotson to the Chicago White Sox for a package of young catcher/outfielder Brian Downing and right-handers Chris Knapp and Dave Frost.

White Sox owner Bill Veeck loved the idea of having Bonds, the kind of supreme talent who could draw fans to Comiskey Park. Yet Veeck knew that he had no chance to sign Bonds to a multi-year contract. So when the White Sox played badly out of the gate in 1978 and quickly fell out of contention in the Western Division, Veeck cut bait and sent Bonds packing after only 26 games with the team. This time Bonds headed south, joining the Texas Rangers in exchange for two younger outfielders: Claudell Washington and Rusty Torres.

In contrast to the Angels and White Sox, the Rangers succeeded in signing Bonds to a long-term contract. But they soon regretted the decision, feeling Bonds was playing indifferently.

Not surprisingly, the Rangers traded Bonds that winter, sending him and young right-hander Len Barker to the Cleveland Indians for hard-throwing reliever Jim “The Emu” Kern and utility infielder Larvell “Sugar Bear” Blanks. As colorful as those players might have been, the return of Emu and Sugar Bear seemed awfully light for a player of Bonds’ enormous talents.

Bonds became a popular player in Cleveland, but his adviser and lawyer told him to take advantage of one of his contractual rights, which allowed him to demand a trade. That infuriated Gabe Paul, by now the president of the Indians. Paul accommodated Bonds by sending him to the Cardinals in a deal for right-hander John Denny and switch-hitting outfielder Jerry Mumphrey.

Although Bonds had generally gained favor with fans in Cleveland, he did not curry support with all of his teammates. Indians center fielder Rick Manning, who played alongside Bonds, offered a scathing commentary on Bonds during an interview in the spring of 1980. “He had his mind on [the game] only about 20 games a season,” Manning bluntly told the Sporting News. “I’d rather play with a guy who tries every game. Bobby wouldn’t hit the cutoff man if [the cutoff man] were King Kong.”

Manning’s negative assessment ran in contrast to the positive reviews that Bonds had received from his teammates over the years. Most of his teammates, whether in San Francisco or New York, had praised Bonds for his good his sense of humor and his willingness to help younger players.

In 1980, Bonds’ performance fell off drastically with the Cardinals. A hand injury suffered early in the season affected his hitting. Additionally, Bonds was now 34 and showing signs of slippage in the departments of power and speed. After a dismal season in St. Louis, the Redbirds released him, a stunning development for a player who had hit a combined 54 home runs over the two previous seasons. So by the time his 1981 Fleer card hit stores, Bonds was actually out of work, at least in terms of the major leagues. That same summer, Terry Cashman released his hit song, “Talkin’ Baseball,” which included the line, “and Bobby Bonds can play for everyone.”

One of Bonds’ many former teams, the Rangers, signed him to a minor league contract but never brought him back to the big leagues, instead selling him to the Chicago Cubs. Bonds played 45 games for the Cubs, hustling and playing hard throughout his time there, but his hitting skills had departed him. Convinced that Bonds was done, the Cubs gave him his release that October. When you’ve turned 35 and have been released twice, the signs are not favorable. Deciding to take a flyer on their former player, the Yankees signed him to a minor league contract and gave him a look at Triple-A Columbus in 1982, but he batted a weak .179. The Yankees released him, marking the end of his playing days.

The unceremonious finish to Bonds’ career, along with his many travels since his days in San Francisco, left his reputation tarnished. Fortunately, Bonds did something to correct the image. Having learned the game from people like Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, he passed those lessons on as a hitting coach, first with the Indians and then with the Giants. In the latter position, he worked directly with his son, Barry. Bonds was almost universally loved by the hitters that he worked with, both in Cleveland and San Francisco.

That reputation didn’t prevent him from being fired in 1996. Understandably, the decision angered his son, Barry. Then came the devastating news of 2002; Bonds was diagnosed with both a brain tumor and lung cancer. He then suffered a bout with pneumonia and had to undergo open heart surgery. In August of 2003, a gravely ill Bonds, sitting in a wheelchair, visited Pac Bell Park in San Francisco one final time to watch his son play. Three days later, Bobby Bonds died, at just 57 years old.

There’s a certain sadness that comes with remembering Bobby Bonds. The peak of his career did not last long enough for him to fulfill the predictions of all-time greatness. Similarly, his life was too short. Furthermore, Bonds died never having the chance to see his son break Hank Aaron’s all-time home run record. The sadness is only compounded by his 1981 Fleer card, where we see him, aging and forlorn, near the end of his fine career.

But then I remember the other side of Bonds, the young player who was so dynamic and forceful with the Giants. I recall a player who could go 30/30 in any season, a player who was just about the most exciting performer in the game. When Bonds played, you stopped for a moment to watch him.

That’s the Bobby Bonds that I prefer to remember.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

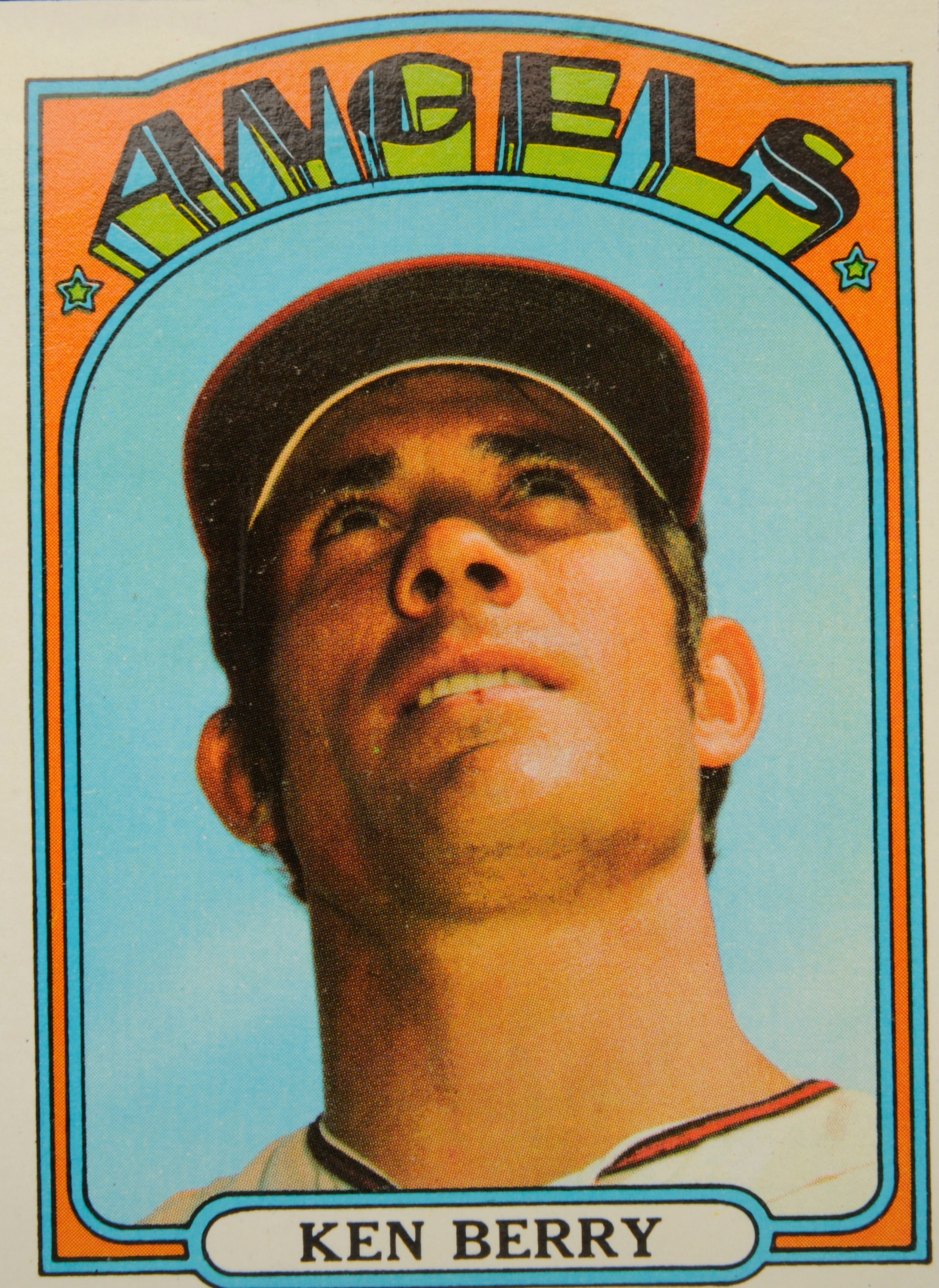

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

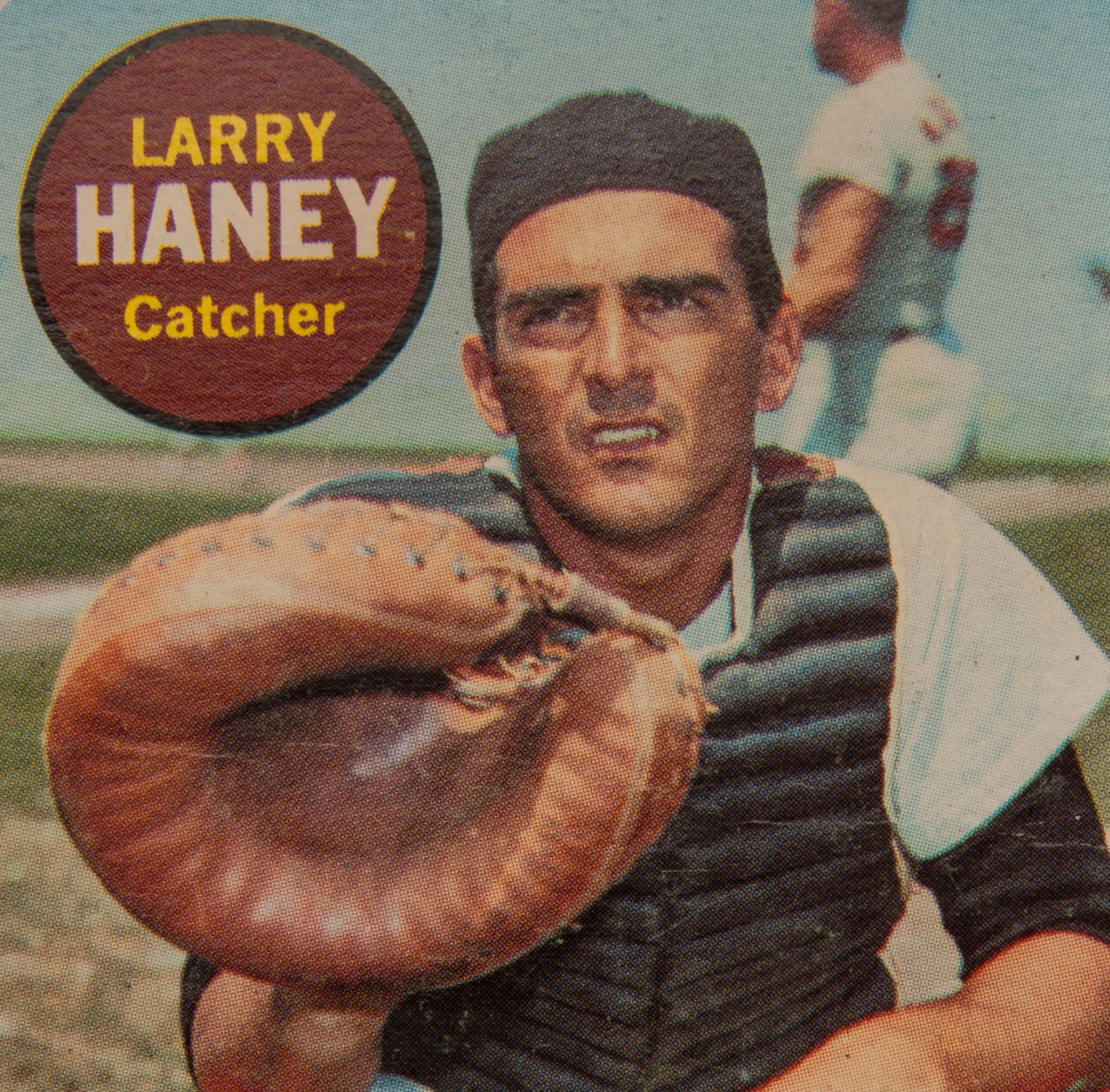

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Class of 2016 Reflects on Election

#Shortstops: Dave Winfield still towers over the game

Harold Baines debuts on Today’s Game Era ballot

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

#GoingDeep: Cristóbal Torriente Bests the Bambino

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

Ten Named to Today’s Game Era Ballot for National Baseball Hall of Fame Consideration

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

BA MSS 67, Folder 21, Corr_1957_1_11b

01.01.2023

Wendell Smith Chronology

01.01.2023

1985 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023