- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

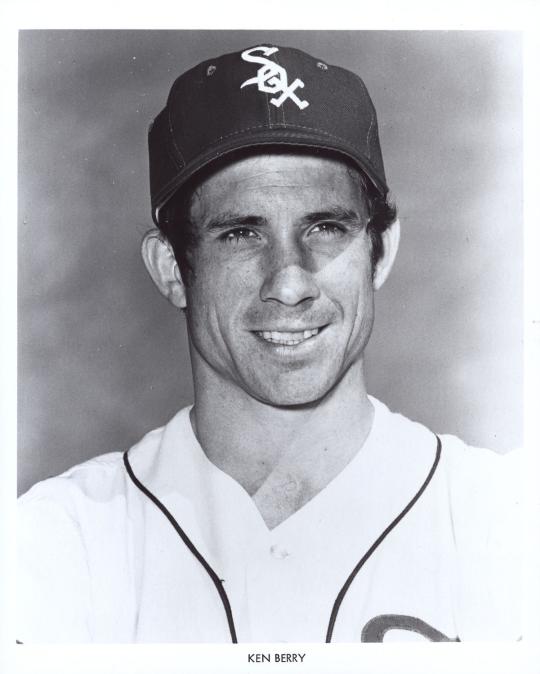

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Ken Berry’s 1972 Topps card gives us a glimpse into the popular culture of television from the era, along with what I like to call the power of the upturned cap. Let’s explain that latter point first. Back in the 1960s and 70s, Topps photographers sometimes asked players to turn their caps upward, or simply took pictures from such a low angle that the cap’s logo would be obscured from our view. This was no accident. By doing so, Topps protected itself against the possibility that a player would be traded during the winter. If that happened, Topps didn’t usually have time to acquire a photograph of the player in his new team’s uniform. By creating a bit of an illusion with the upturned cap, Topps took the team logo out of the equation, giving the player a generic look that could fit his new team.

The trick with this method was trying to predict which players might be traded during the time lapse. Superstars were not as likely to be dealt, leaving journeymen and middle-of-the-road players as the more likely subjects of upturned caps. Those alternate photographs turned out to be awfully handy for Topps in its efforts to stay current with its newest set of baseball cards.

One of those players on the move was Ken Berry, who was a very good defensive center fielder in his day, but was neither a household name nor a star. After the 1971 season, the Chicago White Sox traded Berry, sending him to the California Angels. Thankfully, Topps had already taken a photograph of Berry from a low angle, so that we can only see the green underside of his cap, and not the colors or the logo on the bill of the cap.

Berry’s 1972 Topps card also became a source of embarrassing confusion for me. When I first saw this card, I thought that Berry was the same Ken Berry who starred in the 1960s television series, F Troop. Keep in mind that I was all of seven at the time, and not really able to distinguish that two relatively famous people might share the same name. Beyond that, the very capable comic actor who portrayed Captain Wilton Parmenter, the not-so-fearless leader of the mythical Fort Courage, seemed young enough to be a ballplayer.

Additionally, F Troop aired during the fall and winter months, so I thought there would be little conflict with the baseball season. I had no idea that TV series started filming during the summer months, which would have made it difficult for Berry the baseball player to honor his major league schedule with the Angels. To make matters more embarrassing, I didn’t realize that F Troop had aired live from 1965 to 1967, and was only being shown in reruns in 1972.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

All of this confusion could have been cleared up if I simply had taken a closer look at Berry’s 1972 card, which provides a good close-up of his face. He looks nothing like the actor Ken Berry, who at the time had a much narrower face and a thinner nose. But then again, when you’re all of seven years old, it’s hard to notice these things.

In an alternate world, Captain Parmenter would have made a good outfielder, just like baseball’s version of Ken Berry. Baseball’s Berry won two Gold Glove Awards for his defensive play in center field and earned selection to the 1967 All-Star Game. In 1960s parlance, he was often referred to as an “excellent flychaser.” As the overmatched commander of F Troop, Parmenter looked lean and fit, and appeared to have enough speed to play center field. Some of the other characters on F Troop also fit the stereotypes of ballplayers. Sergeant Morgan O’Rourke, played so smoothly by veteran actor Forrest Tucker, would have made a strapping, left-handed hitting first baseman.

Corporal Randolph Agarn, as played by the clownish character actor Larry Storch, would have fit right in as a goofy, wisecracking utility infielder. And then there was Hannibal Dobbs, portrayed by another notable character actor of the era, James Hampton, who gained fame for his wonderful depiction of “Caretaker” in the football film, The Longest Yard. Hannibal Dobbs would have seemed just right as a slightly daffy relief pitcher.

With or without baseball, F Troop was a solidly good, funny show that sometimes reached high points of hilarity. It never would have flown in today’s world of politically correct speech, mostly because of the portrayal of the Native Americans on the show. F Troop also had likeable and sympathetic characters, even if some of them were a bit mischievous. It just would have been that much better if the same Ken Berry who played center field so skillfully for the Angels, White Sox, Cleveland Indians, and Milwaukee Brewers had been the same guy who so cleverly portrayed Captain Parmenter on TV.

The real version of Ken Berry (the baseball player, that is) started his professional career with the White Sox’ organization in 1961. Rushed to the major leagues just one year later, he made brief cameos with Chicago over the next three seasons before being brought to the major leagues for good in 1965. Installed as the White Sox’ starting center fielder, he hit a meager .218 with only 28 walks, but did hit 12 home runs and showed flashes of brilliance as a center fielder.

As well as Berry played center, he moved to left field in 1966, ostensibly to make room for a younger center fielder in Tommie Agee. Berry showed offensive improvement, lifting his batting average to .271 and his on-base percentage to .316. More importantly, Berry and Agree provided the White Sox with blanket coverage in the outfield, running down just about everything hit in the direction of left and center fields.

Berry impressed scouts not only with his jumps and his range, but his willingness to crash into outfield walls and barrier. On one occasion, he smashed into a wall, broke his sunglasses, and had to pick 25 pieces of glass out of his body and face. At other times, he injured his hands, wrists, and shoulders, all while tangling with outfield walls.

In 1967, the White Sox switched Berry yet again, this time shifting him to right field. A hot first half of the season, which saw Berry’s batting average rise to .309, coupled with injuries to perennial All-Stars like Al Kaline and Frank Robinson, earned him an All-Star Game selection. But a second-half slump reduced his average to .241 and his OPS to .640, making him an offensive liability during the dog days of the season.

By 1968, Berry was back in center field, largely because of the White Sox’ decision to trade Agree to the New York Mets as part of a deal for veteran outfielder Tommy Davis. Berry would remain in center field for three seasons, culminating in a career year in 1970. That’s when he batted a career-high .276, drew a personal best 43 walks, and won his first Gold Glove Award.

In particular, Berry’s fielding drew raves, especially from his grateful pitchers. One teammate called Berry the elite among center fielders. “Best I’ve ever seen,” said Sox left-hander Gerry Arrigo. “And I mean No. 1. And I’m including Curt Flood and Bobby Tolan.” Arrigo also took note of Berry’s knack for making leaping catches at the fence. “I mean, this guy’s fantastic. He jumps over fences, over walls, over everything.” One year, while playing for the White Sox, Berry caught five potential home runs balls while reaching over the fence at Comiskey Park. Berry became so adept at robbing home runs that he earned the nickname “Bandit.”

Berry’s 1970 performance put him at the peak of his career, but the situation also created a dilemma for the White Sox. Should they keep Berry, or consider trading him, given that his trade value was unlikely to soar any higher? The Sox chose the latter option, making him the centerpiece of a major trade with the Angels. The Sox sent Berry and two lesser players to California for outfielder Jay Johnstone, catcher Tom Egan, and right-hander Tom Bradley, necessitating the use of the alternate Topps photograph.

Berry’s first year with California did not go well, at least not with the bat in his hand. He slumped to a .221 batting average, hit only three home runs, and put up an OPS of .578. But he did yeoman’s work in the field, where the Angels asked him to man center fielder in between the stone-gloved duo of Alex Johnson and Tony Conigliaro. Neither Johnson nor Tony C. offered much in terms or range, forcing Berry to cover much of the ground from alley to alley.

Offensively, Berry bounced back in 1972, hitting .289 with an OPS of .723, and winning his second Gold Glove Award. He put up another solid year in 1973, but the Angels, concerned about his diminishing range in the field, traded him to Milwaukee that winter as part of a multi-player deal for outfielders Downtown Ollie Brown and Joe Lahoud. From there, Berry finished out his career as a backup with the Brewers and Indians, who released him in June of 1975.

With his playing days over, Berry pursued a career as a minor league manager and coach. He also dabbed, however briefly, in Hollywood. Hired as a consultant for the movie, Eight Men Out, Berry also picked up a small speaking role as a fan who heckles Shoeless Joe Jackson. While it didn’t provide the steady work of F Troop, it did give him a few moments of on-screen glory.

A few years back, when Berry was working as a coach for a New York Mets farm team, I had the chance to meet him at Damaschke Field in Oneonta. We talked about some of the differences in the game between now and when he played. Coming across as cordial and sincere, Berry mentioned that the availability of video today, and the level of instruction given to hitters nowadays, as some of the biggest changes that he had witnessed during his five decades in the game.

Now retired from coaching, Berry has ventured into the area of book publishing. He has written two children’s books: Artie the Awesome Apple and Clyde the Clumsy Camel. It seems that Ken Berry is doing more and more to distinguish himself from the man who once made Captain Parmenter a household name.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

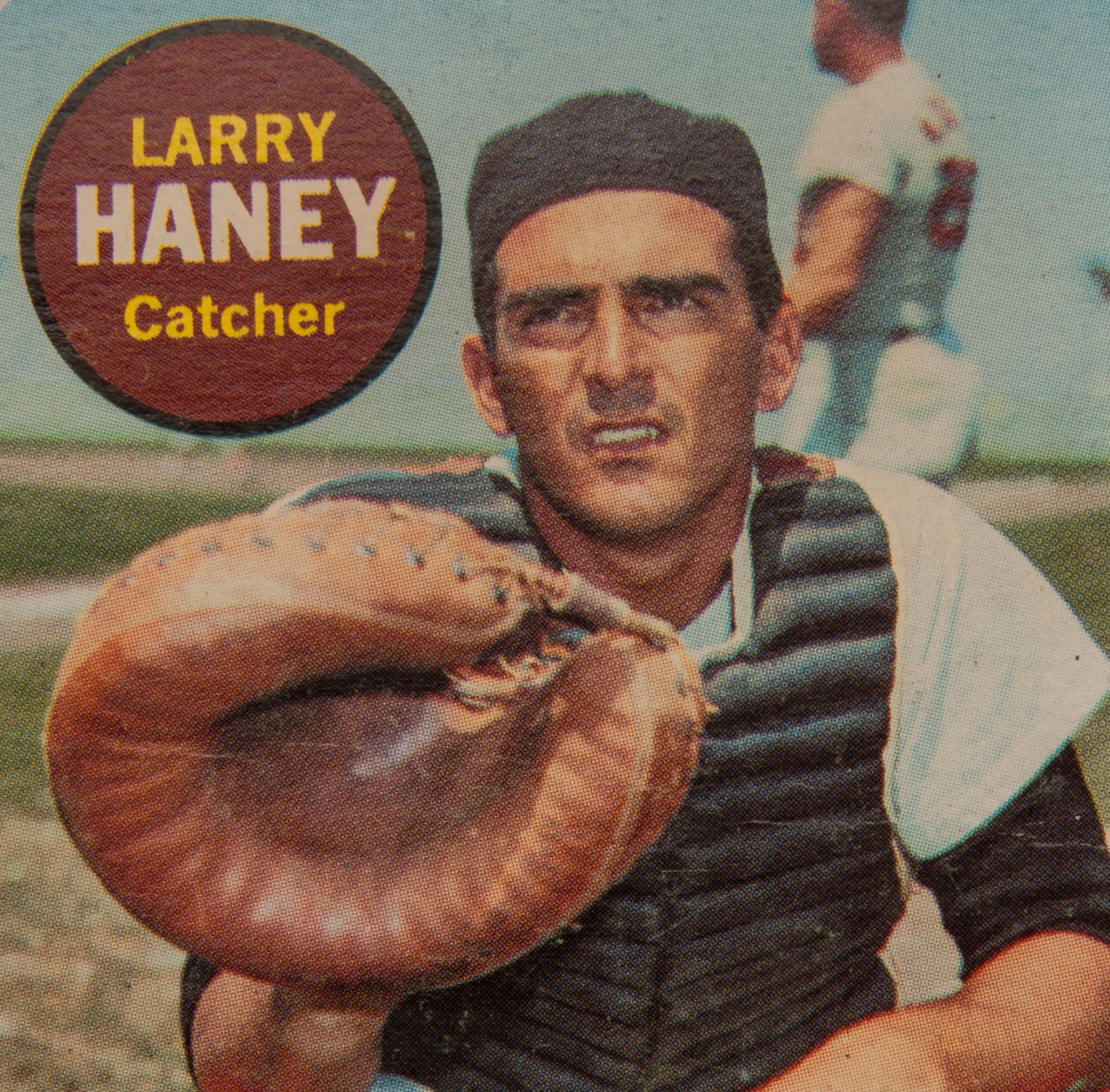

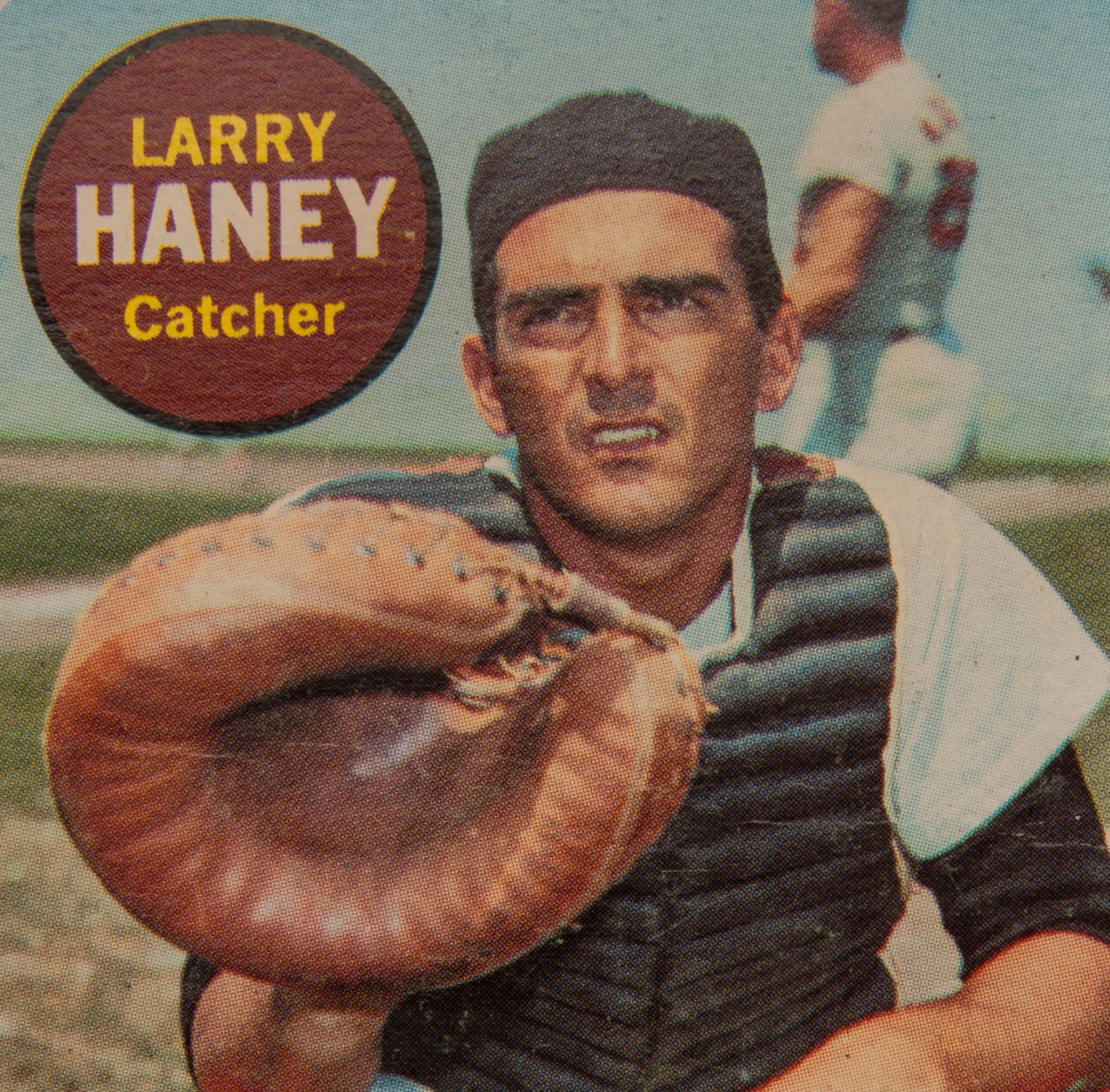

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

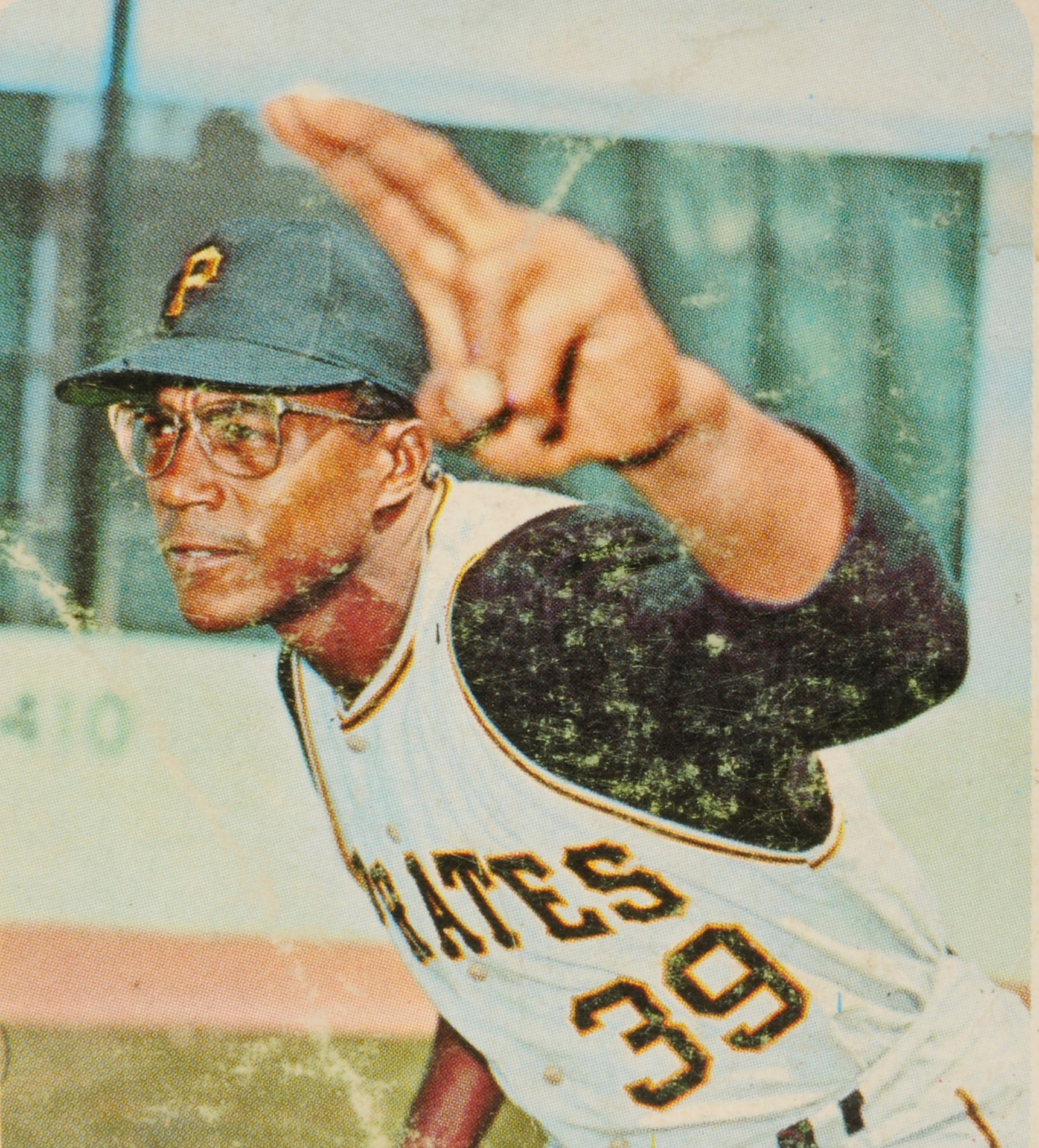

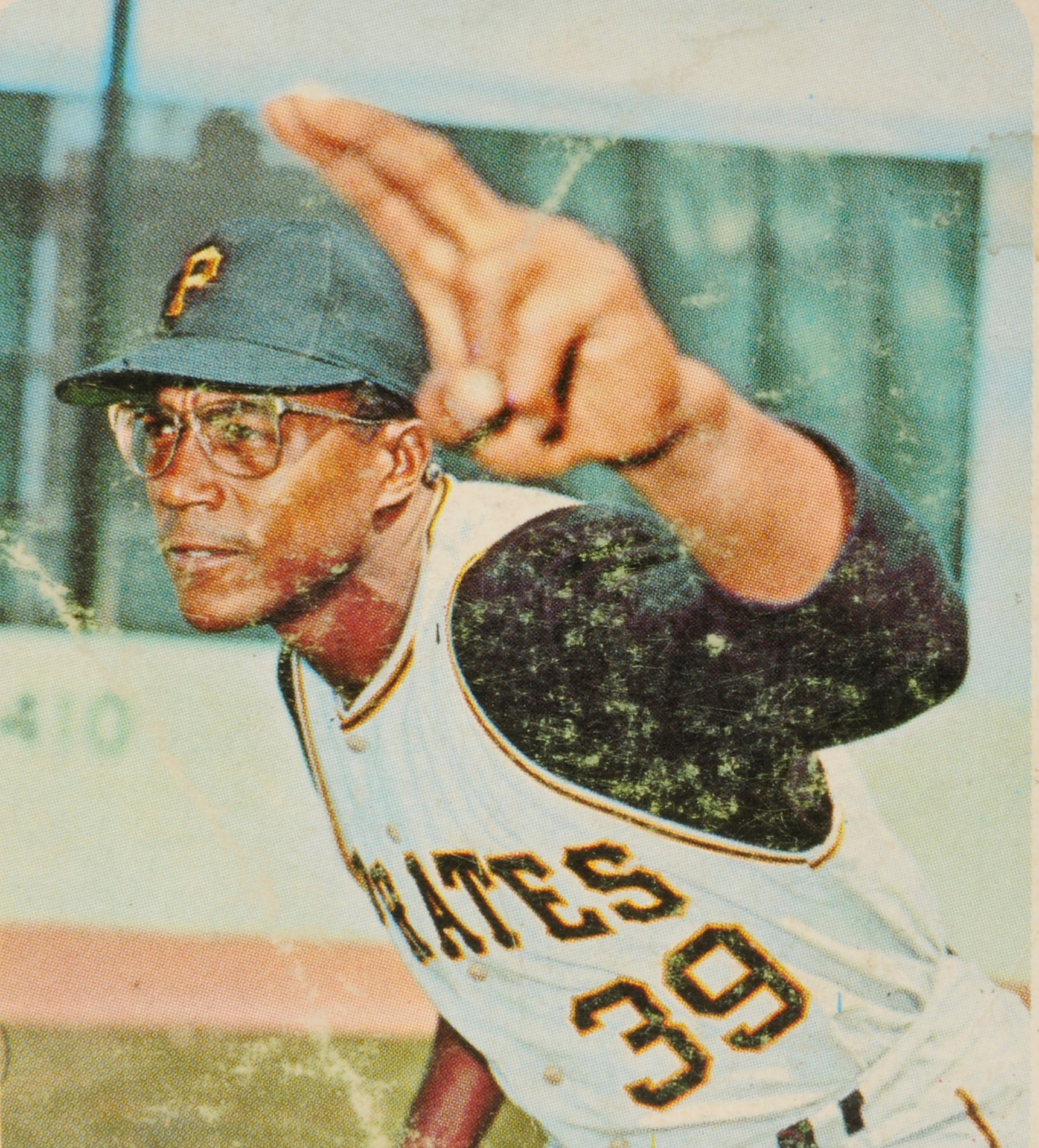

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Veale

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Veale

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ken Berry

Unforgettable: Four Newest Hall of Famers Inducted

Historic crowd cheers Griffey, Piazza into Hall of Fame

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr_1972_08_09

Wade Boggs, Ryne Sandberg elected to Hall of Fame by BBWAA

Legends, SIMPSONS Team Up for Memorable Hall of Classic

History Book

'Fastball' Headlines Tenth Annual Baseball Film Festival

March Matinee: Meet Hoops Heroes Who Call Cooperstown Home

01.01.2023

All-Stars Abound Memorial Day Weekend at Baseball Hall of Fame Classic

01.01.2023