- Home

- Our Stories

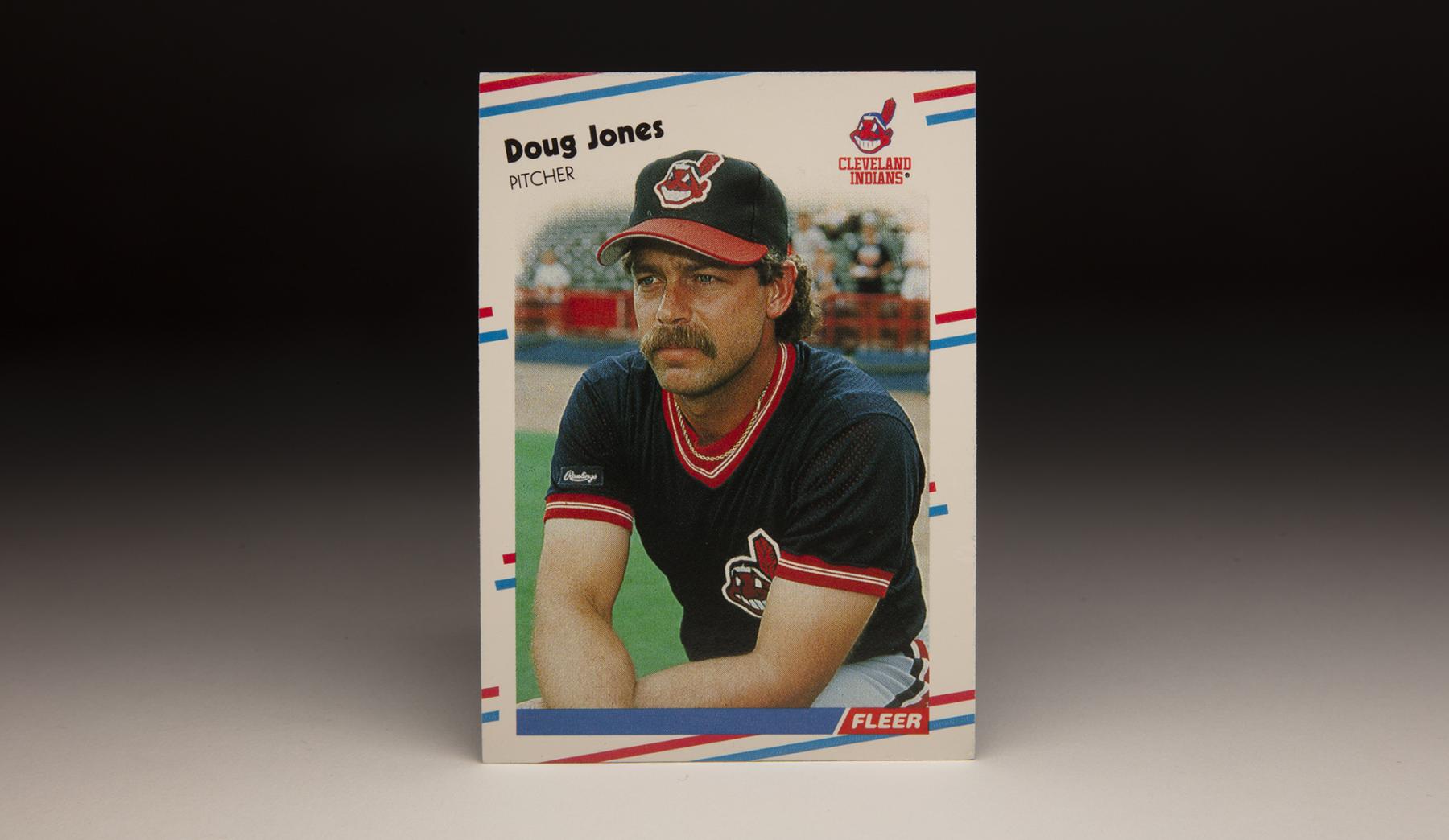

- #CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Doug Jones

#CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Doug Jones

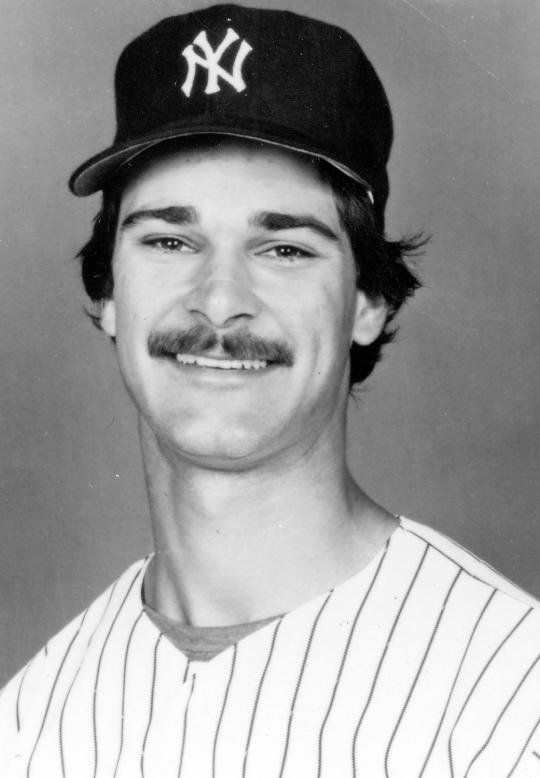

Doug Jones didn’t earn a regular big league roster spot until the season he turned 30 years old.

A two-pitch pitcher with an 84-mile per hour fastball, Jones then spent much of his 30s toiling for an Indians team that was a few seasons from being rebuilt into a winner.

It hardly seemed to be a recipe for success. And yet Doug Jones saved 303 big league games, becoming just the 11th pitcher to reach the 300-save mark.

It was a lesson in the fundamentals of pitching that left batters flailing at changeup after changeup.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Born June 24, 1957, in Covina, Calif., Jones and his family soon moved to Lebanon, Ind. After starring on the mound in high school, Jones enrolled at Butler University in Indianapolis before transferring to Central Arizona College.

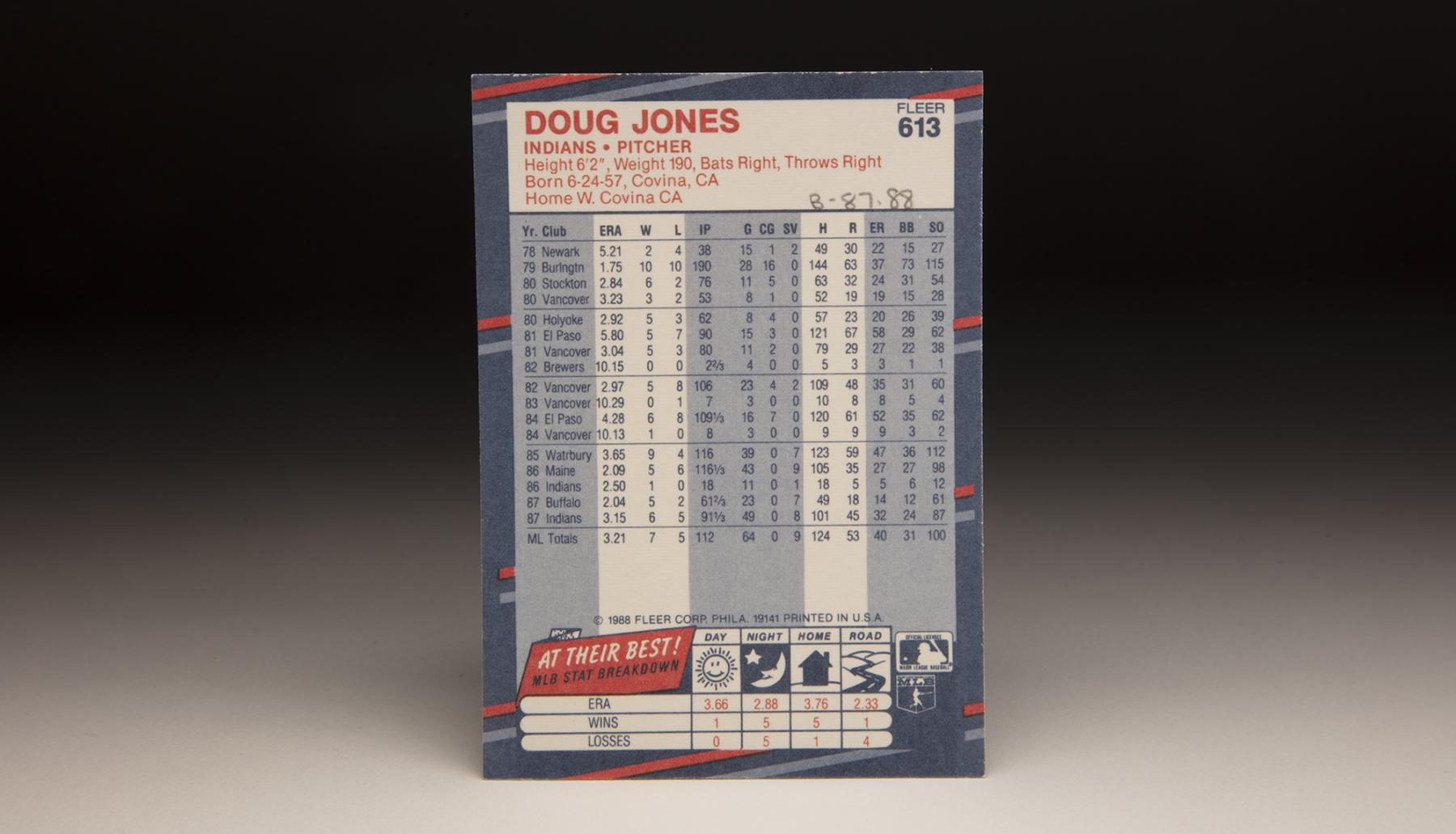

In 1978, the Brewers took Jones with a third round pick in the January MLB Draft. From there, Jones embarked on a five-year journey through the minor leagues – mostly as a starter. He dominated Midwest League batters at Class A Burlington in 1979, going 10-10 with a 1.75 ERA in 190 innings.

Jones was 14-7 with a 2.97 ERA over three leagues in 1980, climbing all the way to Triple-A Vancouver. But Jones was sent back to Double-A El Paso in 1981 and struggled, receiving a recall to Vancouver in July only because of a string of injuries. He got back on track in Triple-A, finishing the season with a 5-3 record and 3.04 ERA in 10 starts for the Canadians.

Jones made the Brewers’ Opening Day roster in 1982, debuting in the big leagues in the first game of the season with one scoreless inning in relief in Milwaukee’s 15-4 win over Toronto. But after allowing two singles over the span of three batters against the Rangers on April 18, Jones was sent back to Vancouver, where he went 5-8 with a 2.97 ERA as a spot starter and reliever.

Then, after appearing in only three games with the Canadians in 1983 due to a muscle injury in his pitching shoulder and going 7-8 with a 4.68 ERA in Double-A and Triple-A in 1984, Jones became a minor league free agent and left the only pro organization he had ever known.

He surfaced with the Indians near the end of Spring Training in 1985, paying his own expenses while showing the Indians a new changeup that resembled a palm ball. The Indians sent the 27-year-old Jones to Double-A Waterbury and put him in the bullpen, where he went 9-4 with a 3.65 ERA.

At one point during the season, the Indians asked Jones to become a pitching coach.

“I was a little flattered,” Jones said. “But at the same time it threw me off. I thought I could pitch in the big leagues.”

In 1986, Jones was 5-6 with a 2.09 ERA almost for the Triple-A Maine Guides of the International League, working almost exclusively in relief. He made 11 appearances with the Indians as a September call-up, going 1-0 with a save and a 2.50 ERA.

“We probably should have called him up sooner,” said Indians manager Pat Corrales.

Jones went to pitch in Puerto Rico after the season and was named the Puerto Rican League’s Relief Pitcher of the Year. After dazzling the Indians in Spring Training of 1987 – posting a 1.23 ERA in 14.2 innings – Jones won a spot in Cleveland’s bullpen.

“All I want,” Jones told the Willoughby, Ohio, News-Herald, “is to play this game for a few more years and make some money.”

After a rough start to 1987 that saw him sent back to Triple-A in April – he was 5-2 with an International League-leading 2.04 ERA in 23 games with the Buffalo Bisons – Jones was recalled on June 28. From that point, he went 6-4 with eight saves and a 2.68 ERA in 42 games.

“I was just pressing in April,” Jones told the Akron Beacon Journal upon his recall to Cleveland. “Every game was like the seventh game of the World Series to me. I was trying to do more than I was capable of doing.”

Jones struggled in Spring Training of 1988, however, while working on a cutter that he eventually abandoned. Indians manager Doc Edwards installed Chris Codiroli as the team’s closer to open the season, but turned to Jones in mid-April.

Aside from a one-inning stint on May 1 against the Athletics where he allowed six runs, Jones allowed just one earned run in the season’s first three months.

“When they were looking for a short man, I knew I could do the job,” Jones told the Kansas City Star. “All I wanted was to get some innings.”

On June 22, 1988, Jones tied the big league record with 13 saves in as many appearances when he locked down Cleveland’s 3-1 win over the Red Sox.

“I guess they keep records for everything,” Jones told the Associated Press. “I had no idea about it until I read it a week or two ago.”

Jones extended the record to 15 before working three innings in a July 4 game the Indians ultimately lost to Oakland in 16 innings.

By the end of the season, Jones had posted a franchise-record 37 saves to go with a 3-4 record and 2.27 ERA in 51 games. He earned the first of five career All-Star Game selections that year and finished 15th in the American League Most Valuable Player voting.

“He’s a guy who has the capability of throwing a change-up in a fastball situation and make a tough pitch,” Yankees All-Star Don Mattingly told the Kansas City Star. “That also sets up his pitches better. There’s a big difference between the fastball and the palm ball or whatever it is he has.”

During the next two seasons, Jones produced practically the same numbers as 1988. He was 7-10 with a 2.34 ERA and 32 saves in 1989, then went 5-5 with a 2.56 ERA in 1990 – breaking his own club record with 43 saves.

“I change speeds on both of them, but that’s all I throw,” Jones said. “My game is to get batters to hit the ball to someone. If I walk people or give up a home run, I’d be gone in a minute because I don’t have anything else going for me.”

In 1991, Jones proved to be a prophet. For the first time since 1987, he struggled to get hitters out – blowing three saves and losing three decisions by May 7. Saddled with a 1-7 record and 7.47 ERA in late July, Jones – a three-time All-Star who had agreed to a $2.05 million salary for 1991 – was sent to Triple-A Colorado Springs.

When he returned to the Indians as a September call-up, Cleveland made him a starter. He responded with wins in each of his first three outings – the first three starts of his big league career – and notched a save in the season’s next-to-last game, finishing the year with a 4-8 record, seven saves and a 5.54 ERA.

Following the season, the Indians chose not to tender a contract to Jones, making him a free agent. It was the start of a rebuild that would make Cleveland one of the best teams in baseball – and the beginning of a career rebirth for Jones, who signed with the Houston Astros on a minor league deal on Jan. 24, 1992.

“We’re going to make sure Doug has ample opportunity to pitch,” Astros general manager Bill Wood told the Atlanta Constitution.

Wood was true to his word as Jones appeared in a career-high 80 games and finished a big league-best 70 of them, going 11-8 with 36 saves and a 1.85 ERA. But the NL punched back in 1993 as Jones went 4-10 with 26 saves and a 4.54 ERA. Following the season, the Astros traded Jones and Jeff Juden to the Phillies for Mitch Williams.

A little more than a month before, Williams had surrendered a World Series-winning home run to Toronto’s Joe Carter.

“I’m not saying Doug Jones is going to be our closer,” Phillies manager Jim Fregosi told the Courier-Post of Camden, N.J. “He’s going to have to earn that.”

In typical Jones fashion, he did – going 2-4 with a 2.17 ERA and 27 saves in 47 games in that strike-shortened season. His contract expired that fall, and Jones quickly signed with the Orioles – a one-year deal with $1 million plus reachable incentives – when the strike was resolved in April.

“Every year, it seems I’ve got to come in (to Spring Training) and make people shake their heads and say: ‘Maybe he’s got something,’” Jones said. “For me, every time I pitch counts.”

Jones, who turned 38 in 1995, was 0-4 with a 5.01 ERA and 22 saves in 52 games. He signed on with the Cubs to start the 1996 season, struggled to a 2-2 record and 5.01 ERA and was released on June 15. But two weeks later, the Brewers brought Jones back to Milwaukee – where he was 5-0 with a 3.41 ERA in 24 games as a set-up man.

Then in 1997, Jones had perhaps his best year in the big leagues, going 6-6 with a 2.02 ERA and 36 saves over 75 games, leading all big league pitchers with 73 games finished. He struck out 82 over 80.1 innings, walking just nine and finishing 20th in the National League Most Valuable Player voting.

Taking over the closer’s job in April when Mike Fetters was injured, Jones blew only two save chances all season and was named the team’s Most Valuable Player.

Jones could not duplicate his success the next season, however, and was traded back to Cleveland on July 23, 1998, in a deal for Eric Plunk. The Indians were now an American League powerhouse, and Jones performed admirably as a set-up man – going 1-2 with a 3.45 ERA in 23 games. The Indians won the AL Central title and afforded Jones his first chance to pitch in the postseason when he pitched in Game 1 of the ALDS vs. the Red Sox.

Once again a free agent following Cleveland’s loss to the Yankees in the ALCS, Jones signed with Oakland – where he went 5-5 with 10 saves and a 3.55 ERA in 70 games and recorded his 300th career save on Sept. 11, 1999. He reprised his role as a set-up man in 2000 in his final big league season with a 4-2 record and 3.93 ERA in 54 games, working two scoreless outings against the Yankees in the ALDS.

Jones finished his career with a record of 69-79 and a 3.30 ERA over 846 games. All but one of his 303 career saves came after he turned 30 years old.

On the all-time list of two-pitch pitchers with sub-90 mph fastballs, not many had more success than Doug Jones.

“I’ve seen a lot of guys with more talent than me who didn’t make it throw their hands up in the air and walk away from the game,” Jones said in 1987. “And once or twice in my career, I’ve felt like quitting. But what would that prove? Only that I didn’t have the fortitude to stay with it.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

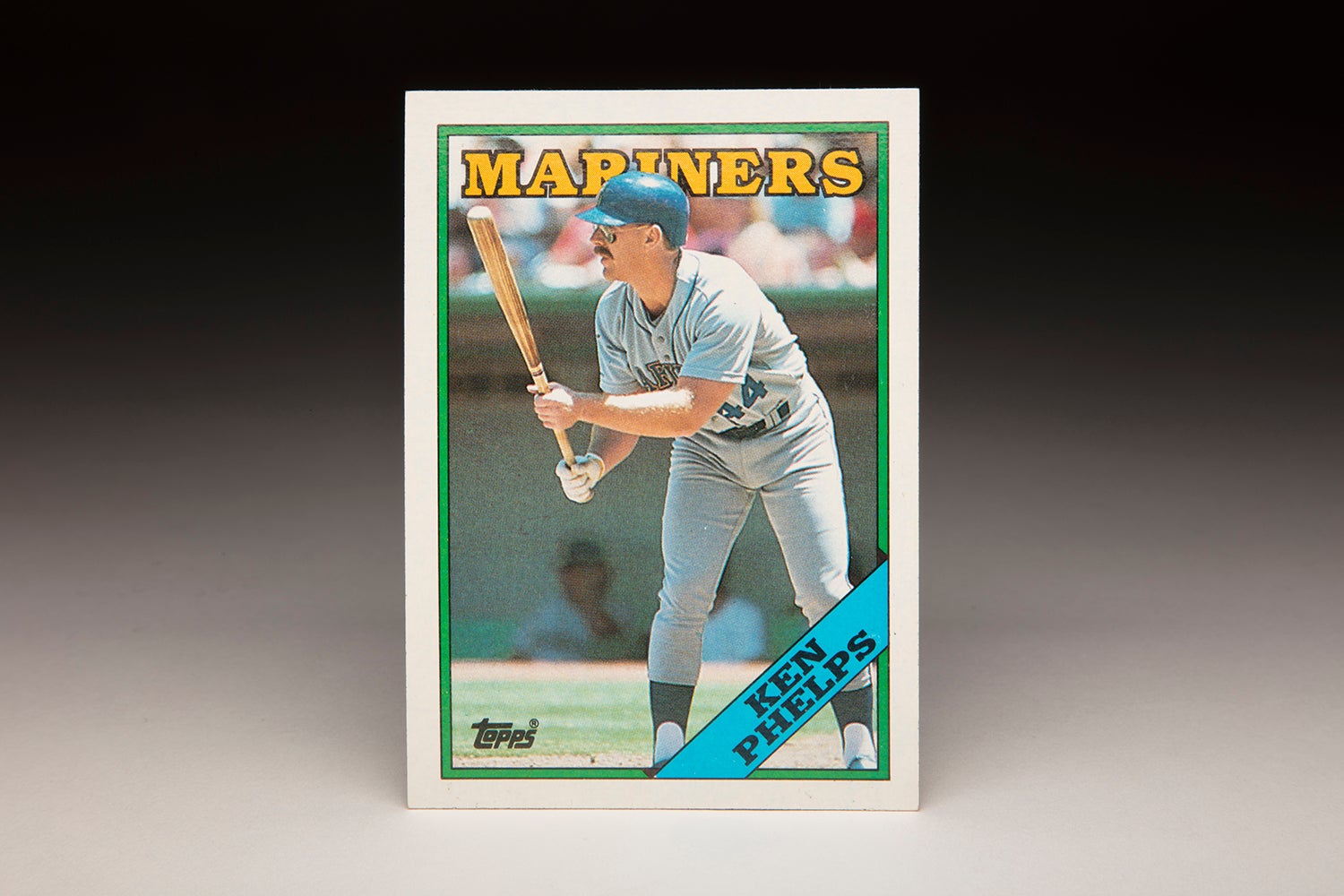

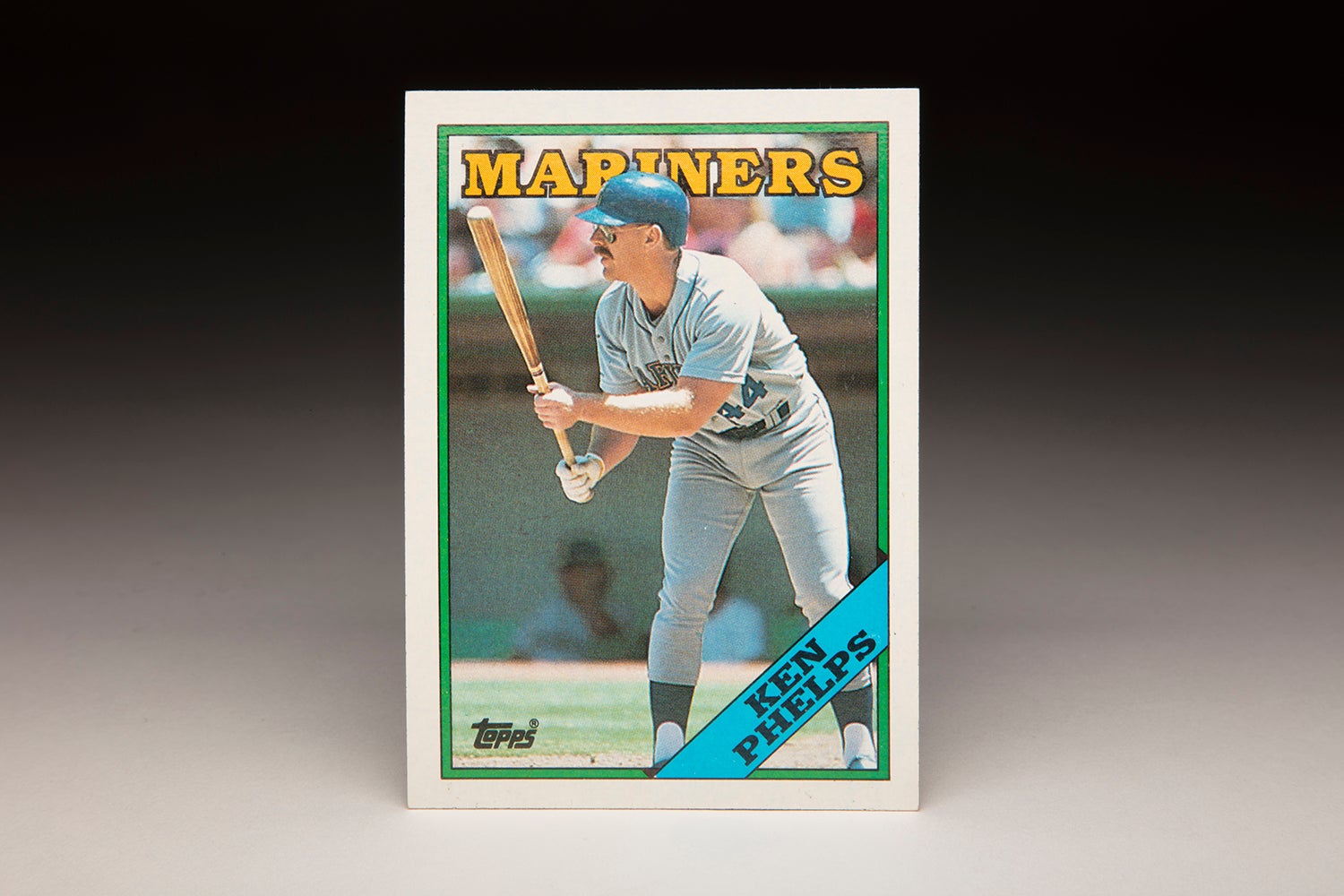

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

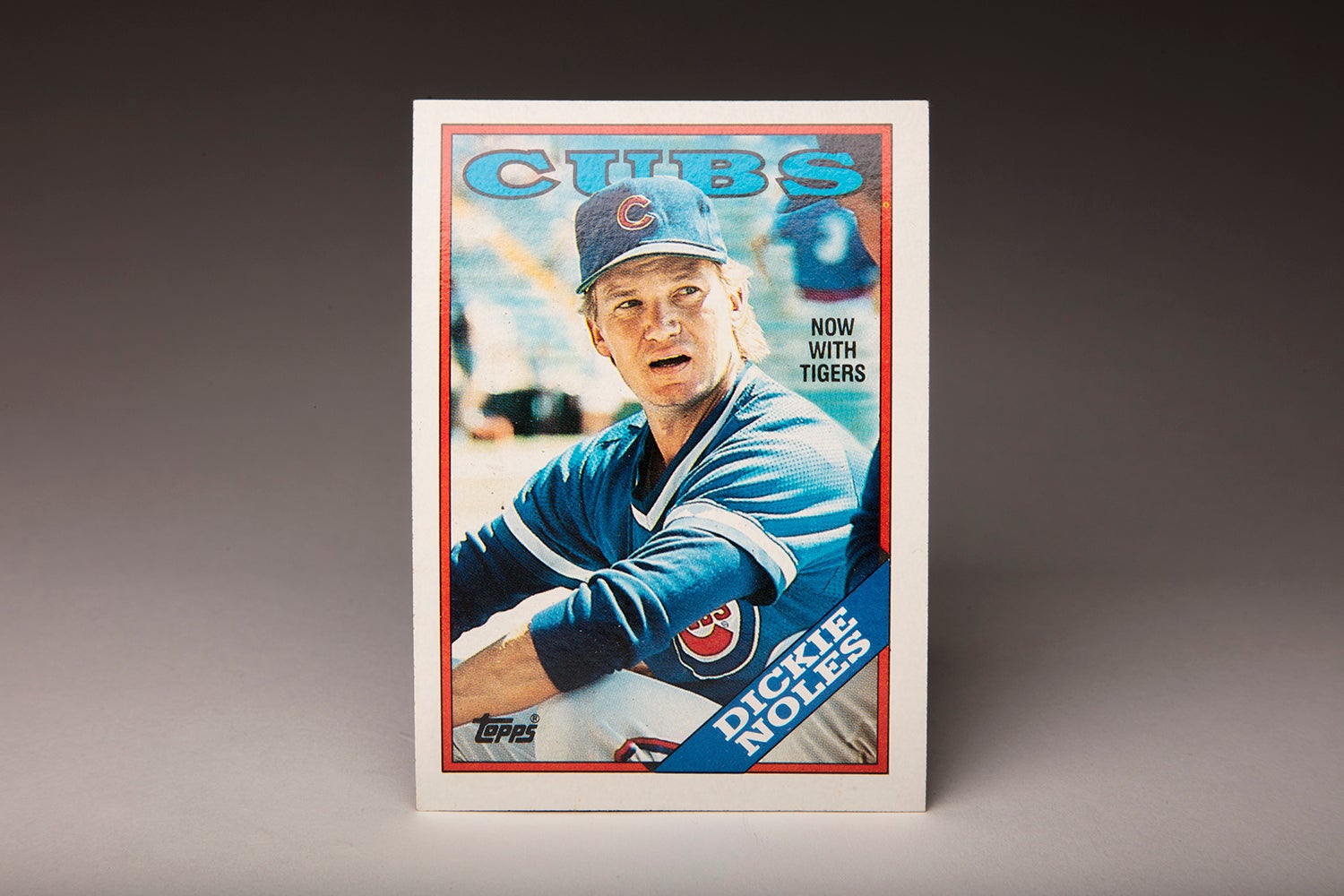

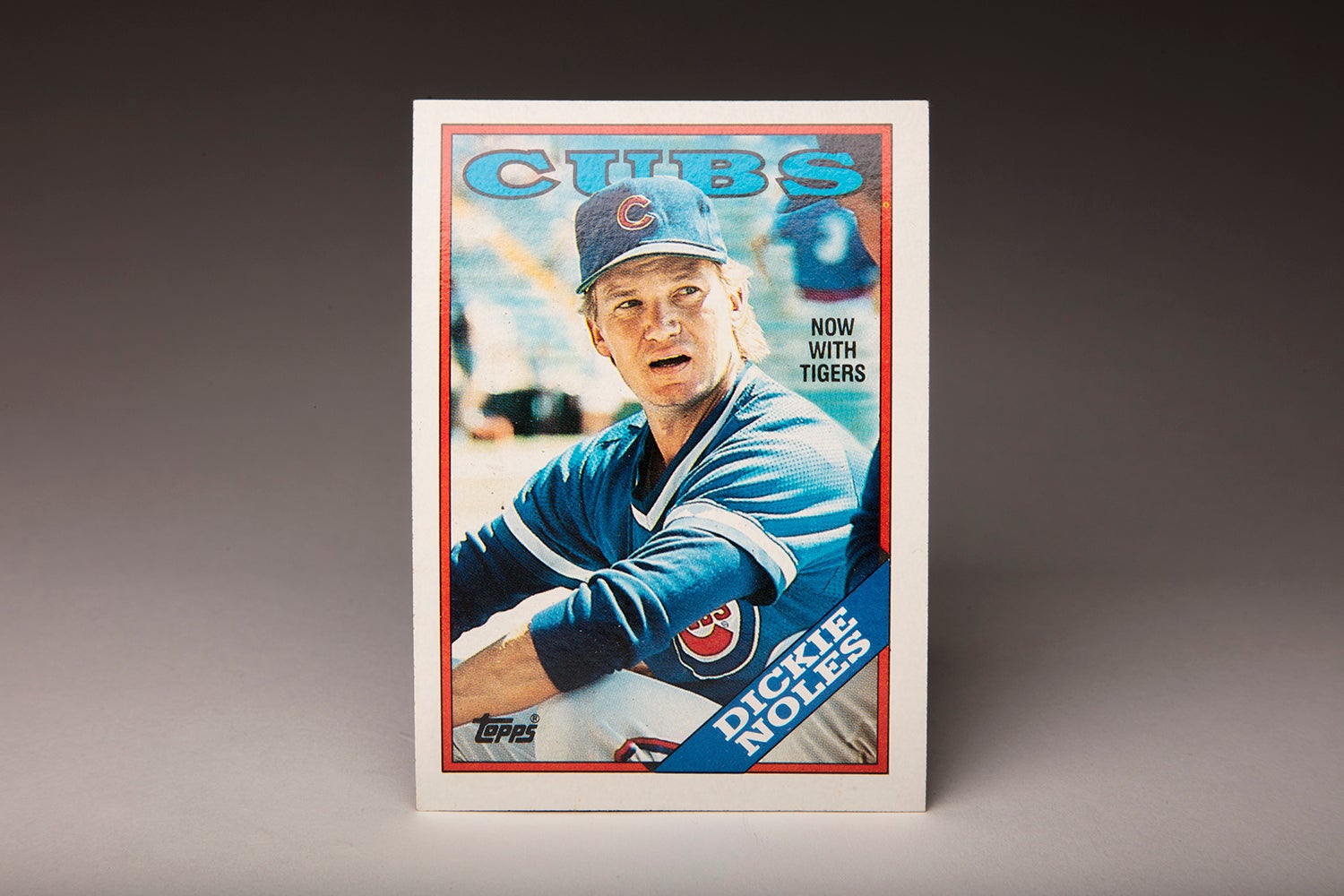

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

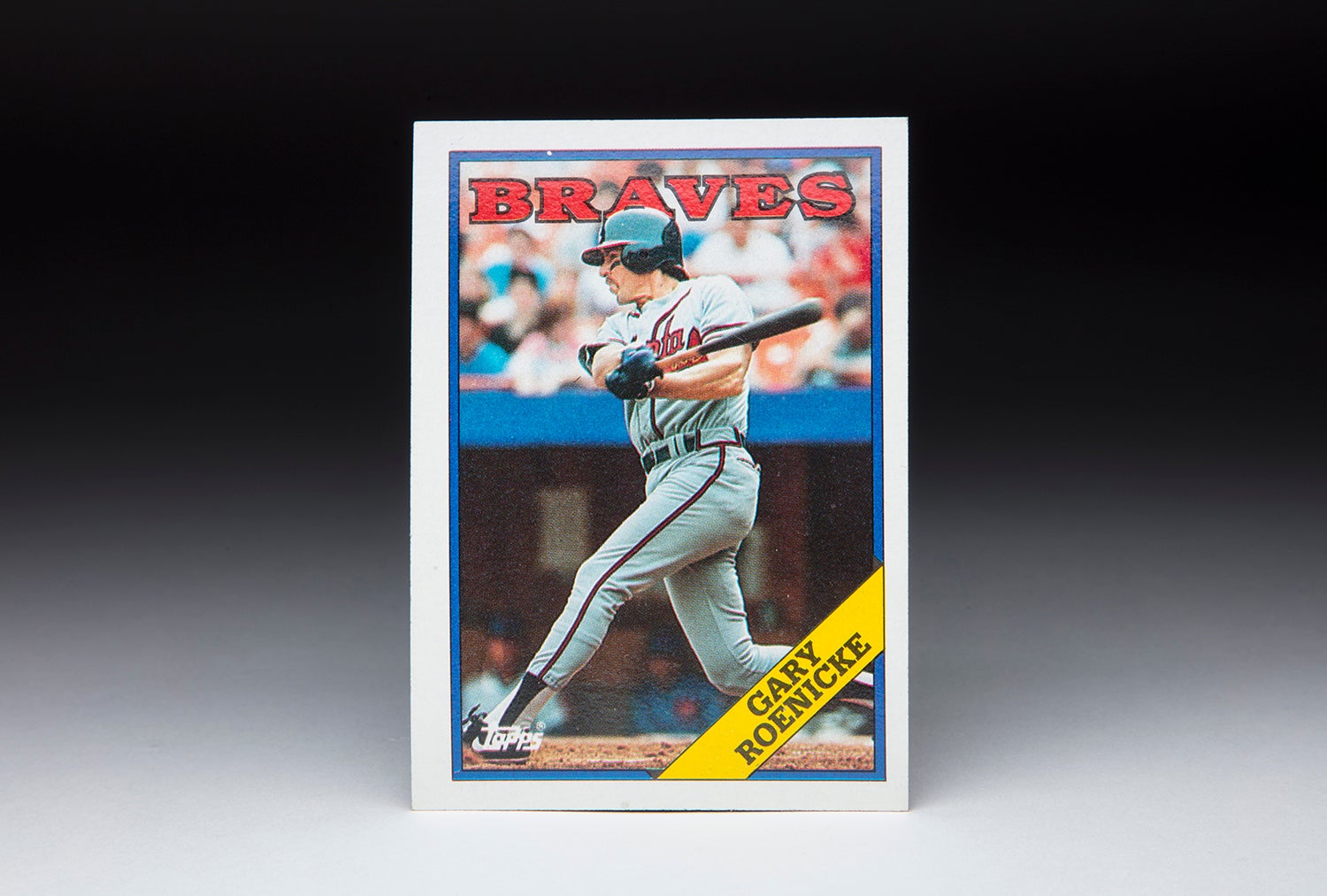

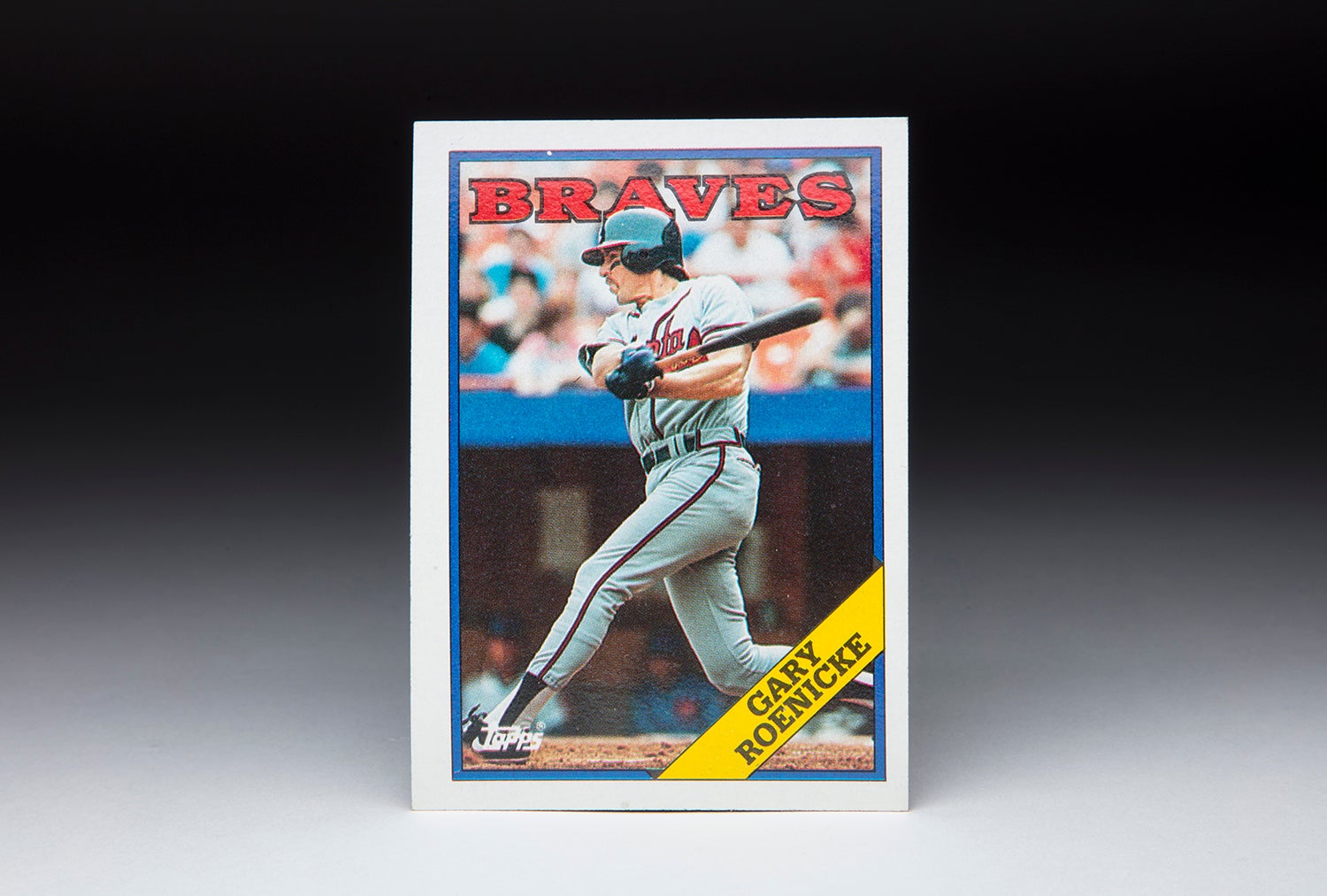

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

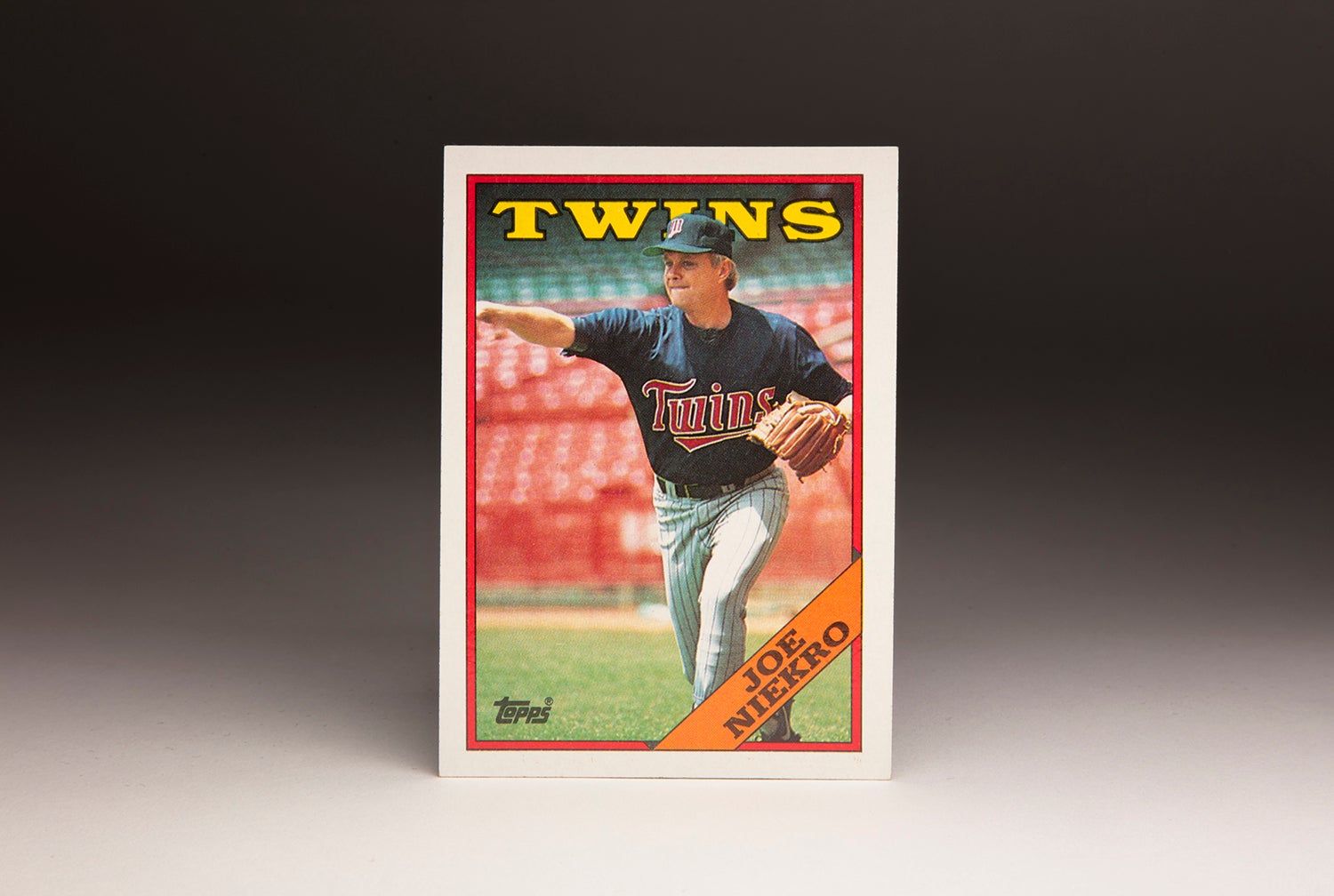

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Joe Niekro

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke