- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The platoon player has become nearly extinct. At one time, as recently as the 1970s and 80s, platoon players performed a major role on each team’s 25-man roster.

In the absence of one very good player being able to handle a position, teams sometimes turned to two lesser players, one a left-handed hitter and one a righty, to fill the void. Typically, the manager would use the left-handed hitter against right-handed pitching, and the right-handed hitter against left-handed pitching. Oftentimes, this turned out to be a beautiful arrangement.

For the most part, platoon players have tumbled into oblivion. With big league teams feeling the need to carry 12 or 13 pitchers, that has reduced the available number of position players. Most teams simply don’t have room for players who can start only half of the time. They want fulltime starting players and a few backups who can cover a lot of positions. Versatility has become more important than having a player who absolutely tears apart pitching from one side of the mound.

Recently the baseball world lost one of its greatest platoon players when Oscar Gamble, once profiled in CardCorner, died after a lengthy battle with cancer. Considered vulnerable against lefty pitching, Gamble usually found his way into the lineup against right-handers, sometimes in the outfield and sometimes as a DH. Gamble usually hammered right-handed pitching, hitting for power while reaching base at an above-average clip.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

One of Gamble’s contemporaries was Gary Roenicke, pronounced “renn-uh-kee.” Unlike Gamble, Roenicke batted from the right side of the plate. Like Gamble, he had his way with pitchers of the opposite hand, in this case left-handed pitching. Over the span of several years, Roenicke and fellow outfielder John Lowenstein formed the game’s most famous – and arguably best – platoon arrangement. In splitting time as the left fielders for the Baltimore Orioles, Roenicke and Lowenstein gave their managers optimal production from the position. In some seasons, their combined statistics rated equally with those of a star left fielder. That’s how good the firm of Roenicke and Lowenstein was at its peak.

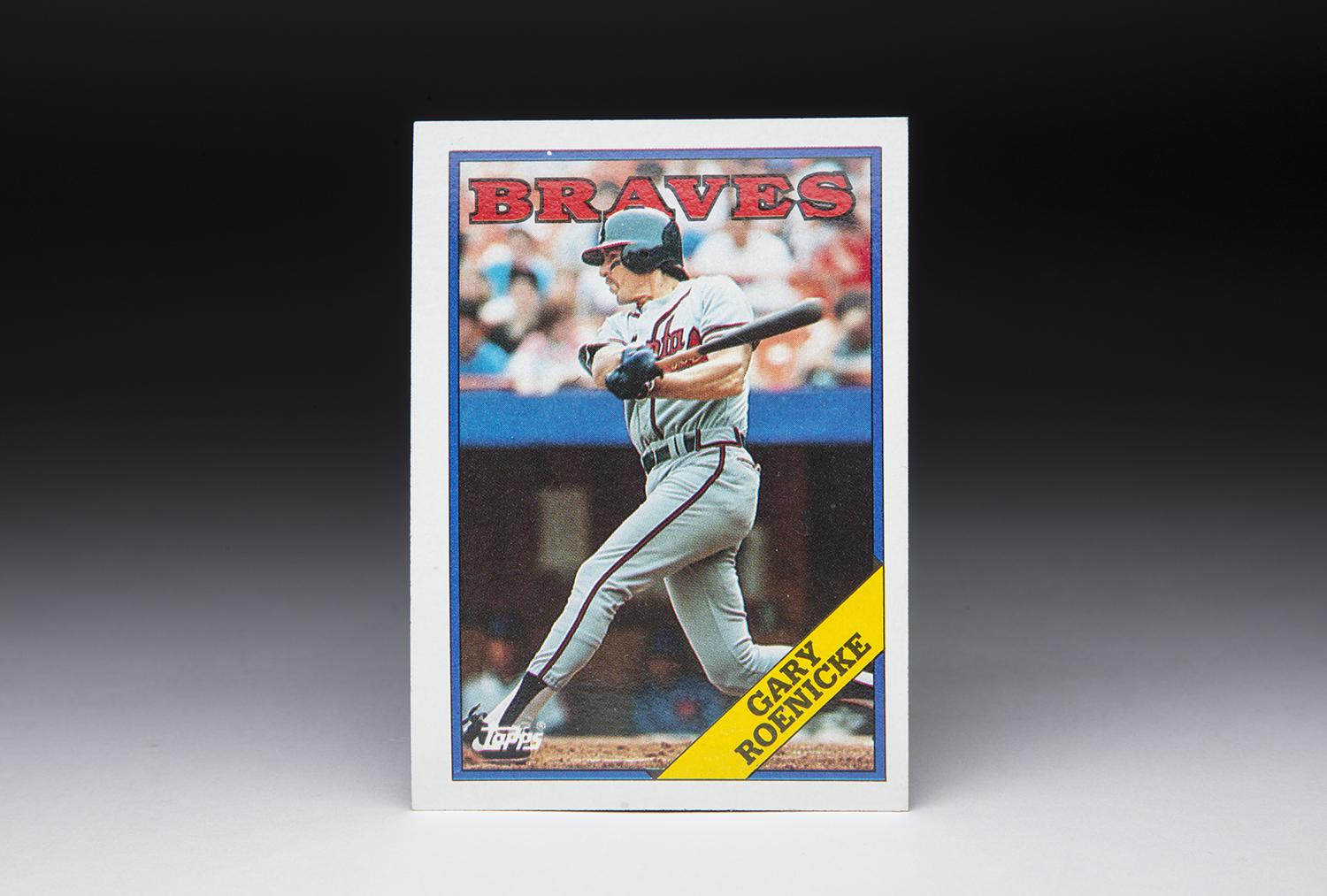

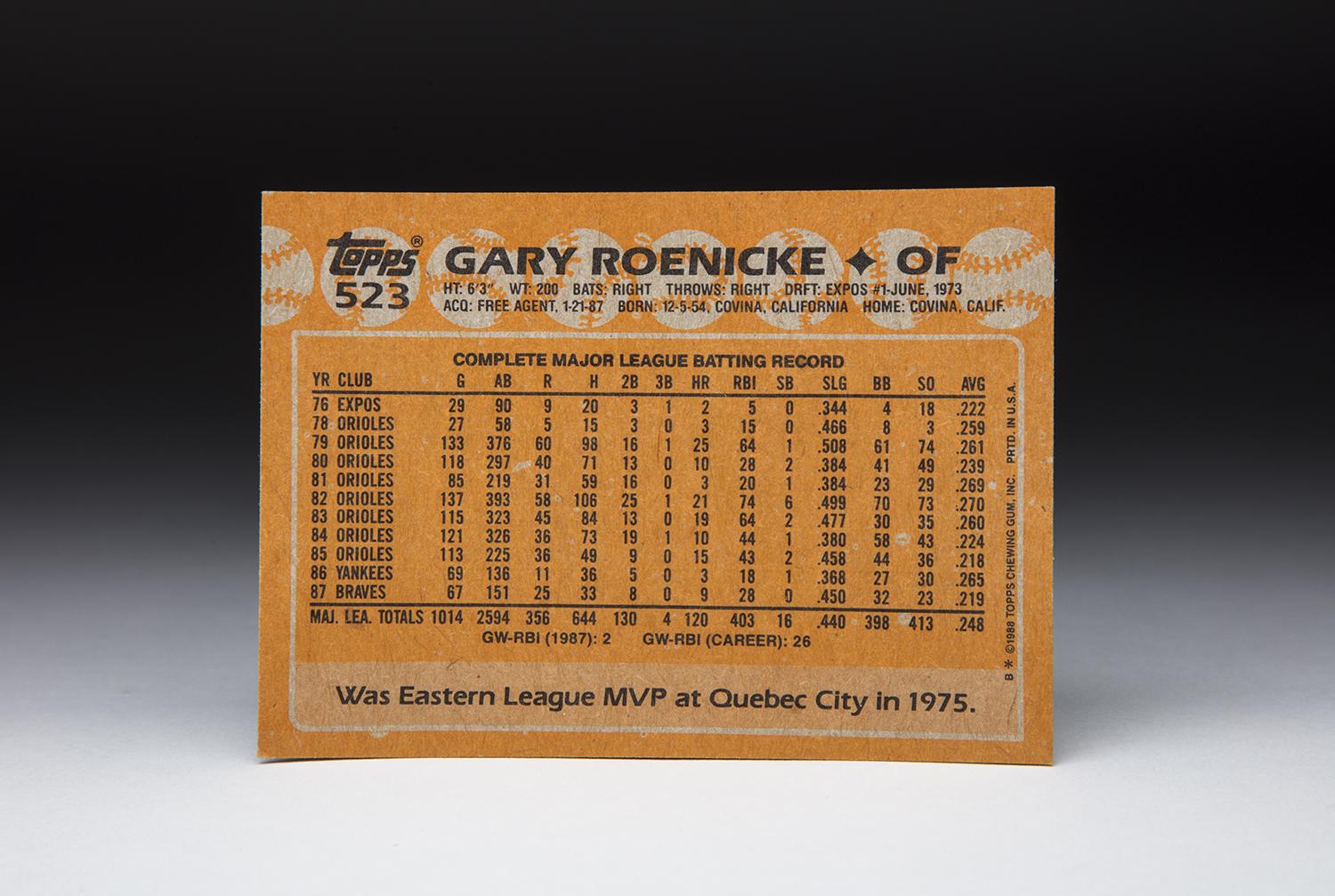

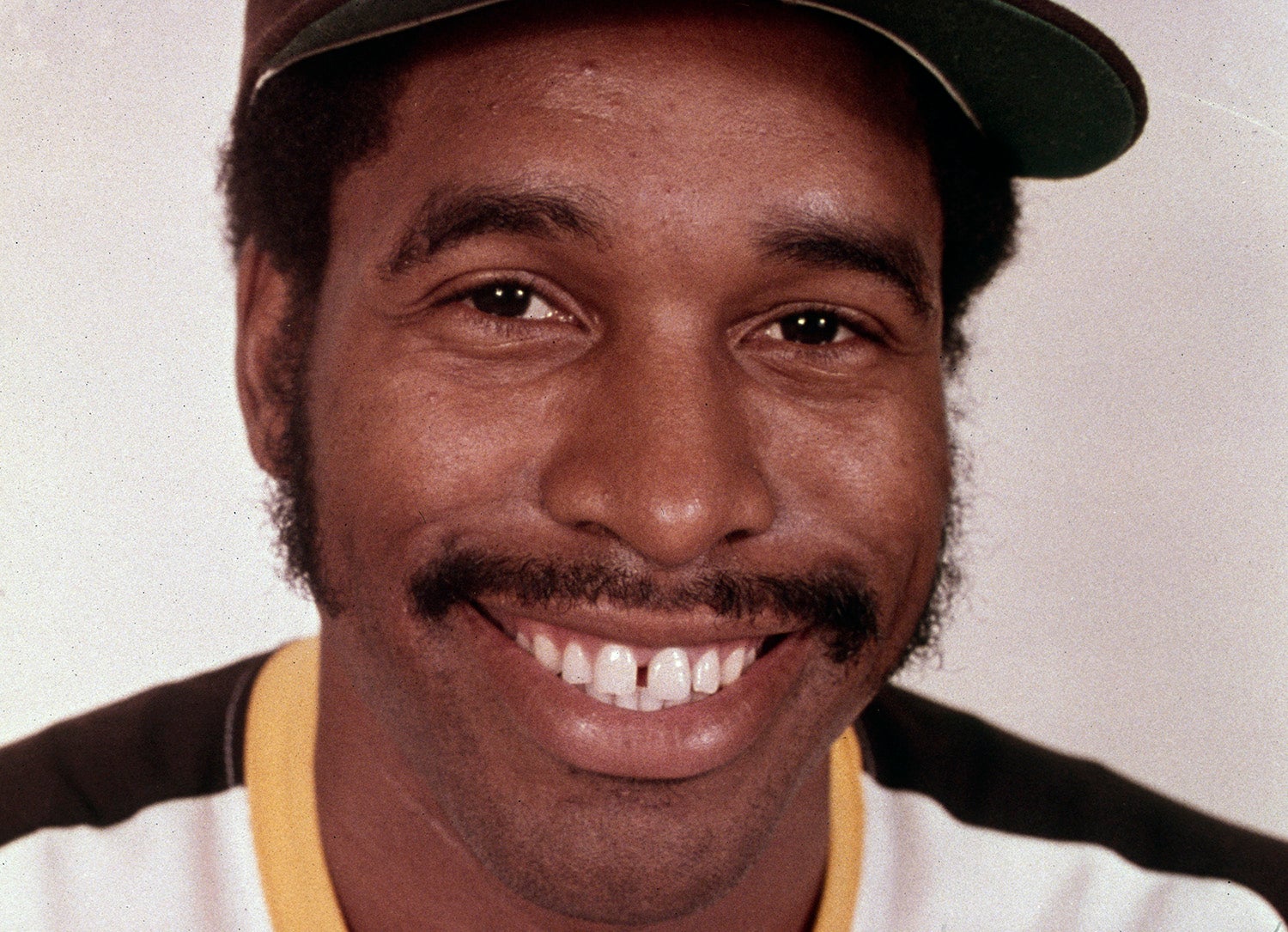

Of all the Roenicke cards, this one is my favorite. It is part of the 1988 Topps set. By this time, Roenicke had left the Orioles and was nearing the end of his career with the Atlanta Braves. Even though Roenicke had put on a few pounds and was struggling with the inevitable aging of a ballplayer, he still appears to have good balance at the plate, while executing a short, controlled swing. Like many players of the era, he is wearing lamp black under his eyes – the black substance helped reduce glare during afternoon games, this one taking place at Shea Stadium in New York.

There is one item missing from the photo, however. No longer in evidence is the small football faceguard that Roenicke used to wear earl in his career. Borrowed from a local NFL team, the faceguard attached to Roenicke’s helmet, so as to give him some extra protection against an inside fastball. He had good reason to take such a measure of security, having been hit in the face with a pitch during his days in Baltimore. By 1987, when this photo was taken, Roenicke had long discarded the faceguard but still maintained the protective earflap on his batting helmet.

The 1988 card represented the last of Roenicke’s career. He would spent part of ‘88 with the Braves, but a poor start to the season resulted in his release from the team in July. When no one claimed him, he was left out of work, giving Topps no reason to bring him back as part of the 1989 card set.

It was the end of the line for the veteran outfielder, whose career had begun 15 years earlier when the Montreal Expos selected him in the first round of the draft. As the eighth player taken overall in 1973, Roenicke was highly valued. An amateur shortstop, he was selected only five picks after Robin Yount was taken by Milwaukee, and four slots after Dave Winfield, selected by San Diego. That’s close company with two Hall of Famers.

The Expos envisioned Roenicke as a future star, but did not consider him a true shortstop. They quickly converted him to third base, a better fit given his size. Assigned to Class A Jamestown, Roenicke made a fast adjustment to professional minor league ball. He batted .298, walked as often as he struck out, and compiled an on-base percentage of .387. For a young player, Roenicke showed an especially selective eye, rarely swinging at balls out of the strike zone and more than willing to take a walk to first base.

Over the next two seasons, Roenicke climbed the Expos’ minor league ladder by putting up excellent power numbers and high batting averages. He also made the transition from third base to the outfield, a move made necessary because of ongoing problems with his back. In 1975, Roenicke played the outfield exclusively.

After a good start with the Triple-A Denver Bears to start the 1976 season, Roenicke earned a well-deserved call-up to the big leagues. He made his debut on June 8 and spent the next month in Montreal. But a low batting average with little power resulted in a quick demotion to Denver. Roenicke continued to hit well at Triple-A over the balance of the minor league season, before receiving a recall to Montreal in September.

Roenicke fully expected to have a chance to make the Expos’ Opening Day roster in 1977, but the Expos featured one of the game’s best young outfields: Warren Cromartie in left, Hall of Famer Andre Dawson in center and Ellis Valentine in right. With no opportunity to play on a regular basis, Roenicke endured another demotion to Triple-A near the end of Spring Training.

The roster decision discouraged Roenicke, but such sentiment didn’t show up in his play at Denver. He hit .321 for the Bears, the best mark of his professional career. Strangely, the Expos did not promote him in September, instead allowing his season to come to an early end.

Roenicke felt that his managers in Montreal had not given him the chance that he deserved. In particular, he did not get along well with Charlie Fox, who managed the Expos for part of 1976 before becoming the team’s general manager in 1977. It was Fox who chose not to promote Roenicke at the tail-end of the latter season, despite the young outfielder’s continued hot hitting in the minor leagues.

The Expos faced a dilemma. They knew that Roenicke had nothing left to prove at Triple-A, but they also didn’t want him sitting on the bench in Montreal. So in November, the Expos settled the matter by making a trade. They sent Roenicke and pitchers Don Stanhouse and Joe Kerrigan to the Orioles for veteran left-hander Rudy May and two other pitchers.

While the media speculated that Roenicke was merely a throw-in to the trade, the Orioles felt otherwise. Two years later, Orioles manager Earl Weaver did his best to refute the “throw-in” contention in an interview with Bill Madden of the New York Daily News. “That’s not fair to say,” Weaver argued. “I can assure you that Roenicke was well scouted. We insisted that he be part of the deal. Our people put their baseball judgment on the line when they said he had as much power potential as Ellis Valentine and Eddie Murray.”

The O’s were thrilled to have Roenicke, but he did not share that sentiment – at least not at first. That’s because the Orioles already had two established corner outfielders in Pat Kelly and Ken Singleton, and a highly capable DH in Lee May. So where would Roenicke play? Roenicke wondered if he would remain the odd man out in Baltimore, as he had in Montreal.

Undeterred, Roenicke reported to Baltimore’s Spring Training camp and battled his way onto the 25-man roster. He played sparingly in April and May before receiving news that had become all too familiar: Another demotion to Triple-A.

Roenicke tore up the International League in 1978, hitting .307 with 13 home runs in 98 games. In September, the Orioles brought him back – for good. Roenicke would never again play in the minor leagues.

The following spring, Roenicke not only made Baltimore’s 25-man roster, but became the team’s Opening Day left fielder. In only the second game of the season, Roenicke stepped in against Lerrin LaGrow, a hard-throwing reliever for the Chicago White Sox. LaGrow threw a fastball that Roenicke lost sight of, the ball tailing up and in. The pitch hit Roenicke in the face, right at the top of his mouth.

Somehow Roenicke avoided suffering any broken bones, but noticed blood pouring onto his batting gloves and the ground below. Orioles trainer Ralph Salvon needed 25 stitches to close the wound around Roenicke’s upper lip, resulting in the outfielder missing more than a week of action.

In order to give Roenicke some extra protection at the plate, the Orioles borrowed a device from another sport. A Baltimore official made his way to the locker room of the NFL’s Baltimore

Colts, who shared Memorial Stadium with the Orioles. The official picked up a helmet belonging to Colts quarterback Bert Jones and removed the faceguard. A member of the Orioles’ staff then cut the faceguard in half. For the next two years, Roenicke wore half of Jones’ faceguard during each at-bat, becoming one of the first major league players to use protective equipment to cover part of his face.

No one could have blamed Roenicke for allowing the beaning to affect his aggressiveness at the plate. But Roenicke showed few ill effects of the incident, as he spent the rest of the season sharing left field with John Lowenstein, while also filling in as a center fielder, right fielder, and DH. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t a strict platoon, since Roenicke often played against right-handed pitching. In 133 games, he belted 25 home runs, contributing to a slugging percentage of .508. He also played an excellent left field, where his deceptive speed and above-average throwing arm both served him well.

During that breakthrough 1979 season, Orioles first base coach Jim Frey noticed a stunning trend with Roenicke. “He was hit 11 times in our first 100 games,” Frey told longtime baseball writer Dick Young. “I watched him the next time up to see how he’d react. [Each time] he hit the ball against the wall or into the seats.” For the season, Roenicke was hit 12 times, but he remained fearless in his approach at bat.

The Orioles already featured a strong, power-packed lineup, with Eddie Murray at first base, Doug DeCinces at third, Singleton in right and Lee May at DH. The efforts of Roenicke and Lowenstein, whether platooning or not, only deepened the lineup further, helping the O’s win 102 games and become clear-cut winners of the American League East.

Roenicke didn’t hit much during his first exposure to the postseason, but that didn’t affect the outcome of the ALCS, as the O’s defeated the California Angels. The late-season slump had a more tangible effect in the World Series; Roenicke picked up only two hits in 16 at-bats, making him one of several Orioles sluggers to find life difficult against the pitching of the Pittsburgh Pirates. The O’s lost the Series in seven games. Roenicke was furious with himself, and all the more determined to return to the World Series.

Over the next two seasons, Roenicke’s production fell off, as he finished each season with an OPS of .724. His performance in 1980 was marred by a fractured left wrist, which kept him out of the lineup for three weeks.

Then came his career year of 1982, when Roenicke played wherever Earl Weaver asked him. Sometimes Roenicke played left field; on other days, he played right, or even first base. But wherever he played, he hit. Appearing in a career high 137 games, he blasted 21 home runs and drew 71 walks.

Although Roenicke’s reputation was that of a platoon player, he actually played far more often than a strict platoon would normally indicate. Still, he continued to be known for his association with Lowenstein. Some members of the media began referring to the tandem as the “Lo and Ro Show.”

Another good season in 1983 coincided with the Orioles’ return to the World Series. Playing under a new manager in Joe Altobelli, who liked to platoon more than Weaver, the O’s won the East and earned the right to play Chicago in the ALCS. Roenicke went wild. Though he accrued only four official at-bats, he picked up three hits, drew five walks, and compiled an OPS of 2.650. In Game 2, he hit a home run to help the Orioles win, but found himself on the bench the next day, giving way to Lowenstein. Ever the team player, Roenicke expressed no regrets about his role.

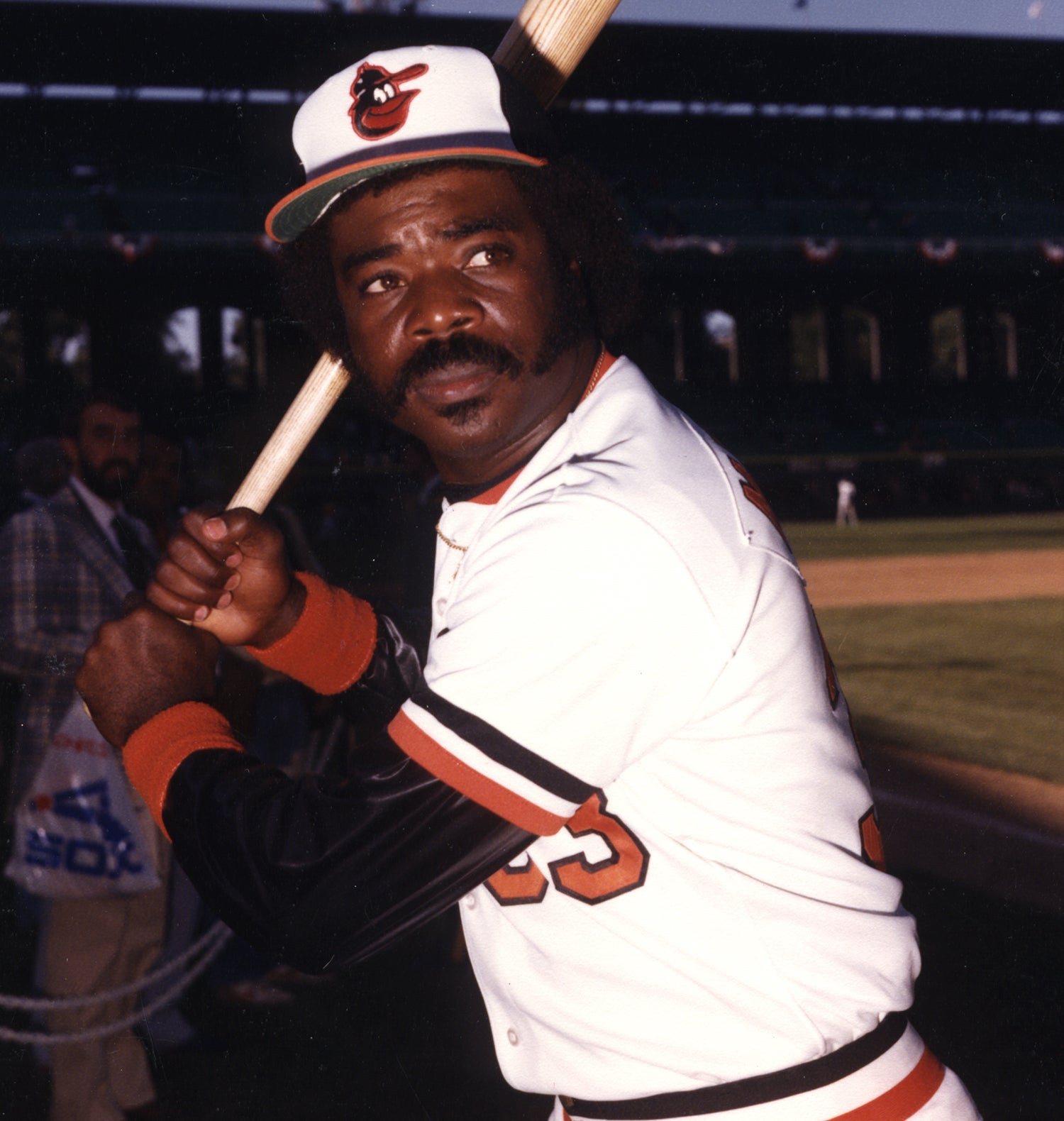

Orioles manager Joe Altobelli (pictured above) liked to platoon more than his predecessor, Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver. In 1983 under Altobelli's leadership, the Orioles won the American League East and went on to capture the World Series title that year. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

“It’s not frustrating,” Roenicke told The New York Times. “John has had another great year. That’s how we got here, with both of us sharing the position. And the most important thing is to win and get through this series.”

Arguably the most valuable player on Baltimore’s roster in the ALCS (though the award went to Mike Boddicker), Roenicke pushed the O’s into the World Series. Playing against Philadelphia, Roenicke went hitless in seven Series at-bats, but the Orioles won the world championship in five games.

Roenicke’s batting average slipped over the last two seasons, prompting the Orioles to make a trade after the 1985 season. That winter, the O’s sent him to the Yankees for infield prospect Rex Hudler and reliever Rich Bordi. The Yankees hoped that Roenicke would help balance a lineup that leaned too heavily to the left.

The Yankees envisioned Roenicke as a platoon left fielder, the right-handed half of a timesharing arrangement with young phenom Dan Pasqua. On paper, the Yankees felt they had a fearsome left field platoon, but Roenicke never found his niche in New York. Coming to bat only 136 times, he showed little power – hitting just three home runs. He put up decent numbers at Yankee Stadium, even with its Death Valley dimensions in left field, but struggled badly on the road.

All in all, Roenicke was a disappointment in New York. At season’s end, free agency beckoned. Roenicke and the Yankees parted mutually, with the veteran taking a two-year offer from the Braves. As a Brave, Roenicke showed more power, hitting nine home runs in 151 at-bats. But then came the downturn in 1988 – and the end of his playing career.

Long after his playing days, Roenicke tried his hand at managing. In 2003, he took the helm of the Montreal Royales, a team in the Canadian Baseball League, but the league folded up after only a season. Roenicke then received an offer to scout from then-Orioles general manager Mike Flanagan, his former teammate in Baltimore. As part of his job, Roenicke scouted both major league and minor league players and provides recommendations on potential trades. It was Roenicke who encouraged the Orioles to make the trade for Adam Jones, their All-Star center fielder, in 2008.

When Dan Duquette became the Orioles’ general manager, Roenicke’s contract was not renewed. Since leaving the O’s, he has done work as a coach in China, teaching the game to young players. Roenicke’s legacy also includes his son Josh, a pitcher who has appeared in parts of six major league seasons and is now toiling in the Mexican League. That makes this author feel old; it is hard to believe that 30 years have gone by since the elder Roenicke last played in a major league game.

It isn’t often that so-called platoon players create such vivid memories, the way that Roenicke once did. Of course, Roenicke was far more than a platoon player, as evidenced by his contributions to a pair of World Series teams in Baltimore. He was a player who persevered, through some difficult times in the Montreal farm system and through a beanball incident that might have damaged the career of a lesser man. Platoon player or not, Gary Roenicke made his mark on our game.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty