- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Joe Niekro

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Joe Niekro

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

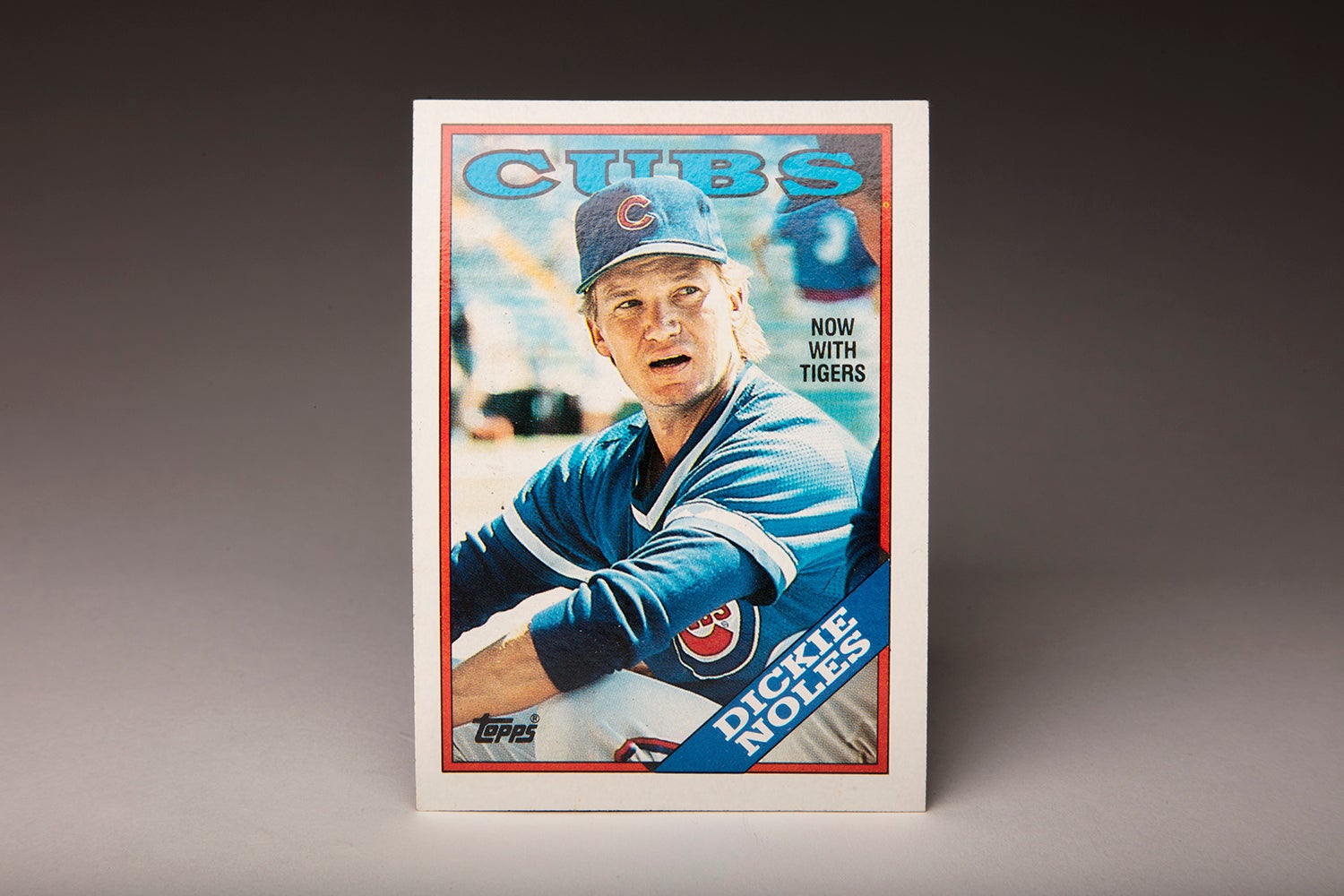

In 1988, Joe Niekro appeared on a Topps card for the final time. Although the photograph is obviously not a shot from an actual game, it still gives us a taste of Niekro’s motion, and his intensity.

Based on the number of empty seats in the background, the photo was likely taken long before game time. Niekro is still wearing his warm-up jersey; his team, the Minnesota Twins, wore pinstriped jerseys as part of their actual road uniform, not the solid black top that is on display here. The stadium, which may or not be the Oakland Coliseum (often the site of Topps photography) appears so completely empty that this is probably several hours before the start of the game, or perhaps even on an off day. With his right arm extended fully forward, we can only guess that Niekro has just thrown one of his trademark knuckleballs, a pitch that he learned after his major league career began.

Perhaps most striking on this card is Niekro’s facial expression. He appears to be biting his lip, an indication of the effort and seriousness that he put into his job, even during a warm-up session on a day when he probably didn’t even appear in a game.

I’m reminded of Niekro’s intensity, and his professionalism, when I think about the fantasy camp that the Hall of Fame used to stage back in the early 2000s. The camp ran from 2004 to 2008 and featured not only a group of Hall of Famers, but other retired stars of the game. Back in 2006, Niekro took part in that fantasy camp, assisting his brother Phil, a member of the Hall of Fame. On a Saturday afternoon that October, Joe Niekro pitched both ends of a fantasy camp doubleheader. It was a remarkable display of endurance for a man who was 61, but appeared to be in excellent shape. Little did any of us know that later that month, Joe Niekro would be gone, the victim of a condition that offered little in the way of warning.

After pitching the twinbill that day in Cooperstown, Niekro and his brother took part in a special program at the Hall of Fame and Museum’s Grandstand Theater. A number of other players from the camp also participated, telling stories and answering questions from the audience. As much as anyone on that panel, the Niekro brothers enthralling the audience that night. In particular, Joe Niekro stood out for being outgoing, funny and genuine.

The overriding theme of Joe’s comments involved his sincere love and admiration for his Hall of Fame brother. That night, I learned just how close Joe and Phil were, and saw firsthand a complete lack of jealousy on the part of Joe toward his more famous brother. There was no sibling rivalry here. Quite the contrary, Joe exuded respect and love for a big brother, one who just happened to be a Hall of Fame pitcher. Joe’s heartfelt remarks nearly brought some of the audience members to tears, not easy to do on a night that was otherwise filled with joking and laughter.

Joe also talked about his son, Lance, a major league first baseman at the time. Lance had made the roster of the San Francisco Giants only three years earlier. To say that Joe was beaming with pride about his son would be an understatement of epic proportions. Fittingly, Lance would take Joe’s place at the next two Hall of Fame fantasy camps, assisting his uncle Phil and spending some quality time with camp members and staff alike.

Joe’s 2006 appearance in Cooperstown turned out to be the final public appearance of his life. It was a great baseball life, but one that began with many moments of difficulty, as he tried to establish himself as a major leaguer. Remarkably, Joe would achieve achieved most of his pitching glory after turning 30. Much like Mike Easler and Bill Robinson, Niekro was that rare player who was better in his 30s than in his 20s.

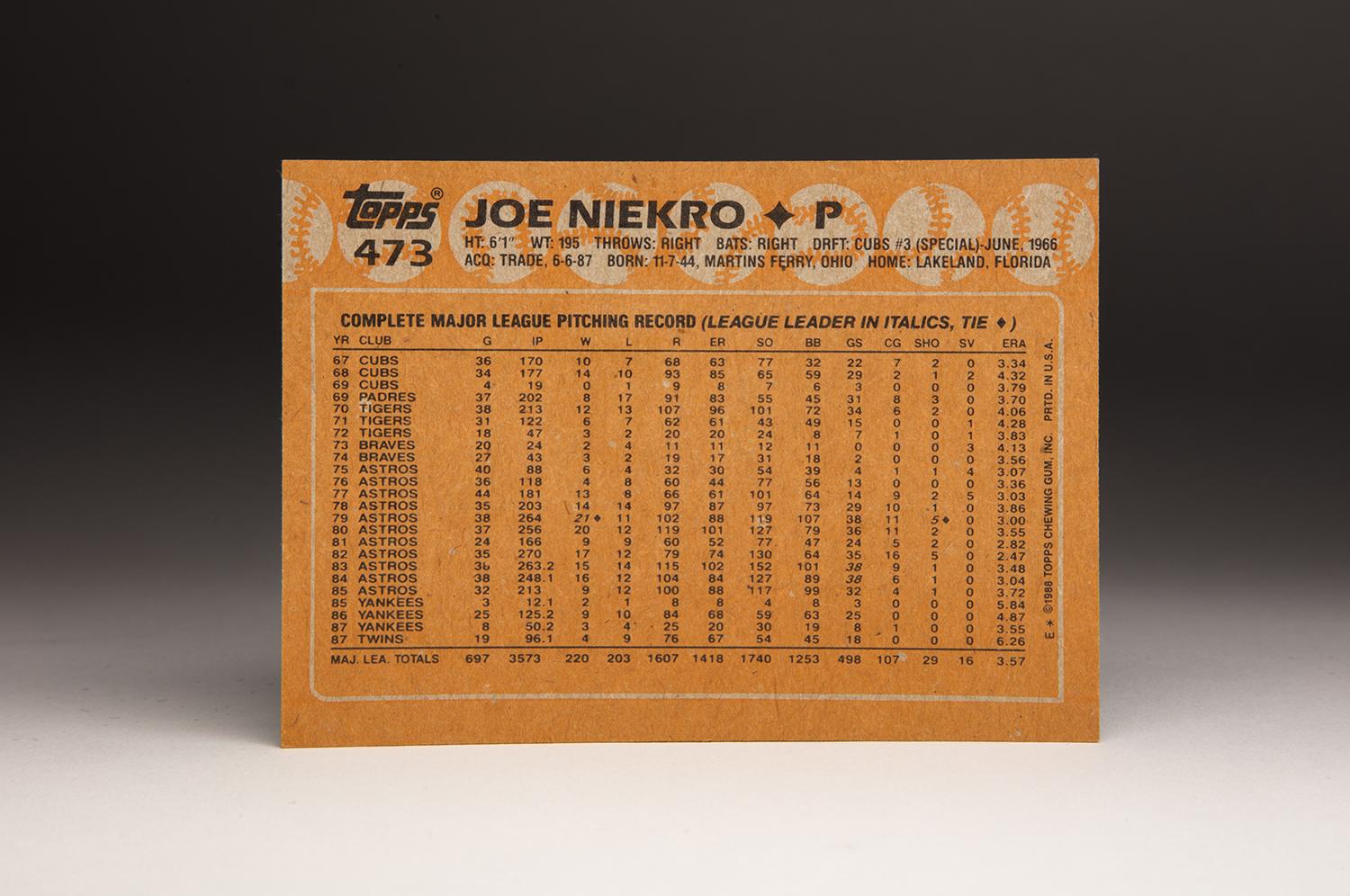

Those early years offered only momentary glimpses of Niekro’s future success. The Chicago Cubs selected him in the third round of the June 1966 draft and brought him to the big leagues just one year later. He pitched well, using his combination of a fastball, slider, and occasional curve ball to win 10 of 17 decisions while posting a 3.34 ERA. Then came the sophomore jinx. The Cubs made him their Opening Day starter, but Niekro faltered throughout the 1968 season, in a year that was extremely favorable to pitchers, Niekro’s ERA soared to 4.31, a full run above the National League average.

After only three starts in 1969, the Cubs traded Niekro, sending him and two prospects to the expansion San Diego Padres for veteran reliever Dick Selma. Niekro pitched decently for the new franchise, but toiling for an expansion club did little for his won/loss record. Suffering from a severe lack of run support, Niekro won only eight games and lost 17.

Niekro was still only 24 years old, and the building Padres decided that they wanted an older and more experienced pitcher in their rotation. That winter, they packaged Niekro with utility infielder Dave Campbell, sending them to the Detroit Tigers for 28-year-old Pat Dobson. It was a trade that allowed Niekro to join a better club that was only two years removed from a world championship.

Tigers manager Mayo Smith placed Niekro into his starting rotation, giving him 34 starts. Niekro became a workhorse, logging over 210 innings and struck out over 100 batters for the first time in his career, but pitched inconsistently. He won 12, lost 13, and posted an ERA a tick over 4.00. On a staff with a clear-cut ace in Mickey Lolich, Niekro became the No. 2 starter.

After the 1970 season, the Tigers fired Smith and replaced him with Billy Martin, who kept Niekro in the rotation to start the season. But after he lost his first three starts and put up a mediocre line in his fourth start, Martin moved Niekro to the bullpen. He would spent most of the summer in the bullpen before receiving a string of starts in August, but failed to find a niche in either role. At season’s end, his ERA stood at 4.42, leaving his status for 1972 up in the air.

The Tigers demoted Niekro to Triple-A to begin the 1972 season, before bringing him back to Detroit in May. Once again, he shuttled between the rotation and the bullpen, putting up middling numbers.

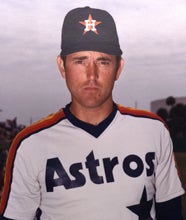

Niekro returned to the minor leagues in 1973. In August, the Tigers tried to slip him through waivers, but the Atlanta Braves put in a claim. That transaction turned out to be the break that Niekro needed, giving him the chance to play with his brother Phil, a Braves mainstay since the early 1960s. At the time that he joined the Braves, Joe remained a standard fastball/slider pitcher. But the reunion with Phil exposed him to the virtues of the knuckleball.

Thanks to childhood lessons from his father, Joe had known how to throw the pitch going back to his earliest days in pro ball, but never dared use it in a major league game. “He had the pitch in his hip pocket,” Phil later told the Associated Press. “He just had to reach back and use it. But his past managers and coaches discouraged him, and it took him a while to build up some confidence.” As Phil went on to say in his interview with the AP, “He was confused. He thought the world was giving him on him. I wouldn’t let him quit on himself.”

Phil encouraged Joe to experiment and refine the pitch, which had allowed Phil to become the ace of the Braves. At first, Joe mixed in the knuckleball with his fastball and slider. Joe learned all he could about the knuckleball from Phil. Joe altered the grip slightly, allowing him to throw the knuckleball harder than his brother.

But success did not come immediately. Working almost exclusively out of the Braves’ bullpen, Niekro struggled over the second half of 1973 before showing improvement in 1974. Phil hoped that the Braves would show patience with Joe. The following spring, Joe pitched well in exhibition games, but just before Opening Day, the Braves told him that they planned to send him back to Triple-A Richmond.

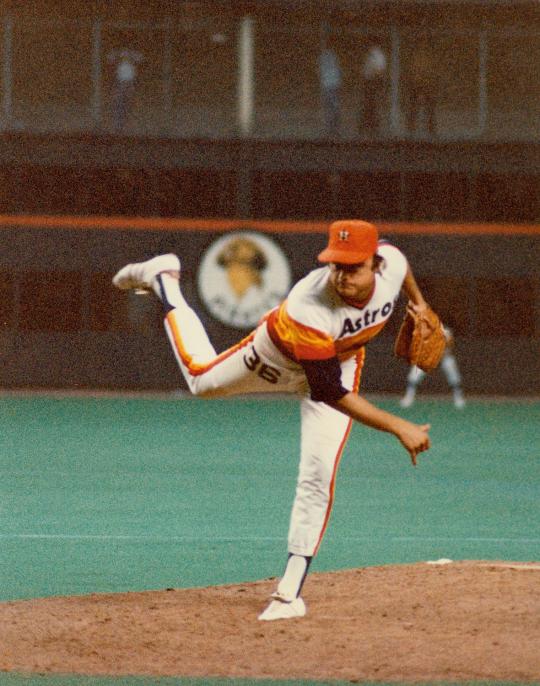

Joe told Braves general manager Eddie Robinson that he had no interest in a return to the minor leagues, not at his age. So he recommended a trade to another team. Robinson came through, sending Joe to the Houston Astros for the sum of $35,000. It would turn out to be the bargain of the decade for the Astros, who had just found their eventual complement to hard throwing right-handers like J.R. Richard and Joaquin Andujar.

Once again, though, success did not come immediately for Niekro. Pitching in relief for the next two seasons, he did well, but without much fanfare or glory. And then in 1977, Astros manager Bill Virdon gave Niekro an expanded role. Logging 180 innings as a combination starter and reliever, Niekro struck out 101 batters, won 13 games, saved five others, and whittled his ERA down to 3.04. By this time, Joe had made the knuckleball his primary pitch. At the age of 32, Niekro had essentially found himself, initiating the second phase of his career as a dominant pitcher.

In 1978, the Astros moved Niekro into the rotation fulltime. Over the span of three seasons, he compiled over 700 innings and won 55 games, including a pair of back-to-back 20-win seasons. In 1979, Niekro fared so well that he made his first All-Star team, won the Sporting News’ National League Pitcher of the Year Award, finished second in the Cy Young Award balloting (behind Hall of Famer Bruce Sutter), and even placed sixth in the MVP voting. And in a rather delicious coincidence, his 21 wins tied brother Phil for the National League lead.

In 1980, Niekro once again reached the 20-win milestone. The 20th win came at a most opportune time, in the one-game NL West tiebreaker against the Los Angeles Dodgers. Niekro bested the Dodgers, sending them home and pushing the Astros to their first postseason berth in franchise history.

Niekro’s stellar pitching continued in the NLCS. In Game 3, Niekro pitched a shutout for 10 innings, settling for a no-decision in an 11-inning win for the Astros. But that outing left Niekro unavailable to pitch the final two games for the Astros. The Astros lost both of those matchups, dropping the series in five difficult games.

From 1977 to 1984, Niekro enjoyed the peak of his Astros tenure. It’s worth noting that his Astros career coincided with several other standout pitchers on the same staff, including Richard, Nolan Ryan and Mike Scott. Those three pitchers were terrifying to face, Ryan and Richard because of their otherworldly fastballs and Scott because of a devastating split-fingered fastball. Yet, Niekro won more games (144) as a member of the Astros than any of those titans, giving him a franchise record that has not been matched. (Roy Oswalt, at 143 wins, would fall just short of the Niekro standard.)

In 1985, Topps printed its final card of Niekro as a member of the Astros. With his effectiveness waning, the Astros traded him in mid-season to the New York Yankees for a package headed up by young left-hander Jim Deshaies. The trade was not popular with his Astros teammates, who knew that they would miss a fun-loving teammate with a good sense of humor.

While Joe enjoyed his time in Houston, the trade allowed him to rejoin Phil, who had become a Yankee in 1984. “Of course, I’m excited,” Joe told Mike McAlary of the New York Post. “Phil has always been my idol. Now I’ll get dressed in a locker next to him.” Given the presence of the Niekro brothers, 40 percent of the Yankee rotation now relied on the knuckleball.

With the Yankees hunting for a division title, Joe won two of three late-season starts, but the team fell short of winning the American League East. The final day of the season did bring some fun, however. Phil won his 300th career game, while Joe was given the task of being the Yankees’ honorary pitching coach for the day.

Joe Niekro pitched for the Atlanta Braves from 1973-74, posting an ERA of 3.76 in 47 games. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Joe Niekro spent the majority of his professional baseball career pitching for the Houston Astros, from 1975-85. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The following spring, Phil was released by the team, in a move that stunned Yankee fans, but Joe pitched the entire season in New York. He mostly struggled for the Yankees, perhaps because of his departure from the Astrodome, where the pitcher-friendly environment and the neutral weather conditions made the knuckleball even more effective. Another possibility was the emotional effect of Phil’s release on Joe, which would not have been surprising given their close relationship.

Joe returned to the Yankees as their No. 5 starter in 1987, but a slew of injuries affected the team’s offense, causing a need for left-handed hitting. In early June the Yankees acquired backup catcher Mark Salas from the Twins – in exchange for Niekro.

After Niekro joined the Twins, he became involved in a major controversy. Pitching in a game in Anaheim, Niekro became the subject of a spot inspection by the umpiring crew. As the crew looked over Niekro, umpire Steve Palermo noticed a small emery board and some sandpaper dropping out of the right-hander’s hand. With the evidence now on the ground, home plate umpire Tim Tschida ejected Niekro; a 10-game suspension from league president Bobby Brown soon followed.

As he served the ban, Niekro made an appearance on David Letterman’s late night show, where he poked fun at himself by coming onto the set while bearing a tool belt featuring a power sander, a container of Vaseline, and several emery boards.

After serving the ban, Niekro returned to the Twins and finished out the season but was ineffective. He returned to the Twins in 1988, but continuing struggles led to his release in May. With that, Niekro’s long pitching career came to an end.

For the most part, Niekro stayed out of baseball in his post playing days. But in the 1990s, he took on a role that fell out of the mainstream. He became the pitching coach for a women’s team, the Colorado Silver Bullets, joining a staff that worked under the direction of his brother Phil, the team’s manager. After a two-year stint with the Silver Bullets, Niekro took on another unconventional project: teaching the knuckleball to a young girl named Chelsea Baker, who would go on to throw a pair of perfect games in Little League.

Niekro also appeared regularly at golf outings and fantasy camps, including the one at Doubleday Field in Cooperstown. By all accounts, he appeared to be in excellent physical condition, as evidenced by his ability to pitch both ends of that doubleheader in Cooperstown. After that camp concluded, Niekro returned to his Florida home.

Only three weeks later, Niekro came down with a severe headache and chest pains. He took himself to a local hospital in Plant City, where he collapsed shortly after arrival. From there, he was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa. Just one day later, Niekro died from the effects of an aneurysm. He was only 61.

In response to the sudden and unforeseen tragedy, Niekro’s daughter Natalie started the Joe Niekro Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to research and treatment in the fight against brain aneurysm, hemorrhagic strokes, and AVMs (arteriovenous malformations).

I remember hearing the news of Niekro’s passing and how stunned it left me. Whenever we hear that someone we just saw a few days or weeks earlier has died, it always hits a bit harder. The news became even more difficult because of the impression that Niekro left that night in the Grandstand Theater, when he seemed so vital, so caring, and so appreciative of his family.

In reporting his death, several media outlets recounted Niekro’s involvement in the 1987 controversy, when he was found with the sandpaper and emery board. That story needed to be mentioned, but it did not define Joe Niekro. And that’s certainly not what I remember most about Niekro whenever I hear his name. No, I always remember him for what he revealed to us in Cooperstown during that Hall of Fame fantasy camp in 2006. That’s when Joe Niekro showed us his true character: a good man who was a hard worker, a loving brother and a proud father.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

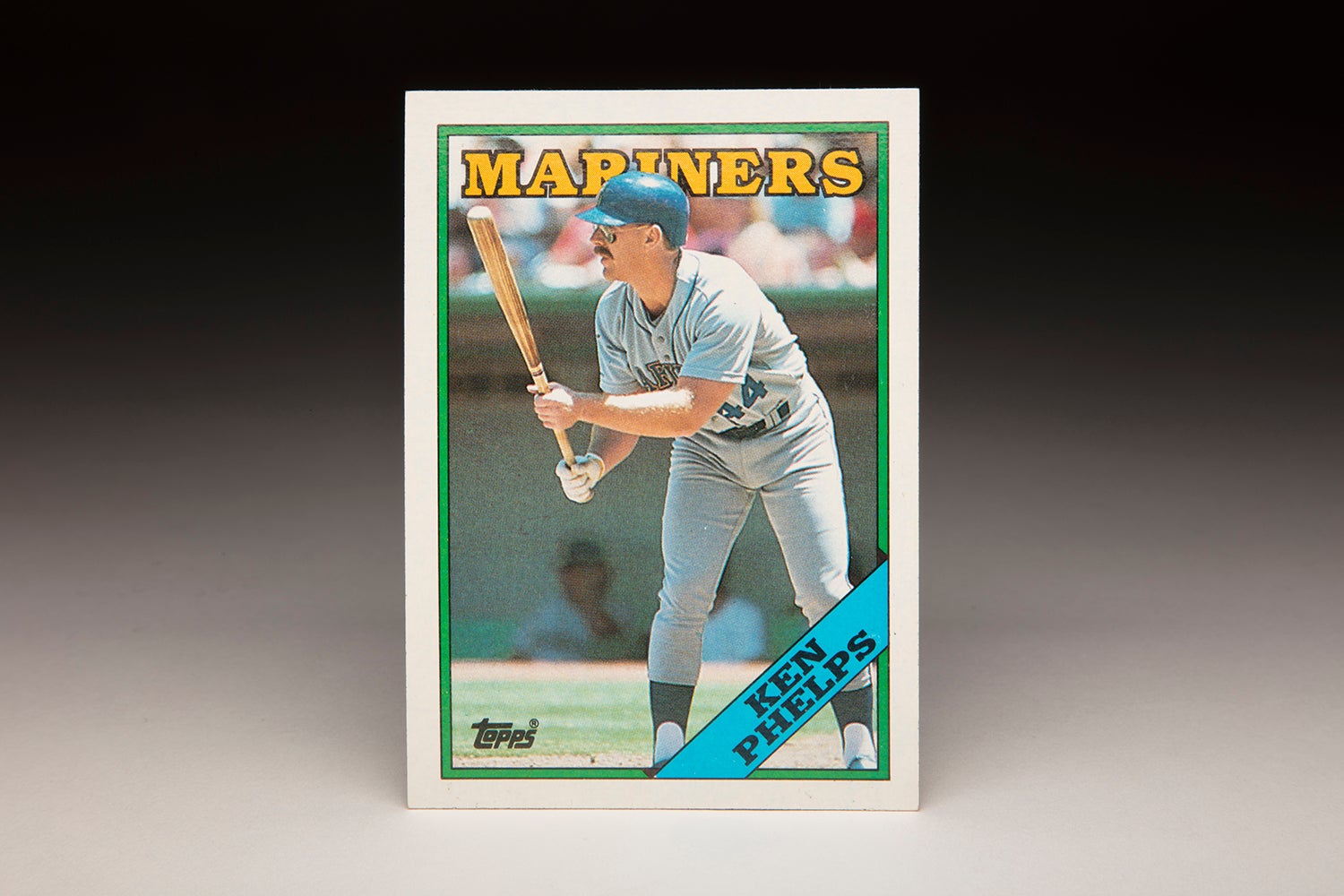

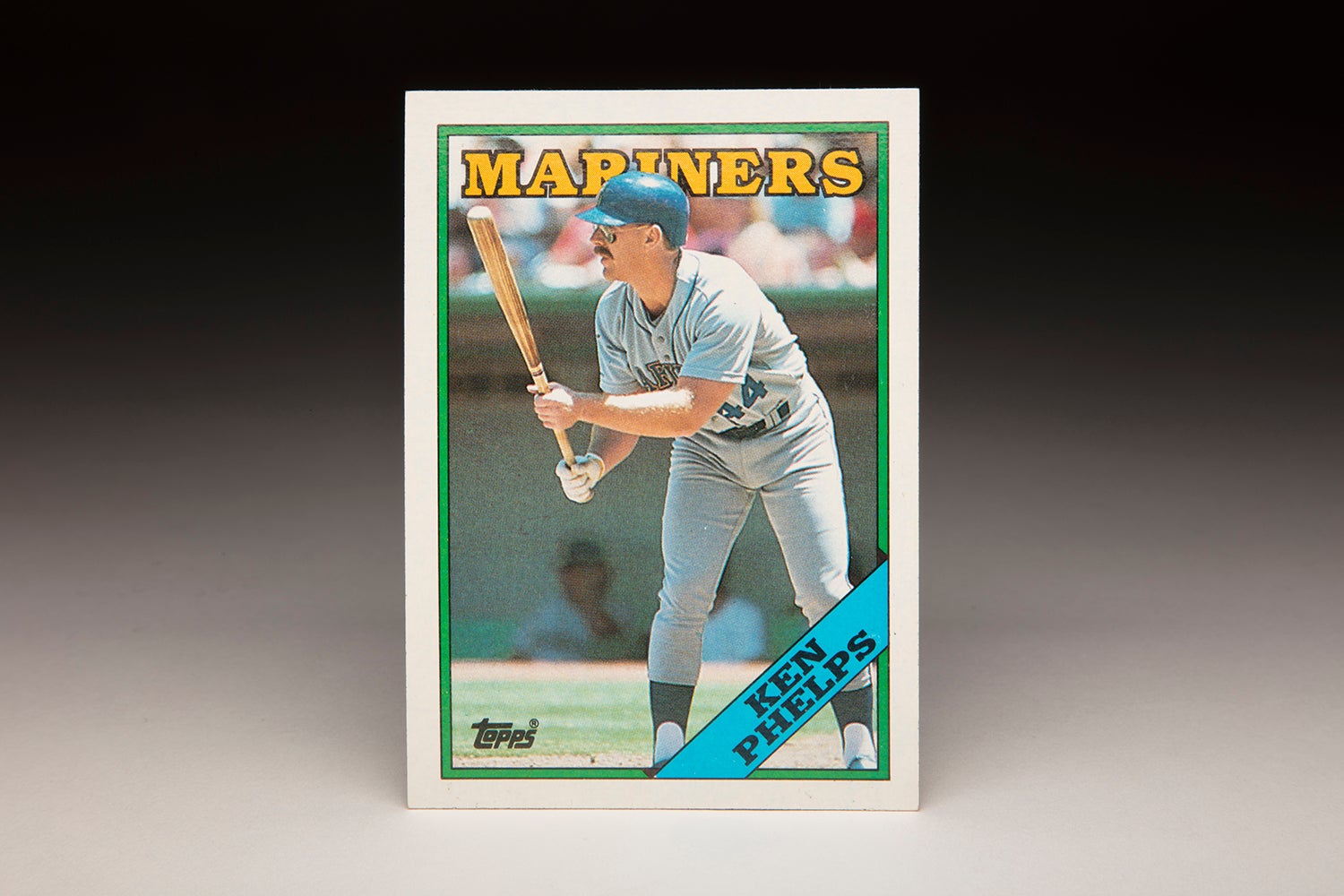

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

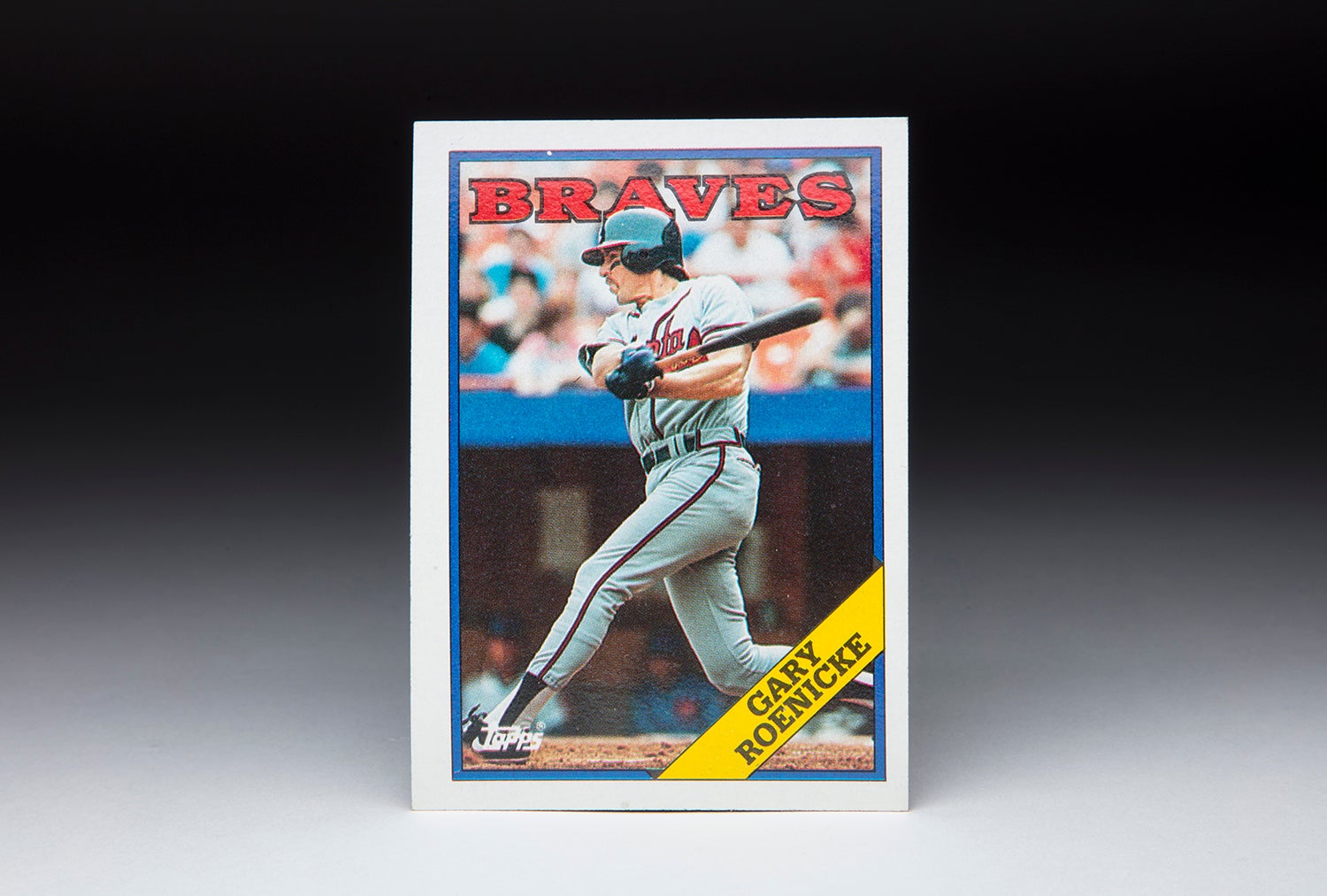

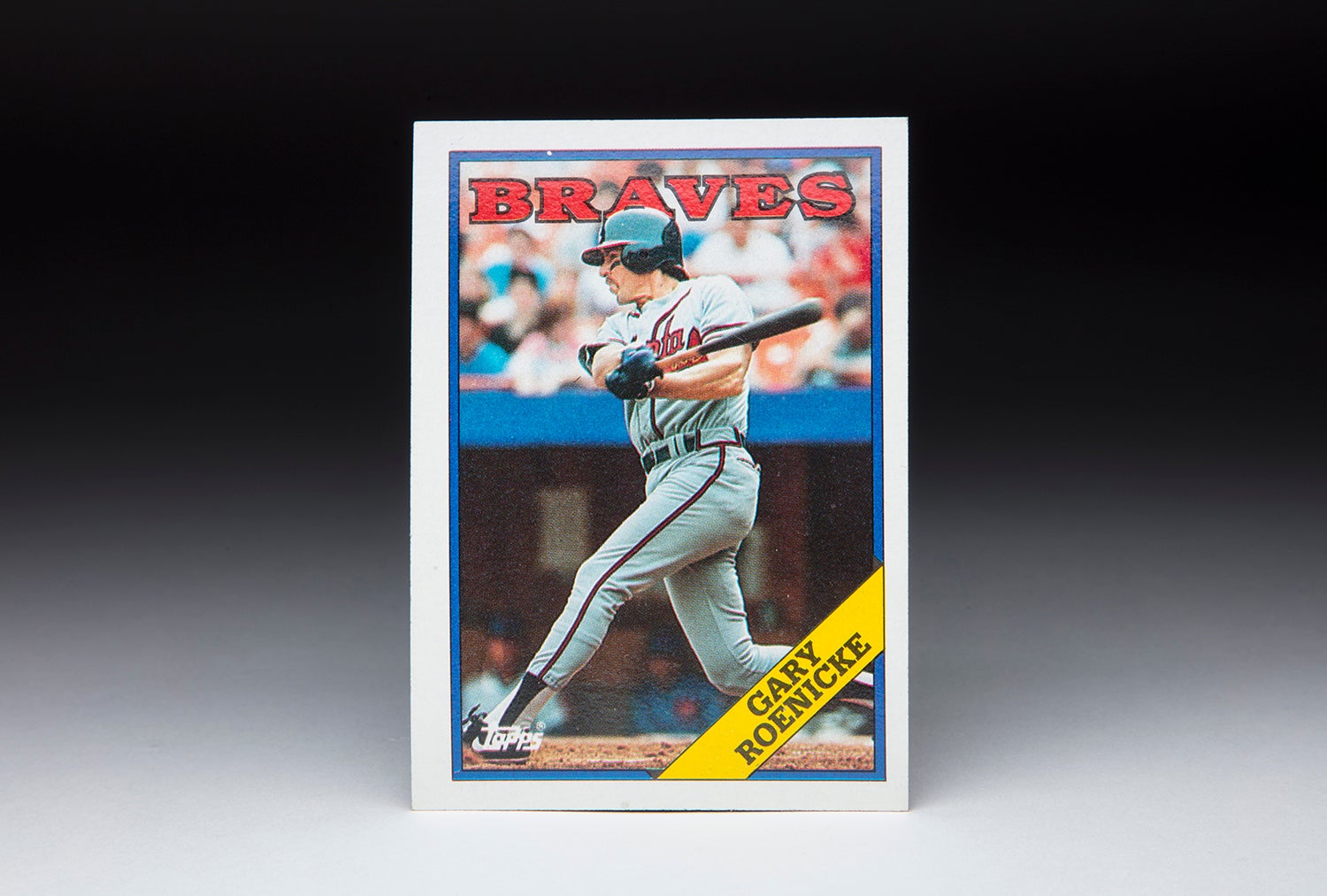

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

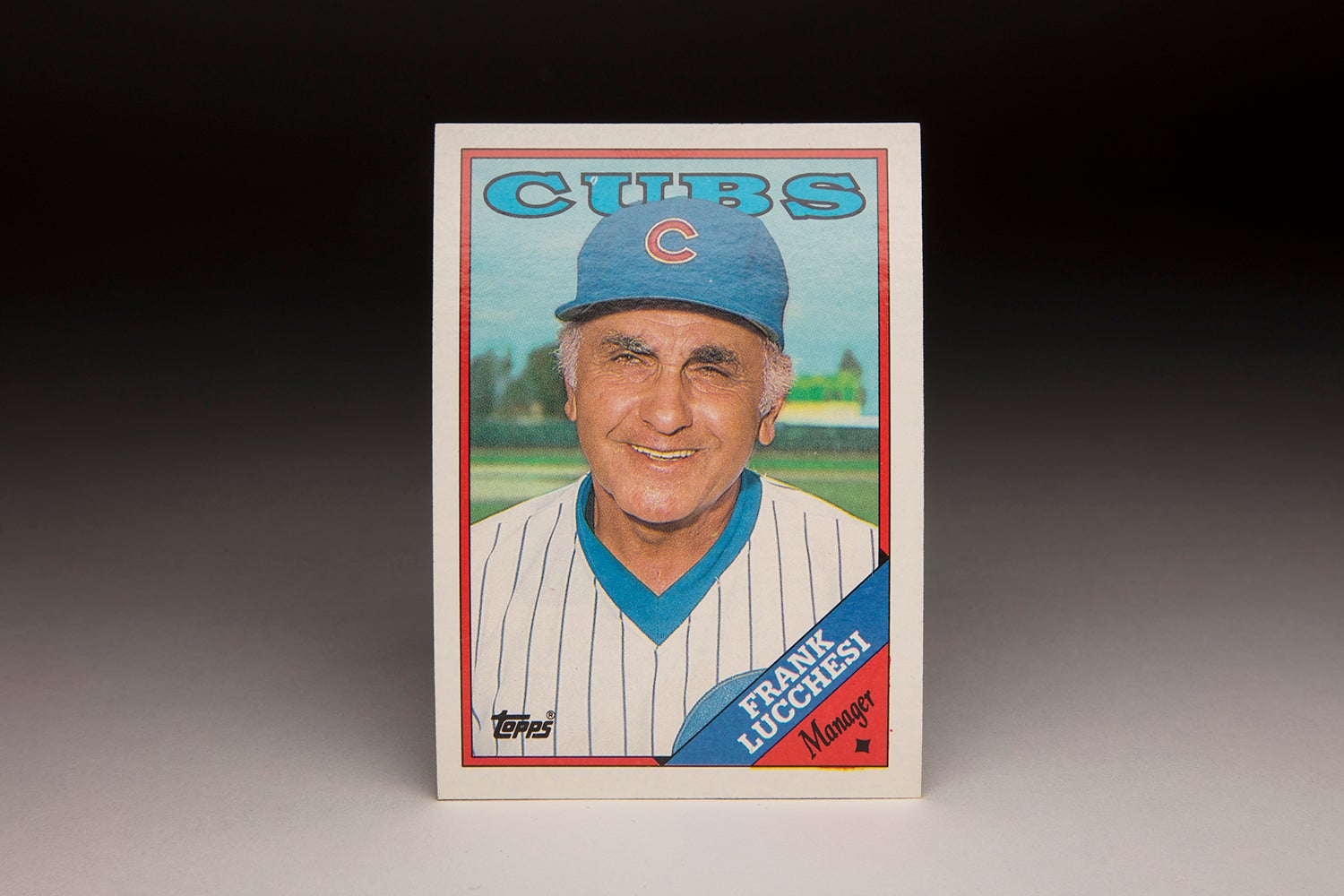

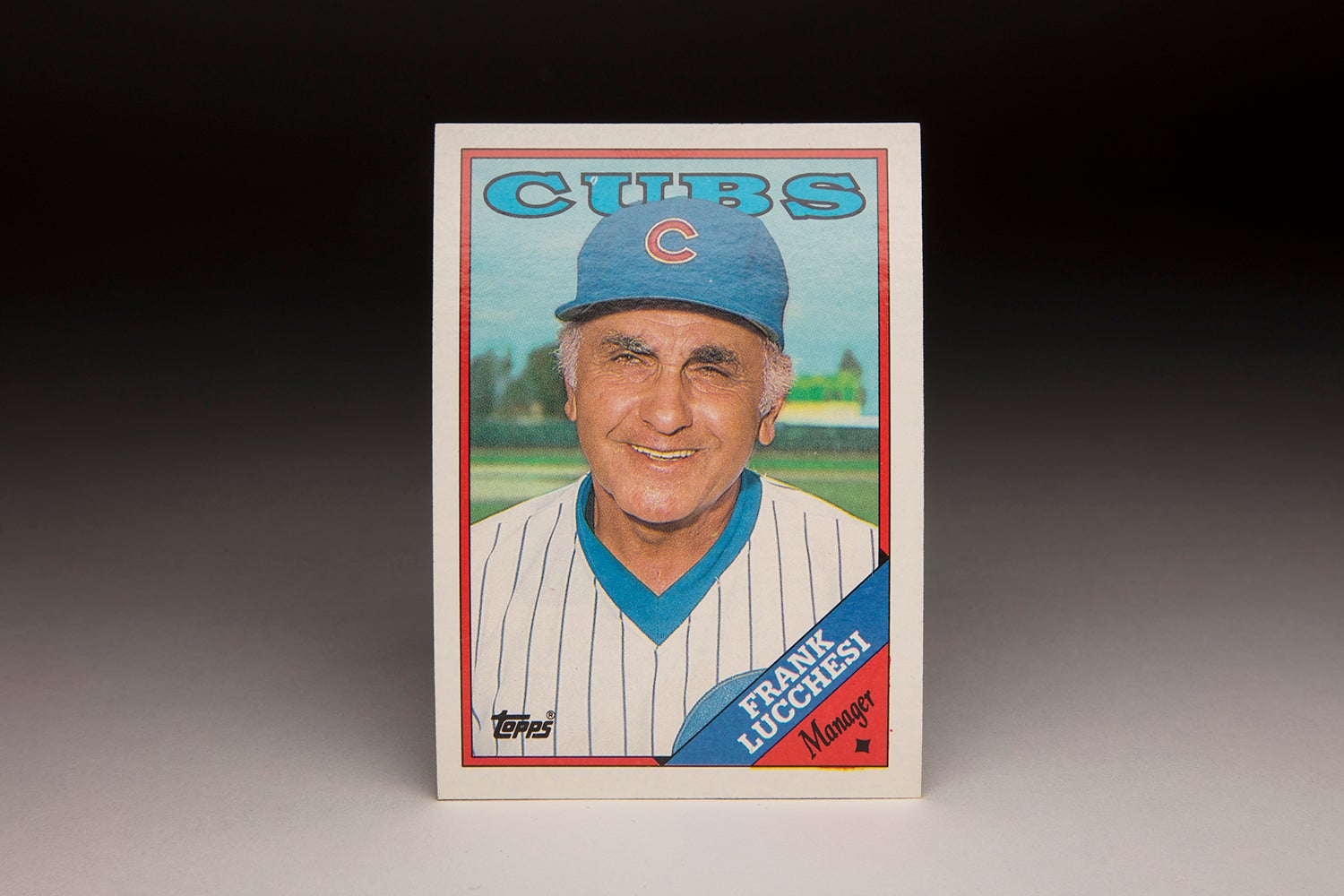

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Frank Lucchesi

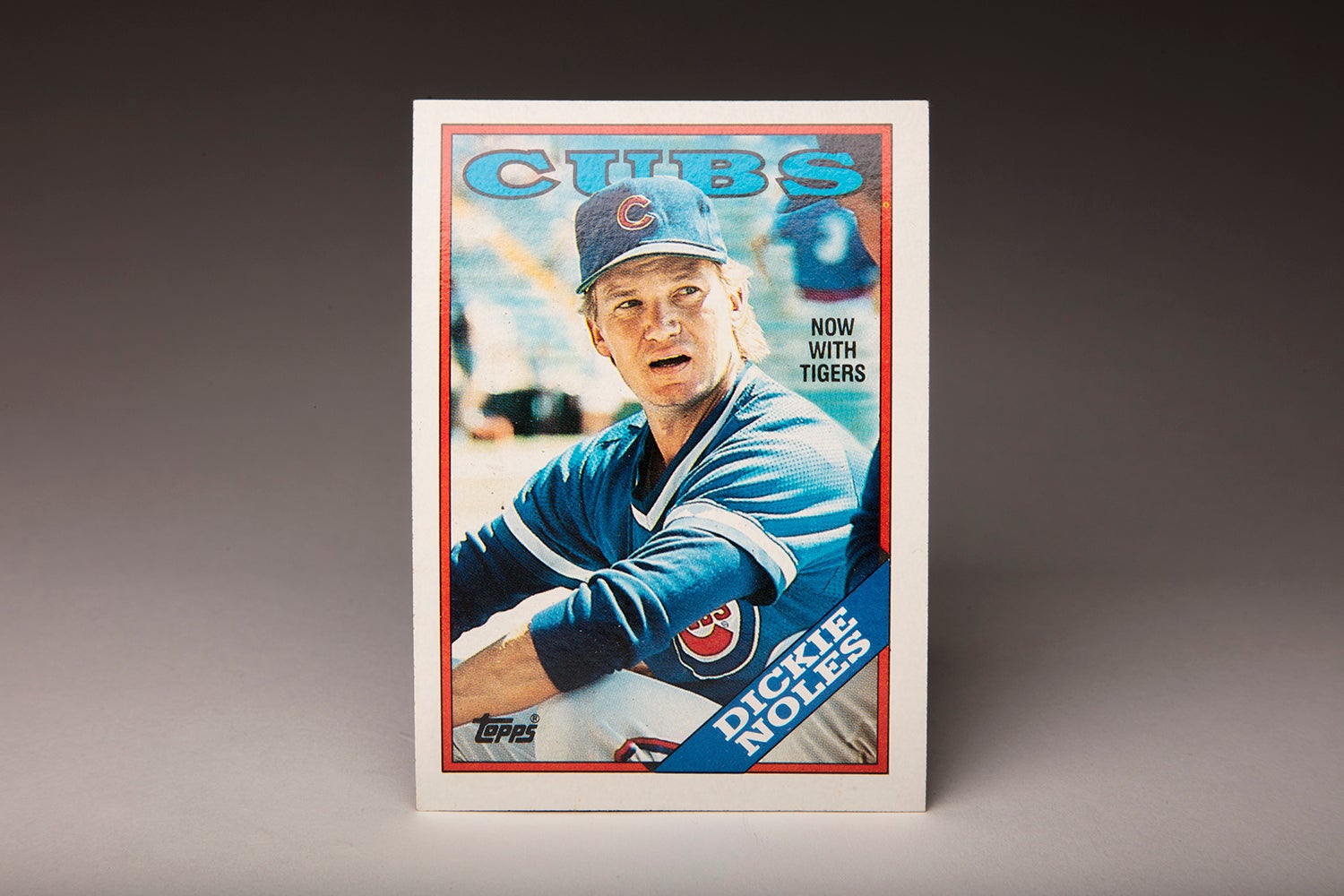

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Ken Phelps

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Frank Lucchesi