- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Bert Campaneris

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Bert Campaneris

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

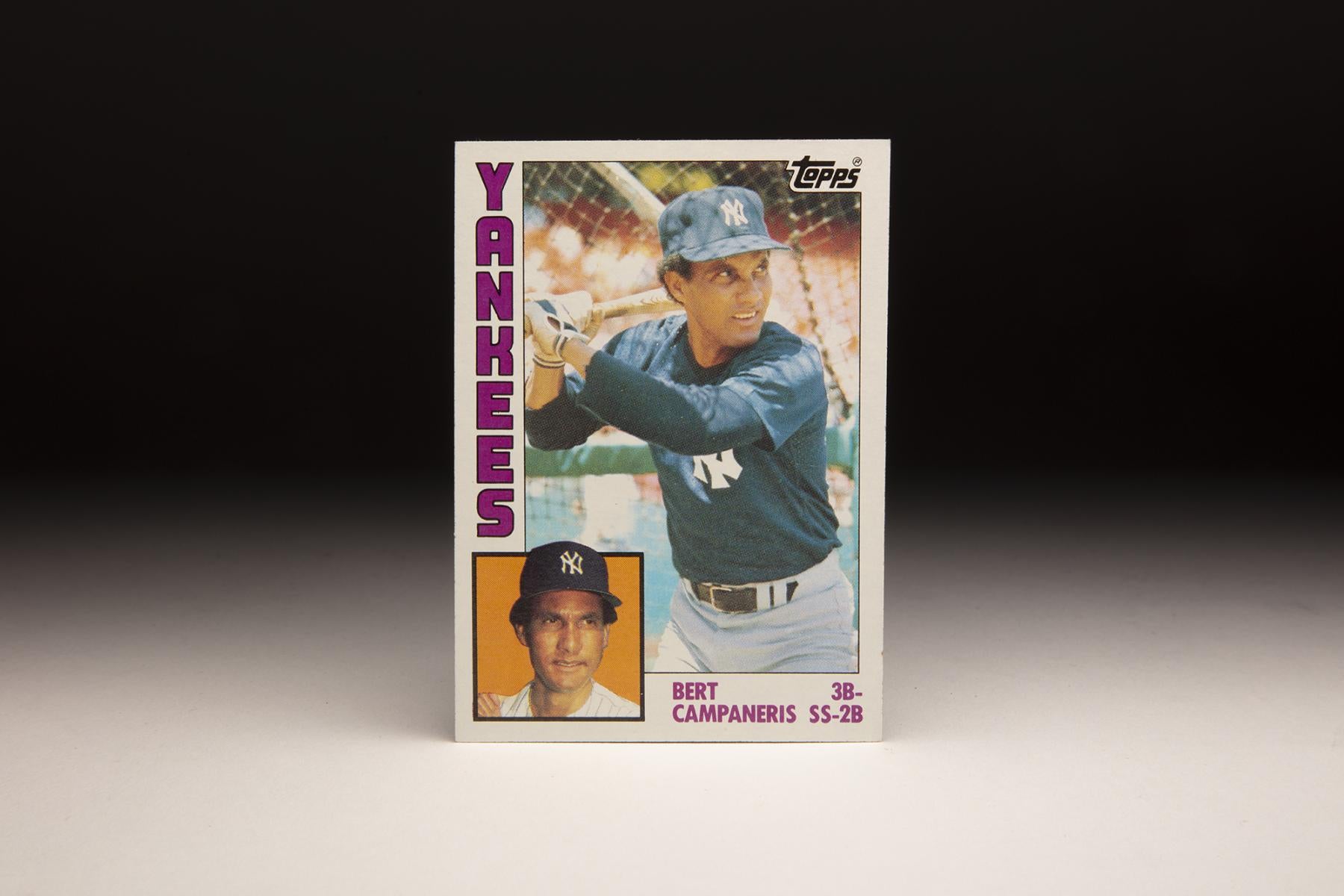

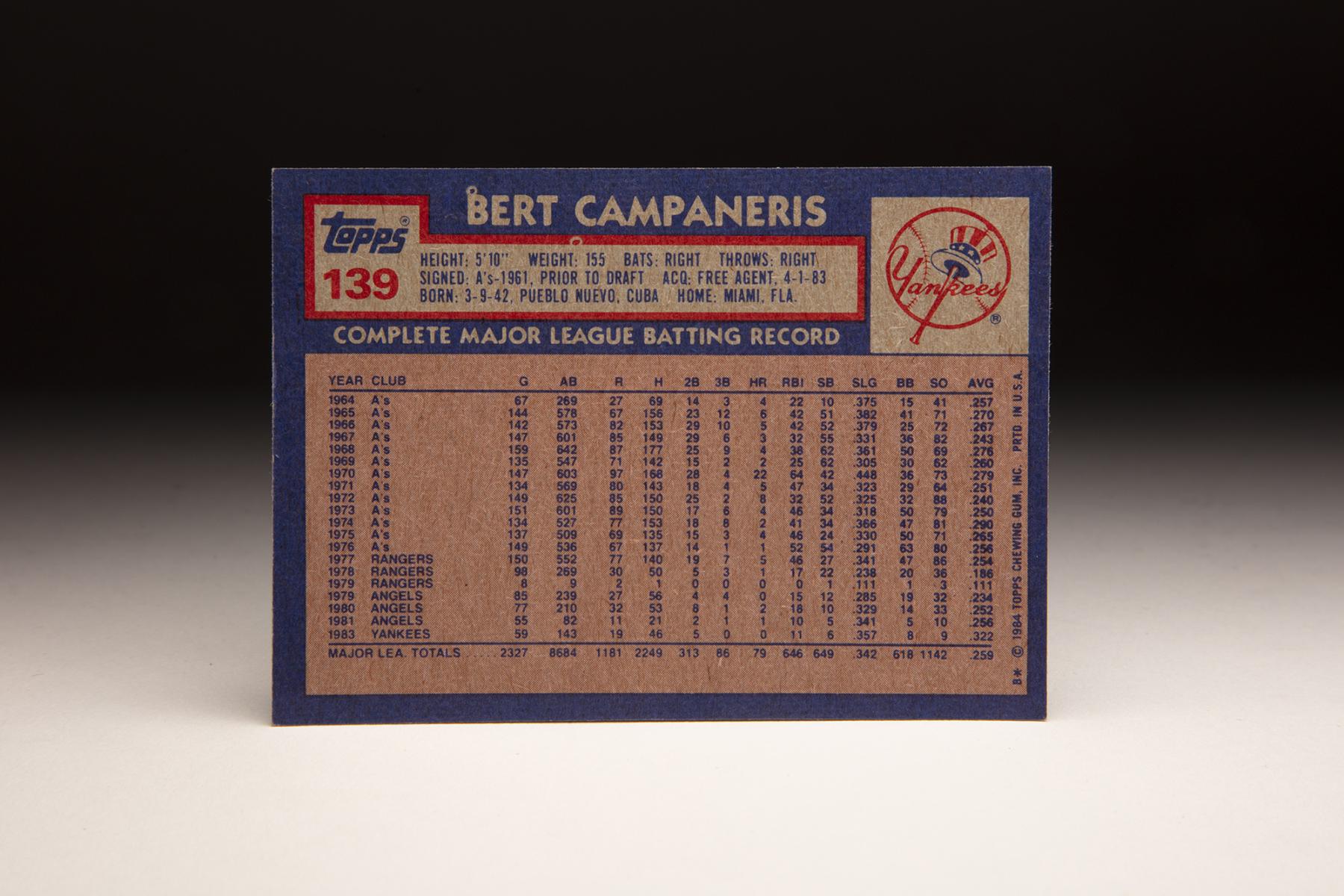

For some reason, the 1984 Topps set rarely seems to be a topic of discussion. It has become a forgotten set, or at the very least, an ignored set. Maybe that’s because of its odd formatting, with the team name running vertically down the left side of the card, rather than the usual horizontal formatting used to display team names.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

The set also bears a resemblance to the 1983 set in that each player card featured two photographs: a larger image (often an action shot) and a smaller inset photo of the player in portrait. Topps had seemingly become so enamored by the two-photo format that the company brought it back for another season. In 1983, the two photos seemed like a refreshing novelty, but by 1984, it could have been categorized as “too much of a good thing.”

Of all the 1984 Topps cards, one of my favorites belongs to Bert Campaneris. It’s a rare shot of Campaneris wearing the colors of the New York Yankees, and not the teams he is most identified with: the Oakland A’s, Texas Rangers and California Angels. It’s also interesting in that Campaneris is not wearing the Yankees’ official jersey. No, that’s a pre-game jersey that the Yankees used for a number of years in the 1980s.

The card’s photograph shows him intently eyeing his next pitch in the batting cage. When you’re a utility infielder in your 40s, there is no other way to take batting practice. It’s a fitting photograph of Campaneris, emblematic of the kind of work ethic and determination that he needed to stick with the Yankees for the entire season.

This is also the final card that Topps ever produced for Campaneris, a player whose career dates back to the mid-1960s. In my opinion, final cards don’t receive their just recognition. While they’re never as financially valuable as a player’s rookie card, they have just as much sentimental value to this collector. It’s a way for a card company to say farewell to a longtime, beloved player.

A native of Cuba, Campaneris had first arrived in the states in 1962, when the A’s signed him as an amateur free agent and assigned him to Daytona Beach of the Florida State League. Hitting .290 in 100 games at Daytona, Campaneris earned a fast call-up to Double-A Binghamton later that summer. Playing in 13 late-season games, Campy hit a scalding .364.

Despite his success at Binghamton, the A’s sent him back to Class A ball to start the 1963 season. In what turned out to be an injury-plagued season, he returned to Binghamton and batted .308 in 35 games. In 1964, the A’s moved their Double-A franchise to Birmingham, Ala. Campaneris again played Double-A ball, excelling with the Barons over a half-season. When the parent Kansas City A’s lost starting shortstop Wayne Causey to injury, they summoned Campaneris as his replacement.

After an all-night plane ride, one that afforded him little chance to sleep, Campaneris arrived at the ballpark. Kansas City’s equipment manager, regarding the 155-pound Campaneris as too frail to be a ballplayer, initially refused to give him a uniform. Eventually, the equipment man gave in, awarding Campy one of Kansas City’s garish green-and-gold outfits.

Starting at shortstop that night, Campaneris stepped to the plate for the first time. On the very first pitch he saw from Minnesota’s sinkerballing left-hander, Jim Kaat, Campaneris surprised everyone by hitting a home run. This was the same Campaneris who had hit all of two home runs during his two and a half years in the minor leagues.

In the seventh inning that night, Campaneris matched his first at-bat by hitting a second home run against Kaat. With a pair of surprise long balls, Campy tied a modern day record for most home runs in a major league debut. The 22-year-old speedster also did a lot more that night, racking up a single, a stolen base and an acrobatic catch on a pop-up into short left field.

As a rookie, Campaneris played well for the A’s. Off the field, his life did not seem so glamorous. As he settled into his new apartment in Kansas City, loneliness began to plague Campaneris. He was separated from his mother, father, and seven brothers and sisters, all of whom remained behind in Cuba, living under the regime of Fidel Castro. Very shy in public, Campaneris had no girlfriend or wife, and few friends of any kind. Sensing his reserved nature, several of the A’s attempted to incorporate Campaneris into the social atmosphere of the clubhouse.

Not surprisingly, Campaneris’ tendency to stay to himself may have been caused by problems with a new language. At the time, major league teams did not employ paid interpreters to serve as liaisons with Latino ballplayers. There was also no one around to teach Campaneris how to improve his English. At first, he spoke so little of the language that teammate Diego Segui, a fellow Cuban who eventually became his best friend on the team, served as his interpreter for media interviews.

Although members of the Kansas City coaching staff struggled to communicate with him, they came away impressed with Campaneris, particularly his daring base running style and his footspeed.

“He’s got guts,” A’s coach Gabby Hartnett told Kansas City sportswriter Joe McGuff. “He’s got the best pair of wheels I’ve ever seen. I saw a lot of great base stealers, including Max Carey, but I wouldn’t rate any of them ahead of this kid.”

A’s third base coach Luke Appling, another Hall of Famer, described Campy’s baseball instincts as “exceptional.”

Campaneris used those instincts, along with his speed and quickness, to become a strong contributor in the mid-to-late 1960s. On offense, Campaneris hit in the .260 to .270 range and emerged as one of the American League’s top basestealers. For three straight seasons, he stole at least 50 bases, reaching a high point of 62 in 1968.

In the field, Campaneris flashed tremendous range to both sides, but did have a tendency to bobble the routine grounder.

He committed more than 30 errors in three of his first four full seasons before settling down in 1969. As with his base stealing techniques, Campy improved his fielding skills through a strong work ethic that separated him from other players.

In 1970, Campaneris broke out in an unusual way, showing a side to his game never before seen. He slugged a career-high 22 home runs, after hitting no more than six in his best previous performance. He also led the league in stolen bases with 42, batted a solid .279 and earned some support in the American League MVP balloting.

In 1971, Campaneris could not repeat his power numbers; he finished the season with only five home runs. He didn’t hit for a high average either, struggling through an up-and-down season at the plate. Some members of the organization, including manager Dick Williams, believed that he was over-swinging, in an effort to match or exceed his 1970 home run total.

“We called him ‘Baby Hondo,’ because everybody thought he swung the bat like Frank Howard,” Athletics reliever Fingers told me in the late 1990s. The 6-foot-7 Howard weighed well over 250 pounds, while Campaneris was only 5-foot-10 and weighed barely 155 pounds.

While Campaneris struggled with the bat in 1971, his defensive play helped the team enormously. Now a sure-handed shortstop, Campaneris cemented a strong defensive infield that featured Dick Green at second base and Sal Bando at third base. Buttressed by an excellent interior defense, power hitting, and a deep pitching staff, the A’s won their first American League West title.

Like many of the A’s, Campaneris struggled during his first venture into the postseason. Facing the vaunted pitching staff of the Baltimore Orioles, Campaneris scratched out only two hits in 12 at-bats. The A’s lost the ALCS, three games to none.

Orlando Cepeda, who played with Campaneris briefly in 1972, raves about the subtle, understated importance of the scrappy shortstop to the Oakland teams of the seventies.

“Campy Campaneris, it’s too bad he don’t get the recognition he deserved,” laments Cepeda. “Boy, he was the guy. I remember that Dick Williams told me that year, ‘This is my MVP. If we don’t have this guy on this ball club, no way we’re gonna win the pennant.’ Campy was a guy who played every day; he’s a great teammate, a great human being.”

Campaneris batted only .240 in 1972, but led the league in stolen bases and sacrifice bunts and played a dandy shortstop, helping the A’s win their second straight AL West title. The A’s moved on to play the Detroit Tigers in the ALCS; it was during that series that Campy became embroiled in the worst controversy of his career.

In Game 2, Tigers reliever Lerrin LaGrow hit Campaneris in the foot with a fastball. Believing the pitch to be thrown with intent, Campaneris spiraled the bat in the direction of LaGrow, who ducked under the bat as it passed the mound.

The bat toss instigated a wild bench-clearing brawl and infuriated Tigers manager Billy Martin.

American League President Joe Cronin suspended Campaneris for the balance of the ALCS.

A few days later, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn announced that Campaneris would have to sit out the first seven games of 1973 without pay, but would be deemed eligible for any potential 1972 World Series games involving the A’s.

The A’s ended up winning the series with the Tigers, setting up a World Series matchup against the “Big Red Machine” of Cincinnati. Perhaps distracted by the swirl of controversy around him, Campaneris batted a paltry .179 against the Reds, but the A’s won a tight seven-game Series to take home their first franchise title since their days in Philadelphia.

In 1973, Campaneris turned in similar offensive numbers to what he had done in ’72, but his postseason would produce far more positive vibes. In the ALCS against Baltimore, Campaneris paced the Oakland offense with a .333 batting average, two home runs and three stolen bases. And then in the World Series, Campy batted .290 with three more stolen bases, as the A’s repeated as world champions.

Campaneris posted one of his best offensive seasons in 1974, when he batted .290 with 34 stolen bases. The American League’s beat writers took notice, voting him 15th in the league MVP race. And for a third consecutive season, Campy earned selection to the All-Star Game.

More postseason glory came the way of the A’s in ’74. The A’s manhandled the Los Angeles Dodgers, four games to one, thanks in large part to Campaneris’ bat. He hit .353 with an .859 OPS, played a brilliant shortstop and created his usual havoc on the bases. Some observers felt that Campaneris should have won the World Series MVP, but the award instead went to his teammate, Rollie Fingers.

After another solid season in 1975, Campaneris returned to Oakland for what would be his final season with the A’s. With a new system of free agency looming, Campaneris asked owner Charlie Finley for a five-year contract.

Although Finley liked Campaneris, he rejected the request. Campy played out a one-year contract and found his five-year offer in free agency – courtesy of the Texas Rangers. The length of the contract surprised some, given that Campy was now 35 years old.

In order to make room for Campaneris, the Rangers moved veteran shortstop Toby Harrah to third base. With the Rangers, Campaneris qualified for another All-Star Game berth and led the league with 40 sacrifice hits, but clearly lost a step on the base paths. He was caught stealing 20 times against 27 successful stolen bases, a poor ratio.

The 1977 season would turn out to be Campaneris’ last as a regular. In 1978, he slumped so badly that the Rangers benched him in August. He would finish the season with a paltry .186 batting mark, by far the worst of his career. When 1979 came around, the Rangers turned shortstop over to young Nelson Norman, making Campaneris an unhappy reserve infielder. In early May, the Rangers dealt Campaneris and his hefty salary to the California Angels. Over the next two seasons, he split time with two other shortstops, Freddie Patek and Jim Anderson, playing reasonably well in the time-sharing role.

In 1981, the Angels promoted top prospect Dickie Thon to shortstop, making Campaneris a fill-in and a defensive caddy at third base. With his contract running out that fall, the Angels allowed him to become a free agent. No major league team showed interest, so he signed a contract to play third base in the Mexican League.

Given his age, Campaneris’ days as a major leaguer appeared to have ended. But then in the spring of 1983, he showed up unannounced to the Yankees’ camp in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. The 41-year-old desperately sought a job as a utility infielder. Knowing that the Yankees needed a backup who could fill in at third, shortstop, and second, Campy approached Martin, the Yankees’ manager at the time and his onetime nemesis from the 1972 playoffs. Martin, known for maintaining intense grudges, would have surprised no one by dismissing Campaneris. Instead, Martin challenged Campy to make his Opening Day roster.

Most unwittingly, Campaneris became a source of controversy. When Yankees public relations director Ken Nigro heard Martin talking about Campaneris trying to make the team, he thought the manager was kidding. According to Bill Madden’s entertaining book, Damned Yankees, Nigro made a disparaging remark about Campaneris. Martin responded angrily to Nigro, wondering why he would have the audacity to offer input on player personnel.

“If you don’t mind, pal,” Martin said to Nigro, “I’ll make the personnel decisions around here.”

Campaneris didn’t care about negative perceptions; he simply wanted to continue his career and do so with the Yankees.

“All my life I’ve thought about one day playing for the Yankees.” Campaneris told Murray Chass of the New York Times. “Everybody wants to play for the Yankees. That’s why I came here first.”

Martin treated Campaneris with an open mind. As much as Martin had become angered with Campaneris for hurling his bat at one of his players in 1972, he realized that the incident was not an accurate indication of his character or personality. In truth, Martin respected the veteran infielder as a fiery, combative sparkplug who always hustled. In some ways, Martin looked at Campaneris and saw himself.

Martin did not include Campaneris on the Opening Day roster, but recommended that the Yankees place him at Triple-A Columbus. When Willie Randolph went down with an injury early in May, Campy received the call and filled in capably. For the season, he hit .322 as a backup to Randolph at second base and to Graig Nettles at third base. He also gained a bit of notoriety by playing third base during Dave Righetti’s famed Fourth of July no-hitter.

Although Campaneris came to bat only 143 times in 1983, he did everything the Yankees asked him to do. In addition to reaching base at a .355 clip, he showed some of his old speed, and played reasonably well at both second and third base. So it was with some level of astonishment that the Yankees chose not to re-sign Campaneris at the end of the ’83 season, letting him become a free agent.

No one else signed Campaneris, but he did find work as a minor league instructor with the Angels, where he worked with young players on their base running and bunting skills.

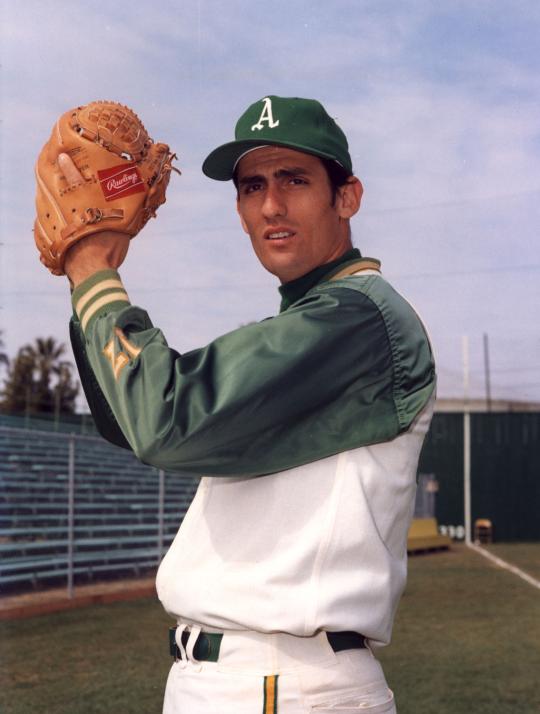

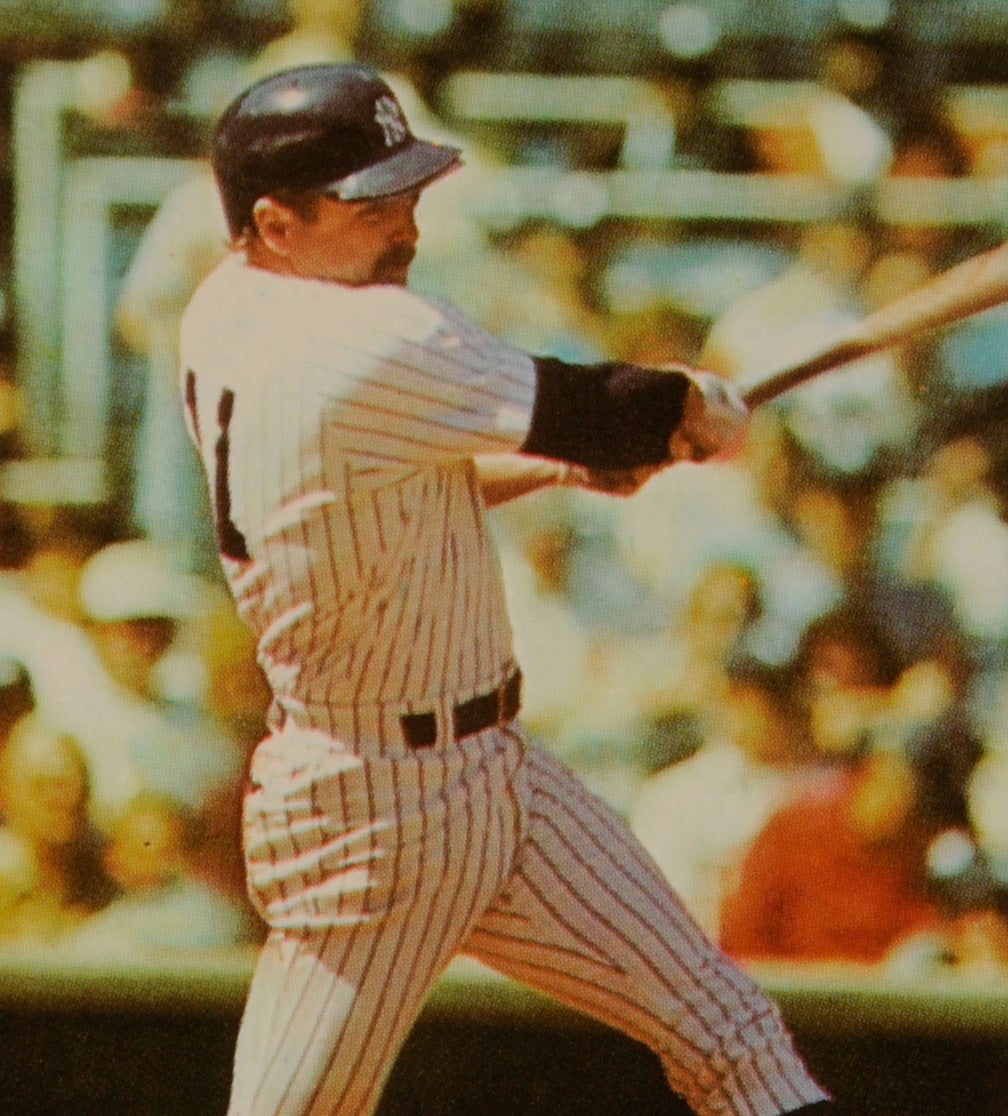

Billy Martin and Bert Campaneris crossed paths during the 1972 American League Championship Series when Campaneris was suspended for throwing a bat at Martin’s pitcher, Lerrin LaGrow. But Martin learned to respect Campaneris later in the shortstop’s career. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

He later worked in the systems of Houston and San Francisco before retiring, but has remained an active member of the MLB Players Alumni Association.

A number of years ago, several staff members here at the Hall of Fame were brought into the reading room at the Hall’s Library. We were told that we would meet several former major leaguers who were visiting the Hall. The group included Vernon Law, Tracy Stallard, Billy North – and North’s old Oakland teammate, Campaneris. Amazingly, Campaneris seemed so fit that he appeared to weigh less than when he topped the scales at 155 pounds in the early 1980s. If it was possible, Campaneris appeared to be in even better condition in retirement than he had been as a player.

Thankfully, the perception of Campy’s character has also improved since that fall day in 1972, when he did something so out of character. No one talks much about the LaGrow incident anymore; most of the conversation has to do with how important Bert Campaneris was to the Oakland dynasty of the early 1970s.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

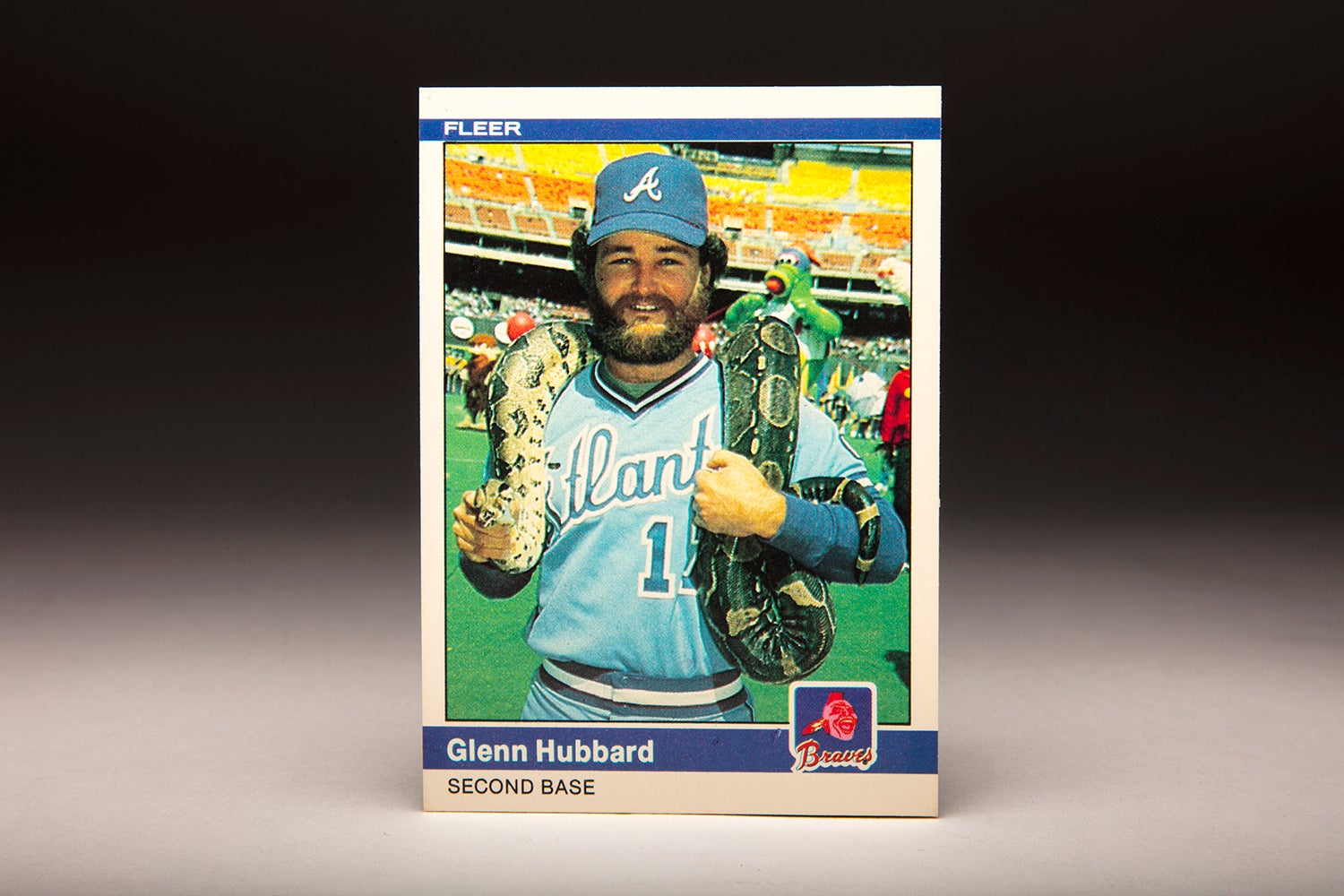

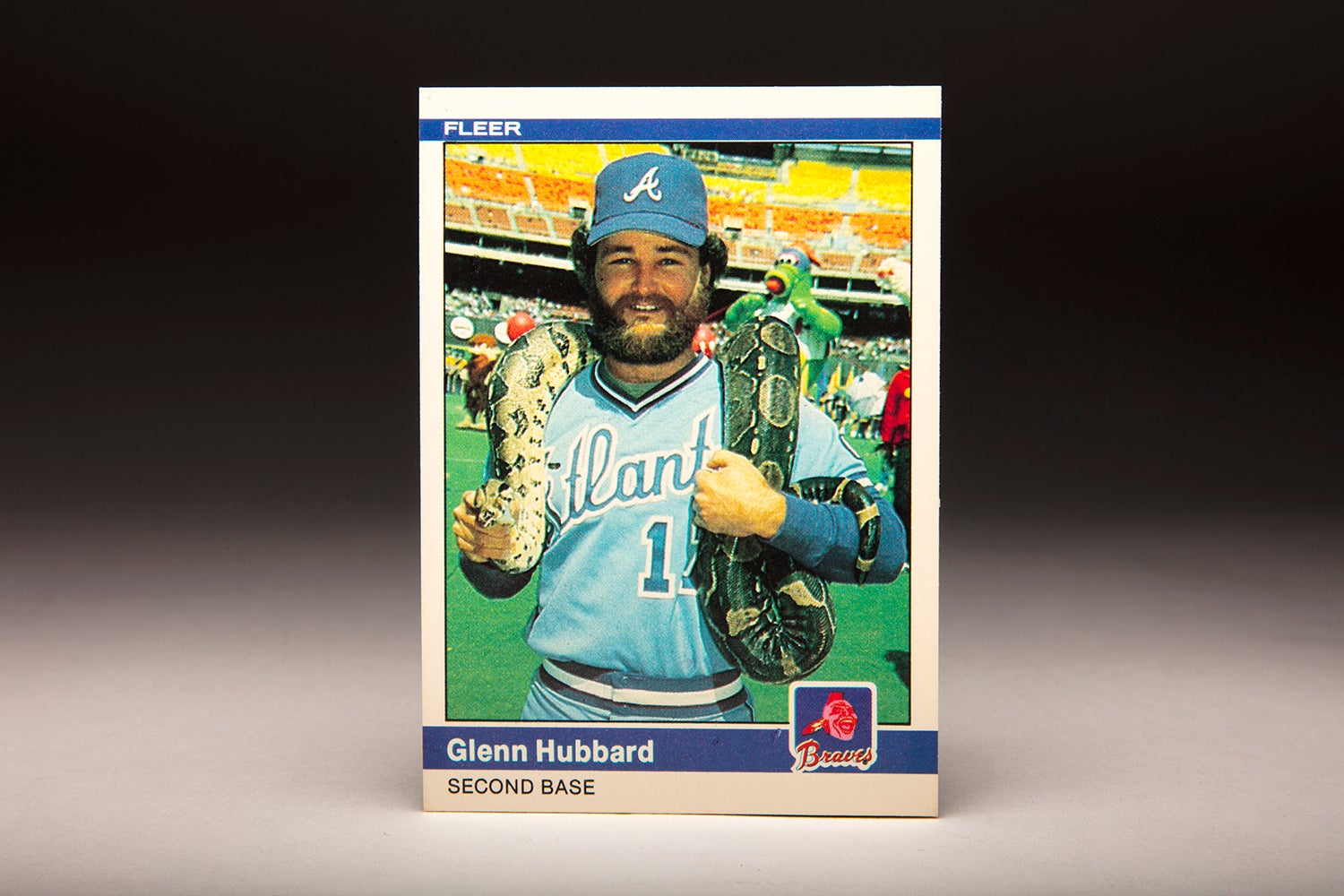

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

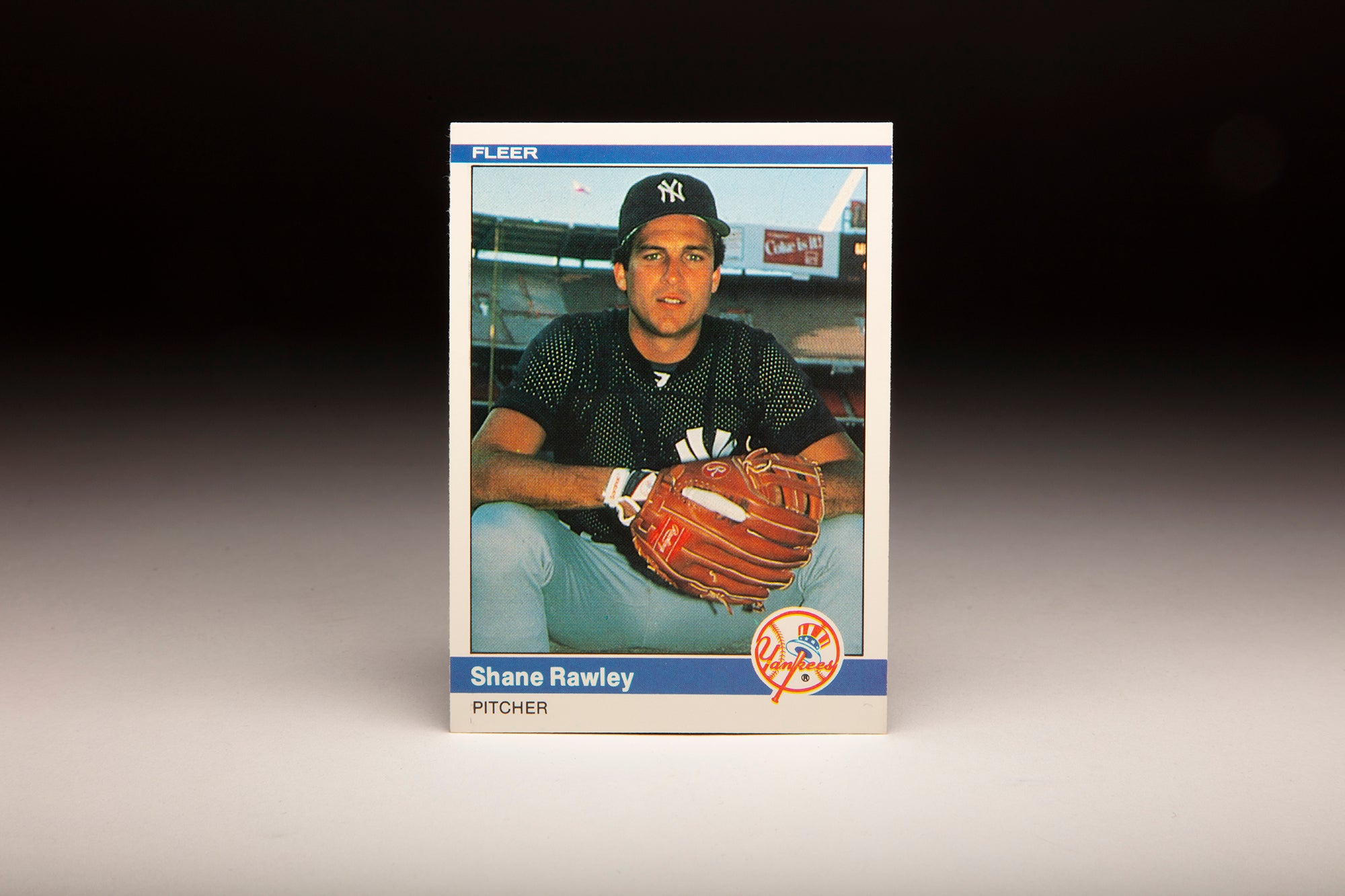

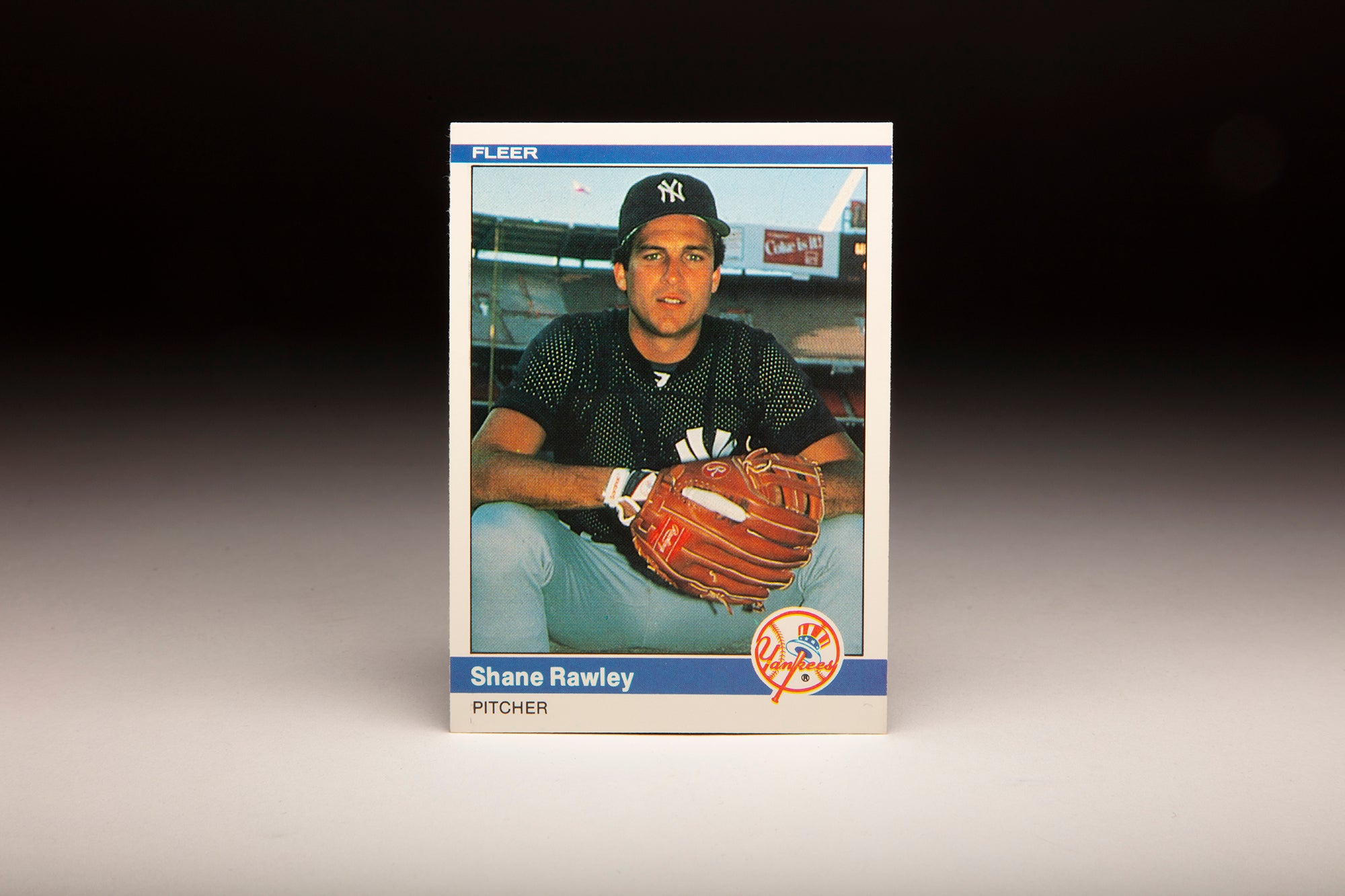

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Shane Rawley

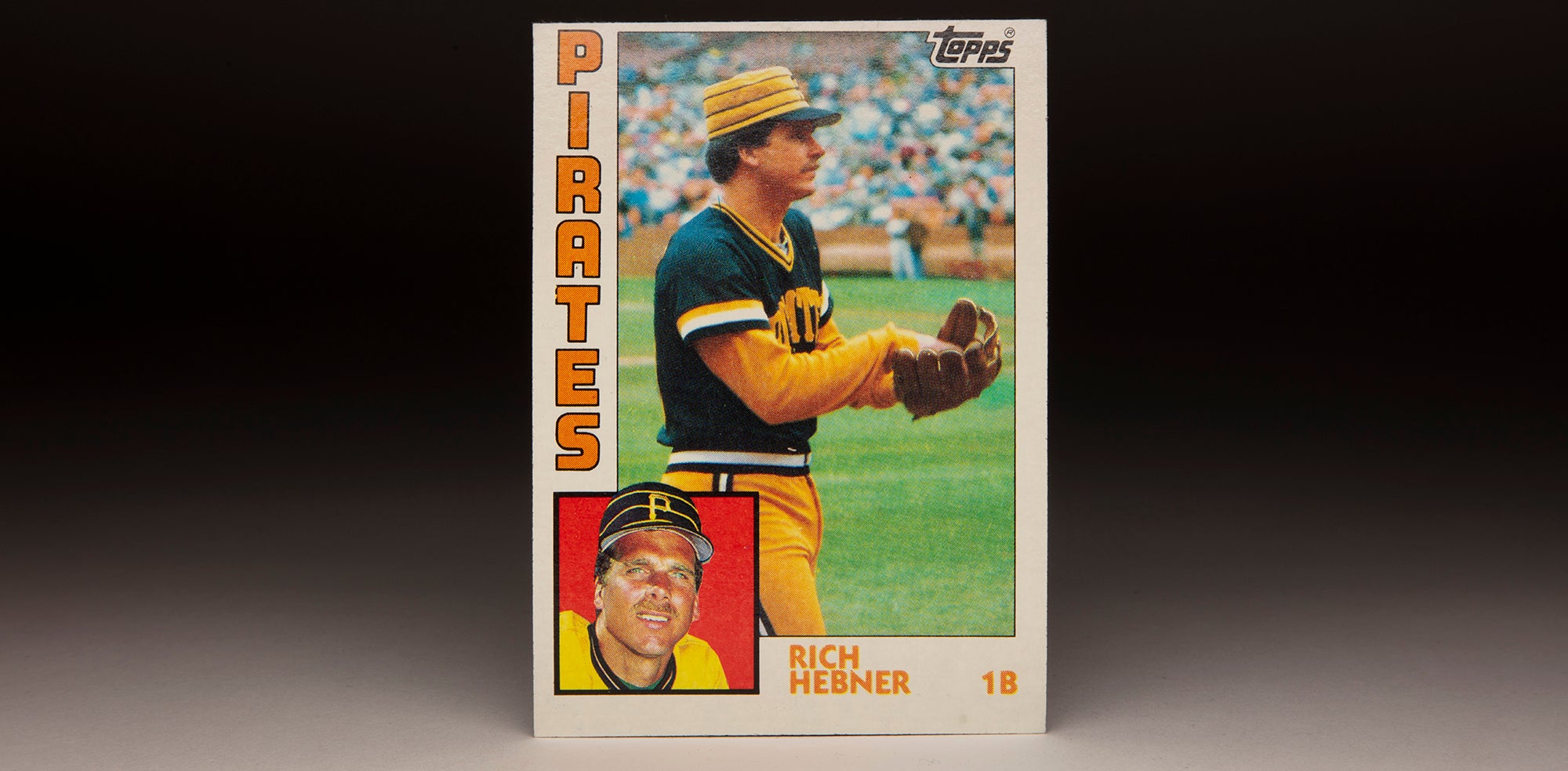

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Richie Hebner

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Shane Rawley